Chilean War of Independence facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chilean War of Independence |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish American Wars of independence | |||||||

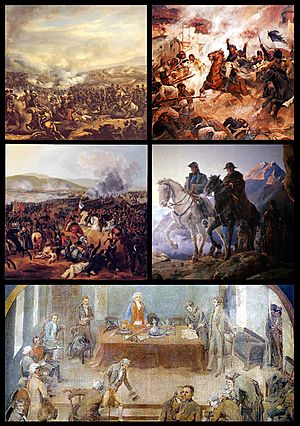

Clockwise from top left: Battle of El Roble, Battle of Rancagua, Crossing of the Andes, First Government Junta, Battle of Maipú. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Mapuche allies of the Patriots |

Mapuche allies of the Royalists |

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

The Chilean War of Independence was a big military and political event. It helped Chile break free from the Spanish Crown. This war ended the time when Spain ruled Chile as a colony. It also started the process of Chile becoming an independent country.

This war was part of many similar fights across Spanish America. These fights began after Napoleon's forces captured King Ferdinand VII of Spain in 1808. In response, local governments called "juntas" were formed in Spanish colonies. The First Government Junta of Chile was one of these.

At first, these juntas just wanted to rule while the King was captured. But soon, some people, called Patriots, wanted complete freedom from Spain. Others, called Royalists, wanted to stay part of the Spanish Empire. This led to a big fight between them.

Historians usually say this war lasted from September 18, 1810, to January 28, 1823. It is divided into three main parts:

- The Patria Vieja (Old Homeland) from 1810 to 1814.

- The Reconquista (Reconquest) from 1814 to 1817.

- The Patria Nueva (New Homeland) from 1817 to 1823.

Even though the main war ended in 1823, the last Spanish forces were defeated in 1826. Chile officially declared its independence on February 12, 1818. Spain finally recognized Chile's independence in 1844.

Contents

How It All Started

In 1808, Chile was a small and not very rich colony of the Spanish Empire. It was governed by Luis Muñoz de Guzmán, who was a good and respected leader. But he suddenly died in February 1808. Spain couldn't name a new governor right away because of big problems in Europe.

In May 1808, news arrived that Napoleon had taken over Spain. He removed King Charles IV and King Ferdinand VII from power. This caused a lot of confusion and anger across the Spanish Empire. In Chile, a military leader named Francisco Antonio García Carrasco became the new governor.

Governor García Carrasco was a tough and sometimes unfair leader. He quickly made the local Chilean leaders, called criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the colonies), unhappy. Most people in Chile were loyal to Spain. But they were divided into groups:

- Absolutists: Wanted to keep things exactly as they were and supported King Ferdinand VII.

- Carlotists: Wanted Charlotte Joaquina, the King's sister, to rule. She was living in Brazil and wanted to take control of Spanish colonies.

- Juntistas: Wanted to create a local government, called a junta, made of important citizens. This junta would rule Chile while the King was captured.

In 1809, Governor García Carrasco was involved in a corruption case. This made people trust him even less. In June 1810, news came that Napoleon's forces had taken over most of Spain. Only the city of Cádiz was still free. The main Spanish government, the Supreme Central Junta, had also been replaced by a new council.

García Carrasco made things worse by arresting important citizens without a fair trial. He suspected them of supporting the idea of a local junta. These unfair actions, along with the news from Spain, made the criollo leaders even more determined to oppose him.

On July 16, 1810, Governor García Carrasco was forced to resign. He was replaced by Mateo de Toro Zambrano. He was a very old man, 82 years old, and was a criollo (born in the colonies), not a "peninsular" (born in Spain).

The juntistas quickly pushed Toro Zambrano to form a local government. After some hesitation, he agreed to hold a special meeting called a Cabildo (city council) in Santiago. This meeting was set for September 18, 1810.

The Old Homeland (Patria Vieja): First Steps to Freedom

The First Government Junta

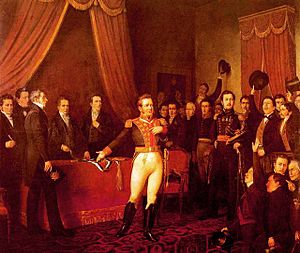

At the Cabildo meeting on September 18, 1810, the juntistas were very organized. They made sure their supporters were there. They shouted, "We want a junta! We want a junta!" Count Toro Zambrano, seeing how strong their support was, agreed. He placed his special staff on the table and said, "Here is the staff, take it and rule."

The new government was called the Government Junta of the Kingdom of Chile, or the First Junta. It had the same powers as a Spanish governor. Their first act was to promise loyalty to King Ferdinand VII. Count Toro Zambrano was chosen as President. But the real power was held by the secretary, Juan Martínez de Rozas.

The Junta quickly made important changes:

- They created a local army to defend Chile.

- They allowed free trade with all countries allied with Spain or neutral.

- They set a special tax on imports, but books, printing presses, and guns were tax-free.

- They called for a National Congress to be elected to represent more people.

Soon, three political groups formed:

- Extremists: Wanted more freedom from Spain and faster changes, almost full independence. Their leader was Juan Martínez de Rozas.

- Moderates: Wanted slow changes. They feared that if the King returned, he would cancel all reforms if they went too far. Their leader was José Miguel Infante.

- Royalists: Did not want any changes and wanted to keep things exactly as they were under Spanish rule.

Elections for the National Congress were planned for 1811. In March 1811, most cities had elected their representatives. But the results were mixed. The Santiago elections were very important for Rozas to keep his power.

On April 1, a Royalist colonel named Tomás de Figueroa started a revolt in Santiago. He thought elections were too much like a popularity contest. The revolt failed, and Figueroa was arrested and executed. This mutiny delayed the elections but also made people's political views stronger.

When the National Congress was finally elected, the Moderates had the most seats. But a small group of Extremists now openly wanted complete independence. The Royal Audiencia of Chile, a main Spanish court, was closed because it was thought to be involved in the mutiny. This event made the idea of full independence much more popular.

José Miguel Carrera's Leadership

Around this time, a young, ambitious soldier named José Miguel Carrera returned to Chile from Spain. He had fought in the wars in Europe. He quickly joined the Extremists who wanted to take power from Martínez de Rozas. After two military takeovers in late 1811, Carrera became the leader of Chile. His brothers, Juan José and Luis, and Bernardo O'Higgins were also important in his government.

In 1812, Carrera's government created a new constitution. It said that no order from outside Chile could be enforced. Anyone trying to do so would be seen as a traitor. Carrera also created Chile's first national symbols, like the flag and shield.

During his rule, the first Chilean newspaper, La Aurora de Chile, was published. It supported independence. Carrera also brought the first American consul to Chile. This helped connect Chile's independence movement with the ideas of freedom from the United States. He also founded important schools and libraries that still exist today.

Spanish Forces Attack

The success of the independence movements in Chile and Argentina worried the Spanish leader in Peru, José Fernando de Abascal. In 1813, he sent a Spanish army by sea to Chile, led by Antonio Pareja. These troops landed in Concepción and were welcomed by Royalist supporters. Pareja tried to capture Santiago, but he failed. Another attack led by Gabino Gaínza also failed.

Carrera's military leadership was not very good. This led to the rise of Bernardo O'Higgins, who became the main leader of the Patriot forces. Carrera eventually resigned. This moment is often seen as the start of the Reconquista period.

After Gaínza's attack, both sides signed the Treaty of Lircay in May 1814. This treaty was supposed to bring peace, but it only gave them a short break. Abascal, the Viceroy of Peru, did not plan to honor the treaty. He sent an even stronger force to Chile, led by Mariano Osorio.

Osorio's army landed and moved towards Chillán, demanding that the Patriots surrender completely. O'Higgins wanted to defend the city of Rancagua. Carrera, however, wanted to fight at Angostura, a better defensive spot closer to Santiago. Because of their disagreements, the Patriot forces were split. O'Higgins had to face the Royalists at Rancagua without enough help.

The Disaster of Rancagua happened on October 1 and 2, 1814. It was a fierce battle, but the Patriots suffered a terrible defeat. Only 500 out of 5,000 soldiers survived. Soon after, Osorio entered Santiago, ending the Patria Vieja period.

The Reconquest (Reconquista): Spain Fights Back

Viceroy Abascal confirmed Mariano Osorio as the new governor of Chile. Later, Osorio was replaced by Francisco Casimiro Marcó del Pont in 1815. The Spanish wanted to punish the revolutionaries. They started a harsh campaign against Patriots, led by Vicente San Bruno. Many Patriots in Santiago, including members of the First Junta, were sent away to the Juan Fernández Islands.

These actions did not stop the Patriots. Instead, they made even the most moderate Chileans realize that only full independence would be enough. Many Patriots, including Carrera and O'Higgins, fled to Mendoza, a province in newly independent Argentina.

The governor of Mendoza was José de San Martín, a key leader of Argentina's independence movement. San Martín quickly favored O'Higgins. Carrera's influence faded, and he was later executed in 1821.

While San Martín and O'Higgins prepared an army to cross the Andes mountains and retake Santiago, they gave a special task to a lawyer named Manuel Rodríguez. His job was to lead a guerrilla campaign. This meant making small, surprise attacks to keep the Spanish forces busy and to boost the spirits of the Patriots.

Rodríguez became a famous hero for his brave actions. In one story, he dressed as a beggar and even got money from Governor Marcó del Pont himself, who had offered a reward for Rodríguez's capture.

By 1817, the "Army of the Andes" was ready. After a difficult journey crossing the Andes, they met the Royalist forces at Chacabuco, north of Santiago. The Battle of Chacabuco on February 12, 1817, was a big victory for the Patriots. They re-entered Santiago. San Martín was offered the role of Supreme Director, but he refused and gave it to O'Higgins. O'Higgins would lead Chile until 1823. On the first anniversary of the Battle of Chacabuco, O'Higgins officially declared Chile's independence.

The New Homeland (Patria Nueva): Securing Independence

Meanwhile, a new Spanish viceroy, Joaquín de la Pezuela, was in charge in Peru. He sent Mariano Osorio back to Chile with another army. These troops landed in Concepción and gathered many local people to join them. Bernardo O'Higgins moved north to try and stop the Royalists.

However, O'Higgins' forces were surprised and badly defeated at the Second Battle of Cancha Rayada on March 18, 1818. During the confusion, a false rumor spread that San Martín and O'Higgins had died. Patriot soldiers panicked and wanted to retreat back to Argentina. In this difficult moment, Manuel Rodríguez stepped forward. He rallied the soldiers, shouting, "There's still a country, citizens!" He even named himself Supreme Director for about 30 hours, until O'Higgins, who was wounded but alive, returned to Santiago and took back command.

Then, on April 5, 1818, San Martín led the Patriots to a major victory over Osorio at the Battle of Maipú. After this defeat, the Royalists retreated to Concepción and never launched another big attack on Santiago. Chile's independence was almost certain. Any worries about disagreements among the Patriots ended when O'Higgins greeted San Martín as the country's savior. This famous moment is known as the Embrace of Maipú.

The Fight Continues: Total War

To make sure Chile was truly independent, San Martín fought against armed groups in the mountains. These groups included outlaws, Royalist supporters, and local people who took advantage of the chaos to rob the countryside. This period of fighting was called the Guerra a muerte (War to the Death). It was called this because neither side took prisoners. The fighting was very harsh. This region around Concepción was finally peaceful in 1822, after the group led by Vicente Benavides was defeated.

Taking Back Valdivia and Chiloé

While San Martín worked on peace inside Chile, O'Higgins focused on defending the country from future Spanish attacks. He also wanted to remove all Spanish control. He built up the Chilean navy and put a brave Scotsman, Lord Cochrane, in charge as admiral.

In 1820, Cochrane made a surprising and successful attack on the strong Spanish forts at Valdivia. Later, Cochrane sent troops to Chiloé Island to capture the last Spanish stronghold in Chile, the Archipelago of Chiloé. This attempt failed after a small but important battle called the Battle of Agüi. Later, Georges Beauchef led an expedition from Valdivia to secure Osorno. This was to prevent the Spanish from retaking Valdivia by land. Beauchef won a big victory over the Royalists at the Battle of El Toro.

Both San Martín and O'Higgins agreed that Chile would not be safe until Peru was also free from Spain. So, they prepared a fleet and an army to go to Peru. In 1820, San Martín and Cochrane sailed to Peru. However, Cochrane was very bold, while San Martín was very careful. San Martín missed chances to strike a final blow against the Spanish in Peru. In the end, it was Simón Bolívar who led the final attack after coming from Colombia. Peruvian independence was secured after the Battle of Ayacucho on December 9, 1824. In this battle, forces led by Antonio José de Sucre, one of Bolívar's generals, finally defeated the Royalist army.

In Chilean history, the Patria Nueva period usually ends in 1823, when O'Higgins resigned. However, the very last Spanish territory in Chile, the Chiloé archipelago, was not fully conquered until 1826. This happened during the government of Ramón Freire, who took over after O'Higgins.

How the War Affected Chile's Economy

The wars for independence in Chile (1810–1818) and Peru (1809–1824) had a negative effect on Chile's wheat farming. Trade was interrupted, and armies often took supplies from the countryside. The Guerra a muerte phase was especially damaging. After the war, there was a period of outlaw banditry until the late 1820s. Trade with Peru did not fully recover after the independence struggles. The city of Valdivia, which relied on sea trade with Peru, was hit very hard. Its luck only changed when German settlers arrived in the late 1840s.

Much of the money for the war came from silver mines in Agua Amarga, discovered in 1811. In 1811, Chile started a free trade policy. This allowed the country to benefit from the California Gold Rush and the Australian gold rushes in the mid-19th century by exporting wheat.

In 1822, Bernardo O'Higgins' government got a large loan from London to help pay for the independence fight. It took many years to pay back this "Chilean independence debt." It was finally settled in the 1840s, thanks to the work of finance ministers Manuel Rengifo and Joaquín Tocornal, and good prices for Chilean silver, copper, and wheat.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de la Independencia de Chile para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de la Independencia de Chile para niños

- Argentine War of Independence

- Antonio de Quintanilla

- Antonio Pareja

- Antonio José de Sucre

- Bernardo O'Higgins

- Camilo Henríquez

- Charlotte Joaquina

- Francisco García Carrasco

- Francisco Marcó del Pont

- Ferdinand VII

- Founding of Talca

- Gabino Gaínza

- Juan Albano Pereira Márquez

- Georges Beauchef

- Logia Lautaro

- Lord Thomas Cochrane

- Manuel Rodríguez

- Mariano Osorio

- Mateo de Toro Zambrano

- Joaquín de la Pezuela

- Luisa Recabárren de Marin

- José de San Martín

- José Fernando de Abascal

- José Miguel Carrera

- José Miguel Infante

- Juan Martínez de Rozas

- Ramón Freire

- Rafael Maroto

- Simón Bolívar

- Vicente Benavides

- Vicente San Bruno

- William Miller