Captaincy General of Puerto Rico facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Captaincy General of Puerto Rico

Capitanía General de Puerto Rico

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1580–1898 | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Anthem: National anthem of Spain

|

|||||||||||

Location of Puerto Rico

|

|||||||||||

| Status | Captaincy General | ||||||||||

| Capital | San Juan | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish | ||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism, Espiritismo | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

|

• 1580–1598

|

Philip II | ||||||||||

|

• 1759–1788

|

Charles III | ||||||||||

|

• 1886–1898

|

Alfonso XIII Maria Christina of Austria (Regent) |

||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

|

• 1580

|

Jerónimo de Agüero Campuzano | ||||||||||

|

• 1898

|

Ricardo de Ortega y Díez | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern Europe | ||||||||||

|

• Administrative reorganisation

|

1580 | ||||||||||

| 1898 | |||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish real, Puerto Rican peso | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | PR | ||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Today part of | United States | ||||||||||

The Captaincy General of Puerto Rico (which in Spanish was called Capitanía General de Puerto Rico) was a special way the Spanish Empire managed the island of Puerto Rico. It was created in 1580 to help Spain better control the island's military. Before this, Puerto Rico was just ruled by a single governor.

This new system was part of Spain's efforts to stop other countries from trying to take over parts of the Caribbean. Spain also set up similar Captaincies General in places like Cuba, Guatemala, and Yucatán.

The Captaincy General was very important for the Spanish Caribbean. It lasted in Puerto Rico until 1898. That year, Puerto Rico got its own local government with a governor-general and a parliament. But just a few months later, Spain gave Puerto Rico to the United States after losing the Spanish–American War.

Contents

History of Puerto Rico's Government

Early Days: Governors and Councils

In 1508, Juan Ponce de León was sent by the Spanish Crown to start colonizing Puerto Rico. He founded the city of Caparra (now Guaynabo) and became its first governor in 1509.

However, the Spanish Crown and the family of Christopher Columbus had disagreements about who could appoint governors in the Americas. In 1511, a court decided that Diego Colón, Columbus's son, had the right to appoint governors. Because of this, Ponce de León lost his job and left the island.

The Columbus family then appointed governors in Puerto Rico until 1536. That year, Luis Colón, Diego's son, sold his rights to govern the Indies back to the Crown.

From 1536 to 1545, the island was overseen by the head of the Audiencia of Santo Domingo, who was also the Captain General of the Caribbean. Locally, the island was managed by alcaldes ordinarios. These were local leaders elected each year by the town councils, called cabildos, in San Juan and San Germán. Since many of these local leaders weren't trained to be governors, this system didn't work very well. The Spanish residents on the island complained to the Crown.

Starting in 1545, governors who had legal training were appointed. These governors were the highest judges on the island. They heard cases and also oversaw the local alcaldes. The next level of appeal was the Audiencia in Santo Domingo. Governors also had power because they could appoint some members of the local cabildos.

Governors were also the king's top representatives. This meant they had some control over the Church on the island. They oversaw building churches, paid clergy salaries, and made sure only approved Church documents were published.

Why the Captaincy General Was Created

Spain was getting into more military conflicts with other European countries. Because of this, in 1580, the Crown added the title of "Captain General" to the governor's job. After this, most governors were military men, not lawyers. They had legal advisors to help them with their judicial and administrative duties.

Puerto Rico's Importance and Defenses

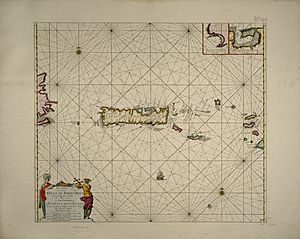

Spain saw Puerto Rico as very important strategically, even if it wasn't rich. It was called "the key to the Indies." Because of ocean currents and wind patterns, ships coming from Europe usually stopped in Puerto Rico first.

However, Spain was slow to build up the island's defenses. The first fortified building was Ponce de León's family home in the 1520s. Later, construction began on the first real fort, La Fortaleza. By 1539, a full defense system was being built around San Juan. This included forts like San Felipe del Morro, San Cristóbal, and San Gerónimo. San Germán, on the other side of the island, was left mostly unprotected and was often attacked by the French.

With the creation of the Captaincy General in 1580, Governor-Captain General Diego Menéndez de Valdés (1582–1593) continued to strengthen San Juan's defenses. To pay for this and for more soldiers, Spain ordered an annual payment called the situado from the royal treasury in New Spain (Mexico). However, for the next two centuries, this money often didn't reach Puerto Rico.

The number of permanent soldiers increased from about 50 to over 200, and then to over 400 by 1596. These improved defenses were ready when they faced a big challenge: an attack by a fleet of 27 ships led by Francis Drake.

Puerto Rico also served as an important base in Spain's fight against piracy by its rivals. Many Puerto Ricans became Spanish privateers. These were like legal pirates who attacked British, French, and Dutch ships. The most famous privateer was Miguel Henríquez. During these times, illegal trade, called contraband, became a big part of the local economy.

To help the regular soldiers, local militias (milicias urbanas) were formed in the island's five districts outside the capital. These militia men were not paid regularly or given weapons by the government. They used farm tools like machetes and knives. Each district was overseen by a teniente a guerra, who was a deputy of the captain general.

Changes in the 18th Century

Bourbon Reforms and O'Reilly

After losing Cuba to the British in 1762 during the Seven Years' War, King Charles III sent officials to the Caribbean to check on defenses. Alejandro O'Reilly was sent to Puerto Rico in 1765.

O'Reilly suggested many changes, and some were put into action:

- Improving the forts in San Juan.

- Paying soldiers directly and regularly.

- Making the local militias more professional.

- He also took a complete count of the island's people, finding 44,883 residents, including 5,037 enslaved people.

O'Reilly realized how much illegal trade was happening. To fix this, he suggested growing the legal economy, especially farming. He wanted to give unused land to people willing to farm it. In 1784, a new financial office called an intendancy was created in Puerto Rico.

O'Reilly's military reforms were very successful. However, he couldn't change the economy much. The island's economy still relied on the situado payment and foreign trade. This caused problems when trade was interrupted by the Napoleonic Wars.

Early 19th Century: Revolutions and New Ideas

The early 19th century brought two big challenges for Spain: being invaded by French forces and facing revolts in its colonies in the Americas. Puerto Rico's close ties to Venezuela, due to sailing routes, played a role here.

Local councils in Puerto Rico were in touch with groups in Venezuela that wanted independence. The San Juan council turned down an invitation to form its own independent group. But the San Germán council always believed it had the right to self-rule if Spain was lost to the French. Some Puerto Ricans, like Antonio Valero de Bernabé, even joined the fight for independence in South America.

Spain's government, fighting the French, gave Governor Salvador Meléndez special powers to stop any revolts on the island. Many loyal Spanish people from Venezuela also started arriving in Puerto Rico. The island also became a place where Spanish troops gathered before heading to Venezuela.

As Spain's government against the French took shape, it recognized its overseas lands as part of the Spanish nation. In 1809, it invited them to send representatives. This led to a period of elections in Puerto Rico, where people had more say. This included the time of the Spanish Constitution of 1812 (1812-1814 and 1820-1823).

The first elections were held by the cabildos (town councils). They elected Ramón Power y Giralt as Puerto Rico's representative. Power was very active in the Spanish parliament, called the Cortes of Cádiz. He quickly got the Cortes to take away the governor's special powers. He also made sure the financial office (intendant) was separate from the governor's job.

Power's most important work was the Ley Power (Power Act). This law brought many administrative and economic changes to Puerto Rico. Many of these changes lasted even after King Ferdinand VII got rid of the Constitution and the Cortes. The Spanish Constitution also brought local government to Puerto Rico, with more elected cabildos and a local legislative board called the Diputación Provincial.

After the King restored traditional government, he wanted to reward Puerto Ricans for their loyalty. He gave the island a limited form of free trade, which they had wanted for a long time. The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 granted many of the economic requests. This decree had very good economic effects in the long run. It encouraged Europeans who were not Spanish to move to the island. It also started the growth of the sugar industry, which led to more enslaved people being brought in.

During a second period of constitutional government (1820-1823), new representatives were elected to the Cortes. The Diputación Provincial met again. An important change was that the captaincy general and the governorship were separated. Miguel de la Torre was appointed captain general.

After Ferdinand VII again got rid of the Constitution, La Torre became both governor and captain general. He had special powers to stop any revolts. He held this job for over 15 years. Even though La Torre was careful about liberal ideas, his long time in office was key to the growth of large-scale sugar production on the island. This type of farming had started decades earlier in Cuba.

Figures show how much things grew:

- In 1820, Puerto Rico produced 17,000 tons of sugar. Only 5.8% of the land was farmed.

- By 1897, Puerto Rico produced 62,000 tons of sugar. 14.3% of its land was used for farming.

- Small landholdings, which had been common, were bought to create large plantations.

After sugar, coffee was the second most important crop. In 1818, 70 million pounds of coffee were produced. This grew to 130 million pounds by 1830. More farming meant more enslaved workers were brought from other Caribbean islands. Spain had agreed to outlaw the slave trade in 1817, but it wasn't strictly enforced until after 1845. However, in Puerto Rico, enslaved people made up only 11.5% to 14% of the workforce, which was much lower than on other Caribbean islands.

For legal matters, Puerto Rico had its own high court, called an audiencia, from 1832 to 1853. Before that, appeals were heard in Cuba.

Towards Autonomy in the Late 1800s

The death of Ferdinand VII brought new changes. The Queen Regent, María Cristina, brought back the Cortes (parliament), and Puerto Rico sent several representatives who supported liberal ideas. In 1836, constitutional government was restored in Spain.

However, this government saw overseas territories like Puerto Rico as colonies that should be ruled by special laws. The democratic groups, like the Diputación Provincial and the cabildos, were removed. The special powers given to the governor were kept. The new Constitution of 1837 confirmed Puerto Rico's lower status. Even worse, the "special laws" for overseas areas weren't written until 30 years later, in 1865. Even then, their suggestions were never made into laws.

The Gloriosa Revolt in Spain in 1868, which removed Queen Isabel II from power, at first seemed to give Puerto Ricans more rights to be part of the Spanish government. The island elected seven representatives to the Cortes, and the Diputación Provincial was formed again. Plans were made to give the island more self-rule (autonomy).

But three things stopped this progress:

- First, the government in Spain was very unstable. Puerto Rico had five different governors between 1871 and 1874.

- Second, a short revolt in Puerto Rico called the Grito de Lares showed authorities that the island wasn't as calm as it seemed.

- Third, the Lares revolt happened at the same time as the Ten Years' War in Cuba. This made the Spanish government worried about giving self-rule to either Caribbean island.

In 1875, the old royal family was restored when Alfonso XII became king. Limited elections were allowed in Puerto Rico, but only people with a lot of property could vote. Real political parties also started to appear. The Partido Liberal Reformista wanted more self-rule for the island. The Partido Liberal Conservador wanted the island to be more connected to Spain's political system.

The issue of self-rule became very important in 1895 when the Cuban War of Independence began. In 1897, the Overseas Minister, with the Prime Minister's approval, took an unusual step. They wrote the Constitución Autonómica, which granted self-rule to the Caribbean islands.

This new government was to have "an Island Parliament, divided into two chambers, and one Governor-General, representing Spain, who would carry out his duties in its name." Elections for the parliament and local councils happened in early 1898. The island's legislature met for the first time in July, just eight days before the United States invaded the island. After Spain lost the war, the US took over Puerto Rico as a territory.

See also

In Spanish: Capitanía General de Puerto Rico para niños

In Spanish: Capitanía General de Puerto Rico para niños

- History of Puerto Rico

- Military history of Puerto Rico

- Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo

- List of governors of Puerto Rico