Spanish American wars of independence facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish American wars of independence |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Decolonization of the Americas | |||||||||

|

Decisive events of the war: Congress of Chilpancingo (1813) (top); Congress of Cúcuta (1821) (bottom left); Crossing of the Andes (1817) (bottom right); map of the Spanish nation according to the Cortes de Cádiz (1810) at the beginning of the war (below).

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Participants | |||||||||

|

Others:

|

Others:

|

||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

Royalist forces:

|

Main Patriot forces:

|

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Unknown Spain: 30,000 soldiers (total deployment) |

Unknown 6500 soldiers of British Legions |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown Most of 30,000 Spanish soldiers of expeditionary forces dead from all causes |

Unknown Most of 6500 soldiers of British legions killed or missing in action |

||||||||

| 600,000 military and civilian dead on both sides | |||||||||

The Spanish American wars of independence were a series of conflicts in Spanish America. They took place from 1808 to 1833. The main goal was to gain political freedom from Spain. These wars started when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Spain. This invasion caused a big struggle for power. People in Spanish America wanted to rule themselves. Some wanted a single monarchy, while others wanted republics.

In 1808, Napoleon captured the Spanish royal family. This event sparked ideas of freedom across the Spanish Empire. Violent conflicts began in 1809. Short-lived local governments, called juntas, formed in cities like Chuquisaca and La Paz. They opposed the main Spanish government. By 1810, many new juntas appeared in the Americas. This happened after the main Spanish government fell to the French.

At first, most people in Spanish America did not want full independence. They supported the Spanish government fighting Napoleon. They saw the new local governments as a way to protect their region. They wanted to keep their freedom from French control. While some thought independence was needed, it wasn't the first goal for most.

By late 1810, Ferdinand VII of Spain was recognized as king. But he was under the power of the people. This led to conflict between Royalists and Patriots. Royalists wanted the empire to stay united. Patriots wanted independence. In 1814, Napoleon was defeated. King Ferdinand VII returned to power. He brought back absolute rule. He stopped liberal ideas in Spain. But he could not stop the revolutionaries in Spanish America. They formed their own congresses.

Spain's navy was weak after the war with Napoleon. It could not fully support its forces in America. In 1820, the Spanish army revolted against the king. This revolt helped the Patriots in America. Over the next ten years, Patriot armies won many battles. They gained independence for their countries. Spain still did not want to give up its colonies. But political problems in Spain made many Spanish Americans push for full independence.

These wars were fought in different ways. They included both small-scale fights and large battles. They started as local civil wars. Then they grew into bigger conflicts for independence. New countries formed with borders based on old colonial areas. Cuba and Puerto Rico remained Spanish until 1898.

The wars ended the Spanish Monarchy in America. New independent countries were created. Slavery was not immediately ended in most places. But the new republics removed the old system of racial classes. They also ended the Inquisition and noble titles. People of Spanish descent born in America (Criollos) and mixed-race people (Mestizos) took over most government roles. They replaced Spanish-born officials. Criollos stayed at the top of society. Slavery eventually ended in all new nations.

These events were connected to other independence movements. These included Haiti and Brazil. Napoleon's invasion of Spain and Portugal started all these changes. The ideas of the Age of Enlightenment also played a big part. These ideas influenced revolutions in the United States and France.

Contents

- How the Wars Started

- New Governments in Spain and America (1808–1810)

- History of the Wars

- Effects of Independence

- Foreign Support

- Overview of Conflicts

- Images for kids

- See also

How the Wars Started

Independence was not always the planned outcome. Many historians say there was little interest in full independence at first. It's easy to think that people who were unhappy wanted a revolution. But independence only happened later. People then looked for reasons why it came about. These wars were mainly led by people of European descent against European empires.

Changes by the Spanish Crown

Several things caused the independence movements. First, Spain tried to control its overseas empire more tightly. This happened through the Bourbon Reforms in the mid-1700s. These changes affected how Spanish Americans related to the Spanish Crown. The empire's lands were called "colonies" instead of "kingdoms." This made them seem less important.

Spain also started sending officials from Spain to rule the colonies. This meant that local Spanish Americans, called Criollos, lost their chances to hold important jobs. This made many Criollos unhappy. They felt their hopes were blocked by the Crown's new rules.

The Spanish Crown also tried to reduce the power of the Catholic Church. They had already expelled the Jesuits in 1767. Many Criollo Jesuits had to leave their homes forever. By limiting the Church's power, the Crown wanted more control. The Church had a lot of influence in colonial Latin America. Priests often advised people and helped with legal matters. The Crown wanted to take this direct influence for itself.

Later, the Crown tried to reduce the special rights of the clergy. They wanted to limit the Church's power to spiritual matters. This weakened the power of local priests. These priests were often seen as representatives of the king. By attacking the Church, the Crown weakened its own authority.

The Crown also wanted to control the Church's money. The Church was a very rich organization. It owned a lot of land. The Crown wanted this land for its economic value. Taking land from the Church also helped reduce its influence.

In 1804, Spain faced a money crisis. The Crown tried to collect debts owed to the Church. These debts were mainly mortgages on large estates owned by rich families. This move threatened both the Church's wealth and the rich families. Many families faced bankruptcy. The Crown also tried to take money that families had set aside to support priests. Many lower clergy depended on these funds. In Mexico, some priests, like Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morelos, joined the fight for independence.

These changes had mixed results. In some areas, like Cuba and Mexico, they helped the economy. They also made the government work better. But in other areas, these changes caused problems. They led to revolts, like the Revolt of the Comuneros in New Granada. The Rebellion of Túpac Amaru II in Peru was another example.

Losing high offices and the revolts were direct causes of the wars. Many wealthy Criollos were hurt by the reforms. They used their power to resist the Spanish changes. They were unhappy with the economic impact. But they also worried about radical changes from the lower classes. They preferred slow changes through the Spanish system. But when this didn't happen, people became more radical. This pushed them towards independence.

Military Changes

Spain's wars in the late 1700s showed it was hard to support its colonies. This led to more local people paying for defense. More local people also joined the militias. This went against the idea of a strong, central monarchy. Spain also made promises to strengthen defenses. For example, in Chiloé Archipelago, indigenous people were promised freedom if they helped defend new forts. Local defense groups eventually weakened Spain's power. This helped the independence movement grow.

New Ideas from the Enlightenment

Ideas from the Age of Enlightenment also spread. These ideas encouraged social and economic changes. They spread throughout Spanish America. Ideas about free trade and economics were discussed. These ideas influenced the new governments and constitutions. Many of these were written during the wars.

New Governments in Spain and America (1808–1810)

Fall of the Spanish Royal Family

The French invasion of Spain started a long period of trouble. This lasted until 1823. Napoleon captured the Spanish kings. This caused a big crisis in Spain and Spanish America. Most people rejected Napoleon's plan to make his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, king. But there was no clear leader.

Spanish provinces formed local governments called juntas. But this caused more confusion. There was no central power. Most juntas did not recognize each other. The Junta of Seville claimed power over the overseas empire. This was because Seville had been the main port for trade.

This problem was solved by creating a main government. It was called the "Supreme Central and Governmental Junta of Spain and the Indies". This happened on September 25, 1808. Spanish kingdoms sent two representatives. Overseas kingdoms sent one. These overseas kingdoms included Mexico, Peru, New Granada, and Buenos Aires. Also Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guatemala, Chile, Venezuela, and the Philippines.

This plan was criticized because Spanish America had less representation. But by early 1809, regional capitals elected representatives. Some big cities like Quito and Chuquisaca felt left out. They saw themselves as important kingdoms. This led to them forming their own juntas in 1809. But these were quickly stopped.

Spanish Political Changes

The Supreme Central Junta dissolved in January 1810. This happened after the Spanish forces lost battles. French forces took over southern Spain. The Supreme Junta had to flee to the city of Cádiz.

The Supreme Junta replaced itself with a smaller group called the Regency. This group then called for a special meeting. It was called the "extraordinary and general Cortes of the Spanish Nation." This meeting was held in Cádiz. The plan for electing members was fairer. It gave more time to decide which overseas areas counted as provinces. The Cortes of Cádiz was the first national assembly to claim power in Spain. It ended the old system of separate kingdoms. It met on September 24, 1810. Its members represented the entire Spanish Empire.

History of the Wars

Military Actions

The fighting was very harsh. But both sides often recruited soldiers from the same groups. Socially, the Royalists and Patriots had different meanings for different people. In Europe, Spain forced people to join the army. This led to many rebellions. Independent states used privateers, mercenaries, and adventurers. These fighters were loyal if they were paid.

In America, both sides recruited Native Americans and mixed-race people. They promised social improvements to these groups. Even African slaves were recruited by both sides. Captured soldiers often joined the enemy army. Wealthy Criollos supported either side based on their business interests. The Church was also divided. Lower clergy often joined the rebels. Higher clergy usually supported the political power.

Early Civil Wars (1810–1814)

The creation of juntas in Spanish America led to fighting. This lasted for about 15 years. Political divisions appeared. These often caused military conflicts. The juntas challenged the authority of royal officials. Royal officials were split too. Some were liberals who supported the Cortes. Others were conservatives who wanted no changes.

The juntas claimed to act for the captured King Ferdinand VII. But their creation allowed people who wanted full independence to speak out. These people called themselves Patriots.

Few areas declared independence right after 1810. Venezuela, New Granada, and Paraguay did so in 1811. Some historians say Patriot leaders pretended loyalty to the king. This was to prepare people for the big change of independence. Even areas like Río de la Plata and Chile, which were mostly free, waited years to declare independence. They did so in 1816 and 1818. Many regions had continuous civil wars into the 1820s.

In Mexico, the junta movement was stopped early. But a rebellion started under Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. Hidalgo was captured and executed in 1811. But the resistance continued. They declared independence from Spain in 1813. In Central America, attempts to form juntas were also stopped. But with less violence. The Caribbean islands and the Philippines remained peaceful. Any plots for juntas were quickly reported.

City Rivalries and Conflicts

Major cities and local rivalries played a big role. When the central Spanish power disappeared, many regions broke apart. It was unclear what new political groups would replace the empire. There were no new national identities. People still felt they were Spaniards.

The first juntas in 1810 appealed to being Spanish. This was against the French threat. Then, they appealed to a general American identity. This was against Spain, which was controlled by the French. Finally, they appealed to loyalty to their city or province. This was called the patria.

Often, juntas wanted their province to be independent from the old capital. They also wanted to be free from Spain. Armed conflicts broke out between provinces. They fought over which cities should be in charge. This was very clear in South America. Rivalries also made some regions choose the opposite side. Peru stayed loyal to Spain. This was partly because of its rivalry with Río de la Plata. Peru had lost control of Upper Peru to Río de la Plata in 1776. The juntas in Río de la Plata allowed Peru to regain control of Upper Peru during the wars.

Social and Racial Tensions

Social and racial tensions also affected the fighting. Rural areas fought against cities. People's complaints against authorities found an outlet in the conflict. This happened with Hidalgo's peasant revolt in Mexico. It was fueled by bad harvests as much as by the war in Spain. Hidalgo first tried to form a junta with city people. But after his plot was found, he turned to rural people. Their interests soon became more important.

A similar tension existed in Venezuela. José Tomás Boves, a Spanish immigrant, formed a strong royalist army. He used mixed-race people and plains people (Llaneros). He attacked the white landowners. Boves and his followers often ignored Spanish officials. They cared more about their own power than restoring the king.

In Upper Peru, small rebel groups called republiquetas kept the idea of independence alive. They allied with poor rural people and native groups. But they could never take the big cities.

Fights between Spaniards and Spanish Americans became more violent. This was often about class issues. Patriot leaders also used this tension to create nationalism. Hidalgo's forces killed many Criollos and Peninsulares in Guanajuato. In Venezuela, Simón Bolívar started a "war to the death." Royalist Spanish Americans were spared. But even neutral Spaniards were killed. This was to create a divide between the groups. This policy led to a violent royalist reaction under Boves.

Often, being a Royalist or Patriot was just a banner. People used it to organize their grievances. The political reasons could be dropped quickly. The Venezuelan Llaneros switched to the Patriot side after 1815. This happened when the elites became Royalist. In Mexico, the royal army eventually brought about independence.

King's War Against Independence (1814–1820)

At first, Spain focused on keeping Cuba and Mexico. But in 1814, King Ferdinand VII returned. The war strategy changed. Spain sent its main military effort to South America. By 1815, royalists and pro-independence forces had established control in different areas. The war became a stalemate. In royalist areas, those seeking independence fought as small guerrilla groups.

In Mexico, Guadalupe Victoria and Vicente Guerrero led the main guerrilla groups. In northern South America, Patriots from New Granada and Venezuela fought. Leaders like Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Paula Santander led campaigns. They often got help from Curaçao and Haiti. In Upper Peru, guerrilla groups controlled rural areas.

Ferdinand VII Returns to Power

In March 1814, Ferdinand VII became king of Spain again. This was a big change. Most political changes had been made in his name. Before entering Spain, Ferdinand promised to uphold the Spanish Constitution. But once in Spain, he saw he had strong support from conservatives. So, on May 4, he rejected the Constitution. He ordered the arrest of liberal leaders. Ferdinand said the Constitution was made without his consent. He brought back old laws and institutions. He promised a new Cortes, but never held one.

News of these events reached Spanish America over several months. Ferdinand's actions broke ties with autonomous governments. These governments had not yet declared full independence. It also broke ties with Spanish liberals. They wanted a government that included overseas lands. Many in Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, Quito, Peru, and Chile saw this as an alternative to independence.

But the news of the old system returning did not cause new juntas. Only Cuzco formed one, demanding the Spanish Constitution. Most Spanish Americans waited to see what would happen. In some areas, governors kept elected local councils for years. This was to avoid conflict. Liberals on both sides of the Atlantic still tried to bring back a constitutional monarchy. They succeeded in 1820.

Spanish Americans in royalist areas who wanted independence had already joined guerrilla groups. But Ferdinand's actions pushed areas outside royal control towards full independence. These governments had started as juntas in 1810. Even moderates who wanted to reconcile with Spain now saw the need to separate. They needed to protect the changes they had made.

Royalist Military Strength

During this time, royalist forces advanced into New Granada and Chile. They controlled New Granada from 1815 to 1819. They controlled Chile from 1814 to 1817. Spain sent its largest force ever to the New World in 1815. It had 10,500 troops and nearly 60 ships. This force helped retake New Granada. But its soldiers were spread out. Many died from tropical diseases. This reduced their impact.

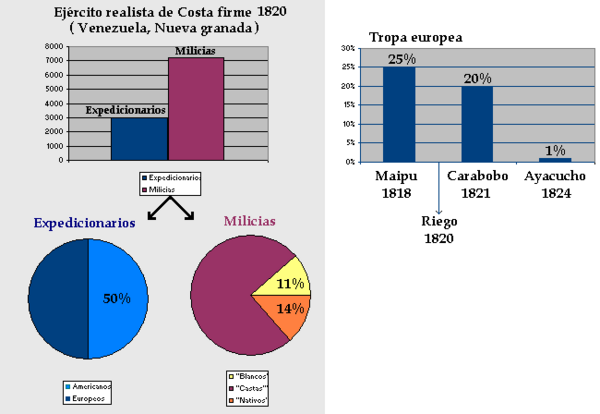

Most royalist forces were not from Spain. They were Spanish Americans. Europeans made up only about one-tenth of royalist armies. They were about half of the expeditionary units. As European soldiers died, Spanish Americans replaced them. So, over time, more and more Spanish Americans were in these units. For example, in 1820, Pablo Morillo, a Spanish commander, had only 2,000 European soldiers. This was half of his expeditionary force. In the Battle of Maipú, only a quarter of royalist forces were European. In the Battle of Carabobo, about a fifth. In the Battle of Ayacucho, less than 1% were European.

American militias reflected the local population's racial makeup. In 1820, the royalist army in Venezuela had 843 white, 5,378 mixed-race, and 980 indigenous soldiers.

Patriot Advances

Towards the end of this period, Patriots made two big advances. In the south, José de San Martín was a Spanish army veteran. He had fought in the Peninsular War. He became governor of Cuyo Province. He started organizing an army in 1814. He planned to invade Chile. This was a new strategy. Three earlier campaigns in Upper Peru had failed.

San Martín's army became the Army of the Andes. It got important support in 1816. Juan Martín de Pueyrredón became the leader of the United Provinces. In January 1817, San Martín was ready to attack royalists in Chile. He led his army over the Andes mountains. This surprised the royalists. By February 10, San Martín controlled northern and central Chile. A year later, after a harsh war, he controlled the south. With help from a fleet led by Thomas Cochrane, Chile was secured. Independence was declared that year. San Martín then planned to invade Peru. This began in 1820.

In northern South America, Simón Bolívar had failed to take Caracas several times. In 1819, he planned to cross the Andes. He wanted to free New Granada from the royalists. Like San Martín, Bolívar built an army to invade a neighboring country. He worked with exiles from that region. He also lacked approval from the Venezuelan congress.

Unlike San Martín, Bolívar did not have a professional army. His army was a mix of guerrillas, exiles, and British recruits. From June to July 1819, Bolívar led his army across flooded plains and cold mountains. They suffered heavy losses. A quarter of the British Legion died. Many of his soldiers were not ready for the high altitudes. But the risk paid off. By August, Bolívar controlled Bogotá and its treasury. He gained support in New Granada. People still resented the harsh royalist rule.

Francisco de Paula Santander continued the "war to the death" policy. He executed 38 royalist officers who had surrendered. With New Granada's resources, Bolívar became the main Patriot leader. He united the two regions into a new state called Gran Colombia.

Independence Achieved (1820–1825)

Spain prepared a second large force in 1819. It was meant to fight the Patriots in South America. But this force never left Spain. Instead, it led to liberals restoring a constitutional government. On January 1, 1820, Rafael del Riego led a rebellion among the troops. He demanded the return of the 1812 Constitution. His troops marched through cities. But locals were mostly indifferent. However, an uprising happened in Galicia, Spain. It quickly spread. On March 7, the royal palace in Madrid was surrounded. On March 10, King Ferdinand VII agreed to restore the Constitution.

Riego's Revolt had two big effects in America. First, the needed reinforcements never arrived. Second, as royalists became weaker, many units joined the Patriots. Politically, the new liberal government changed how Spain dealt with rebels. It wrongly thought rebels were fighting for Spanish liberalism. It believed the Spanish Constitution could unite both sides. The government held elections in overseas provinces. It also told military commanders to negotiate with rebels. It promised they could join the new government.

Mexico and Central America

The Spanish Constitution of 1812 became the basis for independence in Mexico and Central America. In both regions, a mix of conservative and liberal royalist leaders created new states. The 1812 Constitution tried to bring back old Spanish policies. These policies treated colonies as equal kingdoms. They also allowed for changes and more rights.

The return of the Constitution was welcomed in Mexico and Central America. Elections were held. Local governments formed. Representatives were sent to the Cortes. The 1812 Constitution could have allowed slow social change. It could have avoided radical uprisings. But liberals feared the new government wouldn't last. Conservatives and the Church worried about more reforms. Since the Cortes was in Spain, political power stayed there. This frustrated many Spanish Americans. They couldn't control policies affecting them. This instability led to an alliance.

This alliance formed in late 1820. It was led by Agustín de Iturbide. He was a colonel in the royal army. He was tasked with destroying rebel forces led by Vicente Guerrero. In January 1821, Iturbide was chosen by officials in Mexico. He was sent to Guerrero. He started "peace" talks. He suggested they unite to create an independent Mexico. Iturbide was later captured and executed.

Iturbide's simple ideas became the Plan of Iguala. This plan called for Mexico's independence. It wanted Ferdinand VII or another Bourbon as emperor. It kept the Catholic Church as the official religion. It protected the Church's special rights. It also said all New Spaniards were equal. This included immigrants and native-born people. Many of these laws were later changed in Mexico.

The next month, Guadalupe Victoria, another rebel leader, joined the alliance. On March 1, Iturbide was made head of the new Army of the Three Guarantees. The new Spanish official, Juan O'Donojú, arrived in Veracruz on July 1, 1821. But royalists held almost the entire country. Only Veracruz, Mexico City, and Acapulco remained. O'Donojú had left Spain when the Cortes was considering more freedom for colonies. So, he offered to negotiate with Iturbide.

The Treaty of Córdoba was signed on August 24. It kept all existing laws, including the 1812 Constitution. This was until a new Mexican constitution could be written. O'Donojú joined the temporary government. Both the Spanish Cortes and Ferdinand VII rejected the treaty. Mexico's final break from Spain came on May 19, 1822. The Mexican Congress made Iturbide emperor. Spain recognized Mexico's independence in 1836.

Central America gained independence with Mexico. On September 15, 1821, an Act of Independence of Central America was signed. It declared Central America (Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica) free from Spain. Local leaders supported the Plan of Iguala. They joined Central America with the Mexican Empire in January 1822. A year later, after Iturbide's fall, the region peacefully left Mexico. This happened on July 1, 1823. They formed the Federal Republic of Central America. This new state lasted 17 years. The provinces then broke apart by 1840.

South America's Fight for Freedom

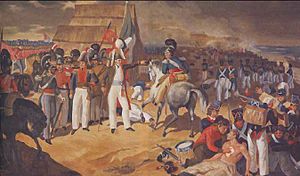

In South America, independence was driven by Patriot fighters. They had held out for years. José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar led a huge effort. They moved from the south and north of South America. They freed most Spanish American nations. After securing Chile's independence in 1818, San Martín focused on building a navy. He wanted to challenge Spain's control of the Pacific. He aimed to reach Lima, a royalist stronghold.

By mid-1820, San Martín had a fleet of 8 warships and 16 transport ships. It was led by Admiral Cochrane. The fleet sailed from Valparaíso to Paracas in southern Peru. On September 7, the army landed and took Pisco. San Martín then avoided direct fighting. He hoped his presence would start a Peruvian revolt. He believed true liberation needed local support.

San Martín negotiated with Viceroy Joaquín de la Pezuela. Pezuela was ordered to negotiate based on the 1812 Constitution. He wanted to keep the Spanish Monarchy united. But these talks failed. Independence and unity could not be combined. So, the army sailed to Huacho in northern Peru. Over the next months, they won land and naval battles. San Martín learned that Guayaquil (in Ecuador) had declared independence on October 9.

Bolívar learned about the collapse of the Spanish expedition. He spent 1820 preparing a campaign in Venezuela. Spain's new policy helped Bolívar. Morillo, the Spanish commander, resigned and returned to Spain. Bolívar rejected Spain's offer to rejoin under the Constitution. But both sides agreed to a six-month truce. They also agreed to rules of engagement.

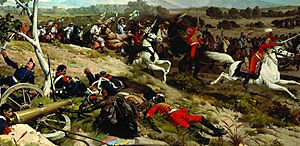

The truce did not last. It was clear the royalist cause was weak. Many royalist soldiers deserted or joined the Patriots. On January 28, 1821, Maracaibo declared itself an independent republic. It joined Gran Colombia. Miguel de la Torre, the new Spanish commander, saw this as a truce violation. Both sides prepared for war. Venezuela's fate was sealed when Bolívar returned in April. He led an army of 7,000 from New Granada. At the Battle of Carabobo on June 24, Gran Colombian forces defeated the royalists. This secured Venezuela's independence. Bolívar could now focus on Gran Colombia's claims in southern New Granada and Quito.

In Peru, Viceroy Pezuela was removed in a coup on January 29, 1821. José de la Serna took his place. San Martín moved his army closer to Lima. He again negotiated. He offered to create an independent monarchy. But La Serna insisted on Spanish unity. So, talks failed. By July, La Serna felt his hold on Lima was weak. On July 8, the royal army left Lima. They moved to the highlands, with Cuzco as the new capital. On July 12, San Martín entered Lima. He was declared "Protector of the Country" on July 28. This allowed him to rule the new state.

To ensure Quito joined Gran Colombia, Bolívar sent aid. He sent supplies and an army under Antonio José de Sucre to Guayaquil in February 1821. For a year, Sucre could not take Quito. In November, both sides signed a 90-day truce. The next year, on May 24, 1822, at the Battle of Pichincha, Sucre's forces conquered Quito. Gran Colombia's control was secure.

The next year, a Peruvian Patriot army was defeated. San Martín met with Simón Bolívar in Guayaquil on July 26 and 27. San Martín then decided to retire. For the next two years, two Patriot armies were destroyed. They tried to enter the royalist stronghold in Peru and Upper Peru. A year later, a Peruvian congress made Bolívar the head of Patriot forces.

A conflict between La Serna and General Pedro Antonio Olañeta weakened the royalists. La Serna lost half of his best army by early 1824. This gave the Patriots a chance.

Under Bolívar and Sucre, the combined army destroyed a royalist army. This happened at the Battle of Ayacucho on December 9, 1824. La Serna's army was larger but had mostly new recruits. The only major royalist area left was Upper Peru. After Ayacucho, royalist troops in Upper Peru surrendered. Their commander, Olañeta, died on April 2, 1825.

Bolívar wanted Upper Peru to stay united with Peru. But Upper Peruvian leaders wanted independence. Many were former royalists. They gathered in a congress. Sucre supported their independence. Sucre declared Upper Peru's independence on August 6. The city was named Sucre. This ended the main wars of independence.

As independence became certain, new states gained international recognition. In 1822, the United States recognized Chile, the United Provinces of Río de la Plata, Peru, Gran Colombia, and Mexico. Britain waited until 1825, after Ayacucho. It recognized Mexico, Gran Colombia, and Río de la Plata. Both nations recognized more Spanish American states later.

Last Royalist Strongholds (1825–1833)

Spanish coastal forts in Veracruz, Callao, and Chiloé resisted until 1825 and 1826. In the next decade, royalist guerrillas still operated. Spain tried a few times to retake parts of the mainland. In 1827, Colonel José Arizabalo started a guerrilla war in Venezuela. Brigadier Isidro Barradas led the last attempt to reconquer Mexico in 1829. The Pincheira brothers were royalist outlaws in Patagonia until 1832. But these efforts did not change the new political situation.

The Holy Alliance became less important after 1825. The Bourbon family fell in France in 1830. This removed Ferdinand VII's main support in Europe. Spain finally gave up all plans of military reconquest after the king's death in 1833. In 1836, Spain officially gave up control over all of continental America. Over the 19th century, Spain recognized each new state. Only Cuba and Puerto Rico remained Spanish until the Spanish–American War in 1898.

Effects of Independence

Economy

The wars lasted for about 15 years. They greatly weakened Spanish American economies. They also damaged political systems. This slowed down economic growth for most of the 1800s. It also led to lasting instability. Independence broke the trade system of the Spanish Empire. After independence, trade between the new nations was less than before.

The small populations of most new nations did not encourage old trade patterns. Also, the protection from European competition ended. Spain's monopoly had protected local industries. Now, foreign imports beat out local production. This hurt Native communities. They had specialized in making products for city markets. Cities that relied on sea trade, like Valdivia, faced hard times.

New states in Latin America, especially Mexico, sought foreign money. This often came as loans. These loans further hurt economies already damaged by conflict. This money was not enough for recovery. It pushed these new states further into debt. When the new nations joined the world economy, Europe and the US were recovering. They aggressively sought new markets. Spanish America could only export raw materials. It had to buy finished products.

Society

Independence from Spain needed all social classes to work together. But each group had different ideas for the new society. This made it hard for societies to unite. It led to more conflict when forming new states. The wealthy Criollo class had power. They controlled how states developed. They made sure they stayed in power.

The new Latin American states met some demands of other groups. This was to ensure stability. But they also made sure Criollo elites kept their power. The political debate was between liberals and conservatives. Conservatives wanted to keep traditional social structures. They wanted stability. Liberals wanted a more dynamic society and economy. They wanted to end racial distinctions. They also wanted to free property from old rules. To change society, liberals often made policies that Native communities disliked. Native communities had benefited from special protections under Spanish law.

Independence did start the end of slavery. Many slaves gained freedom by joining Patriot armies. In areas where slavery was not common (Mexico, Central America, Chile), it ended quickly. In areas where slavery was important (Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Argentina), it ended gradually. This happened over the next 30 years. Laws were passed to free children born to slaves. Programs for paid emancipation were also created. By the early 1850s, slavery was abolished in independent Spanish America.

Role of Women

Women were not just observers during the wars. Many women took sides. They joined independence movements at different levels. Women acted as caring relatives. They were mothers, sisters, wives, or daughters of fighting men. Women created political groups. They organized meetings to donate food and supplies to soldiers.

Some women supported the wars as spies, informants, and even fighters. Manuela Sáenz was a close partner of Simón Bolívar. She was his spy and confidante. She saved his life twice. She nursed wounded soldiers. Some historians believe she fought in battles. Sáenz followed Bolívar and his army. She became known as the "mother of feminism." Bolívar supported women's rights. He made Sáenz a Colonel in the Colombian Army. This was controversial because there were no women in the army then.

Another important woman was Juana Azurduy de Padilla. She was a mixed-race woman. She fought for independence in the Río de la Plata region. She was later promoted to general.

Women were not expected to be soldiers. But many women were on battlefields. They helped rescue and nurse soldiers. Some fought alongside their families. Most women had supportive roles. They raised money and cared for the sick. For women, revolution meant something different. They saw it as a way to gain equal rights, like voting. They wanted to overcome being seen as less important than men.

Women were often seen as victims during the wars. They were forced to sacrifice for the cause. The idea of womanhood meant women had to sacrifice what was needed. A mother might sacrifice her son. A young woman might sacrifice marriage due to the loss of many young men. This view meant women contributed in supportive roles. Combat and politics were left to men.

Government and Politics

Independence did not always lead to stable governments. Only a few countries achieved this. First, the new nations did not have clear identities. The process of creating identities was just beginning. This happened through newspapers and new national symbols. Countries got new names like "Mexico," "Colombia," "Ecuador," "Bolivia," and "Argentina." This broke with the past.

Borders were not firm. The struggle between federalism and centralism continued for the rest of the century. Two large states from the wars, Gran Colombia and the Federal Republic of Central America, collapsed after a decade or two. Argentina did not become politically stable until the 1860s.

The wars destroyed the old government system. Institutions like the audiencias (high courts) were removed. Many Spanish officials fled to Spain. The Catholic Church was an important social and political institution. It was weakened at first. Many Spanish bishops left their areas. Their positions were not filled for decades. This was until new bishops could be appointed. Relations between new nations and the Vatican were also restored. As the Church recovered, its power was attacked by liberals.

The wars led to a quick growth of representative government. But for several new nations, the 1800s were marked by military rule. This was because of a lack of strong political institutions. Armies and officers from the independence process wanted rewards. Many armies did not fully disband. They became stable institutions in the early years. These armies and their leaders influenced political development. This led to caudillos. These were strongmen who gained economic, military, and political power.

Foreign Support

United Kingdom

Britain wanted Spanish rule in South America to end. It wanted to access the important markets there. But it also wanted Spain as an ally in Europe. So, Britain secretly supported the revolutionaries. It sent men, money, and supplies to help them fight Spain.

One of the biggest contributions was the British Legions. This was a group of volunteers. They fought under Simón Bolívar. This force had over 6,000 men. Most were veterans of the Napoleonic Wars. Their greatest achievements were at Boyacá (1819), Carabobo (1821), Pichincha (1822), and Ayacucho (1824). These battles secured independence for Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Peru. Bolívar called the Legions "the saviours of my country."

Many British Navy members also volunteered. The most famous was Thomas Cochrane. He reorganized the Chilean navy. Most of his men were British Navy veterans. He captured the Spanish fortress of Valdivia in 1820. In the same year, he captured the Spanish flagship Esmeralda in Callao port. Cochrane helped Chile gain independence. He also helped Peru by blocking ports and transporting troops. He then helped Brazil fight for independence from Portugal.

At their peak in 1819, about 10,000 men from the British Isles served in South America. They fought against Spain. British diplomacy also played a key role. Foreign secretaries like Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh and George Canning wanted Spain's colonies to fall. Castlereagh helped block aid to Spain at European meetings. This stopped Spain from reconquering South America. The British Navy controlled the oceans. This was a decisive factor in the independence struggle.

France

Napoleon Bonaparte wanted to control Spain and Spanish America. His brother, Joseph Bonaparte, was king of Spain from 1808-1813. He never signed any document for Latin American independence. Napoleon did not give up these rights. When he lost the war in Spain, he returned the Spanish crown to Ferdinand VII in 1813. After the Bourbon kings returned, France supported Ferdinand VII in Spain. It helped bring back absolute rule. But France never provided money or fighters for the independence wars.

United States

The United States intervened for two reasons. One was territorial annexation. The other was revolts within Spanish lands.

The Republic of West Florida was a short-lived republic in 1810. It was in western Spanish West Florida. After less than three months, the United States annexed it. It became part of Louisiana. The Republic of East Florida was another republic. It declared itself against Spanish rule. Its rebels wanted to join the United States, but failed. In 1819, the Treaty of Florida was signed. Spain gave all of Florida to the United States.

In 1811, Spain crushed the San Antonio revolt in Texas. This was during the Mexican War of Independence. The remaining rebels asked the United States for help. Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara went to Washington, D.C. He gained support from Augustus Magee. They formed a US volunteer force in Louisiana. This force was called the Northern Republican Army. It was defeated in the bloodiest battle in Texas, the Battle of Medina. Texas then became part of Mexican Independence. Later, Texas gained its own independence and joined the United States.

The United States remained neutral for a while. This policy favored the rebels. Border problems with Spain caused tension. The US had to be careful. It wanted to avoid giving Europe an excuse to intervene. Recognizing the new states in 1822 was also a delicate international move.

Russia

The Spanish navy was very weak after the war with Napoleon. In 1817, Tsar Alexander supported conservative governments. Ferdinand VII asked the Tsar to buy ships. The Tsar agreed to sell some of his own ships. The agreement was made in Madrid. It was kept very secret. The treaty text has not been found.

The fleet was to have 5 warships and 3 frigates. They would be delivered armed and supplied. The Russian fleet arrived in Cadiz in February 1818. The Spanish navy was unhappy. Some supposedly new ships were in bad condition. Between 1820 and 1823, all the warships were scrapped. This failure ended the plan to reconquer Río de la Plata. It led to the Spanish Army uprising in Cadiz in 1820. In 1818, one frigate was captured in the Pacific. This happened after a Spanish troop transport rebelled. It gave away all the keys and routes for the frigate's capture. Only two Russian frigates provided services in the Caribbean. They defended Cuba. But they only made a one-way trip. They were lost or sank when they arrived in Havana.

Portuguese Empire

After a long dispute, Portugal organized an army. It wanted to defend Montevideo against revolutionaries in 1811. It also wanted to annex the disputed territory of Banda Oriental in 1816.

In 1811, the first Portuguese invasion happened. It supported Montevideo, which was under siege. The Portuguese aimed to help Montevideo and the viceroy of Río de la Plata. They were besieged by revolutionary forces. The invasion included clashes with forces led by José Gervasio Artigas. After a brief agreement, the Portuguese did not fully leave the occupied area.

In 1816, the second Portuguese Invasion began. This was a war against Artigas. It took place from 1816 to 1820. It covered Uruguay, Argentine Mesopotamia, and southern Brazil. It resulted in Banda Oriental joining the Portuguese Empire. It was called Cisplatina Province. This annexation broke relations with Spain. Spain prepared an army to retake Montevideo. But this plan ended with the army's rebellion in Cadiz in 1820. Portugal tried to secure its annexation. It was the first country to recognize the independence of Latin American Republics in 1821.

Overview of Conflicts

Wars, Battles, and Revolts

| Mexico and Central America | Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador |

|

Mexico

Central America |

|

| Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia | Chile and Peru |

|

|

Key Leaders for Independence

Key Royalist Leaders

| Mexico, Guatemala, Cuba & Puerto Rico Félix María Calleja del Rey, 1st Count of Calderón | Colombia, Venezuela & Ecuador Pablo Morillo | Argentina, Montevideo & Paraguay Santiago de Liniers, 1st Count of Buenos Aires | Chile, Peru & Bolivia José Fernando de Abascal y Sousa |

|

|

|

|

Images for kids

- Age of Revolution

- British Legions

- List of foreign volunteers

- Insurgent privateer

- Philippine Revolution

- Spanish reconquest of Mexico

- Royalist

- Wars of national liberation

- History of South America

- History of Mexico

- New Spain

- Spanish East Indies

- Decolonization of the Americas

- Timeline of the Spanish American wars of independence

- Timeline of Mexican War of Independence

- Panhispanism

- Argentine War of Independence

See also

In Spanish: Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas para niños

In Spanish: Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas para niños