Pedro Albizu Campos facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pedro Albizu Campos

|

|

|---|---|

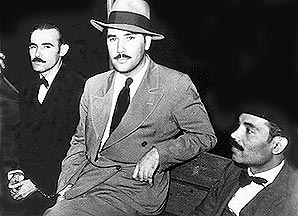

Pedro Albizu Campos during his years at Harvard University, 1913–1919

|

|

| Born | September 12, 1891 |

| Died | April 21, 1965 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | Puerto Rican |

| Alma mater | University of Vermont Harvard University |

| Organization | Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

| Spouse(s) | Laura Meneses |

Pedro Albizu Campos (born September 12, 1891 – died April 21, 1965) was a lawyer and political leader from Puerto Rico. He was a very important person in the movement for Puerto Rico to become independent. He could speak six languages, which means he was a polyglot. He studied at Harvard Law School and earned the best grades in his class. This meant he should have given the main speech at graduation. However, because of his mixed race background, his professors delayed his final exams. This stopped him from graduating on time. While at Harvard University, he also supported Ireland's fight for freedom.

Albizu Campos led the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico from 1930 until he passed away in 1965. People called him El Maestro (The Teacher) because he was a great speaker. He spent 26 years in prison. This was because he tried to change the United States government's control over Puerto Rico.

In 1950, he planned and called for armed uprisings in several cities in Puerto Rico. After these events, he was found guilty and sent to prison again. He died in 1965, soon after being released from federal prison. He had suffered a stroke. There has been some disagreement about the medical care he received in prison.

Contents

Who Was Pedro Albizu Campos?

Early Life and School Days

Pedro Albizu Campos was born on September 12, 1891, in Machuelo Abajo, a part of Ponce, Puerto Rico. His mother, Juana Campos, was a domestic worker of African heritage. His father, Alejandro Albizu Romero, was a merchant from a Basque family. This family had moved from Spain and lived in Venezuela for a while. Pedro's uncle was the famous composer Juan Morel Campos. His cousin was the educator Dr. Carlos Albizu Miranda. Pedro's mother died when he was young. His father did not recognize him as his son until Pedro was at Harvard University.

Pedro went to Ponce High School. This was a public school mainly for the city's white students. In 1912, he won a scholarship to study Chemical Engineering at the University of Vermont. The next year, in 1913, he moved to Harvard University to continue his studies.

Joining the Army

When World War I started, Albizu Campos joined the United States Infantry. He became a Second Lieutenant in the Army Reserves. He was sent to Ponce to help organize the town's Home Guard. Later, he was called to serve in the regular Army. He went to Camp Las Casas for more training. After his training, he joined the 375th Infantry Regiment. At that time, the U.S. Army was segregated. This meant Puerto Ricans who looked African were put into all-black units. Officers were usually classified as white. Albizu Campos was considered black.

Albizu Campos was honorably discharged from the Army in 1919. He left with the rank of First Lieutenant. However, his experiences with racism in the military changed his views. He became a strong supporter of Puerto Rican independence.

Harvard University Years

In 1919, Albizu went back to Harvard University. He was chosen to be president of the Harvard Cosmopolitan Club. He met students and leaders from around the world. These included Subhas Chandra Bose, an Indian nationalist, and the Hindu poet Rabindranath Tagore. He became interested in India's fight for freedom. He also helped set up centers in Boston to support Irish independence. Through this work, Albizu Campos met the Irish leader Éamon de Valera. He later helped write the constitution for the Irish Free State. While at Harvard University, he also helped start the university's Knights of Columbus group with other Catholic students.

Albizu graduated from Harvard Law School in 1921. At the same time, he was studying literature, philosophy, chemical engineering, and military science at Harvard College. He was very good at languages. He spoke six modern languages: English, Spanish, French, German, Portuguese, and Italian. He also knew two old languages: Latin and ancient Greek.

After law school, Albizu Campos was offered important jobs. These included working for the U.S. Supreme Court and a job with the U.S. State Department. He was also offered a high position at a U.S. farming company and a teaching job at the University of Puerto Rico.

On June 23, 1921, Albizu returned to Puerto Rico after graduating from Harvard Law School. But he did not have his law diploma yet. He had faced unfair treatment from one of his professors. This professor delayed two of Albizu Campos's final exams. Albizu was about to graduate with the highest grades in his entire law class. He was supposed to give the main speech at the graduation ceremony. The professor delayed his exams so he could not finish his work. This was to avoid the "embarrassment" of a Puerto Rican student being the top graduate.

Albizu Campos left the United States. He took and passed the two exams in Puerto Rico. In June 1922, he received his law degree by mail. He passed the bar exam and became a lawyer in Puerto Rico on February 11, 1924.

His Family Life

In 1922, Albizu married Dr. Laura Meneses. She was a Peruvian biochemist he had met at Harvard University. They had four children: Pedro, Laura, Rosa Emilia, and Héctor.

Puerto Rico's History and Independence

Puerto Rico was controlled by the Spanish Empire for almost 400 years. In 1898, it finally gained some self-rule with a special document called a Carta de Autonomía (Charter of Autonomy). This document was signed by the Spanish Prime Minister and approved by the Spanish government.

However, just a few months later, the United States took control of the island. This happened as part of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Spanish–American War. Many people did not agree with this takeover. Over the years, they joined together to form the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. They believed that Spain could not give the United States something it no longer owned.

Years later, in 1913, Charles Herbert Allen became president of the American Sugar Refining Company. He had been the first civilian U.S. governor of Puerto Rico. This company was the biggest of its kind in the world. It was later renamed Domino Sugar. According to historian Federico Ribes Tovar, Charles Allen used his time as governor to gain control over Puerto Rico's entire economy.

The Nationalist Party Begins

Nationalist activists wanted Puerto Rico to be free from foreign banks, large plantation owners, and United States rule. So, they started to organize in Puerto Rico.

In 1919, José Coll y Cuchí formed the Nationalist Association of Puerto Rico in San Juan. He wanted to work for independence. They got permission from the government to bring back the remains of Ramón Emeterio Betances, a Puerto Rican hero, from Paris, France.

By the 1920s, two other groups working for independence had formed. These were the Nationalist Youth and the Independence Association of Puerto Rico. On September 17, 1922, these three groups joined together. They formed the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. Coll y Cuchi became president, and José S. Alegría became vice president.

In 1924, Pedro Albizu Campos joined the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. He was elected vice president. In 1927, Albizu Campos traveled to many countries. He visited Santo Domingo, Haiti, Cuba, Mexico, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela. He was looking for support for the Puerto Rican Independence movement from other Latin American countries.

In 1930, Albizu and José Coll y Cuchí, the party president, disagreed on how to run the party. Albizu Campos felt that Coll y Cuchí was too friendly with the "enemy." Because of this, Coll y Cuchí left the party. He and some of his followers went back to the Union Party. On May 11, 1930, Albizu Campos was elected president of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. He also started the first Women's Nationalist Committee in Vieques, Puerto Rico.

After becoming president, Albizu said: "I never believed in numbers. Independence will instead be achieved by the intensity of those that devote themselves totally to the Nationalist ideal." He started a new campaign with the slogan, "La Patria es valor y sacrificio" (The Homeland is valor and sacrifice). This meant showing pride in their nation through bravery and sacrifice. Albizu Campos connected his idea of sacrifice with his Catholic faith.

Leading the Nationalist Party

A Doctor's Controversial Letter

In 1932, Albizu shared a letter that caused a big stir. The letter was written by Dr. Cornelius P. Rhoads. He was an American doctor working at the Rockefeller Institute. Albizu said that Dr. Rhoads had killed Puerto Rican patients at a hospital in San Juan as part of his medical research. Albizu Campos had found an unsent letter written by Rhoads to a friend.

In his letter, Rhoads complained about a job appointment. He also wrote some very offensive things about Puerto Ricans. He said he had "killed off eight" patients and that he could "eradicate the whole population" if he stayed longer. He also said that Puerto Ricans were "the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate and thievish lot of sub-humans" he had ever seen. Rhoads later said he wrote the letter in anger after his car was vandalized. He claimed it was meant as a "joke" for his friend.

Albizu sent copies of the letter to many important groups. These included the League of Nations, the Pan American Union, and the American Civil Liberties Union. He also sent it to newspapers, embassies, and the Vatican. He used this as a chance to speak out against the United States' control over Puerto Rico. He wrote: "The colonial system is the cause of all these evils."

This caused a big scandal. Dr. Rhoads had already gone back to New York. The governor of Puerto Rico and other officials investigated the cases of over 250 patients treated by Rhoads. The Rockefeller Foundation also did its own investigation. They concluded that Rhoads had treated his patients properly. When this issue was looked at again in 2002, no evidence of medical mistreatment was found. However, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) found the letter so offensive that they removed Rhoads' name from a special award.

Early Efforts for Independence

The Nationalist Party did not win many votes in the 1932 election. But they kept working to unite the island for independence. In 1933, Albizu Campos led a strike against a power company. He said the company had a monopoly on the island. The next year, he worked as a lawyer for sugar cane workers. He helped them in a lawsuit against the U.S. sugar industry.

The Nationalist movement grew stronger after some of its members were killed by police. This happened during unrest at the University of Puerto Rico in 1935. It was called the Río Piedras Massacre. The police were led by Colonel E. Francis Riggs, a former U.S. Army officer. After this, Albizu decided the Nationalist Party would not take part in elections. He said they would not participate until the United States ended its control.

In 1936, Hiram Rosado and Elías Beauchamp killed Colonel Riggs. They were members of the Cadets of the Republic, the Nationalist youth group. After they were arrested, they were killed without a trial at police headquarters in San Juan.

In 1937, police also killed marchers and bystanders at a parade. This event is known as the Ponce massacre. Nationalists believed these events showed how much violence the United States was willing to use to keep control of Puerto Rico. Historians say that this harsh treatment, especially during the Great Depression, was because U.S. businesses were making huge profits from controlling the island.

First Time in Prison

After these events, on April 3, 1936, a federal grand jury charged Albizu Campos and several other Nationalist leaders. They were accused of sedition and other crimes against the government.

The government said the Nationalists created the Cadets, calling them the "Liberating Army of Puerto Rico." They claimed the Cadets were taught military tactics to overthrow the U.S. government. The first jury had seven Puerto Ricans and five Americans. They could not agree on a decision, voting 7 to 5 for not guilty. So, the judge allowed a new trial. The second jury had ten Americans and two Puerto Ricans. This jury found the defendants guilty.

In 1937, a group of lawyers tried to appeal the case. But the court upheld the guilty verdict. Albizu Campos and the other Nationalist leaders were sent to the Federal prison in Atlanta.

In 1939, U.S. Congressman Vito Marcantonio strongly criticized the trial. He called it a "frame-up" and a "black page in American history." He said Albizu's jury was unfair because the prosecutor had chosen people who already disliked the defendants. Marcantonio argued that Puerto Ricans should have the same freedoms as Americans. He called for a full and immediate pardon for Albizu.

In 1943, Albizu Campos became very sick. He was moved to the Columbus Hospital in New York. He stayed there until almost the end of his sentence. In 1947, after eleven years in prison, Albizu was released. He returned to Puerto Rico. Soon after, he began preparing for a fight against the U.S. plan to make Puerto Rico a "commonwealth."

The "Gag Law" and Uprisings

Passage of the Gag Law

In 1948, the Puerto Rican Senate passed Law 53, also known as the Ley de la Mordaza (Gag Law). At that time, most Senate seats were held by the Popular Democratic Party (PPD). Luis Muñoz Marín was in charge of the Senate.

The U.S.-appointed governor of Puerto Rico, Jesús T. Piñero, signed this bill into law on June 10, 1948. It was similar to the anti-communist Smith Law in the United States.

This law made it illegal to own or show a Puerto Rican flag anywhere, even in your own home. It limited speaking against the U.S. government or for Puerto Rican independence. It also stopped people from printing, publishing, selling, or showing any material meant to harm the government. Organizing any group with such a goal was also forbidden. Anyone found guilty could face ten years in prison, a $10,000 fine, or both.

Dr. Leopoldo Figueroa, a member of the Puerto Rican Statehood Party, spoke out against the law. He said it was unfair and went against the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. This amendment guarantees Freedom of Speech. Figueroa pointed out that since Puerto Ricans were U.S. citizens, they should have these constitutional protections.

Uprisings Across the Island

Pedro Albizu Campos was jailed again after the Nationalist revolts on October 30, 1950. These revolts, known as the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party Revolts of the 1950s, happened in several Puerto Rican cities and towns. They were against United States rule. Some of the most well-known revolts included the Jayuya uprising, where Nationalists led by Blanca Canales held the town for three days. There was also the Utuado uprising, which ended in the "Utuado Massacre." Another event was the attack on La Fortaleza (the Puerto Rican governor's mansion) during the Nationalist attack of San Juan.

On October 31, police officers and National Guardsmen surrounded a barbershop in Santurce. They thought Nationalists were inside and started shooting. The only person in the shop was Albizu Campos's barber, Vidal Santiago Díaz. Santiago Díaz fought alone against the attackers for three hours. He was shot five times, including once in the head. The entire gunfight was broadcast live on the radio. Everyone on the island heard it. Overnight, Santiago Díaz became a hero in Puerto Rico.

During the revolt, Albizu was at the Nationalist Party headquarters in Old San Juan, which was also his home. He was with Juan José Muñoz Matos, Doris Torresola Roura, and Carmen María Pérez Roque. Police and National Guard surrounded the building and fired their weapons without warning. Doris Torresola was shot and wounded. She was carried out during a ceasefire. Alvaro Rivera Walker, a friend of Pedro Albizu Campos, managed to reach him. He stayed with Albizu Campos until the next day when they were attacked with gas. Rivera Walker then surrendered by raising a white towel. All the Nationalists, including Albizu, were arrested.

Another Arrest and Attack on Blair House

On November 1, 1950, Nationalists Oscar Collazo and Griselio Torresola attacked Blair House in Washington, D.C. President Harry S. Truman was staying there while the White House was being fixed. During the attack, Torresola and a policeman, Private Leslie Coffelt, were killed.

Because of this attack, Pedro Albizu Campos's home was immediately attacked. After a shootout with the police, Albizu Campos was arrested. He was sentenced to eighty years in prison. Over the next few days, 3,000 people who supported independence were arrested across the island.

The Capitol Shooting and More Arrests

Albizu was pardoned in 1953 by Governor Luis Muñoz Marín. But the pardon was taken back the next year. This happened after the 1954 United States Capitol shooting incident. In this event, four Puerto Rican Nationalists, led by Lolita Lebrón, opened fire from the gallery of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C..

Even though he was in poor health, Pedro Albizu Campos was arrested again. This was after Lolita Lebrón, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Andrés Figueroa Cordero, and Irvin Flores opened fire on members of the 83rd Congress on March 1, 1954. They did this to get worldwide attention for Puerto Rican independence.

Ruth Mary Reynolds, an American Nationalist, helped defend Albizu Campos and the four Nationalists involved in the shooting. She did this with the help of the American League for Puerto Rico's Independence.

Final Years and Legacy

His Health and Passing

While in prison, Albizu's health got worse. He claimed that he was being experimented on with radiation in prison. He said he could see colored rays hitting him. When he wrapped wet towels around his head to block the radiation, the prison guards made fun of him. They called him El Rey de las Toallas (The King of the Towels).

Officials suggested that Pedro Albizu Campos was mentally ill. However, other prisoners at La Princesa prison, like Francisco Matos Paoli, Roberto Díaz, and Juan Jaca, said they also felt the effects of radiation on their bodies.

Dr. Orlando Daumy, a radiologist and head of the Cuban Cancer Association, came to Puerto Rico to examine him. After examining Albizu Campos, Dr. Daumy concluded three things:

- The sores on Albizu Campos were caused by radiation burns.

- His symptoms matched those of someone who had received a lot of radiation.

- Wrapping himself in wet towels was the best way to lessen the effects of the rays.

The FBI investigated any doctors who planned to visit and check on Pedro Albizu Campos. Dr. Nacine Hanoka was one of them. An FBI memo to J. Edgar Hoover asked the Miami office to find out if Dr. Hanoka had visited Puerto Rico and to check for any "subversive information" about him.

In 1956, Albizu had a stroke in prison. He was moved to San Juan's Presbyterian Hospital under police guard.

On November 15, 1964, when he was very close to death, Pedro Albizu Campos was pardoned by Governor Luis Muñoz Marín. He died on April 21, 1965. More than 75,000 Puerto Ricans joined a procession to accompany his body for burial in the Old San Juan Cemetery.

What is His Legacy?

Pedro Albizu Campos's legacy is still talked about by those who supported him and those who did not. Lolita Lebrón called him "Puerto Rico's most visionary leader." Many nationalists see him as "one of the island's greatest patriots of the 20th century." Social scientist Juan Manuel Carrión wrote that "Albizu still represents a forceful challenge to the very fabric of [Puerto Rico's] colonial political order." His supporters say that his actions helped bring about positive changes in Puerto Rico. These included better working conditions for farmers and workers. He also helped people understand the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. His followers believe his legacy is one of great sacrifice for building the Puerto Rican nation and resisting colonial rule. His critics say he "failed to attract and offer concrete solutions to the struggling poor and working class people and thus was unable to spread the revolution to the masses."

Albizu Campos also helped bring back the public celebration of the Grito de Lares and its important symbols.

FBI Files on Albizu Campos

In the 2000s, files from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) were released. These files, made public under the Freedom of Information Act, showed that the FBI watched Albizu and other Puerto Ricans for decades. This surveillance was coordinated between FBI offices in San Juan, New York, Chicago, and other cities. These documents, some as recent as 1965, can be viewed online.

Honoring Pedro Albizu Campos

Pedro Albizu Campos has been the subject of many books and articles. He has also been honored in the United States and Puerto Rico in many ways:

- In Chicago, a special high school is named the Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School.

- La Casa de Don Pedro in Newark, New Jersey, is named after him.

- In New York City, the Campos Plaza Community Center and a housing project in Manhattan are named after him.

- Also in New York City, Public School 161 in Harlem is named after him.

- In Puerto Rico, streets in most towns are named after him.

- In Ponce, there is a Pedro Albizu Campos Park and a lifesize statue in his memory. Every September 12, his birthday, his contributions to Puerto Rico are remembered at this park.

- In Salinas, there is a "Plaza Monumento Don Pedro Albizu Campos." This plaza has a 9-foot statue dedicated to him. It was opened on January 11, 2013, the birthday of Eugenio María de Hostos, another Puerto Rican who fought for independence. This monument is unique because it was built by a local government that has a different political view (statehood) than Albizu Campos.

- In 1993, Chicago alderman Billy Ocasio supported a statue of Albizu Campos in Humboldt Park. He compared Albizu Campos to American leaders like Patrick Henry, Chief Crazy Horse, John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and W. E. B. Du Bois.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pedro Albizu Campos para niños

In Spanish: Pedro Albizu Campos para niños

- Puerto Ricans in World War I

- San Juan Nationalist revolt

- Puerto Rican Independence Party

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |