Juan José Castelli facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Juan José Castelli

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Committee member of the Primera Junta | |

| In office 25 May 1810 – 9 June 1811 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 July 1764 Buenos Aires, Viceroyalty of Peru |

| Died | 12 October 1812 (aged 48) Buenos Aires, United Provinces of the Río de la Plata |

| Resting place | San Ignacio Church |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party | Carlotism, Patriot |

| Spouse | María Rosa Lynch |

| Alma mater | University of Chuquisaca |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1810–1811 |

| Commands | Army of the North |

| Battles/wars | First Upper Peru campaign |

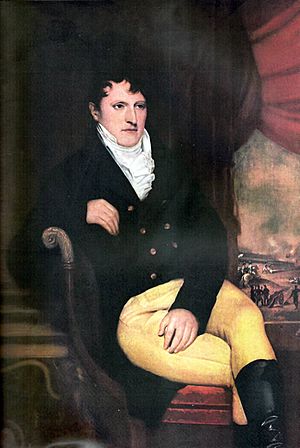

Juan José Castelli (born July 19, 1764 – died October 12, 1812) was an Argentine lawyer. He was a key leader in the May Revolution, which started the Argentine War of Independence. He also led a military campaign in Upper Peru, which is now Bolivia.

Castelli was born in Buenos Aires. He went to school at the Real Colegio de San Carlos in Buenos Aires and Monserrat College in Córdoba. He became a lawyer after studying at the University of Charcas in Upper Peru. His cousin, Manuel Belgrano, helped him get involved in the government of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata.

Castelli, Belgrano, Nicolás Rodríguez Peña, and Hipólito Vieytes secretly planned a revolution. They wanted to replace the old system of kings with new ideas from the Age of Enlightenment. Castelli was a main leader for the patriots in Buenos Aires during the May Revolution. This revolution ended with the removal of the Spanish ruler, Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros. Castelli is often called the "Speaker of the Revolution" because of his important speech on May 22, 1810. This speech happened during a special meeting called an open cabildo in Buenos Aires.

Castelli became a member of the Primera Junta, which was the first independent government. He was sent to Córdoba to stop a rebellion led by Santiago de Liniers. Castelli succeeded and ordered the execution of Liniers and his supporters. He then worked to set up a new government in Upper Peru (modern-day Bolivia). His goal was to free the native people and African slaves. In 1811, Castelli signed a truce with the Spanish in Upper Peru. However, the Spanish broke the truce and surprised the Army of the North. This led to a big defeat for the Argentines at the Battle of Huaqui on June 20, 1811. When Castelli returned to Buenos Aires, the new government, the First Triumvirate, put him in prison for losing the battle. Castelli died soon after from tongue cancer.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Castelli was born in Buenos Aires in 1764. He was the first of eight children. His father, Ángel Castelli Salomón, was a doctor from Venice. His mother, Josefa Villarino, was related to Manuel Belgrano. Castelli was taught by the Jesuits for a short time before they were forced to leave. He then attended the Real Colegio de San Carlos in Buenos Aires.

It was common for one child in a family to become a priest. Juan José was chosen for this path. He went to study at Colegio Monserrat, which was part of the University of Córdoba. He read books by thinkers like Voltaire and Diderot, and especially Jean-Jacques Rousseau's The Social Contract. These books shared new ideas about freedom and government.

Castelli studied with many people who later became important in South America. These included Saturnino Rodríguez Peña, Juan José Paso, Manuel Alberti, and Manuel Martínez de Rozas. He focused on philosophy and religion. But when his father died in 1785, he decided not to become a priest. He didn't feel it was his true calling.

His mother wanted him to study in Spain, but Castelli chose to study law at the University of Chuquisaca in Upper Peru (now Bolivia). There, he learned about the French Revolution and the new ideas of the Age of Enlightenment. He also learned about the 1782 Rebellion of Túpac Amaru II and how native people were treated unfairly. This experience greatly influenced his future actions in Upper Peru. Before returning to Buenos Aires, he visited Potosí and saw how slaves were forced to work in the mines.

Castelli returned to Buenos Aires and started his own law firm. He represented the University of Córdoba and his uncle, Domingo Belgrano Peri. Through his friends, he also met Nicolás Rodríguez Peña and Hipólito Vieytes. In 1794, Castelli married María Rosa Lynch. They had seven children. Like many important Argentines of his time, he was a freemason.

In 1798, Castelli bought a large farm in what is now the Núñez neighborhood of Buenos Aires. He moved there in 1808. His neighbors included important figures like Cornelio Saavedra, Juan Larrea, and Miguel de Azcuénaga. On his farm, he grew crops and had a brick factory.

Early Political Involvement

Intellectuals in the viceroyalty secretly shared copies of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This important document came from the French Revolution in 1789. Meanwhile, Castelli's cousin, Manuel Belgrano, returned from Europe. He became the Perpetual Secretary of the new Consulate of Commerce of Buenos Aires.

Belgrano and Castelli shared similar ideas. They both disliked Spain's trade monopoly and believed in the rights of native people. Belgrano tried to make Castelli his assistant at the Consulate. But Spanish merchants strongly opposed this. Castelli's appointment was delayed until 1796. Belgrano often took time off due to illness and wanted Castelli to take over if he resigned.

There was similar opposition in 1799 when Castelli was elected to the Buenos Aires Cabildo (city council). Merchants connected to the port of Cádiz rejected him. This conflict lasted a year. Finally, a local merchant, Cornelio Saavedra, wrote a letter supporting Castelli. Viceroy Avilés officially confirmed Castelli's position in May 1800. However, Castelli turned down the job because he was too busy with his work at the consulate. This was seen as an insult by powerful Spanish merchants.

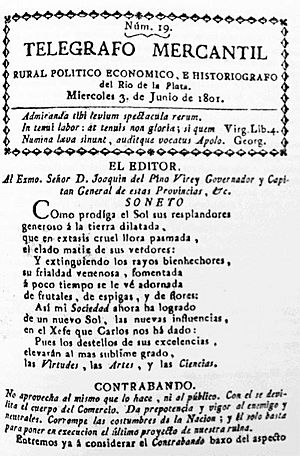

Castelli and Belgrano supported projects by Francisco Cabello y Mesa. He proposed creating a "Patriotic, Literary and Economic Society" and publishing a newspaper. This newspaper, the first in Buenos Aires, was called Telégrafo Mercantil. Both projects didn't last long. The society was never formed, and the newspaper was closed. Castelli, Cabello, and Belgrano worked on the Telegraph. It was the first newspaper to talk about the idea of a "fatherland" and call the local people "Argentines."

Soon after, Hipólito Vieytes started a new newspaper, the Agriculture, Trade and Industry Weekly. Castelli was part of its staff. They met to discuss ways to improve farming, remove trade limits, and develop industries. The newspaper also published stories about American leaders like Benjamin Franklin.

British Invasions

Castelli met an Irishman named James Florence Burke. Burke told Castelli that the British government supported ideas to free Latin American colonies from Spanish rule. Castelli didn't know that Burke was also a spy. Burke formed a secret group called the "party of independence." Castelli and others from Vieytes's newspaper joined.

Burke was eventually discovered by Viceroy Rafael de Sobremonte and forced to leave. Castelli moved to his farm in Núñez. The secret group continued its meetings. In June 1806, Castelli's mother died. While he was still in mourning, the city learned that the British had landed in Quilmes.

The "party of independence" was surprised by the invasion. The British promised to respect religion, property, and trade, but didn't mention independence. Castelli and his group met with the British leader, Viscount William Carr Beresford. They asked if the promises of independence were still valid. Beresford gave unclear answers. He said he had no instructions and needed new orders because the British Prime Minister had recently died.

Castelli felt the British wouldn't keep Burke's promises. He resigned from his position to avoid swearing loyalty to Britain. Santiago de Liniers soon recaptured Buenos Aires. But Saturnino Rodríguez Peña helped Beresford escape. He hoped Beresford could influence a second British invasion to bring about reforms. However, the second British invasion also didn't mention independence. Castelli then chose to fight against his former allies.

After successfully defending the city in 1807, the local criollos (people of Spanish descent born in the Americas) gained more political power. There was a disagreement between the new Viceroy, Santiago de Liniers, and the Buenos Aires Cabildo, led by Martín de Álzaga. Both tried to get the criollos to support them. Álzaga didn't accuse Rodríguez Peña of helping Beresford escape. Liniers kept the criollo military groups armed.

Carlotism and Sovereignty

In 1807, Napoleon invaded Spain, starting the Peninsular War. King Charles IV of Spain gave up his throne to his son Ferdinand VII. But Napoleon captured Ferdinand and made his own brother, Joseph Bonaparte, king of Spain. This event is known as the abdications of Bayonne.

The Spanish people formed local governments called Juntas to fight against the French. Soon, the Junta Central of Seville claimed to be the highest authority over Spain and its colonies. This situation encouraged Princess Charlotte of Spain, who was the sister of the captured King Ferdinand VII, to claim she should rule the Spanish American colonies.

Castelli and Álzaga secretly planned to remove Liniers and create a local government Junta, like those in Spain. However, most local people and the head of the Patricians Regiment, Cornelio Saavedra, didn't agree with this plan. Manuel Belgrano suggested supporting Princess Charlotte's plans instead. Castelli and other criollos supported this idea. Belgrano, who believed in having a king, thought this was the best way to gain independence from Spain.

On September 20, 1808, Castelli wrote a letter to Charlotte. It was signed by Antonio Beruti, Hipólito Vieytes, Belgrano, and Nicolás Rodríguez Peña. But Charlotte rejected their support. The independence group wanted a constitutional monarchy (a king with limited power) led by Charlotte. But she wanted to keep the power of an absolutist monarchy (a king with total power). So, she reported the letter and had Diego Paroissien arrested. Paroissien, who had letters for the criollos, was accused of betraying the king. Castelli became his lawyer.

Castelli won Paroissien's freedom. He argued that the Spanish American lands belonged personally to the King of Spain, not to Spain as a colony. He said that if the King was not there, then the power should return to the people. Castelli argued that neither the Council of Regency nor any other power in Spain had authority over Spanish America without the rightful King. He successfully argued that offering the regency to the King's sister was not treason. Instead, it was a legal political idea that the Spanish American people should decide on, without Spain's interference.

On January 1, 1809, Martín de Álzaga led a rebellion against Liniers in Plaza de Mayo. Some criollos, like Mariano Moreno, hoped this would lead to independence. But most did not. The military groups loyal to Liniers defeated the rebels. Castelli supported Liniers, accusing Álzaga of wanting independence. Even though Castelli also wanted independence and to remove Liniers, he opposed Álzaga. Álzaga wanted to keep Spanish-born people in power over the criollos. Álzaga was defeated, and the criollos gained more power.

A new viceroy, Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros, arrived in July to replace Liniers. The independence group couldn't agree on what to do next. Castelli suggested creating a governing Junta, but not led by the Spanish. Belgrano still wanted to make Charlotte regent of a constitutional monarchy. Rodríguez Peña suggested a military takeover. They finally agreed with Cornelio Saavedra to wait for a better chance.

May Revolution

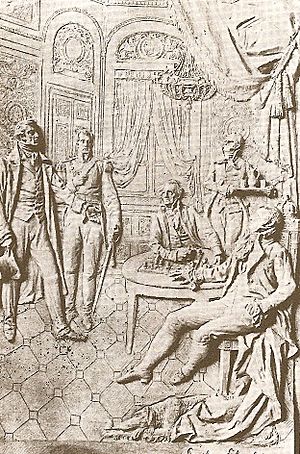

When news arrived that the Junta of Seville in Spain had fallen, Castelli and Belgrano's group led the events of the May Revolution. Castelli and Saavedra were the most important leaders. They first rejected a plan to remove Cisneros in a coup d'état. After many talks, they decided to ask for an open cabildo, which was an emergency meeting for the people.

Castelli and Belgrano talked with the city's mayor, Juan de Lezica, and the lawyer, Julián de Leiva. They convinced them, but still needed Cisneros's permission. Castelli and Rodríguez went to his office. Earlier, Cornelio Saavedra had told Cisneros that the Patricians Regiment would not support him. Saavedra argued that since the Junta of Seville, which had appointed Cisneros, no longer existed, he had no right to be viceroy.

Cisneros was angry when Castelli and Rodríguez arrived, armed and without an appointment. They spoke firmly and demanded an immediate answer about the open cabildo. After a short private talk, Cisneros agreed. As they left, Cisneros asked about his safety. Castelli replied, "Lord, Your Excellency and your family are among Americans, and this should make you feel safe." After the meeting, they returned to Rodríguez Peña's house to tell their supporters the news.

Castelli is known as the "Speaker of the Revolution" because of his important role during "May week." People who were there said he was very active. He negotiated with the Cabildo and visited the Fort many times until the viceroy gave in. At the same time, he held secret meetings with other criollos at Rodríguez Peña's house to plan their actions. He also encouraged the criollo militias at their barracks. Cisneros himself, when writing to the Council of Regency, called Castelli "the most interested one in the novelty," meaning in the revolution.

The open cabildo was held on May 22, 1810. They debated if the viceroy should stay in power and, if not, who should replace him. Bishop Benito Lue y Riega said Cisneros should continue. He argued that if France conquered all of Spain, then Spanish-born people should still rule in the Americas. Castelli argued against this. He used the idea that if there was no rightful authority, power should return to the people. They should govern themselves.

The idea of removing the viceroy won. But Buenos Aires couldn't decide the new government alone. So, they would elect a temporary government. A meeting of representatives from all other cities would make the final decision. However, there were arguments about who should lead the temporary government. Some said the Cabildo should, others said a Junta. Castelli agreed with Saavedra's idea to form a Junta. But he added that the Cabildo's lawyer, Julián de Leiva, should have a deciding vote in choosing members. Castelli hoped this would include former supporters of Martín de Álzaga, like Mariano Moreno and Leiva himself.

However, Leiva used this power in a way Castelli didn't expect. Leiva formed a Junta with Cisneros as its president, meaning Cisneros would stay in power. The other members would have been two Spanish-born people and two criollos, Saavedra and Castelli. Most local people rejected this. They didn't want Cisneros to remain in power, even with a different title. They were suspicious of Saavedra's intentions and believed Castelli alone in the Junta couldn't achieve much. Castelli and Saavedra resigned that same day to pressure Cisneros to resign. The Junta with Cisneros never took power.

That same night, the criollos met at Rodríguez Peña's house. They made a list of members for a governing Junta, which was presented on May 25. Meanwhile, Domingo French, Antonio Beruti, and other armed men took control of the main square. The list included a mix of people from different political groups. Lezica finally told Cisneros that he was no longer in charge. The Primera Junta then took power.

Castelli and Mariano Moreno led the more radical ideas of the Junta. They became close friends and visited each other daily. Historians say they shared plans for a big political, social, and economic revolution, aiming for more freedom for Spanish American criollos. They were described as practical men, ready to reward allies and punish enemies of the revolution, even with executions. People called them "Jacobins," comparing them to the French Revolution's Reign of Terror. But they weren't necessarily French supporters. The similarities between the revolutions in France and Buenos Aires were mostly on the surface.

One of Castelli and the Junta's first actions was to send Cisneros and the judges of the Royal Audiencia back to Spain. They said it was for their own safety.

Stopping the Counter-Revolution

When former viceroy Santiago de Liniers heard about the new government, he started a counter-revolution from Córdoba. But Francisco Ortiz de Ocampo quickly defeated his forces and captured all the leaders. The first order was to send them to Buenos Aires. But after their capture, the Junta decided to execute them. All Junta members signed this decision, except Manuel Alberti, who, as a priest, could not agree to executions.

This decision was very unpopular in Córdoba. Liniers and the governor, Juan Gutierrez de la Concha, were well-liked. Executing a priest (Rodrigo de Orellana, another leader) was seen as wrong. Ocampo and Chiclana decided to follow the original orders and sent the prisoners to Buenos Aires.

The Junta repeated the order to execute them, but spared Bishop Rodrigo de Orellana, who was sent away instead. Castelli was given the job of making sure the execution order was carried out. Mariano Moreno told him, "Go, Castelli, and I hope you will not show the same weakness as our general. If it's not done, Larrea will go, and if needed, I'll go myself." Ocampo and Chiclana were removed from their positions. Castelli's helpers included Nicolás Rodríguez Peña, Diego Paroissien as a doctor, and Domingo French as head of the guards.

Castelli found the prisoners and ordered their execution. The governor of Córdoba, Juan Gutiérrez de la Concha, the former Viceroy, Santiago de Liniers, former Governor Santiago Alejo de Allende, Victorino Rodríguez, and the accountant Moreno were all executed. This happened at Cabeza de Tigre, on the border between Santa Fe and Córdoba. Bishop Orellana was not shot. He was forced to give spiritual comfort to the condemned and watch the executions. Domingo French was in charge of carrying out the executions.

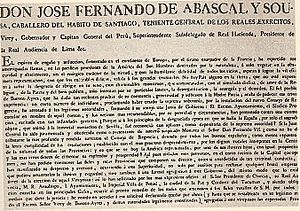

After executing Liniers, Castelli briefly returned to Buenos Aires and met Moreno. Moreno praised his actions and made him a representative of the Junta. Castelli was given full power to lead operations in La Paz. He also received instructions: Castelli was to put patriots in charge of the government, gain support from native people, and execute the president Nieto, governor Sanz, and the Bishop of La Paz if captured. He also had orders to capture and execute José Manuel de Goyeneche. Goyeneche had already defeated rebels in La Paz revolution (a rebellion similar to the May Revolution in modern Bolivia). Castelli was also told to rescue and recruit soldiers who had been sent to suppress earlier revolutions and were now prisoners in the Potosi mines. Many of these soldiers had died from working in the mines.

Campaign in Upper Peru

Castelli was not welcomed in Córdoba, where Liniers was popular. But he was well-received in San Miguel de Tucumán. In Salta, even though he was formally welcomed, he had trouble getting troops, supplies, money, and weapons. He took political command of the expedition to Upper Peru, replacing Hipólito Vieytes. He also replaced Ocampo with Colonel Antonio González Balcarce.

Castelli learned that Cochabamba had rebelled to support the Junta, but was threatened by royalist forces. Castelli intercepted a letter from Nieto to Gutiérrez de la Concha, the governor of Córdoba, who had already been executed. This letter mentioned a royalist army led by Goyeneche marching to Jujuy. Balcarce had advanced to Potosi but was defeated by Nieto at the Battle of Cotagaita. So, Castelli sent two hundred men and two cannons to help Balcarce. With these extra forces, Balcarce won the Battle of Suipacha. This victory allowed the patriots to control all of Upper Peru without opposition. One of the men sent was Martín Miguel de Güemes, who later led the Guerra Gaucha in Salta.

In Villa Imperial, a rich city in Upper Peru, an open cabildo asked Goyeneche to leave their territory. He obeyed because he didn't have enough military strength. The Bishop of La Paz, Remigio La Santa y Ortega, fled with him. Castelli was welcomed in Potosí and asked the locals to swear loyalty to the Junta. He also demanded that the royalist generals Francisco de Paula Sanz and José de Córdoba y Rojas surrender to him. He arranged for the capture of Vicente Nieto to be carried out only by the surviving soldiers from the mines of Potosi. These soldiers had been honored and joined the Army of the North. Sanz, Nieto, and Córdoba were executed in the Plaza of Potosí. Nieto claimed he died happy because he was under the Spanish flag. Goyeneche and Ortega, however, were safe in royalist territory. Bernardo Monteagudo, who had been in jail for his part in the 1809 revolution, escaped to join the army. Castelli, who knew Monteagudo's past, made him his secretary.

Castelli set up his government in Chuquisaca. There, he oversaw big changes for the entire region. He planned to reorganize the Mines of Potosi and reform the University of Charcas. He declared an end to native slavery and forced labor in Upper Peru. Native people were given the same political rights as criollos. Castelli also stopped new religious buildings from being built. This was to prevent religious groups from forcing native people into servitude while pretending to spread Christianity. He allowed free trade and gave land that had been taken from former workers back to them.

The decree was published in Spanish, Guarani, Quechua, and Aymara. He also started several bilingual schools. Many Indian chiefs took part in the first anniversary of the May Revolution. This was celebrated in Tiahuanaco, where Castelli honored the ancient Incas and encouraged people to fight against the Spanish. Even though they were welcomed, Castelli knew that most of the wealthy people supported the army out of fear, not true loyalty.

In November 1810, he asked the Junta for permission to cross the Desaguadero river, which was the border between the two viceroyalties. He wanted to take control of the Peruvian cities of Puno, Cuzco, and Arequipa. Castelli argued that it was important to rise against Lima. Its economy depended a lot on those areas. If they lost control there, the main royalist stronghold would be in danger. The plan was rejected as too risky, and Castelli followed his original orders.

In December, fifty-three Spanish-born people were sent away to Salta. The decision was sent to the Junta for approval. However, a Junta member, Domingo Matheu, who had business ties with some of them, arranged for the decision to be canceled. He argued that Castelli had been influenced by false accusations. Support for Castelli began to decrease. This was mainly because he treated native people favorably and because the church strongly opposed him. The church attacked the public atheism of Bernardo Monteagudo, Castelli's secretary. Both royalists in Lima and Saavedra in Buenos Aires compared them to Maximilien Robespierre, a leader during the Reign of Terror of the French Revolution.

Castelli also ended the mita in Upper Peru. This was a forced public service that was almost like slavery. Mariano Moreno also wanted to end the mita, but he had already resigned from the Junta. Without Castelli in Buenos Aires to help solve arguments, the disputes between Moreno and Saavedra had gotten worse. The Junta asked Castelli to be less extreme in his actions. But he continued with the ideas he shared with Moreno.

Several officers loyal to Saavedra planned to kidnap Castelli. They wanted to take him to Buenos Aires for trial and give command of the Army of the North to Juan Jose Viamonte. However, Viamonte did not agree to the plan when he was told about it by the conspirators. When Castelli learned about Moreno's resignation, he wrote a letter to Vieytes, Rodriguez Peña, Larrea, and Azcuénaga. He asked them to move to Upper Peru. If they defeated Goyeneche, they planned to march back to Buenos Aires. But the letter was sent by regular mail. The postmaster in Córdoba, Jose de Paz, sent it to Cornelio Saavedra instead. By then, the members of the Junta who supported Moreno had already been removed and sent away.

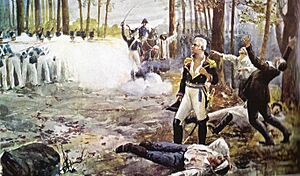

The Battle of Huaqui

The Junta's order not to advance into the Viceroyalty of Peru was like a temporary peace. It would last as long as Castelli didn't attack Goyeneche's army. Castelli tried to make this a formal agreement, which would mean the Spanish recognized the Junta as a real government. Goyeneche agreed to a truce for 40 days. This was supposedly to allow Lima to approve the agreement. But he actually used the time to make his army stronger. On June 19, while the truce was still in effect, a royalist troop attacked positions at Juraicoragua. Castelli declared the truce broken and declared war on Peru.

The royalist army crossed the Desaguadero on June 20, 1811. This started the Battle of Huaqui. The army waited near Huaqui, between the plains of Azapanal and Lake Titicaca. The patriotic left side, led by Diaz Velez, faced most of the royalist forces. The center was attacked by soldiers led by Pio Tristan. Many patriotic soldiers recruited in Upper Peru surrendered or ran away. Many recruits from La Paz even switched sides during the battle. The Saavedrist Juan José Viamonte helped Castelli's defeat by refusing to join the fight.

Even though the Army of the North didn't have huge losses, it was left without morale and fell apart. Goyeneche chased the fleeing patriots and captured Huaqui after his victory. The people of Upper Peru welcomed the royalists back. So, the army had to quickly leave those provinces. However, the resistance from Cochabamba stopped the royalists from advancing to Buenos Aires. Castelli moved to Quirbe and received orders to return to Buenos Aires for a trial. But by the time he was told, new orders had been issued. Castelli was to be kept in Catamarca, while Saavedra himself took charge of the Army of the North. Saavedra was removed from his position as soon as he left Buenos Aires and was confined to San Juan. The First Triumvirate, which was now governing, ordered Castelli to return.

Once in Buenos Aires, Castelli found himself alone politically. The Triumvirate and the newspaper La Gazeta blamed him for the defeat at Huaqui. They wanted to punish him as a warning to others. His former supporters were divided. Some supported the Triumvirate, and others could no longer help him. Castelli suffered from tongue cancer during the long trial. This made it harder and harder for him to speak. He died on October 12, 1812, while his trial was still happening.

Legacy

Juan José Castelli is not always given enough attention in Argentine history. Most historians focus on the arguments between Mariano Moreno and Cornelio Saavedra in the Junta. Castelli is often mentioned briefly as a supporter of Moreno. Even though he played a big part in the May Revolution, he wasn't the clear leader like José Gervasio Artigas was for the Cry of Asencio or Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla for the Cry of Dolores. The May Revolution happened because different groups wanted to remove the viceroy. Different historians highlight different groups.

Castelli is also largely overlooked in Bolivia. His support for the rights of native people, which is still an important issue there, and his religious views greatly affect how he is seen.

The most famous book about Castelli is Castelli, el adalid de Mayo (Castelli, the Champion of May). It was written by the Paraguayan Julio César Chaves. Andrés Rivera made Castelli more known to the public with his historical novel La revolución es un sueño eterno (The Revolution is an Eternal Dream). The popular historian Felipe Pigna wrote a whole chapter about Castelli in his book Los mitos de la historia argentina. This was later turned into a TV documentary called Algo habrán hecho por la historia argentina.

Images for kids

Error: no page names specified (help). In Spanish: Juan José Castelli para niños

In Spanish: Juan José Castelli para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |