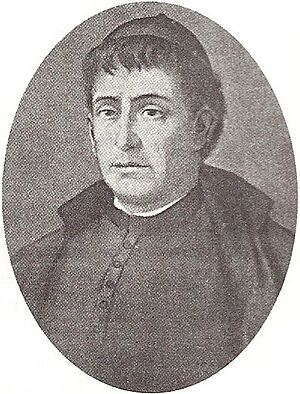

Manuel Alberti facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Manuel Alberti

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

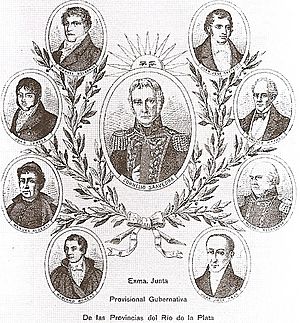

| Committee member of the Primera Junta | |

| In office 25 May 1810 – 11 January 1811 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 May 1763 Buenos Aires, Viceroyalty of Peru, Spanish Empire |

| Died | 31 January 1811 (aged 47) Buenos Aires, United Provinces of the Río de la Plata |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Alma mater | National University of Córdoba |

| Occupation | Priest |

| Signature |  |

Manuel Maximiliano Alberti (born May 28, 1763 – died January 31, 1811) was an Argentine priest. He was born in Buenos Aires when it was part of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, a Spanish colony.

Alberti served as a priest in Maldonado, Uruguay during the British invasions of the River Plate. He returned to Buenos Aires just in time for the May Revolution of 1810. He was chosen as one of the seven members of the Primera Junta. This group is seen as Argentina's first national government. Alberti supported many ideas from Mariano Moreno and worked for the Gazeta de Buenos Ayres newspaper. Sadly, arguments among the Junta members affected his health. He died from a heart attack in 1811.

Contents

Manuel Alberti's Life Story

Early Years and Education

Manuel Alberti Marín was born in Buenos Aires on May 28, 1763. His parents were Antonio Alberti and Juana Agustina Marín. He was baptized a few days later. Manuel had three brothers and three sisters. His family later helped a local charity by donating land.

He started his studies at the Real Colegio de San Carlos in 1777. He learned philosophy, logic, physics, and metaphysics. He finished his secondary education in 1779. The next year, he moved to Córdoba to study theology at the National University of Córdoba. Even with some health issues, he completed his studies. He earned his doctorate in theology and physics in 1785.

In 1786, he became a priest. He was assigned to the Concepción parish, where he had been baptized. He also worked for the House of Spiritual Works in Buenos Aires. He took on a new role in Magdalena in 1790. However, he resigned a year later due to health problems. After trying again in 1793, he resigned for good in 1794 and moved to Maldonado.

During the British Invasions

Maldonado was briefly taken over by British forces during the British invasions of the River Plate. This happened during the Napoleonic Wars. Alberti helped wounded Spanish soldiers and held funerals for those who died. He also secretly sent letters to Spanish authorities. These letters shared details about the British army in the city.

When the British found his letters, they arrested him. But a British officer, John Jaime Backhouse, later released him. This officer allowed Catholic religious practices to continue in the city. Eventually, Spanish forces led by Santiago de Liniers defeated the British. The British had to surrender and leave the area.

Joining the Primera Junta

Alberti returned to Buenos Aires in 1808. He became involved in politics, joining groups led by Miguel de Azcuénaga and Nicolás Rodríguez Peña. These groups wanted big political and social changes. Their efforts led to the May Revolution.

Alberti was chosen to attend an important meeting called an open cabildo on May 22, 1810. This meeting was to decide the future of the Spanish ruler, Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros. Alberti was among the many who voted to remove the ruler. He supported the idea of calling for representatives from other cities.

On May 25, Alberti learned he was chosen as a member of the new Primera Junta. This group replaced the Spanish ruler. The reasons for his selection are not fully clear. One idea is that he was chosen to balance different political groups. He might also have been picked to serve as the government's chaplain.

In the Junta, Alberti mostly agreed with the ideas of Mariano Moreno. He also sided with Juan Larrea and Juan José Castelli. He signed many rules that shaped the new political system. These rules supported ideas like popular sovereignty (people having power), representative government, and freedom of speech. They also supported the separation of powers (dividing government into different branches) and the idea of federalism (sharing power between a central government and local states).

However, Alberti did not support actions that went against his religious beliefs. For example, he refused to sign the order for the death penalty for Santiago de Liniers. Liniers had led a counter-revolution that was defeated. Alberti also worked for the Gazeta de Buenos Ayres newspaper, which the Junta created. He was in charge of choosing which news reports to publish. Some historians believe Alberti might have written the newspaper's main articles.

Later Conflicts and Death

Alberti's first disagreement with Moreno happened when Gregorio Funes arrived. Funes was a church leader from Córdoba who had ideas similar to Cornelio Saavedra, the Junta's president. Moreno wanted Alberti to write against Funes, but Alberti did not.

Alberti and Moreno grew further apart when the Junta voted to include representatives from other cities. At first, both opposed this idea. But Alberti eventually voted to accept it, saying it was for political reasons. This change turned the Primera Junta into the Junta Grande. Moreno, now in a minority group, resigned.

The addition of new representatives led to more arguments within the Junta. These conflicts affected Alberti's health. He had a mild heart attack on January 28, 1811. Three days later, he had another big disagreement with Funes. He suffered another heart attack on his way home and died. He was buried in the cemetery of San Nicolás de Bari. Alberti was the first member of the Primera Junta to pass away.

Remembering Manuel Alberti

All members of the Junta Grande attended Alberti's funeral, even his political rival Gregorio Funes. Domingo Matheu was very sad about his death. Alberti was replaced in the Junta by Nicolás Rodríguez Peña.

In his will, Alberti asked for a simple funeral. He left his belongings, like his house, farm, and books, to his siblings. Some of his personal diaries are still kept, but parts are missing. Historians have used his book collection to understand his ideas.

In 1822, the government of Buenos Aires named a street after him. In 1910, a statue of him was put up in Barrancas de Belgrano. A district in Buenos Aires Province, Manuel Alberti, is also named in his honor.

See also

In Spanish: Manuel Alberti para niños

In Spanish: Manuel Alberti para niños

- Gregorio Funes

- Francisco de Paula Castañeda

Images for kids