Argentine War of Independence facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Argentine War of Independence |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish American wars of independence | |||||||

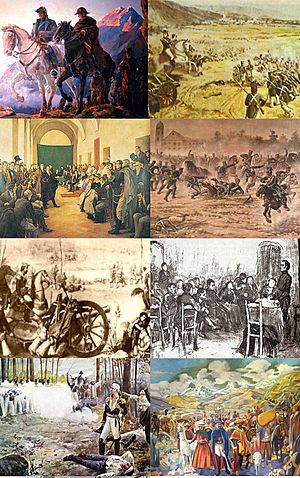

From top and left: Crossing of the Andes, Battle of Salta, 22 May 1810 Open Cabildo, Battle of San Lorenzo, Battle of Suipacha, 1813 Assembly, Shooting of Liniers, Jujuy Exodus. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Patriots: Republiquetas |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Manuel Belgrano José de San Martín Martín Miguel de Güemes † Juan José Castelli José Gervasio Artigas William Brown Carlos María de Alvear |

Bernardo de Velasco José Manuel de Goyeneche Joaquín de la Pezuela Pedro Antonio Olañeta † Santiago de Liniers Vicente Nieto |

||||||

The Argentine War of Independence was a big fight that happened from 1810 to 1818. It was fought by Argentinian forces, led by heroes like Manuel Belgrano and José de San Martín. They fought against forces loyal to the Spanish Empire, who wanted to keep control. On July 9, 1816, a special meeting in San Miguel de Tucumán declared Argentina's independence from Spain.

Contents

Why the War Started: The Background

The land we now call Argentina was once part of a large Spanish area called the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. Its main city was Buenos Aires, where the Spanish ruler, called a viceroy, lived. Modern-day Uruguay, Paraguay, and Bolivia were also part of this area. They also started wanting their own freedom during this time.

The viceroyalty was huge, and it was hard for people in different areas to communicate. The richest parts were in Upper Peru (now Bolivia). Cities like Salta and Córdoba were closer to Upper Peru than to Buenos Aires. Mendoza in the west had stronger ties with Chile.

People in Buenos Aires and Montevideo (who were rivals) were more connected to Europe. This meant they heard about new ideas and economic changes faster. Paraguay, however, was very isolated from everyone else.

People and Power: Criollos vs. Peninsulares

Most important jobs in the Spanish government were given to people from Spain. These people were called peninsulares. They often didn't care much about problems in South America. This made people born in Latin America, called Criollos, feel left out.

Even though both groups were considered Spanish, Criollos felt that Peninsulares had too much power. New ideas from the American Revolution and French Revolution made Criollos want changes. Spain also stopped its colonies from trading with other countries. This rule hurt the economy of the viceroyalty.

British Attacks and Local Power

Buenos Aires became very military-focused after the British invasions of the Río de la Plata. In 1806, the British took Buenos Aires, but Santiago de Liniers and forces from Montevideo helped free it. Fearing another attack, everyone in Buenos Aires who could fight, even slaves, joined military groups.

A new British attack in 1807 captured Montevideo but was defeated in Buenos Aires. The viceroy, Rafael de Sobremonte, was removed by the Criollos during this time. The Regiment of Patricians, a local military group, became very powerful in Buenos Aires politics.

Spain's king, Ferdinand VII, was captured by the French. His sister, Carlota Joaquina, wanted to rule the Americas. But she didn't get support from the Spanish Americans or the British. Javier de Elío created a local government in Montevideo. Martín de Álzaga tried to do the same in Buenos Aires, but local soldiers stopped him. Spain then sent a new viceroy, Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros.

The May Revolution: A New Government

By 1810, the war in Spain was getting worse. French armies had taken over most of Spain. The Spanish government in Seville was shut down. Many people fled to Cádiz, the last part of Spain still fighting. They formed a new ruling group called the Council of Regency.

When news of this reached Buenos Aires, it started the May Revolution. Many people thought Viceroy Cisneros no longer had the right to rule. They asked for a special meeting, an open cabildo, to decide what to do. The military supported this request, and Cisneros had to agree.

The meeting decided to remove Cisneros and replace him with a new government group, a junta. But they tried to keep Cisneros as the president of this new junta. People protested more, and the junta had to resign right away. A new one, the Primera Junta, was formed.

Buenos Aires asked other cities to accept the new Junta and send representatives. At first, cities like Córdoba, Montevideo, Paraguay, and Upper Peru resisted the Junta. Santiago de Liniers tried to gather an army to fight Buenos Aires. Montevideo had a strong navy.

The Council of Regency in Spain declared Buenos Aires a rebel city. They made Montevideo the new capital of the viceroyalty. At first, the May Revolution wasn't about full independence. Both sides claimed to be loyal to King Ferdinand VII. They just disagreed on who should rule while the king was away.

Fighting for Freedom: The Armed Conflict

The Primera Junta sent armies to different parts of the viceroyalty. They wanted to get support for the new government and keep control. The battles helped decide which areas would become part of the new United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. The first fights were mostly in the north (Upper Peru) and east (Banda Oriental). Later, the fighting moved west to Chile.

Early Battles and Campaigns

The first armies sent by Buenos Aires went to Córdoba and Paraguay. Córdoba was where former Viceroy Santiago de Liniers was trying to start a counter-revolution. Paraguay did not accept the new government in Buenos Aires.

Liniers' army in Córdoba left him before fighting. He tried to escape to Upper Peru to join the royalist army. But the patriot army, led by Colonel Francisco Ortiz de Ocampo, captured Liniers. Ocampo was supposed to execute them but sent them to Buenos Aires instead. So, he was replaced by Juan José Castelli. On August 26, Castelli executed the prisoners and led the army north.

- First Upper Peru campaign (1810–1811)

Castelli sent General Antonio González Balcarce into Upper Peru. He lost a battle at battle of Cotagaita. Castelli sent more soldiers, and they won their first big victory at the battle of Suipacha. This gave Buenos Aires control over Upper Peru. Royalist generals were captured and executed.

Castelli wanted to attack the Viceroyalty of Peru, but Buenos Aires said no. The armies waited near the border. Then, the royalists attacked and defeated Castelli at the Battle of Huaqui. The patriot forces scattered. However, local patriot fighters in Upper Peru kept the royalists from moving further south.

- Paraguay campaign (1810–1811)

Another army, led by Manuel Belgrano, went towards Paraguay. They won a small battle at Battle of Campichuelo. But they were badly defeated at the battles of Paraguarí and Tacuarí. This campaign failed militarily. However, Paraguay later declared its own independence, inspired by Argentina.

- First Banda Oriental campaign (1811)

New Attacks and Key Victories

The losses in Paraguay and Upper Peru led to a new government in Buenos Aires in September 1811. This new group, called the Triumvirate, decided to try again in Upper Peru. They put Manuel Belgrano in charge of the Army of the North. They also appointed José de San Martín, a skilled soldier who had just arrived from Spain, to create a new cavalry unit called the Regiment of Mounted Grenadiers.

- Second Upper Peru campaign (1812–1813)

General Manuel Belgrano was the new commander. A large royalist army was invading. Belgrano used a "scorched-earth" tactic. He ordered people to leave Jujuy and Salta and burn everything behind them. This stopped the enemy from getting supplies or taking prisoners. This event is known as the Jujuy Exodus.

Belgrano went against orders and fought the royalists at Tucumán, winning a great victory. He then defeated them again at the Battle of Salta. The royalist army had to surrender. Belgrano showed mercy and released them. But later, the patriot army lost battles in Upper Peru at Vilcapugio and Ayohuma. They had to retreat.

- Second Banda Oriental campaign (1812–1814)

In early 1812, fighting started again between Buenos Aires and Montevideo. José Rondeau began a second siege of Montevideo. The royalists tried to break the siege but were defeated at the Battle of Cerrito.

The Spanish navy tried to attack towns on the Uruguay river. On January 31, 1813, Spanish troops landed near San Lorenzo. But on February 3, San Martín's Granaderos unit completely defeated them. The Battle of San Lorenzo stopped further Spanish raids. San Martín was promoted to general.

The Granaderos also helped change the government in Buenos Aires. A new Triumvirate was formed, which was more serious about independence. This new Triumvirate called a national assembly to declare independence. The assembly first replaced the Triumvirate with a single leader, the Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. Gervasio Antonio de Posadas was chosen for this role.

Posadas quickly created a navy. William Brown was made its chief commander. On May 14, 1814, Brown's small navy fought the Spanish fleet and defeated it. This victory secured the port of Buenos Aires. It also led to the fall of Montevideo on June 20, 1814, as the city could no longer be supplied.

The Road to Independence

With Montevideo captured, the Spanish threat from the east was gone. William Brown was made an admiral. Carlos María de Alvear became the new Supreme Director. But Alvear was not popular with the troops and was quickly replaced by Ignacio Álvarez Thomas. Álvarez Thomas then tried to make Alvear general of the Northern Army, but the soldiers stayed loyal to José Rondeau.

- Third Alto Perú campaign (1815)

In 1815, the Northern Army, led by José Rondeau, started another attack in Upper Peru. They did not have official support and faced problems. They also lost help from the Salta army, led by Martín Miguel de Güemes. After losing battles at Venta y Media and Sipe-Sipe, the northern parts of Upper Peru were lost to the United Provinces. However, the Spanish army could not move further south because of the strong resistance from Güemes's local fighters in Salta.

The failure of this campaign made people in Europe think the revolution was over. Also, King Ferdinand VII was back on the Spanish throne in 1813. So, the United Provinces urgently needed to decide their political future.

On July 9, 1816, a meeting of representatives from different provinces happened at the Congress of Tucumán. They declared the Independence of the United Provinces in South America from the Spanish Crown. They also started planning a national Constitution.

The Army of the Andes (1814–1818)

In 1814, General José de San Martín was in charge of the Army of the North. But he soon realized that attacking Upper Peru again would lead to another defeat. He came up with a new plan: attack the Spanish in Peru by going through Chile first. He was inspired by a British officer who said this was the only way.

San Martín became the Governor of the Province of Cuyo. There, he prepared his new army, the Army of the Andes. This army was made up of patriots from the United Provinces and Chile.

In early 1817, San Martín led his army across the Andes mountains into Chile. They won a major victory at the battle of Chacabuco on February 17, 1817. They took Santiago de Chile. San Martín refused to become governor of Chile. He wanted to focus on his main goal: capturing Lima. Bernardo O'Higgins became the new leader of Chile. In December 1817, Chile held a vote to decide its independence.

However, Spanish forces still fought in southern Chile, with help from the Mapuche people. In early 1818, more Spanish soldiers arrived from Peru. San Martín again used "scorched-earth" tactics, ordering people to leave Concepción. On February 18, 1818, Chile declared its independence from Spain.

On March 18, 1818, the Spanish surprised the Argentine-Chilean army. The patriot army had to retreat to Santiago, losing many soldiers. In the confusion, people thought O'Higgins had been killed, causing panic. O'Higgins, injured, gave full command to San Martín. Then, on April 5, 1818, San Martín won a decisive victory at the Battle of Maipú. The Spanish retreated and never launched another major attack on Santiago.

The Chile campaign is usually seen as the end of the Argentine War of Independence. The next actions by the army into Peru were done under the Chilean government, not Argentina's. However, defensive battles continued in northern Argentina until the 1825 Battle of Ayacucho. This battle finally ended the Spanish threat from Upper Peru.

Remembering the Fight: Annual Commemoration

Día de la Revolución de Mayo (May Revolution Day) on May 25 is a national holiday in Argentina. It celebrates the creation of the Primera Junta, which was a very important event in Argentina's history. The events of the week leading up to this day are called Semana de Mayo (May Week).

See Also

In Spanish: Guerra de la Independencia Argentina para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de la Independencia Argentina para niños

- Spanish American wars of independence

- Rise of the Republic of Argentina

- United Provinces of the Río de la Plata

- Timeline of the Argentine War of Independence

- Argentine Irredentism

Images for kids

-

The May Revolution made the viceroy step down. A new government, the Primera Junta, took his place.

-

San Martín wrapped in the flag.