History of Puerto Rico facts for kids

The history of Puerto Rico started when the Ortoiroid people settled the island between 430 BC and AD 1000. When Christopher Columbus arrived in the New World in 1493, the main group of people living there were the Taínos. Sadly, the Taíno population greatly decreased in the 1500s because of new diseases brought by Europeans, harsh treatment by Spanish settlers, and wars.

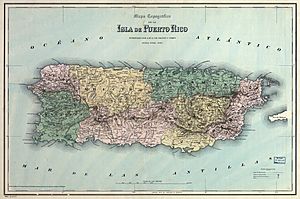

Puerto Rico, located in the northeastern Caribbean, was a very important part of the Spanish Empire. It was a key military base during many wars between Spain and other European countries in the 1500s, 1600s, and 1700s.

In 1593, Portuguese soldiers became the first guards at the San Felipe del Morro fortress in Puerto Rico. Some brought their families, and others married local women. Today, many Puerto Rican families have Portuguese last names. Puerto Rico, the smallest of the Greater Antilles islands, was a vital stop for ships traveling from Europe to Cuba, Mexico, Central America, and South America.

For most of the 1800s, until the Spanish–American War, Puerto Rico and Cuba were Spain's last two colonies in the New World. Spain tried to keep control of these islands by bringing in new settlers. The Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 offered free land to Europeans who would move to the islands, as long as they promised loyalty to Spain and the Roman Catholic Church.

In 1898, during the Spanish–American War, the United States took over Puerto Rico. The early 1900s were a time when Puerto Ricans worked hard to gain more democratic rights from the United States.

The Foraker Act of 1900 created a civilian government, ending military rule by American generals. A U.S. Supreme Court decision confirmed that the U.S. Constitution applied to Puerto Rico. The Jones Act of 1917 made Puerto Ricans U.S. citizens. This led to the creation of Puerto Rico's Constitution, which was approved in 1952. However, Puerto Rico's political status as a Commonwealth controlled by the United States is still a unique situation.

Contents

Early History of Puerto Rico

The first people to settle in Puerto Rico were the Ortoiroid people from South America. Some experts believe they arrived as early as 4000 years ago. In 1990, archaeologists found the remains of an Ortoiroid man on the island of Vieques, dating back to about 2000 BC. Later, the Saladoid people arrived from the same region between 430 and 250 BC.

Between the 7th and 11th centuries, the Arawak people settled the island. During this time, the Taíno culture grew and became the main culture by about 1000 AD. The Taíno people came from the Orinoco River basin in Venezuela and traveled to Puerto Rico by crossing the Lesser Antilles.

When Columbus arrived, about 30,000 to 60,000 Taíno people lived on the island. Their leader was the cacique (chief) Agüeybaná. They called their island "Borinquen," meaning "the great land of the valiant and noble Lord." The Taíno lived in small villages led by a cacique and found food by hunting, fishing, and gathering plants like cassava root and fruit. When the Spaniards arrived in 1493, the Taíno were already fighting with the Carib people, who were moving up the Antilles chain. The arrival of the Spanish marked the beginning of the end for the Taíno people. However, their culture still influences modern Puerto Rico. For example, musical instruments like maracas and güiro, the hammock, and words like Mayagüez, Arecibo, iguana, Caguas, and huracán (hurricane) are part of the Taíno legacy.

Spanish Rule (1493–1898)

Beginning of Spanish Colonization

On November 19, 1493, Christopher Columbus landed on the island during his second voyage and named it San Juan Bautista after Saint John the Baptist. The first European settlement, Caparra, was founded on August 8, 1508, by Juan Ponce de León. He was a lieutenant under Columbus and was greeted by the Taíno chief Agüeybaná. Ponce de León later became the island's first governor.

In 1509, the settlement was moved to a nearby islet with a good harbor, which was named Puerto Rico (meaning "Rich Port"). In 1511, a second town, San Germán, was started in the southwest. By the 1520s, the island became known as Puerto Rico, and the port became San Juan.

The Spanish settlers forced the native people to work for them. To try and stop this harsh treatment, Ferdinand II of Aragon issued the Burgos' Laws in 1512. These laws tried to protect the native people, regulating their work hours and ensuring they received care. However, in 1511, the Taínos revolted against the Spanish. Chief Urayoán, following a plan by Agüeybaná II, ordered his warriors to drown the Spanish soldier Diego Salcedo to see if the Spaniards were truly immortal. The revolt was quickly stopped by Ponce de León. Within a few decades, most of the native population died from diseases and violence. As a result, much of the Taíno culture, language, and traditions were lost.

The Roman Catholic Church also played a role in colonizing the island. In 1511, Pope Julius II created three dioceses in the New World, one in Puerto Rico. Alonso Manso became the first bishop to arrive in the Americas in 1513. He also established the first school of advanced studies in Puerto Rico in 1512.

African slaves were brought to the island starting in 1513 to replace the declining Taíno population. However, the number of slaves in Puerto Rico was much smaller compared to other Caribbean islands. The Caribs attacked Spanish settlements in 1514 and 1521 but were easily defeated.

European Threats and Fortifications

Many European countries tried to take control of the Americas from Spain. In 1528, the French attacked and burned the town of San Germán in Puerto Rico. They also destroyed other early settlements before the local militia forced them to leave. Only the capital, San Juan, remained.

Spain decided to protect its valuable possession. In 1532, they began building the first fortifications, like La Fortaleza (the Fortress), near the entrance to San Juan Bay. Later, massive defenses were built around San Juan, including Fort San Felipe del Morro and Fort San Cristóbal. These forts helped protect the island from attacks.

On November 22, 1595, the English privateer Sir Francis Drake tried to attack San Juan but could not defeat the strong forts. On June 15, 1598, the Royal Navy, led by George Clifford, 3rd Earl of Cumberland, landed troops and took control of the island for several months. However, they had to leave because many soldiers got sick with dysentery. Spain then sent new soldiers and a governor to rebuild San Juan.

More attacks happened in the 1600s and 1700s. In 1625, the Dutch attacked San Juan, but the Spanish successfully defended Fort San Felipe del Morro. The English tried to attack Arecibo in 1702 but failed. In 1797, the British tried again to conquer San Juan with a large invasion force, but the Spanish army successfully defended the city.

During these times, Puerto Rican society began to form. A census in 1765 showed a population of 44,883, with a small percentage of slaves. In 1786, the first complete history of Puerto Rico was published, describing the island's history and unique identity, including its music and culture. Puerto Ricans also fought in the American Revolutionary War in 1779, helping Spain defeat the British in several battles.

Changes in the 19th Century

The 1800s brought many political and social changes to Puerto Rico. In 1809, Spain, fighting against Napoleon, invited representatives from its colonies to a meeting. Ramón Power y Giralt became Puerto Rico's delegate. The Ley Power ("the Power Act") opened five ports for free trade and brought economic reforms. In 1812, the Cádiz Constitution was adopted, giving Puerto Ricans conditional citizenship.

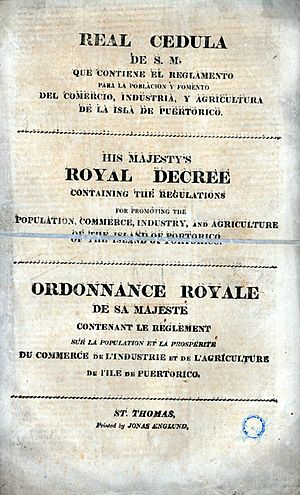

On August 10, 1815, the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815 was issued. This allowed foreigners, including French refugees, to come to Puerto Rico and opened the port to trade with other countries. This led to economic growth based on sugar, tobacco, and coffee. The decree also offered free land to anyone who promised loyalty to Spain and the Roman Catholic Church. Thousands of families from Europe, seeking better lives, moved to Puerto Rico. However, these gains in freedom were short-lived, as absolute power returned to Spain after Napoleon's fall.

In 1835, Queen María Cristina abolished the slave trade to Spanish colonies. In 1851, the Royal Academy of Belles Letters was founded, promoting education and literature.

In 1858, Samuel Morse brought wired communication to Latin America by setting up a telegraph system in Puerto Rico. He connected his son-in-law's hacienda to his house in Arroyo.

Minor slave revolts happened during this time. The most important was planned by Marcos Xiorro in 1821, though it was unsuccessful. He became a legend among slaves.

Struggle for Self-Rule

The late 1800s were marked by Puerto Rico's fight for self-rule. A census in 1860 showed a population of 583,308, with many people living in poverty. The economy suffered from high taxes and natural disasters. Spain also exiled or jailed anyone who asked for liberal reforms.

On September 23, 1868, hundreds of people in the town of Lares revolted against Spanish rule, seeking Puerto Rican independence. This event, known as the Grito de Lares ("Lares Uprising"), was planned by Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances and Segundo Ruiz Belvis. Although significant, the uprising was quickly stopped by Spanish authorities.

After the Grito de Lares, political and social reforms began. On June 4, 1870, the Moret Law was approved, giving freedom to some slaves. On March 22, 1873, slavery in Puerto Rico was officially abolished. In 1870, the first political groups formed: the Traditionalists, who wanted to be part of Spain's political system, and the Autonomists, who wanted more self-rule for Puerto Rico.

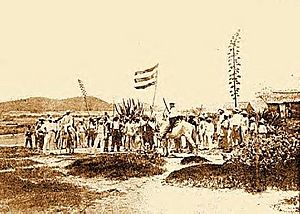

In 1897, Antonio Mattei Lluberas and other independence leaders in Yauco organized another uprising, known as the "Intentona de Yauco". This was the first time the current Puerto Rican flag was raised on the island. However, Spanish authorities quickly stopped this uprising.

Puerto Rico came close to achieving self-rule on November 25, 1897, when the Carta Autonómica (Charter of Autonomy) was approved in Spain. This charter gave the island political and administrative self-rule. It allowed a governor appointed by Spain (who could veto laws) and a partially elected parliament. The new government officially began on February 9, 1898. Local lawmakers could set their own budget and taxes. However, this autonomous government did not last long.

The Invasion of 1898

In 1890, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, a U.S. Navy thinker, wrote a book arguing for a strong navy and the need for colonies in the Caribbean for coaling stations and defense. By 1896, the U.S. Navy had plans for military operations in Puerto Rican waters.

On March 10, 1898, Dr. Julio J. Henna and Robert H. Todd, leaders of the Puerto Rican section of the Cuban Revolutionary Party, contacted U.S. President William McKinley. They hoped he would include Puerto Rico in the planned intervention in Cuba and provided information about Spanish military forces on the island.

The Spanish–American War began in late April 1898. The American plan was to take Spanish colonies in the Atlantic (Puerto Rico and Cuba) and the Pacific (the Philippines and Guam). On May 12, a U.S. fleet bombarded San Juan. On July 18, General Nelson A. Miles, commander of U.S. forces, received orders to sail to Puerto Rico.

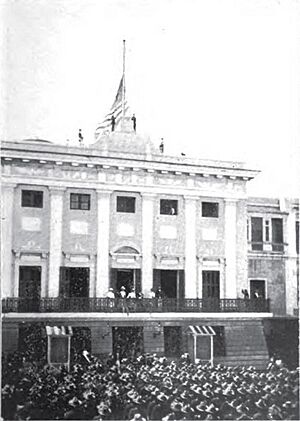

On July 25, 1898, General Nelson Miles landed unopposed at Guánica, on the southern coast of the island, with the first American troops. Although there was some resistance in the southern and central regions, the island was under United States control by the end of August.

On August 12, peace agreements were signed in Washington. On December 10, 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed. Spain gave up all claims to Cuba, and ceded Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States. Spain also sold the Philippines to the U.S. for $20 million. General John R. Brooke became the first United States military governor of Puerto Rico.

United States Rule (1898–Present)

Military Government and Early Changes

After the Treaty of Paris, Puerto Rico came under U.S. military control. The island's name was changed to Porto Rico (it went back to Puerto Rico in 1932), and the currency changed from the Puerto Rican peso to the United States dollar. New freedoms were given, such as freedom of assembly, speech, press, and religion. An eight-hour day was set for government workers. A public school system and the U.S. Postal service were started. Roads and bridges were improved.

New political groups formed, like the Partido Republicano and the American Federal Party. Both supported Puerto Rico becoming part of the United States. Local sugar planters hoped U.S. rule would help them sell their sugar in the North American market.

In August 1899, two hurricanes, the 1899 San Ciriaco hurricane and another, hit the island. About 3,400 people died, and thousands lost their homes and jobs. The economy was badly hurt, with millions of dollars lost from sugar and coffee plantations.

The Foraker Act of 1900

The military government in Puerto Rico was short-lived. On April 2, 1900, the U.S. Congress passed the Foraker Act. This act created a civilian government and allowed free trade between Puerto Rico and the United States. The government included a governor appointed by the U.S. president, an executive council, and a legislature. The first civil governor, Charles Herbert Allen, started his term on May 1, 1900.

The act also created a court system and allowed Puerto Rico to send a Resident Commissioner to represent them in Congress. The Department of Education was formed, and teaching was done in English, with Spanish as a special subject. However, both Spanish and English were official languages.

Economic and Social Modernization

The American plan focused on building modern infrastructure like roads, ports, electricity, telephones, and hospitals. They also worked to improve agriculture.

From 1898 to 1945, sugar mills became large plantations. Sugar, tobacco, and cigar factories grew quickly, attracting U.S. attention. By 1914, coffee production had declined. The sugar industry grew with U.S. corporate investment, modernizing sugar processing mills.

The U.S. also formed a Tobacco Trust, which controlled cigarette and cigar production. However, the industry later declined due to export issues.

The U.S. administrators also focused on developing a modern school system. However, teaching entirely in English caused concerns about losing Puerto Rican culture. Many teachers, parents, and intellectuals resisted, wanting to preserve the island's Hispanic language and traditions. This strong opposition led to the failure of U.S. language policies in schools. By the 1940s and 1950s, Spanish became the main language of instruction in public schools and the University of Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico's farming economy changed to focus mainly on sugar. American sugar companies had an advantage over local owners because they could get loans with lower interest rates. This, along with tariffs, forced many local sugar plantation owners to sell their land to larger companies.

Political Developments

As Puerto Rico's economy changed, people wanted new political status. Leaders like Luis Muñoz Rivera and José de Diego helped create many political parties. These parties had different goals: some wanted Puerto Rico to become a U.S. state, others wanted it to be a U.S. territory (commonwealth), and some wanted complete independence.

In 1909, the Foraker Act was changed by the Olmsted Amendment, which put Puerto Rican affairs under a U.S. executive department. In 1914, the first Puerto Rican officers were appointed to the Executive Cabinet, giving Puerto Ricans a majority in the Council for the first time. These efforts, along with speeches by Resident Commissioner Muñoz Rivera, led to the Jones Act of 1917.

The Jones Act of 1917

The Jones Act replaced the Foraker Act. It was approved by the U.S. Congress on December 5, 1916, and signed into law on March 2, 1917. This act made Puerto Rico an "organized but unincorporated" United States territory, similar to a colony. Puerto Ricans were also given a limited U.S. citizenship, meaning they could not vote for the U.S. President while living on the island.

The Act also allowed for conscription (drafting soldiers) on the island, sending 20,000 Puerto Rican soldiers to the U.S. Army during World War I. The Act divided government powers into three branches: executive (appointed by the U.S. President), legislative, and judicial. The legislative branch, with a senate and house of representatives, was elected by the Puerto Rican people. A bill of rights was also created, and elections were to be held every four years.

On October 11, 1918, a powerful earthquake hit Puerto Rico, causing a tsunami. It caused great damage and loss of life, especially in Mayagüez. About 116 people died from the earthquake and 40 from the tsunami.

Some politicians wanted Puerto Rico to become a U.S. state, while others wanted independence. Amid this debate, a nationalist group emerged. The Partido Nacionalista de Puerto Rico (Puerto Rican Nationalist Party) was founded on September 17, 1922. This party supported independence and organized protests. In 1924, Pedro Albizu Campos joined the party and later became its president in 1930. He strongly promoted anti-colonial ideas.

In the 1930s, the Nationalist Party, led by Pedro Albizu Campos, did not gain enough support in elections. Conflicts grew between their supporters and the authorities. On October 23, 1935, a shooting occurred at the University of Puerto Rico-Río Piedras campus, resulting in the deaths of four Nationalists and one bystander. In response, Nationalists killed Colonel E. Francis Riggs, the U.S.-appointed Police Chief, in San Juan. Pedro Albizu Campos was later arrested and convicted of conspiring against the American government.

On March 21, 1937, a peaceful march organized by the Nationalist Party in Ponce was met with police gunfire. This event, known as the "Ponce massacre", resulted in 20 unarmed people being killed and many more wounded.

Establishment of the Commonwealth

After World War II, many Puerto Ricans moved to the mainland United States, especially to New York City. This was due to economic problems from the Great Depression and job opportunities in the U.S. armed forces and companies.

In 1946, President Truman appointed Jesús T. Piñero as governor, the first Puerto Rican to hold that position. On June 10, 1948, Piñero signed the infamous "Ley de la Mordaza" (Gag Law). This law made it illegal to display the Puerto Rican flag, sing a nationalist song, or campaign for independence.

The U.S. Congress passed an act allowing Puerto Ricans to elect their own governor. The first elections were held on November 2, 1948, and Luis Muñoz Marín became the first democratically elected Governor on January 2, 1949.

On July 4, 1950, President Harry S. Truman signed Public Act 600, allowing Puerto Ricans to write their own constitution and establish their own government. This act renamed the political body the "Commonwealth of Puerto Rico." Once in office, Muñoz Marín did not pursue independence, which angered some of his supporters.

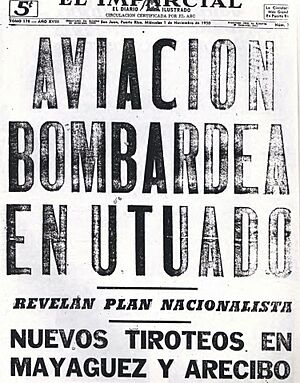

On October 30, 1950, a group of Puerto Rican nationalists, led by Pedro Albizu Campos, staged several attacks, known as the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party revolts of the 1950s. The most notable was the Jayuya Uprising. Two days later, two Nationalists from New York tried to assassinate President Harry S. Truman at Blair House. These actions led Muñoz to crack down on nationalists.

In February 1952, the Constitution of Puerto Rico was approved by voters. That same year, the Flag of Puerto Rico could be publicly displayed again after being illegal since 1948. In March 1954, four Nationalists fired guns in the U.S. House of Representatives to protest the lack of Puerto Rican independence, wounding several people.

On July 23, 1967, the first vote (plebiscite) on Puerto Rico's political status was held. Voters chose to continue as a Commonwealth (60.4%). Other votes were held in 1993 and 1998, and both times, the Commonwealth status was upheld. In 2012, a majority voted to reject the current status and chose statehood, but this vote was controversial.

The New Progressive Party was formed under Luis A. Ferré's leadership, campaigning for Puerto Rico to become the 51st state of the U.S. Luis A. Ferré was elected governor in 1968, the first time a pro-statehood governor won.

Puerto Rico continues to debate its political status. Even though it has its own Constitution since 1952, it remains a U.S. territory. This unique status continues to be a major topic in Puerto Rican society.

Moving Toward Statehood

More votes on Puerto Rico's political status were held in 1993 and 1998. In all these votes, remaining a Commonwealth was chosen, though support for statehood has grown.

The Puerto Rican status referendum, 2012 showed that 54% of voters wanted a new status, and of those, 61.1% chose statehood. This was the most successful vote for statehood supporters. However, because many blank ballots were cast, the U.S. Congress decided to ignore the vote.

The Puerto Rican status referendum, 2017 offered two choices: Statehood or Independence/Free Association. If the majority chose the latter, a second vote would decide between full independence or an associated free state status with a special political agreement with the U.S.

Governor Ricardo Rosselló strongly supported statehood, believing it would help the economy and solve the "colonial dilemma." Benefits of statehood could include more federal funds, the right to vote in presidential elections, and higher Social Security and Medicare benefits.

Any changes to Puerto Rico's status require action by the United States Congress.

Economic History

Coffee was a major industry before the 1940s. Its production grew in the central mountains after 1855 due to cheap land, many workers, and a growing market. However, it declined after 1897 and ended with a major hurricane in 1928 and the Great Depression in the 1930s. While coffee declined, sugar and tobacco became more important due to the large U.S. market.

After 1898, Puerto Rico's economy and society modernized with new roads, ports, railroads, telegraph lines, and public health programs. The high infant death rate decreased steadily because of basic public health efforts.

In the 1920s, Puerto Rico's economy boomed. A big increase in sugar prices brought money to farmers. This led to improvements in the island's infrastructure, with new schools, roads, and bridges. More private wealth was seen in new homes, and banking and transport grew with commerce and agriculture.

This period of wealth ended in 1929 with the start of the Great Depression. Agriculture was the main part of the economy, and industry and trade slowed down. Problems worsened when Hurricane San Ciprián hit the island on September 27, 1932, causing many deaths and millions of dollars in damage.

Under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, the Puerto Rican Reconstruction Administration was created. Funds were provided for new housing, transportation, and other improvements. In 1938, a new federal minimum wage law was passed, which caused many textile factories to close because they could not afford to pay the higher wages.

Since 1945

After World War II, many young people moved to U.S. cities for work and sent money back to their families. In 1950, Washington introduced Operation Bootstrap, which greatly boosted economic growth from the 1950s to the 1970s. This led to Puerto Rico becoming one of the wealthiest economies in Latin America, though it still had to import most of its food.

Operation Bootstrap, supported by Governor Muñoz Marín, encouraged U.S. investors to open factories in Puerto Rico. They received tax breaks and could sell their products in U.S. markets without import duties. Lower wages on the island were also an incentive. This program changed Puerto Rico from an agricultural society to an industrial one.

In 2005, protests led to the closure of the Roosevelt Roads Naval Station, causing a loss of 6,000 jobs and $300 million in income each year.

In 2006, Puerto Rico's credit rating was lowered, leading to financial measures to cut government spending and increase revenue, including a 7% sales tax.

Today, Puerto Rico is a popular tourist spot and a major center for pharmaceuticals, manufacturing, and finance in the Caribbean.

In early 2017, Puerto Rico faced a serious government-debt crisis, with $70 billion in debt. The island had been in a recession for a decade, with high poverty and unemployment rates. The government was struggling to pay its debts.

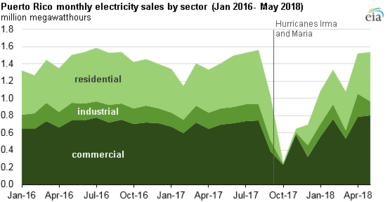

In September 2017, Hurricane Maria destroyed most of the island's power grid, leaving millions without electricity for months. This disaster and the slow recovery caused over 100,000 people to move to the U.S. mainland, hurting the island's economy and making the financial crisis worse.

In May 2018, after Hurricane Maria severely damaged Puerto Rico's water system, a report found that 70% of the population was living with water that did not meet U.S. safety laws.

Images for kids

-

Aftermath in Mayaguez of the 1918 earthquake.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Puerto Rico para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Puerto Rico para niños