Royalist (Spanish American independence) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Royalist |

|

|---|---|

| Realistas | |

|

|

| Leaders | |

| Dates of operation | 1810–1829 |

| Allegiance | Spanish Empire |

| Motives | Preservation of the territorial integrity of Spain |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | Patriot Governments (Spanish American independence) |

The royalists were people in Hispanic America and Europe who fought to keep the Spanish Empire together. They were active during the Spanish American wars of independence, which lasted from 1810 to 1829.

In the early years, Spain's King Ferdinand VII was held captive in France. During this time, royalists supported the Supreme Central Junta and the Cortes of Cádiz. These groups ruled in the King's name during the Peninsular War in Spain.

Later, when Ferdinand VII returned to power in 1814, royalists split into two groups. Some were "Absolutists," who wanted the King to rule with old, traditional laws. Others were "Liberals," who wanted to bring back the reforms made by the Cortes of Cádiz.

Contents

How Politics Changed for Royalists

The creation of local governments, called juntas, in Spanish America in 1810 was a direct response to events in Spain. In 1808, Napoleon forced King Ferdinand VII to give up his throne. Napoleon then made his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, king of Spain.

A group called the Supreme Central Junta led the fight against Joseph's government and the French. But they lost control of much of Spain. In February 1810, French troops took Seville, a major city. The Supreme Junta moved to Cádiz and formed a new government called the Regency Council.

News of these events reached Spanish America over several months. This caused big disagreements. Some royal officials and Spanish Americans wanted things to stay the same. They believed the existing government should continue, no matter what happened in Spain. Others thought it was time for local rule. They wanted to create juntas to protect Spanish America from French control or a weak Spanish government.

It's important to know that these early juntas still claimed to act in the name of the captured King. They did not immediately declare independence. Juntas were successfully formed in Venezuela, Río de la Plata, and New Granada.

Royalists vs. Patriots

After the Regency Council was formed, it became clear that Spain was not completely lost. The government began to rebuild itself. The Regency held a meeting of the Cortes Generales, Spain's traditional parliament. This meeting included representatives from Spanish America.

The Regency and Cortes started giving orders and appointing officials across the empire. Those who supported this new Spanish government were called "royalists." Those who wanted to keep the independent local juntas were called "patriots." Some patriots even wanted full independence from Spain.

As the Cortes introduced new laws and worked on a constitution, a new split appeared among royalists. "Conservatives" (also called "absolutists") did not want any changes to the government. "Liberals" supported the new reforms. These differences became even bigger when King Ferdinand VII returned, as he chose to support the conservatives.

Local Rivalries and the War

Local rivalries also played a big part in the wars in Spanish America. When the central Spanish authority disappeared, many regions started fighting among themselves. It was unclear which local groups should take over. There were no strong new national identities.

The early juntas in 1810 appealed to different feelings. First, they appealed to being Spanish, against the French threat. Second, they appealed to a general American identity, seeing Spain as lost to the French. Third, they appealed to loyalty to their local province, or patria.

Often, juntas wanted their province to be independent from the capital of their former viceroyalty, not just from Spain. This led to armed conflicts between provinces. This happened a lot in New Granada and Río de la Plata.

Sometimes, regions even joined the opposite side just because of their rivals. For example, Peru stayed strongly royalist partly because of its rivalry with Río de la Plata. Peru had lost control of Upper Peru to Río de la Plata in 1776. When juntas formed in Río de la Plata, Peru was able to regain control of Upper Peru during the wars.

King Ferdinand VII Returns

When King Ferdinand VII was restored to the throne, it brought big changes. Many political and legal changes had been made in his name while he was gone. This included the juntas, the Cortes in Spain, and new constitutions.

Once in Spain, Ferdinand VII saw that he had strong support from conservatives and the Spanish Catholic Church. So, on May 4, he rejected the Spanish Constitution of 1812. He also ordered the arrest of the liberal leaders who created it.

Ferdinand said that the Constitution and other changes were made without his permission. He also declared all the juntas and constitutions in Spanish America invalid. He brought back the old laws and political systems.

This decision created a clear break with two groups who could have been his allies. These were the local governments that had not yet declared independence. It also alienated Spanish liberals who wanted a representative government that included the Americas.

The provinces of New Granada had been independent from Spain since 1810. Unlike Venezuela, where royalists and independence fighters had often changed control. To regain Venezuela and New Granada, Spain sent its largest army ever to the Americas in 1815. This force had 10,500 troops and nearly sixty ships.

This army helped retake New Granada. However, its soldiers were spread out across Venezuela, New Granada, Quito, and Peru. Many were lost to tropical diseases. More importantly, most royalist forces were not soldiers from Spain. They were Spanish Americans.

Some Spanish Americans were moderates. They decided to wait and see what would happen. In some areas, governors kept the elected local councils (ayuntamientos) for several years. This helped prevent conflict with local people.

Liberals on both sides of the Atlantic continued to plan to bring back a constitutional monarchy. They finally succeeded in 1820. Ferdinand's actions pushed areas not controlled by royalist armies towards full independence. These regions, which started with the juntas of 1810, now saw the need to separate from Spain. They wanted to protect the reforms they had made.

New Constitution and Independence

Spanish liberals finally forced Ferdinand VII to restore the Constitution on January 1, 1820. This happened when Rafael Riego led a rebellion among troops. These troops were supposed to be sent to the Americas. By March 10, Ferdinand VII, now almost a prisoner, agreed to restore the Constitution.

Riego's revolt had two big effects on the war in the Americas. First, the large number of reinforcements needed in New Granada and Peru never arrived. Second, as the royalist situation worsened, many army units switched sides to the patriots.

The new liberal government thought the rebels were fighting for Spanish liberalism. They believed the Spanish Constitution could still unite both sides. The government put the Constitution into effect and held elections in the overseas provinces. It also told military commanders to negotiate with the rebels. They promised that rebels could join the new representative government.

However, the Spanish Constitution actually helped lead to independence in New Spain (Mexico) and Central America. In these regions, a group of conservative and liberal royalist leaders helped create new states. The return of the Spanish Constitution was welcomed in New Spain and Central America. Elections were held, local governments formed, and representatives were sent to the Cortes.

But liberals worried the new system would not last. Conservatives and the Church feared the new liberal government would make more reforms and anti-church laws. This unstable situation led both sides to form an alliance. This alliance formed in late 1820 behind Agustín de Iturbide. He was a colonel in the royal army.

Iturbide was supposed to destroy the rebel forces led by Vicente Guerrero. Instead, Iturbide negotiated with Guerrero. This led to the Plan of Iguala. This plan would make New Spain an independent kingdom, with Ferdinand VII as its king. The highest Spanish official in Mexico approved the Treaty of Córdoba. Although Spain never officially agreed to this treaty, it could not stop it. The royal army in Mexico ultimately brought about Mexico's independence.

Central America gained its independence along with New Spain. Local leaders supported the Plan of Iguala. They arranged for Central America to join the Mexican Empire in 1821. Two years later, after Iturbide's rule ended, the region peacefully left Mexico in July 1823. They formed the Federal Republic of Central America. This new state lasted seventeen years before its provinces split apart.

In South America, independence was driven by the pro-independence fighters who had held out for years. José de San Martín and Simón Bolívar led a large attack from the south and north of South America. This freed most of the Spanish American nations on that continent.

In South America, royalist soldiers and units also began to leave or switch to the patriot side in large numbers. This happened as the royal army's situation became desperate. Unlike in Mexico, the top military and political leaders in these parts of South America came from the patriot side, not the royalists.

The fall of the constitutional government in Spain in 1823 had other effects. Royalist officers, split between liberals and conservatives, fought among themselves. General Pedro Antonio Olañeta, a commander in Upper Peru, rebelled against the liberal viceroy of Peru, José de la Serna, in 1823.

This conflict allowed the republican forces under Bolívar and Antonio José de Sucre to advance. This led to the Battle of Ayacucho on December 9, 1824. The royal army of Upper Peru surrendered after Olañeta was killed on April 2, 1825. However, former royalists played an important role in creating Peru and Bolivia.

Royalist Army Structure

Motto: Por la Religión, la Patria y el Rey. Viva Fernando VII (For Religion, the Homeland, and the King. Long Live Ferdinand VII)

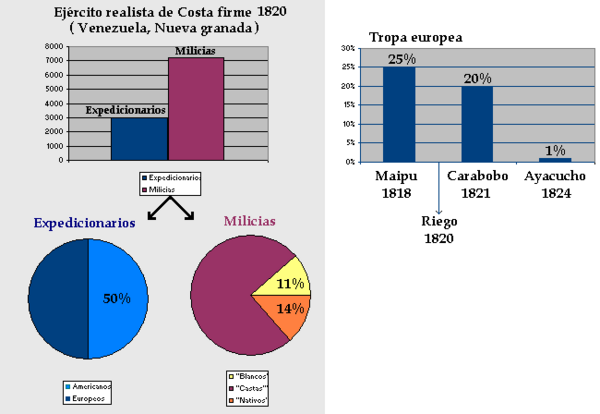

The royalist army had two main types of units. Expeditionary units were created in Spain and sent to America. Militias were units that already existed or were formed in America during the conflict.

The militias were made up entirely of local residents or natives of Spanish America. They were supported by "veteran units." These veteran units had soldiers from Spain and Spanish America who had fought in Spain's wars around the world. Veteran units were meant to provide experienced soldiers. Their skills were very valuable to the regular militiamen, who often lacked military experience.

Overall, Europeans made up only about one-tenth of the royalist armies in Spanish America. They were about half of the expeditionary units. As European soldiers were lost, they were replaced by Spanish American soldiers. So, over time, there were more and more Spanish American soldiers in the expeditionary units.

For example, Pablo Morillo, a commander in Venezuela and New Granada, reported he only had 2,000 European soldiers. This meant only half of his expeditionary force was European. It's estimated that in the Battle of Maipú, only a quarter of the royalist forces were European. In the Battle of Carabobo, it was about a fifth, and in the Battle of Ayacucho, less than 1% were European.

The American militias showed the different racial groups of the local population. For instance, in 1820, the royalist army in Venezuela had 843 white soldiers, 5,378 Casta (mixed-race) soldiers, and 980 Native soldiers.

The last royalist armed group in what is now Argentina and Chile was the Pincheira brothers. This was an outlaw gang made of Europeans, American Spaniards, Mestizos (mixed European and Native), and local indigenous people. They were originally based in Chile but moved across the Andes to Patagonia. They formed an alliance with indigenous tribes. In Patagonia, far from Chilean and Argentine control, the Pincheira brothers set up a permanent camp with thousands of settlers.

Important Royalist Leaders

| Río de la Plata and Pacific Ocean | Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea |

|

Commanders

Strongholds

|

Commanders

|

See also

In Spanish: Ejército realista en América para niños

In Spanish: Ejército realista en América para niños

- Spanish American wars of independence

- Spanish expeditionary army order of battle

- Reconquista (Spanish America)

- Loyalist (American Revolution), the equivalent of the Royalist in Anglo-America