Juan Bautista Alberdi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Juan Bautista Alberdi

|

|

|---|---|

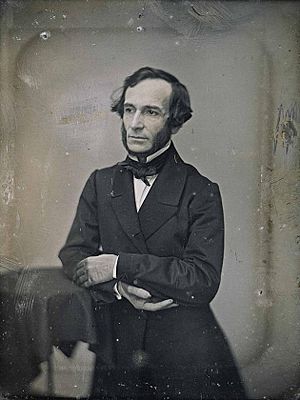

Daguerreotype taken in Chile, dated between 1850 and 1853

|

|

| Born | August 29, 1810 |

| Died | June 19, 1884 (aged 73) Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

|

| Other names | Figarillo |

|

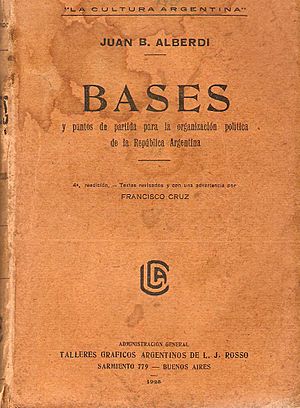

Notable work

|

Bases y puntos de partida para la organización política de la República Argentina |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Generation of '37's Classical liberalism - May Association |

|

Main interests

|

Politics Law |

|

Influences

|

|

| Signature | |

Juan Bautista Alberdi (born August 29, 1810 – died June 19, 1884) was an important Argentine thinker and diplomat. He spent much of his life living outside Argentina, in places like Montevideo, Uruguay and Chile. Even so, his ideas greatly shaped the Constitution of Argentina of 1853.

Alberdi believed in liberal and federal ideas for a country's laws. He wanted to find a way to balance different groups' needs. He aimed for a strong central government but also wanted provinces to have some local control. He thought both approaches would help Argentina grow and become a strong, united nation.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Juan Bautista Alberdi was born in San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina, on August 29, 1810. His father, Salvador Alberdi, was a Spanish merchant. His mother, Josefa Aráoz y Balderrama, was from an Argentine family. Sadly, she passed away shortly after Juan Bautista was born.

His father supported the fight for Argentina's independence. He even met with General Manuel Belgrano during the war. After his father died in 1822, Juan Bautista's older siblings, Felipe and Tránsita, became his guardians.

Alberdi received a scholarship to study in Buenos Aires at the School of Moral Sciences. This school is now known as the "Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires". He studied with other future leaders like Vicente Fidel López and Esteban Echeverría.

He found the school's rules very strict and even left for a short time. He became very interested in music and taught himself a lot about it. In 1832, he wrote his first book, El espíritu de la música (The spirit of music). He later went back to formal studies at the University of Córdoba. He also wrote a report about Tucumán for the governor, Alejandro Heredia.

A Time of Civil War

Back in Buenos Aires, Alberdi became good friends with Juan María Gutiérrez and Esteban Echeverría. They formed a group of young, liberal thinkers called the "Generation of '37". They met at a place called the Marcos Sastre literary hall.

This group criticized both sides of Argentina's Argentine Civil Wars. They felt the federalists were too violent and the unitarians couldn't govern well. They wanted both groups to stop fighting and work together for Argentina.

The governor, Juan Manuel de Rosas, closed their meeting hall. So, Alberdi started a women's magazine called "La Moda" (The fashion). He wrote under the pen name "Figarillo." Even though it was a fashion magazine, it also included political ideas. Alberdi was also concerned about Argentina's legal system. He wrote Fragmento preliminar al estudio del derecho (Preliminary fragment of the study of law). This book pointed out problems and suggested ways to fix them.

The "Generation of '37" continued as a secret group called the "May Association." But the government found out about them. Many members had to leave the country. Alberdi moved to Uruguay in 1838.

In Montevideo, he finally became a lawyer. He had finished his studies in Buenos Aires but refused to take the oath under Rosas's government. Alberdi believed that the real issue in Argentina wasn't just Rosas, but the society that supported him. He thought his generation needed to understand why people supported Rosas and how to gain their trust.

He wrote for newspapers that opposed Rosas, like "El Grito Arjentino" (The Argentine Cry) and "Muera Rosas" (Death to Rosas). He also wrote plays, including "La Revolución de Mayo" (The May Revolution) and "El gigante Amapolas" (The giant Poppies). The name "Amapolas" was a clever play on words related to Rosas's last name.

Alberdi also worked as a secretary for Juan Lavalle, a general who fought against Rosas. But Alberdi left him due to political disagreements. When Manuel Oribe, an ally of Rosas, surrounded Montevideo in 1840, Alberdi left for Europe with Juan María Gutiérrez.

While in Paris, Alberdi met José de San Martín, a hero of Argentina's independence. Alberdi admired San Martín's humility and energy. In 1843, Alberdi returned to the Americas and settled in Valparaíso, Chile. He renewed his law degree and worked as both a lawyer and a journalist, still using the name "Figarillo."

He studied the United States Constitution to find ideas that could help Argentina. In 1844, he wrote Sobre la conveniencia de un Congreso General Americano (About the convenience of a General American Congress). He also started a newspaper called El Comercio. In 1847, he wrote La República Argentina 37 años después de su Revolución de Mayo (The Argentine Republic 37 years after its May Revolution). In this report, he called for an end to the fighting between political groups. Finally, Rosas was defeated in 1852 by Justo José de Urquiza at the battle of Caseros.

A Diplomat for Argentina

After Rosas was removed from power, Urquiza called for a meeting to create a new constitution. Alberdi strongly supported this idea. He wrote Bases y puntos de partida para la organización política de la República Argentina (Bases and starting points for the political organization of the Argentine republic). This book was a draft for the new constitution and was heavily influenced by the United States Constitution.

Alberdi also wrote Elementos de derecho público provincial Argentino (Elements of Argentine provincial civic law). In this work, he compared Argentina's 1826 constitution with the U.S. Constitution. He believed that Argentina's biggest problem was its small population compared to its huge size. He often called the countryside a "desert." His main solution was to encourage many Europeans to move to Argentina. His most famous saying is "Gobernar es poblar" (To govern is to populate), meaning "To govern is to populate the country."

He also suggested improving roads, bridges, and ports. He wanted to bring new technologies like the telegraphy and railways to Argentina. Alberdi also supported economic liberalism, which meant less government control over the economy.

Urquiza, who became the first president under the new 1853 constitution, liked Alberdi's work. He made Alberdi the ambassador for the Argentine Confederation in Chile. At this time, Buenos Aires had separated from the Confederation.

The writer Domingo Faustino Sarmiento disagreed with Urquiza and also criticized Alberdi. Sarmiento thought Urquiza was just another powerful leader like Rosas. Alberdi, on the other hand, believed Buenos Aires was still acting like Rosas's government in its dealings with other provinces. Alberdi explained his ideas in his Cartas Quillotanas. Sarmiento replied with his own writings.

Urquiza offered Alberdi the job of finance minister, but Alberdi turned it down. Instead, Urquiza sent him to Europe. Alberdi's mission was to get European countries to recognize Argentina's independence (declared in 1816) and its new constitution. He also had to prevent them from recognizing Buenos Aires as a separate country.

On his way to Europe, Alberdi visited the United States and met President Franklin Pierce. He then went to London, where he met Queen Victoria. Finally, he settled in Paris, where he would live for 24 years.

In Paris, Alberdi met the French emperor Napoleon III. Alberdi convinced him to recognize the Argentine Confederation. He also persuaded the emperor to remove the French diplomat from Buenos Aires and send one to the Confederation instead.

In 1857, Alberdi began talks with Spain to recognize Argentina's independence. He proposed two agreements. The first stated that Spain would no longer claim control over Argentine land. The second opened Argentina to trade. He also suggested that Argentina would take on the old debts of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (the Spanish colony before Argentina). These agreements were signed in 1857 and 1859 and confirmed by the Spanish queen Isabella II in 1860. However, the governor of Buenos Aires, Carlos Tejedor, rejected Alberdi's agreements.

Alberdi also met Rosas, who was living in England after leaving power. In 1861, the Argentine Confederation and Buenos Aires reunited. This meant Alberdi's work as ambassador ended. He was against the War of the Triple Alliance and argued about it with President Bartolomé Mitre. During this time, he started writing El crimen de la guerra (The crime of war), a book that was published after his death.

Later Years and Legacy

Alberdi returned to Argentina in 1879, after living abroad for over forty years. He was chosen to represent Tucumán, but his appointment was blocked during a political uprising. The civil war ended in 1880, and Buenos Aires became the federal capital.

By this time, Alberdi had received many honors. A village in Santa Fe Province was named after him. President Julio Argentino Roca even asked Congress to publish all of Alberdi's writings. The newspaper La Nación, started by Mitre, criticized these honors.

Alberdi was sent to Europe again, but he had a stroke during the journey. His health quickly worsened, and he passed away near Paris on June 19, 1884.

Juan Bautista Alberdi was a very important member of the 1837 generation. This group helped imagine and begin building a successful Argentina with many freedoms. Alberdi's ideas for the country's future, based on rules, values, and ethics, were very influential. He is also known as a great legal expert.

Today, his political and economic ideas are still supported by many Argentine liberal and libertarian economists and thinkers.

See also

In Spanish: Juan Bautista Alberdi para niños

In Spanish: Juan Bautista Alberdi para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |