Grito de Lares facts for kids

Quick facts for kids El Grito de Lares |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

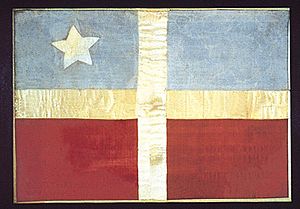

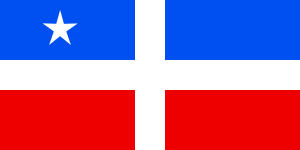

Flag of El Grito de Lares. |

|||||

|

|||||

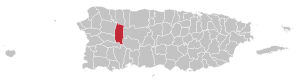

El Grito de Lares (which means The Cry of Lares) was the first big rebellion against Spain in Puerto Rico. It's also called the Lares uprising or revolt. This important event was planned by Ramón Emeterio Betances and Segundo Ruiz Belvis. It started on September 23, 1868, in the town of Lares, which is how it got its name. The rebellion quickly spread to other groups across the island.

Contents

Why the Revolt Happened

In the 1860s, Spain was fighting in different places, like a war with Peru and Chile. They also had to deal with slave revolts in Cuba. At the same time, Puerto Rico and Cuba were facing tough economic times. Spain was charging very high taxes on goods that were imported and exported. They needed this money to pay for their soldiers in the Dominican Republic.

Many people in Puerto Rico wanted independence from Spain. Others just wanted fairer rules. The Spanish government often jailed or exiled these people. However, in 1865, Spain tried to calm things down. They created a "board of review" to hear complaints from their overseas provinces. This board, called the Junta Informativa de Reformas de Ultramar, met in Madrid.

Puerto Rico's representatives were chosen by a vote. This was one of the first times people in Spain's colonies could vote. Segundo Ruiz Belvis, who wanted independence, was elected. This worried the governor of Puerto Rico, as most people on the island did not support independence.

The Puerto Rican delegates, led by José Julián Acosta, were frustrated. Most of the board members were from mainland Spain. They voted against almost every idea the Puerto Ricans had, even ending slavery. However, Acosta did manage to convince them that slavery could end in Puerto Rico without hurting the economy. Later, slavery was indeed abolished in Puerto Rico.

But other ideas, like giving Puerto Rico more self-rule, were rejected. Also, they couldn't limit the governor's huge power over the island. When the delegates returned to Puerto Rico, they met with local leaders in 1865.

Ramón Emeterio Betances, who wanted independence, was at this meeting. He had been exiled by Spain twice. After hearing about all the rejected ideas, Betances said, "Nadie puede dar lo que no tiene" (You can't give away what you don't own). He meant that Spain wouldn't give Puerto Rico or Cuba any real changes.

Betances then suggested a full rebellion across the island to declare independence. Many people at the meeting agreed with him. Because of the lack of political and economic freedom, and the strict rules from Spain, an armed rebellion was soon planned.

The Rebellion Begins

Planning the Uprising

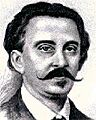

The Lares uprising, or Grito de Lares, was a carefully planned event. The word Grito means a "cry for independence." Similar "cries" happened in Brazil, Mexico, and Cuba. In Puerto Rico, Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances and Segundo Ruiz Belvis started the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico in January 1868. They were in exile in the Dominican Republic.

Betances wrote several Proclamas (statements). These statements criticized Spain's control over Puerto Ricans and called for an immediate uprising. These messages spread across the island, and local groups started to organize. One important document was Los Diez Mandamientos de los hombres libres (The Ten Commandments of Free Men). It was based on the French Revolution's ideas about human rights.

Around the same time, poet Lola Rodríguez de Tió wrote new, patriotic words for the tune of La Borinqueña, which is now Puerto Rico's national anthem.

Eduvigis Beauchamp Sterling, who managed the revolution's money, gave Mariana Bracetti the materials to make the Revolutionary Flag of Lares. This flag had a white Latin cross in the middle. The two bottom corners were red, and the two top corners were blue. A white star was placed in the top left blue corner. The white cross means hope for the homeland, the red squares mean the blood of heroes, and the white star in the blue square means liberty and freedom.

Secret groups of the Revolutionary Committee were set up in Puerto Rico by Mathias Brugman, Mariana Bracetti, and Manuel Rojas. These groups included people from all parts of society: landowners, merchants, professionals, farmers, and even slaves. Most were criollos (Spaniards born on the island).

The Revolutionary Committee chose twelve of its members as generales (generals). These included:

- Manuel Rojas, who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Liberation Army.

- Mathías Brugman, General of Division.

- Juan de Mata Terreforte, General of Division.

- Mariana Bracetti, who made the flag, was also a key leader.

The bad economy, slavery, and Spain's harsh rules pushed the people toward rebellion. The strongest support for the movement came from towns in the mountains on the western side of the island.

The uprising was originally planned for September 29 in Camuy. However, Spanish authorities found out about the plan. A captain overheard rebels talking about poisoning bread rations. Documents about the meeting were found, and some leaders were arrested.

Also, a ship full of weapons for the rebels, provided by the Dominican government, was stopped by Spanish authorities in the Danish West Indies. With their plans discovered and weapons gone, the leaders decided to start the revolution earlier, without telling Betances.

Declaring the Republic of Puerto Rico

The leaders decided to start their revolution in Lares on September 23. About 400 to 600 rebels gathered at Manuel Rojas's farm near Lares. Led by Rojas and Juan de Mata Terreforte, these rebels, who were not well-trained or armed, reached the town around midnight. They took over the city hall and looted stores owned by Spanish mainlanders and government offices. These people were seen as enemies of the homeland and were taken prisoner.

The rebels then went into the town's church and placed the revolutionary flag of Lares on the main altar. This was a sign that the revolution had officially begun. At 2:00 am, the Republic of Puerto Rico was declared in the church, with Francisco Ramírez Medina as president. The revolutionaries also promised freedom to any slaves who joined them.

President Ramírez Medina appointed government officials, including:

- Francisco Ramírez Medina, President

- Aurelio Méndez, Minister of the Interior

- Manuel Rojas, Commander in Chief of the Liberation Army

Fight at San Sebastián

The next day, September 24, the rebel forces moved to take over the nearby town of San Sebastián del Pepino. But the Puerto Rican militia, with troops from San Juan, Mayagüez, Ponce, and other towns, surprised them with strong resistance. The rebels were confused and at a disadvantage without the weapons Betances was supposed to send.

The rebels had to retreat back to Lares. On the governor's orders, the militia quickly rounded them up, and the uprising was over.

Trials and Freedom

About 475 rebels, including Dr. José Gualberto Padilla, Manuel Rojas, and Mariana Bracetti, were put in prison in Arecibo. They faced harsh treatment there. On November 17, a military court sentenced all the prisoners to death for treason.

However, in Madrid, Eugenio María de Hostos and other important Puerto Ricans spoke up for the prisoners. They convinced President Francisco Serrano, who had just led his own revolution in Spain. To calm the situation in Puerto Rico, the new governor, José Laureano Sanz, declared a general amnesty (forgiveness) in early 1869. All the prisoners were released. But leaders like Betances, Rojas, and others were sent into exile.

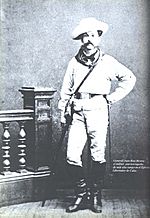

As a young man, Juan Ríus Rivera became friends with Betances and joined the independence movement. He was part of a revolutionary group in Mayagüez. Even though he was studying law in Spain and didn't take part in the Lares uprising, he followed Caribbean politics closely. When he heard the revolt failed, he went to the United States and offered his help to the Cuban Revolutionary Junta. Juan Ríus Rivera later went to Cuba and became a high-ranking general in the Cuban Liberation Army.

Mariana Bracetti moved to Añasco, where she passed away in 1903.

What Happened Next

Even though the revolt didn't achieve full independence, it made a big difference. The Spanish government gave Puerto Rico more political freedom.

In the years after the Grito, there were smaller protests and fights with Spanish authorities in towns like Las Marías, Adjuntas, and Utuado.

Juan de Mata Terreforte, who fought with Manuel Rojas, was exiled to New York City. He joined the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee and became its Vice-President. Terreforte and the committee members used the Flag of Lares as Puerto Rico's flag until 1892. That's when the current flag design, which looks like the Cuban flag, was created and adopted by the committee.

Celebrations

While there isn't an official holiday for El Grito de Lares, the day is celebrated every September in the Plaza de Recreo de la Revolución in Lares barrio-pueblo.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Grito de Lares para niños

In Spanish: Grito de Lares para niños

- Military history of Puerto Rico

- Ramón Emeterio Betances

- Puerto Rican Nationalist Party Revolts of the 1950s

- Puerto Rican Independence Party

- Puerto Rican Nationalist Party