Battle of Ayacucho facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Ayacucho |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Peruvian War of Independence | |||||||

The Battle of Ayacucho, Antonio Herrera Toro |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,780–8,500 | 6,906–9,310 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 370 killed 609 wounded |

1,800 killed 700 wounded 2,000–3,000 captured |

||||||

The Battle of Ayacucho was a super important fight during the Peruvian War of Independence. This battle helped Peru become free and also made sure other parts of South America gained their independence from Spain. In Peru, it's seen as the end of the Spanish American wars of independence there. Even though the main battle was over, fighting continued in some areas until 1826.

By late 1824, the Royalists (those loyal to Spain) still controlled much of southern Peru. They also held a strong fort called Real Felipe in Callao. On December 9, 1824, the Battle of Ayacucho happened. It was fought between the Royalist and Independentist (Patriot) armies at Pampa de Ayacucho, near the town of Quinua.

The Independentist forces were led by Antonio José de Sucre, who was a top general for Simón Bolívar. During the battle, the Royalist leader, José de la Serna, was hurt. After the fight, his second-in-command, José de Canterac, signed a paper that officially surrendered the Royalist army. Today, the modern Peruvian Army celebrates this battle every year.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

In January 1820, Spain had a big political change. There was a revolt against King Ferdinand VII. An army of 20,000 soldiers was supposed to go to South America to help the Royalists there. But instead, these soldiers revolted in Spain, led by General Rafael Riego.

This revolt spread, and King Ferdinand had to bring back the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812. This meant Spain couldn't send more soldiers to America. So, the Royalist armies in places like Peru and Mexico had to fight the Patriots on their own.

In Mexico, the Royalists and Patriots agreed to separate from Spain peacefully. But in Peru, things were different. Because Spain couldn't send help, the Patriot forces started winning. Leaders like José de San Martín made progress in Peru. This made the Spanish leader in Peru, Joaquín de la Pezuela, unpopular. He was removed from power in 1821 by General José de la Serna.

The Patriots had some early wins, like at Cerro de Pasco. But the Royalists were well-trained and strong. They defeated Patriot armies in several battles. By 1823, José de San Martín had left, and the Royalists continued to win. They defeated Patriot armies led by Rudecindo Alvarado and Andrés de Santa Cruz.

At the same time, some Patriot leaders in Peru were accused of treason. This made the situation even harder for the Patriots. But by the end of 1823, the Royalists were also in trouble. Simón Bolívar was asking for more soldiers from Colombia, which made him a big threat. Both sides knew a major battle was coming.

Truce and Mutiny

Some people tried to make peace. In 1823, Buenos Aires made a temporary peace agreement with Spain. This agreement would stop fighting for a year and a half. But other South American governments had to agree to it too. This truce worried some Patriot leaders because it seemed like Buenos Aires was pulling out of the fight.

Then, in January 1824, Simón Bolívar became very sick. Around the same time, a big problem happened in Callao, Peru. On February 4, 1824, soldiers in the Callao forts mutinied. Many soldiers, including Argentines, Chileans, Peruvians, and Colombians, joined the Royalists. They raised the Spanish flag and gave the forts to the Royalists.

Another group of soldiers also mutinied, but when they realized they were joining the Royalists, many of them went back to the Independentists. These events meant the war would continue longer. Lima was even taken over by the Royalists for a short time.

Olañeta's Rebellion

At the start of 1824, the Royalist army in Upper Peru (which is now Bolivia) had its own rebellion. General Pedro Antonio Olañeta led this revolt against the Spanish leader in Peru, José de la Serna. This happened because King Ferdinand VII had taken back full control in Spain. He had canceled all the changes made by the liberal government, including La Serna's appointment as leader in Peru.

Olañeta, who supported the king's absolute rule, attacked the Royalist forces loyal to La Serna. This caused a big split within the Royalist army. They started fighting each other. This fighting weakened both sides of the Royalist army.

Simón Bolívar heard about Olañeta's actions. He saw that the Royalist defenses were now weaker. So, he moved his army to face José de Canterac, who was now alone. Many Royalist soldiers even left their side and joined the Independentists. By October 1824, Bolívar was near Cusco. He gave command of the army to General Sucre and went to Lima to get more money and soldiers for the war.

The Ayacucho Campaign

After José de Canterac's defeat, José de la Serna ordered General Jerónimo Valdés to bring his troops from Potosí. The Royalist generals argued about what to do. Even though they had support in Cusco, La Serna didn't want to attack directly because his army wasn't fully trained. Many new soldiers had joined only weeks before.

Instead, La Serna planned to cut off Sucre's army by moving around them. This led to a clash on December 3, 1824, at Battle of Corpahuaico or Matará. The Royalists caused over 500 casualties to the Patriot army and captured much of their supplies. But Sucre managed to keep his troops organized and retreat in good order.

The Patriot army had many experienced soldiers. For example, some units had European soldiers, including British volunteers. These soldiers had fought in other wars around the world. General William Miller, a British officer, fought with Bolívar's forces.

The Royalists were tired from all the marching and fighting. They hadn't won a big victory. Both armies were suffering from sickness and soldiers leaving. The Royalist commanders took a good defensive spot on Kunturkunka hill. But they only had enough food for a few days. They knew that if Colombian soldiers arrived, they would be defeated. So, the Royalist army had to make a desperate choice: fight the Battle of Ayacucho.

Armies Ready for Battle

People disagree on the exact number of soldiers on each side. But at first, both armies had similar numbers (around 8,500 Patriots vs. 9,310 Royalists). However, these numbers went down before the battle. On the day of the battle, there were probably about 5,780 Patriots and 6,906 Royalists.

United Liberation Army (Patriots)

- Commander: Marshal Antonio José de Sucre

- Chief of High Command: General Agustín Gamarra

- Cavalry: General William Miller

- First Division: General José María Córdoba (2,300 men)

- Second Division: General José de La Mar (1,580 men)

- Reserve: General Jacinto Lara (1,700 men)

Before the battle, Sucre spoke to his soldiers:

"Soldiers, South America's future depends on what we do today. Another day of glory will reward your amazing hard work. Soldiers, Long live the Liberator! Long live Bolívar, the Savior of Peru!"

Royalist Army of Peru

- Commander: Viceroy José de la Serna

- Chief of the High Command: Lieutenant General José de Canterac

- Cavalry Commander: Brigadier Valentín Ferraz

- Vanguard Division: General Jerónimo Valdés (2,006 men)

- First Division: General Juan Antonio Monet (2,000 men)

- Second Division: General Alejandro González Villalobos (1,700 men)

- Reserve Division: General José Carratalá (1,200 men)

The Battle Begins

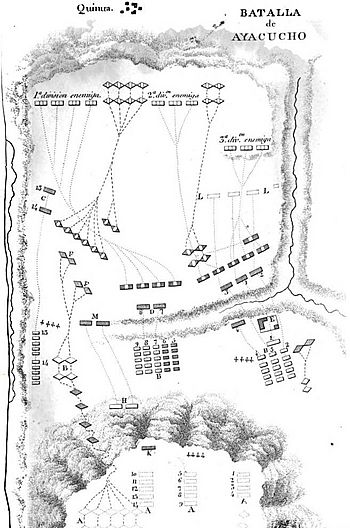

- Royalists positions in the night from 8 to 9

- Preparatory maneuver for the royalist attack

- March of battalions under colonel Rubín de Celis

- Maneuver and attack of Monet division

- Attack of Valdés’ vanguard over the house occupied by the independentists

- Charge of royalist cavalry

- and dispersion of Gerona battalions by the royalist reserve

- Battalion Ferdinand VII, last royalist reserve

The Royalists planned to attack by moving down from the Condorcunca hill. They hoped to surprise the Patriot army. But as they moved, they became exposed and disorganized. General José María Córdova's Patriot division, supported by cavalry, attacked the Royalist troops. The Royalists couldn't form their battle lines properly as they came down the mountain.

As the attack started, General Córdova famously shouted: "Division, arms at ease; at the pace of victors, forward!" The Royalist colonel Joaquín Rubín de Celis moved his unit carelessly into the open, where it was badly hit. He was killed during the attack.

Seeing this, Royalist general Monet led his division forward. But the Patriots attacked quickly, surrounding him before his troops could get into formation. Monet was wounded, and his division was scattered. The Royalist cavalry tried to help, but the confusion and gunfire caused many losses.

On the other side of the battle, the Patriot divisions of José de La Mar and Jacinto Lara stopped the attack by Valdés’ Royalist vanguard. The Patriots were reinforced and pushed back.

Viceroy La Serna and other Royalist commanders tried to get their scattered soldiers back in order. General Canterac led the reserve division, but these soldiers were new and quickly broke apart. The last Royalist battalion also gave up after a short fight. By one o'clock, the Viceroy was wounded and captured, along with many of his officers. Even though Valdés’ division was still fighting, the battle was a clear victory for the Patriots.

The Patriots had about 370 killed and 609 wounded. The Royalists lost about 1,800 killed and 700 wounded. With their main army destroyed and their leader captured, the Royalist leaders surrendered.

The Surrender at Ayacucho

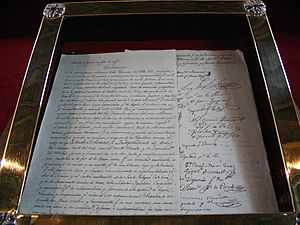

Since Viceroy de la Serna was badly hurt, the surrender agreement was negotiated by Royalist commander Canterac and Patriot general Sucre. The main points of the agreement were:

- The Royalist army agreed to stop fighting.

- Any remaining Royalist soldiers would stay in the Callao forts.

- The new Peruvian republic would pay back the countries that helped with the independence movement.

In Lima, Simón Bolívar called for a meeting called the Congress of Panama to unite the new independent countries. Only Gran Colombia (a large country that included present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama) agreed to this idea. But later, Gran Colombia split into the countries we know today. This was sad for Bolívar, who dreamed of a united South America.

Some historians have debated if there was a secret agreement before the battle. They suggest that some Royalist commanders, who didn't like King Ferdinand VII's absolute rule, might have preferred a Patriot victory. However, there's no clear proof, and the commanders involved kept quiet about it.

What Happened Next

After the victory at Ayacucho, General Sucre followed Bolívar's orders and entered Upper Peru (modern-day Bolivia) in February 1825. He was told to set up an independent government there. Royalist general Pedro Antonio Olañeta was still in Potosí and wanted to keep fighting for King Ferdinand VII.

But many Spanish soldiers in Upper Peru were tired of fighting. In Cochabamba, a Royalist battalion rebelled and joined the independence movement. Other units followed. On April 2, 1825, Colonel Medinacelli, who had rebelled against Olañeta, fought him in the Battle of Tumusla. Olañeta was killed. A few days later, on April 7, general José María Valdez surrendered. This ended the war in Upper Peru, which had been fighting for independence since 1811.

Bolivia Becomes Independent

Sucre called a meeting in Chuquisaca on July 8, 1825. This meeting declared Upper Peru completely independent and a new republic. The "Independence Act of the Upper Peruvian Departments" was signed on August 6, 1825. This date honored the Battle of Junín won by Bolívar. The declaration stated:

"The world knows that the land of Upper Peru has been, in the American continent, the altar where the free people shed the first blood, and the land where the last of the tyrants’ tombs finally lays. Today, the Upper Peruvian departments, united, protest in the face of the whole Earth its irrevocable resolution to be governed by themselves."

How Bolivia Got Its Name

A law was passed that the new country in Upper Peru would be named República Bolívar, to honor the liberator, Simón Bolívar. He was called "Father of the Republic and Supreme Chief of State." Bolívar thanked them but didn't want to be president. He gave that job to the winner of Ayacucho, Grand Marshal Antonio José de Sucre, who became the first President of Bolivia.

Later, they talked about the country's name again. A representative from Potosí, Manuel Martín Cruz, suggested that just as Rome came from Romulus, Bolivia could come from Bolívar.

"If from Romulus, Rome; from Bolívar, it is Bolivia".

Bolívar was pleased, but he was also worried about the new country's future. It was in the middle of South America, which he thought might lead to many wars. He wished Bolivia would join another nation, like Peru or Argentina. But the people's strong desire for independence changed his mind. When he visited cities like La Paz, Oruro, Potosí, and Chuquisaca, the people cheered for him. This touching support made Bolívar call the new nation his "Predilect Daughter." The people of the new republic called him their "Favorite Son."

Bolívar Praises Sucre

In 1825, Bolívar wrote about General Sucre. He praised Sucre's amazing achievement at Ayacucho:

"The Battle of Ayacucho is the highest point of American glory, and it was General Sucre's work. The plan for it was perfect, and how it was carried out was amazing. Future generations will remember the victory of Ayacucho to celebrate it and see it as a symbol of freedom, telling Americans to use their rights and follow the sacred laws of nature."

"You are meant for the greatest things, and I see that you are a rival to my own Glory" (Bolivar, Letter to Sucre, Nazca, April 26, 1825).

"Then the Congress of Colombia made Sucre Chief General of the Colombian Army and its Commanding General, and the Congress of Peru gave him the title and military rank of Great Marshal of Ayacucho because of his actions."

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Ayacucho para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Ayacucho para niños

- Battle of Junín

- Ayacucho Declaration

- British Legions