Inca plan facts for kids

The Inca plan was an idea suggested in 1816 by Manuel Belgrano to the Congress of Tucumán. Its goal was to crown an Inca as the ruler of the new country. After the Declaration of Independence of the United Provinces of South America (which is now Argentina), the Congress had to decide how the country should be governed. Belgrano thought the best way was to have a Constitutional monarchy, led by someone from the Inca royal family. This idea was liked by José de San Martín, Martín Miguel de Güemes, and the northern provinces. However, people from Buenos Aires strongly disagreed. In the end, the Congress decided against the Inca plan and created a Republic instead.

Contents

Why the Inca Plan Was Suggested

The king of Spain, Ferdinand VII of Spain, was removed from his throne by French armies during a war. This left the Spanish colonies, like the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, without a clear ruler. At the same time, new ideas about freedom and government were spreading from the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution.

When Ferdinand VII returned to power in 1816, he wanted to bring back the old way of ruling, where the king had all the power. This made the people fighting for independence realize they needed to be fully independent from Spain.

At the same time, there was a fight within the new country. Buenos Aires, which had been the capital of the Spanish colony, wanted to keep its power. But the other provinces felt they could rule themselves, especially without a king. This led to a Argentine Civil War between Buenos Aires and leaders from the provinces called caudillos.

The Inca Empire had been conquered by the Spanish many years ago. The last Inca ruler, Atahualpa, was executed in 1533. Even so, the Inca heritage was still very important to the native people in the northern parts of the country, and some Inca noble families still existed.

How the Plan Developed

After King Ferdinand VII returned to Spain, Manuel Belgrano and Bernardino Rivadavia went to Europe to get support for the new governments in South America. They didn't get much help. But Belgrano noticed that European countries now preferred monarchies over republics. He also saw that European powers worried about the new countries becoming too chaotic.

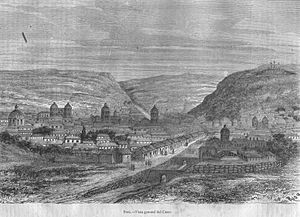

This made him think that if the United Provinces had an Inca monarch, European countries might be more likely to accept their independence. Also, bringing back the Inca monarchy would gain support from the northern provinces and the native people. The plan also suggested making Cuzco, the old capital of the Inca Empire, the new capital of the country, instead of Buenos Aires.

This idea wasn't completely new. As early as 1790, Francisco de Miranda had a similar plan for an empire where an Inca descendant would rule. His idea was a constitutional monarchy with a parliament, including a group of local leaders called caciques.

Two possible candidates for the Inca throne were Dionisio Inca Yupanqui, a colonel in Spain, and Juan Bautista Tupamaro, also known as Túpac Amaru. Juan Bautista claimed to be related to the former Inca ruler Túpac Amaru.

Belgrano's idea was discussed again on July 12 by Manuel Antonio de Acevedo. The representatives from the northern provinces strongly supported it. Those from the Cuyo region were split, and the representatives from Buenos Aires were against it. People from Buenos Aires didn't like the idea of losing power and being ruled by a government in Cuzco. They suggested a young European prince, Don Sebastián, as king instead.

The discussion continued through July. On August 6, Tomás de Anchorena spoke against the Inca plan. He felt that people in the North and the Pampas had different views, with the Pampas opposing a monarchy. However, years later, Anchorena explained that he supported a constitutional monarchy but not an Inca king.

Belgrano wrote that the project had full agreement. Martín Miguel de Güemes and José de San Martín also supported it. San Martín wanted a single leader for the country, not a group of people like the Juntas or triumvirates that had ruled before.

The representatives from Buenos Aires couldn't stop the Inca plan directly. So, they delayed it and pushed for the Congress to move to Buenos Aires. This would give them more influence. Belgrano and Güemes wanted to keep the Congress in Tucumán. San Martín agreed to the move but wanted the main government office to be in Córdoba. Buenos Aires won, and the Congress moved there in March 1817.

The Inca Plan was then forgotten. Instead, the Congress created a constitution that would lead to a monarchy, but the king would not be an Inca. They suggested a French prince, Charles II, Duke of Parma. However, this plan failed when Buenos Aires lost a battle, which ended the power of the main leaders and started a period of anarchy (a time without a strong central government).

The Duke of Lucca was also considered for marriage to a Brazilian princess. Her family would give land to the United Provinces as part of her marriage gift. This land was a disputed area that the United Provinces was fighting over with Brazil. But this plan also failed because the king of Spain did not want any of his relatives to become monarchs in his former colonies.

Different Views on the Plan

Historians have different opinions about Belgrano and San Martín wanting a monarchy. Bartolomé Mitre, a writer, thought they didn't understand what the people wanted at the time. He believed that even though they supported a monarchy, their actions helped the country become a democratic republic. Mitre saw the Inca plan as a weak idea that San Martín only supported to make the government stronger.

Juan Bautista Alberdi, another historian, said it was wrong to judge their support for monarchy without looking at the specific situation. Historian Milcíades Peña also pointed out that monarchies were helpful in earlier times in Europe to turn small areas into strong countries. From this view, Belgrano and San Martín might have supported monarchy because South America was still developing, similar to earlier Europe.

According to Alberdi, the real issue wasn't just about monarchy versus republic. It was about the power struggle between Buenos Aires and the other provinces. Those who supported the Inca plan wanted a strong central government that would unite all of Hispanic South America. Buenos Aires, however, wanted to keep its own power over the region. Alberdi described it as "two countries, two causes, two interests" under the name of one country, with Buenos Aires trying to control the provinces.

See also

In Spanish: Plan del Inca para niños

In Spanish: Plan del Inca para niños