First Upper Peru campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First Upper Peru campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Argentine War of Independence | |||||||

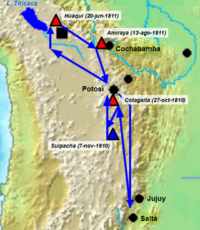

Path of the Military campaign. The blue mark is for patriot victories (Suipacha), the red mark for royalist victories (Cotagaita, Huaqui and Amiraya) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Patriots | Royalists | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Juan José Castelli Francisco Ortiz de Ocampo Antonio González Balcarce Juan José Viamonte |

José Manuel de Goyeneche Vicente Nieto |

||||||

The First Upper Peru campaign was an important military effort during the Argentine War of Independence. It happened in 1810 and was led by Juan José Castelli. The main goal was to spread the ideas of the May Revolution from Buenos Aires into Upper Peru (which is now modern Bolivia).

The campaign started with some wins, like the Battle of Suipacha. There was also a local uprising in Cochabamba that helped the cause. However, the campaign eventually faced a big defeat at the Battle of Huaqui. This loss meant that Upper Peru went back under the control of the Royalists (those loyal to the Spanish King). Later, other leaders like Manuel Belgrano and José Rondeau tried similar campaigns, but they also failed. Upper Peru was finally freed much later by Antonio José de Sucre, who came from the North with Simón Bolívar's army.

Contents

Why the Campaign Started

The Spark of Independence

The Spanish King, Ferdinand VII, was captured during a war in Europe called the Peninsular War. This made people in many Spanish colonies wonder who should rule them. A group in Seville, Spain, took charge, saying they were governing for the absent king.

However, many people in the colonies felt they had the right to govern themselves. This led to small revolutions in places like Chuquisaca and La Paz in Upper Peru. But these early attempts were quickly stopped by Spanish authorities.

Buenos Aires Takes Action

The May Revolution in Buenos Aires was more successful. It removed the Spanish viceroy (a high-ranking official) from power. The new government, called the Primera Junta, decided to send military groups to secure control over different areas. One group went to Paraguay, and another, the "Army of the North," headed to Upper Peru.

Before reaching Upper Peru, this army had to deal with a counter-revolution in Córdoba. This uprising was organized by the former viceroy, Santiago de Liniers. The initial commander, Ortiz de Ocampo, was replaced by Juan José Castelli because he didn't follow orders to deal with the rebels strictly.

How the Campaign Unfolded

Castelli Takes Command

When Castelli arrived in Córdoba, he wasn't very popular. But in San Miguel de Tucumán, he was welcomed. In Salta, he struggled to get enough soldiers, supplies, and money. Castelli took full political control of the expedition. He replaced Ortiz de Ocampo with Colonel Antonio González Balcarce.

Castelli learned that Cochabamba had revolted to support the new government in Buenos Aires. However, royalist forces from La Paz were threatening them. He also found out that a royalist army led by Goyeneche was moving towards Jujuy.

Early Battles and Victories

Balcarce, who had moved towards Potosi, was first defeated by a royalist leader named Nieto at the Battle of Cotagaita. Castelli quickly sent more soldiers and cannons to help Balcarce. With these extra forces, Balcarce won a major victory at the Battle of Suipacha. This win allowed the patriots to take control of almost all of Upper Peru without much resistance. One of the soldiers sent to help was Martín Miguel de Güemes, who later became a famous leader in Salta.

Controlling Upper Peru

In Villa Imperial, a very rich city in Upper Peru, local leaders asked Goyeneche to leave their territory. He did, as he didn't have enough soldiers to fight. Castelli was welcomed in Potosí. He made people swear loyalty to the new government and demanded the surrender of royalist generals like Francisco de Paula Sanz and José de Córdoba y Rojas. These generals, along with Vicente Nieto, were later removed from power.

Bernardo Monteagudo, who had been in jail for his role in an earlier revolution, escaped and joined Castelli's army. Castelli, knowing Monteagudo's background, made him his secretary.

New Laws and Ideas

Castelli set up his government in Chuquisaca. He began to change things across the region. He planned to reorganize the famous Potosi mines and reform the University of Charcas.

Most importantly, Castelli declared an end to native slavery in Upper Peru. He gave native people political rights, making them equal to the criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the Americas). He also stopped new religious buildings from being built. This was to prevent religious groups from forcing native people into servitude. He allowed free trade and gave land to former workers. These new rules were published in Spanish, Guarani, Quechua, and Aymara. He also started bilingual schools.

The first anniversary of the May Revolution was celebrated in Tiahuanaco with local Indian chiefs. Castelli honored the ancient Incas and encouraged people to fight against the Spanish. However, Castelli knew that many rich families in Upper Peru only supported his army out of fear, not true belief.

Plans and Problems

In November 1810, Castelli suggested a bold plan to the government in Buenos Aires. He wanted to cross the Desaguadero River, which was the border, and take control of Peruvian cities like Puno, Cuzco, and Arequipa. He believed this would weaken Lima, the main royalist stronghold. But his plan was considered too risky and was rejected. Castelli was told to stick to the original orders.

Support for Castelli began to drop. This was mainly because he treated native people so well and because the church strongly opposed him. The church attacked Castelli through his secretary, Bernardo Monteagudo, who was known for his public atheism (not believing in God). Both royalists and some leaders in Buenos Aires compared Castelli and Monteagudo to Maximilien Robespierre, a leader during the French Revolution's "Reign of Terror."

Castelli also ended the mita system in Upper Peru. This was a forced labor system that had been used for centuries. This idea was shared by Mariano Moreno, another important leader, but Moreno had already been removed from the government in Buenos Aires. Without Castelli in Buenos Aires to help, arguments between Moreno and Saavedra (another leader) got worse. The government asked Castelli to be less extreme, but he continued with his plans.

Some officers who supported Saavedra even planned to kidnap Castelli and send him back to Buenos Aires for trial. They wanted to give command of the army to Juan Jose Viamonte. However, Viamonte refused to go along with the plan. When Castelli learned about Moreno's fate, he wrote to his supporters, asking them to come to Upper Peru. He hoped that after defeating Goyeneche, they could all march back to Buenos Aires. But his letter was intercepted, and his supporters in Buenos Aires had already been removed from power.

The Defeat

Broken Truce

The government in Buenos Aires had told Castelli not to advance into the Viceroyalty of Peru. This was like a temporary peace as long as Goyeneche wasn't attacked. Castelli tried to make this a formal agreement, which would mean the royalists recognized the new government. Goyeneche agreed to a 40-day truce (a temporary stop to fighting) to wait for orders from Lima. But he used this time to make his army stronger.

On June 19, even though the truce was still in effect, a royalist group attacked some patriot positions. Castelli declared the truce broken and announced war on Peru.

The Battle of Huaqui

The royalist army crossed the Desaguadero River on June 20, 1811. This started the Battle of Huaqui. The patriot army waited near Huaqui, between the plains of Azapanal and Lake Titicaca. The left side of the patriot army, led by Diaz Velez, faced the main royalist forces. The center was attacked by soldiers led by Pio Tristan.

Many patriot soldiers who had been recruited in Upper Peru gave up or ran away. Many recruits from La Paz even switched sides during the battle. Juan José Viamonte, a Saavedrist officer, played a big part in the defeat by refusing to join the fight.

Aftermath of the Defeat

Even though the Army of the North didn't lose a huge number of soldiers, they were very discouraged and disorganized. The people of Upper Peru turned away from them and welcomed the royalists back. So, the army had to quickly leave those provinces. However, the strong resistance in Cochabamba stopped the royalists from moving further towards Buenos Aires.

Castelli moved to Quirbe and soon received orders to return to Buenos Aires for a trial. But these orders were quickly changed. Castelli was to be confined (kept) in Catamarca, and Saavedra himself would take charge of the Army of the North. However, Saavedra was removed from power as soon as he left Buenos Aires. The new government, called the First Triumvirate, then ordered Castelli to return.

Once in Buenos Aires, Castelli found himself alone politically. The Triumvirate and a newspaper accused him of the defeat at Huaqui. They wanted to punish him to set an example. His former supporters were either with the Triumvirate or couldn't do much to help him. Castelli suffered from tongue cancer during his long trial, which made it harder for him to speak. He died in October 1812, before his trial was finished.

See also

In Spanish: Primera expedición auxiliadora al Alto Perú para niños

In Spanish: Primera expedición auxiliadora al Alto Perú para niños