Manuel Belgrano facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Manuel Belgrano

|

|

|---|---|

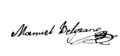

Portrait of Manuel Belgrano by François-Casimir Carbonnier made during Belgrano's diplomatic mission to London (1815)

|

|

| Committee member of the Primera Junta | |

| In office 25 May 1810 – 26 September 1810 Serving with Manuel Alberti, Miguel de Azcuénaga, Juan José Castelli, Domingo Matheu and Juan Larrea

|

|

| Perpetual secretary of the Commerce Consulate of Buenos Aires | |

| In office 2 June 1794 – April 1810 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Manuel José Joaquín del Corazón de Jesús Belgrano

3 June 1770 Buenos Aires, Governorate of the Rio de la Plata, Viceroyalty of Peru (Now Argentina) |

| Died | 20 June 1820 (aged 50) Buenos Aires, United Provinces of the Río de la Plata |

| Political party | Carlotism, Patriot |

| Alma mater | University of Valladolid |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1810–1819 |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | |

Manuel Belgrano (born June 3, 1770 – died June 20, 1820) was a very important person in Argentina's history. He was a lawyer, politician, journalist, and military leader. He played a key role in the Argentine Wars of Independence, which helped Argentina become free from Spain. He is most famous for creating the Flag of Argentina. Many people consider him one of the main "Founder Fathers" of the country.

Belgrano was born in Buenos Aires, which was then part of the Spanish colony called the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. He studied in Spain and learned about new ideas from the Age of Enlightenment, which focused on freedom and human rights. When he returned home, he wanted to bring these new ideas to his country. He worked to make his homeland more independent from Spanish rule.

He supported the May Revolution in 1810, which removed the Spanish leader (the viceroy) from power. Belgrano was chosen as a member of the new government, called the Primera Junta. He later became a military leader, even though he wasn't trained as a soldier at first. He led troops in several important battles and campaigns, including the Paraguay campaign and leading the Army of the North. His victories, like the Battle of Tucumán and the Battle of Salta, were crucial for Argentina's independence.

Belgrano also went on a diplomatic mission to Europe to get support for the new government. He returned in time for the Congress of Tucumán in 1816, where Argentina officially declared its independence. He passed away in 1820, leaving behind a lasting legacy as a hero of Argentina.

Contents

Manuel Belgrano's Life Story

Early Life and Studies

Manuel Belgrano was born in Buenos Aires on June 3, 1770. His family lived in a wealthy part of the city. He was considered a criollo, meaning he was born in the Americas to Spanish parents. This social class had fewer rights than people born in Spain.

His father, Domingo, was an Italian merchant. He was allowed by the King of Spain to move to the Americas. Domingo was a successful businessman and helped set up the Commerce Consulate of Buenos Aires, which Manuel would later lead. Manuel's mother, María Josefa, was from Santiago del Estero, Argentina.

Manuel went to the San Carlos school, where he studied many subjects like Latin, philosophy, and physics. He graduated in 1786. His father sent him and his brother Francisco to study in Europe. Manuel chose to study law, even though his father wanted him to study commerce. He was a very good student and was even allowed to read books that were usually forbidden in Spain. This is how he learned about new ideas from important thinkers like Montesquieu and Rousseau.

While in Spain, Belgrano was surrounded by discussions about the French Revolution. People talked a lot about ideas like equality and freedom. Even with these new ideas, Belgrano remained a strong Catholic and believed in a monarchy (a government led by a king or queen). However, he thought the monarchy should be more modern and fair.

He also studied languages, economics, and public rights. He was very interested in ideas about helping the public and making people prosperous. He translated a book about how a country's economy should be run, focusing on agriculture. He believed that countries should use their natural resources wisely and that the government should help people get a good education.

Working at the Consulate

When Belgrano returned to Buenos Aires in 1794, he became the "perpetual secretary" of the Commerce Consulate of Buenos Aires. This new office handled business and trade issues for the Spanish crown. He stayed in this job until 1810. His main goal was to improve farming, industry, and trade in the region.

Belgrano believed that education was key to making the country richer. He tried to create schools for navigation, commerce, and drawing. He wanted to teach young people useful skills and encourage them to work for the good of their nation. However, these schools were later closed by the Spanish authorities, who thought they were too expensive for a colony.

He also tried to promote new crops like linen and hemp. He wanted to help local businesses and make sure the country had enough food. He suggested giving awards to people who found ways to boost the local economy. But many of his ideas were rejected by other merchants who wanted to keep the old ways of trade.

Belgrano also helped start the city's first newspaper, the Telégrafo Mercantil. He used newspapers to share his economic ideas. He believed that the country should make its own goods and sell them, instead of just importing everything. He also thought it was important to avoid buying luxury goods from other countries.

British Invasions

Belgrano was appointed as a captain in the local militias in 1797. This was to prepare for possible attacks from the British or Portuguese. His first real experience in battle was during the British invasions of the River Plate in 1806. The British captured Buenos Aires. Belgrano tried to fight, but his untrained men scattered after the first British cannon shot. He later wrote that he wished he had known more about military tactics then.

After the British took the city, they asked all Spanish officials to promise loyalty to the British crown. Belgrano refused. He said he wanted "either our old master, or no master at all." He escaped Buenos Aires to avoid being forced to pledge loyalty.

The British were eventually defeated by a force led by Santiago de Liniers. Belgrano returned and joined the army, studying military strategy. When the British attacked again in 1807, he served as an assistant in a division. After the invasions, Belgrano went back to his work at the consulate. He even met a British officer who offered support for independence, but Belgrano turned him down, fearing Britain might abandon them later.

Carlotism and the May Revolution

Belgrano was a main supporter of a political idea called Carlotism. This idea came about because the Spanish king, Ferdinand VII, was captured by the French during a war in Europe. Carlotism suggested that Carlota Joaquina, the king's sister who lived in Brazil, should become the ruler of the Spanish colonies in America. Belgrano and other leaders thought this could help the colonies gain more independence.

However, this plan faced strong opposition. Many people worried that it was a trick for Portugal (Carlota's husband was a Portuguese prince) to take over. Also, Carlota wanted to be an absolute ruler, while Belgrano and his friends wanted a more modern, fair government. By 1810, the Carlotist idea was dropped.

When news arrived that Spain was losing the war in Europe, many people in Buenos Aires felt that the Spanish viceroy no longer had authority. Belgrano and other leaders decided it was time to act. They pushed for an "open cabildo," which was a special meeting where important citizens could discuss the government.

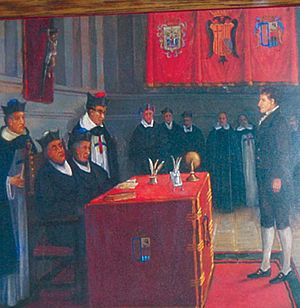

On May 22, 1810, the meeting was held. Belgrano supported the idea that the Spanish colonies were loyal only to the King of Spain, not to Spain itself. Since the king was captured, the people had the right to govern themselves. The meeting voted to remove the viceroy. After some disagreements, a new government called the Primera Junta was formed on May 25, 1810. Belgrano was chosen as one of its members. He later wrote that he was surprised by his appointment but accepted the important role.

Military Campaigns and the Flag

Expedition to Paraguay

Three months after the Primera Junta was formed, Manuel Belgrano was made the Chief Commander of an army. His mission was to gain support for the new government in other parts of the region, especially Paraguay. The Junta believed that many people in Paraguay supported their cause.

Belgrano set off with about 200 men, hoping to gather more along the way. His army grew to about 950 soldiers. They were welcomed by most people they met, receiving donations and new recruits. Belgrano also took steps to help the native people living in missions, giving them full civil rights and allowing them to trade freely.

However, the campaign in Paraguay was very difficult. The Paraná River was a huge natural barrier, and the land beyond it was hard to cross. Belgrano's army was greatly outnumbered by the Paraguayan forces led by Governor Velazco. In the Battle of Paraguarí, Belgrano's troops were defeated. Even after this loss, Belgrano wanted to keep fighting, but his officers convinced him to retreat.

They moved to Tacuarí, where they were attacked again in the Battle of Tacuarí. Belgrano's small army of 400 men faced nearly 3,000 Paraguayan soldiers. Despite being heavily outnumbered, Belgrano refused to surrender. He ordered his remaining men to fire their cannons, which made the Paraguayan soldiers scatter. Belgrano then asked for a truce and promised to leave the province.

Even though it was a military defeat, Belgrano's campaign in Paraguay had an important result. It led the Paraguayans to declare their own independence from Spain.

Creating the Flag of Argentina

After the defeat in Paraguay, Belgrano was ordered to fortify the city of Rosario against possible attacks from royalist forces (those loyal to Spain). He built two strongholds there. He noticed that both the patriots and the royalists were fighting under the same Spanish colors. To create a symbol for the new nation, he designed a cockade of Argentina (a ribbon worn on a hat) in light blue and white. The government approved its use.

Belgrano then created a flag using the same light blue and white colors. He raised this flag for the first time in Rosario near the Paraná River on February 27, 1812. On that very day, he was also appointed to lead the Army of the North.

The government in Buenos Aires did not initially approve of his new flag. Belgrano didn't know this right away. He had the flag blessed by a priest in Salta on the second anniversary of the May Revolution. When he finally learned that the flag wasn't approved, he put it away. He said he was saving it for a great victory.

Later, a large royalist army advanced from the north, ready to invade. Belgrano's army was much smaller. He ordered a massive Jujuy Exodus: the entire population of the city of Jujuy had to leave with the army, taking everything valuable so the royalists couldn't use it. This was a very difficult journey.

Despite being outnumbered, Belgrano decided to make a stand at San Miguel de Tucumán. His forces had grown to about 1,800 soldiers, but the royalists still had 3,000. Even so, Belgrano won a key victory in the Battle of Tucumán.

After this, a new government in Buenos Aires, the Second Triumvirate, gave Belgrano more support. They called an assembly that allowed Belgrano to use the blue and white flag as the flag for the Army of the North.

Belgrano then won another major victory at the Battle of Salta. This was the first battle fought with the newly approved flag. He defeated the royalist army and captured all their soldiers. These victories were very important because they secured Argentina's control over the northwest and stopped the royalists from advancing further into the country.

Campaign to Upper Peru

In June 1813, Belgrano set up a base in Potosí with 2,500 men to prepare for an attack on Upper Peru. He tried to improve relations with the native people in the area. However, his plans were discovered by the royalists.

Belgrano was surprised at the Battle of Vilcapugio and, despite an initial advantage, his army was defeated. He gathered his remaining soldiers and was ready for another fight. But on November 14, he was defeated again at the Battle of Ayohuma. He had to retreat his army back to Jujuy.

Because of these defeats and Belgrano's poor health, the government sent José de San Martín to take command of the Army of the North. Belgrano became his second-in-command. They met at the Yatasto relay in Salta. Belgrano gave San Martín full control to make changes.

Belgrano was later ordered to return to Buenos Aires to be judged for the defeats. However, San Martín refused to send him because of his bad health. Eventually, Belgrano did go to Córdoba and wrote his autobiography while waiting for the trial. All charges against him were later dropped. The government then sent him on a diplomatic mission to Europe, trusting his skills to gain support for Argentina's independence.

Declaration of Independence

By 1814, the Spanish King Ferdinand VII was back on his throne and trying to regain control of his colonies. Belgrano and another leader, Bernardino Rivadavia, went to Europe to seek support for the United Provinces (Argentina). Their diplomatic mission didn't fully succeed, but Belgrano learned that European powers preferred constitutional monarchies (where a king or queen rules with a constitution) over republics. He also realized that European countries approved of South American revolutions, but not if they led to chaos.

When Belgrano returned, he met with the Congress of Tucumán in July 1816. He explained what he had learned in Europe. He suggested that creating a local monarchy might help prevent chaos and make Argentina's independence more accepted by European powers. He proposed the Inca plan: a monarchy ruled by a descendant of the Inca civilization. He thought this would also gain support from the native populations.

This idea was supported by San Martín and others, but the delegates from Buenos Aires strongly rejected it. They didn't want Cuzco (the old Inca capital) to be the capital of the new country. On July 9, 1816, the Congress finally signed the Declaration of Independence from Spain. The flag created by Belgrano was officially accepted as the national flag.

After this, Belgrano again took command of the Army of the North. His main job was to protect Tucumán from royalist attacks while San Martín prepared his Army of the Andes for a different plan: crossing the Andes mountains to fight the royalists in Chile.

Manuel Belgrano's Last Years

In 1819, Buenos Aires was fighting against other regional leaders. Belgrano was asked to bring his army back to help. He agreed, even though his health was very poor. He refused to resign, believing his presence was important for the army's morale.

His health continued to get worse. He was given unlimited leave from work and traveled to Tucumán. During his stay, the governor of Tucumán was removed from power, and Belgrano was briefly held prisoner. However, he was soon released when a new government took control.

He returned to his parents' house in Buenos Aires. The city was in a state of chaos at that time. On June 20, 1820, Manuel Belgrano passed away at the age of 50 due to a condition called dropsy (edema). He had become very poor because the war had used up all his wealth. He reportedly paid his doctor with his clock and carriage, which were some of his last possessions. He was buried in the Santo Domingo convent. His last words were reportedly: "¡Ay, Patria mía!" (Oh, my country!).

Because of the chaos in the city, Belgrano's death went largely unnoticed at the time. Only one newspaper mentioned it, and there was no government presence at his funeral. The following year, when things were calmer, a large state funeral was organized for him. In 1902, his body was moved to a mausoleum.

Manuel Belgrano's Ideas

Political and Economic Views

Manuel Belgrano was a very intelligent person who knew a lot about the important topics of his time. He studied in Europe during a period of big changes and could speak many languages. This allowed him to read influential books from the Age of Enlightenment. He helped spread these new ideas through newspapers and his work at the consulate.

He believed in the "common good," which meant that public health, education, and work were important for everyone. He was a strong Catholic and believed in a monarchy, but he wanted it to be a constitutional monarchy, like in Britain, where the ruler's power is limited by laws.

In economics, he believed that a country's wealth came from nature, especially agriculture. He wanted to improve farming, livestock, and manufacturing. He also supported free trade. He worked to create maps of the country, which later helped José de San Martín during his famous Crossing of the Andes. He introduced new crops and encouraged the use of local animals for food production.

Promoting Education

Manuel Belgrano was one of the first politicians to strongly support the development of a good education system. In his first report as head of the Commerce Consulate, he suggested creating schools for agriculture and commerce. These schools would teach important things like how to grow crops, preserve seeds, and deal with pests.

He cared about all levels of education, not just higher education. He promoted the creation of free schools for poor children. In these schools, children would learn to read, basic math, and religious teachings. He believed this would help people become hardworking and reduce laziness.

He also supported creating schools for girls, where they would learn weaving and reading. He wanted to prevent ignorance and laziness and teach them skills useful for daily life.

Belgrano showed his commitment to public education in a big way. In 1813, he was rewarded with 40,000 pesos for his victories at Salta and Tucumán. This was a lot of money! But Belgrano refused to keep it for himself. He gave it back to the government, asking them to use it to build primary schools in several cities. He even gave instructions on how to choose the best teachers. Sadly, these schools were not built, and the money was eventually lost.

Manuel Belgrano's Legacy

Manuel Belgrano is considered one of Argentina's greatest heroes. A large monument called the National Flag Memorial was built in 1957 in Rosario to honor the flag he created. Every Flag Day, on June 20 (the anniversary of Belgrano's death), national celebrations are held there. Since 2002, Jujuy Province is declared the honorary capital of Argentina every August 23, remembering the Jujuy Exodus.

Many things in Argentina are named after him. The cruiser ARA General Belgrano, which was sunk during the Falklands War, was named in his honor. There's also Puerto Belgrano, the largest base of the Argentinian navy. A small town in Córdoba, Villa General Belgrano, and many other towns and departments bear his name. Avenida Belgrano in Buenos Aires and part of the avenue leading to the Flag Memorial in Rosario are also named after him. There's even a neighborhood in Buenos Aires called Belgrano.

In a museum in Sucre, Bolivia, there is an old, deteriorated Argentine flag. They claim it is the original flag first raised by Belgrano in 1812. This flag was hidden in a small church after a battle in 1813. Another flag was returned to Argentina by Bolivia in 1896.

In Genoa, Italy, there is a statue of Belgrano.

Historiography

Manuel Belgrano wrote his own autobiography, which was later discovered and published by the historian Bartolomé Mitre. Mitre wrote a very important book called Historia de Belgrano y de la Independencia Argentina (History of Belgrano and of the Independence of Argentina). This book not only told Belgrano's life story but also detailed the entire Argentine War of Independence.

Mitre's book was very influential, but it also sparked debates among other Argentine historians. Some historians, like Dalmacio Vélez Sarsfield, argued that Mitre focused too much on Belgrano and Buenos Aires, and didn't give enough credit to the efforts of other provinces in the fight for independence. These discussions about Belgrano's life and the history of Argentina are considered the starting point for how Argentine history is studied today.

Money and Stamps

Belgrano's image has appeared on many Argentine banknotes and coins throughout history. He was first featured on banknotes in the 1970s. Today, he is displayed on the 10-peso banknote.

See also

In Spanish: Manuel Belgrano para niños

In Spanish: Manuel Belgrano para niños

Images for kids