Juan Manuel de Rosas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Juan Manuel de Rosas

|

|

|---|---|

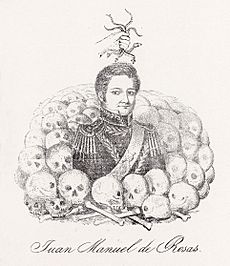

Posthumous portrait of Juan Manuel de Rosas wearing the full dress of a brigadier general

|

|

| 13th and 17th Governor of Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office 7 March 1835 – 3 February 1852 |

|

| Preceded by | Manuel Vicente Maza |

| Succeeded by | Vicente López y Planes |

| In office 6 December 1829 – 5 December 1832 |

|

| Preceded by | Juan José Viamonte |

| Succeeded by | Juan Ramón Balcarce |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas

30 March 1793 Buenos Aires, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, Spanish Empire |

| Died | 14 March 1877 (aged 83) Southampton, United Kingdom |

| Resting place | La Recoleta Cemetery, Buenos Aires |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse |

Encarnación Ezcurra

(m. 1813; died 1838) |

| Children |

|

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Battles/wars | British invasions of the River Plate Desert Campaign (1833–1834) Battle of Caseros |

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas (born March 30, 1793 – died March 14, 1877) was an important Argentine politician and army officer. People often called him the "Restorer of the Laws." He ruled Buenos Aires Province and briefly the Argentine Confederation.

Even though he was born into a rich family, Rosas became very wealthy on his own. He bought huge amounts of land. Like many landowners, he had his own private army made up of his workers. He joined in the many civil wars that happened in his country. Rosas won battles and became very powerful. With his large landholdings and loyal private army, he became a caudillo, which was a name for provincial warlords. He rose to the highest rank in the Argentine Army, brigadier general. He became the undisputed leader of the Federalist Party.

In December 1829, Rosas became governor of Buenos Aires province. He set up a dictatorship that used fear to control people. In 1831, he signed the Federal Pact, which gave provinces more freedom. This also created the Argentine Confederation. When his first term ended in 1832, Rosas went to the frontier to fight against the native peoples. After his supporters took control of Buenos Aires, Rosas was asked to return. He became governor again. Rosas brought back his strict rule and formed the Mazorca, a group that used violence against citizens. Elections became unfair, and the government branches simply did what he wanted. Rosas created a "cult of personality," making himself seem like an all-powerful leader. His rule became very controlling, affecting all parts of society.

Rosas faced many challenges in the late 1830s and early 1840s. He fought a war against the Peru–Bolivian Confederation. France also blocked the port of Buenos Aires. He dealt with a rebellion in his own province and a big uprising that spread to five northern Argentine provinces. Rosas overcame these challenges and gained more influence over the other provinces. By 1848, he controlled all of Argentina. Rosas also tried to take over the nearby nations of Uruguay and Paraguay. France and Great Britain tried to stop Argentina's expansion by blocking Buenos Aires for several years. But they could not stop Rosas, and his success made him even more respected.

When the Empire of Brazil started helping Uruguay fight Argentina, Rosas declared war in August 1851. This began the Platine War. Rosas was defeated in this short conflict and fled to Britain. He spent his last years living as a farmer in exile until he died in 1877. Many Argentines remember Rosas as a harsh ruler. Since the 1930s, a political movement called Revisionism has tried to improve Rosas's image. They wanted to create a new dictatorship like his. In 1989, his remains were brought back to Argentina to help unite the country. Rosas is still a debated figure in Argentina today.

Contents

Early Life and Beginnings

Childhood and Education

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas was born on March 30, 1793. His family lived in a town house in Buenos Aires. This city was the capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. He was the first child of León Ortiz de Rosas and Agustina López de Osornio. His father was a military officer. His mother came from a rich Criollo family. Juan Manuel's mother, Agustina, was a very strong and determined woman. She got these traits from her father, Clemente López de Osornio. He was a landowner who died defending his property.

Like many children at that time, Rosas was taught at home until he was 8 years old. Then, he went to the best private school in Buenos Aires. His education was typical for a wealthy landowner's son. He later learned more by reading on his own.

In 1806, a British army invaded Buenos Aires. Rosas was 13 years old. He helped by giving ammunition to the troops. These troops were organized to fight the invasion. The British were defeated in August 1806. But they came back a year later. Rosas then joined a cavalry militia. However, he was probably too sick to fight actively.

Life as a Rancher

After the British invasions were stopped, Rosas and his family moved to their estancia (ranch). Working there helped shape his personality. In the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, large landowners like the Rosas family provided food and protection. They also had private defense forces. These forces were mostly made up of their workers, called peons, who were often gauchos.

Landowners of Spanish descent often looked down on the gauchos. Gauchos were mostly illiterate and of mixed race. They were seen as hard to control. But they were tolerated because there were no other workers. Rosas got along well with the gauchos who worked for him. He was strict, but he dressed like them and joked with them. He also paid them well. However, he always made sure they knew he was in charge. Rosas was a conservative person. He believed in order and authority, like other big landowners.

Rosas learned a lot about managing ranches. In 1811, he started managing his family's estancias. In 1813, he married Encarnación Ezcurra. She was from a wealthy family in Buenos Aires. Soon after, he started his own career. He produced salted meat and bought more land. Over the years, he became a successful estanciero (rancher) himself. He partnered with his cousins, the powerful Anchorena family. His hard work and good organization helped him succeed.

Becoming a Powerful Leader

The Rise of a Caudillo

The May Revolution of 1810 led to Argentina's independence from Spain. Rosas and other landowners were wary of this movement. It was mainly led by people in the city of Buenos Aires. Rosas was especially upset when Viceroy Santiago de Liniers was executed by the revolutionaries. Rosas missed the colonial times, which he saw as stable and orderly.

When Argentina declared full independence from Spain in July 1816, Rosas accepted it. But independence caused the old Viceroyalty to break apart. Buenos Aires province then fought a civil war with other provinces. They argued about how much freedom provincial governments should have. The Unitarian Party wanted Buenos Aires to be the most powerful. The Federalist Party wanted provinces to be more independent. This conflict lasted for ten years. In 1820, Rosas and his gauchos joined the army of Buenos Aires. They wore red and were called "Colorados del Monte" ("Reds of the Mount"). They fought off invading provincial armies and saved Buenos Aires.

After the conflict, Rosas returned to his ranches. He had gained respect for his military service. He was promoted to cavalry colonel and given more land by the government. These new lands, along with his successful business, made him very rich. By 1830, he was one of the biggest landowners in Buenos Aires province. He owned 300,000 cattle and 420,000 acres of land. With his new power, military background, and loyal gaucho army, Rosas became a powerful caudillo.

First Time as Governor

Argentina faced constant civil wars and rebellions. The fight between Unitarians and Federalists caused a lot of instability. By 1826, Rosas had built a strong group of supporters. He joined the Federalist Party. He cared most about his home province of Buenos Aires. In 1820, he fought with the Unitarians because he saw the Federalist invasion as a threat to Buenos Aires. But later, when Unitarians wanted to share customs money from Buenos Aires with other provinces, Rosas saw this as a threat to his province.

In 1827, four provinces led by Federalist leaders rebelled. Rosas helped the Federalists take over Buenos Aires. He also helped elect Manuel Dorrego as provincial governor. Rosas was given the job of general commander of the rural militias. This made him even more powerful.

In December 1828, Juan Lavalle, a Unitarian governor, captured and executed Dorrego. Rosas then became the main Federalist leader. He rebelled against the Unitarians. He teamed up with Estanislao López, another powerful leader. They defeated Lavalle in April 1829. When Rosas entered Buenos Aires in November, people cheered him. He was seen as a war hero and the Federalist leader. Rosas was described as handsome, tall, with blond hair and "piercing blue eyes." Charles Darwin, who met Rosas, called him "a man of extraordinary character."

On December 6, 1829, the Buenos Aires House of Representatives elected Rosas as governor. They gave him "extraordinary powers." This was the start of his rule, which historians call a dictatorship. He saw himself as a good dictator. He said he wanted to serve his country. He used his power to silence critics and send enemies away. He said he found the government in chaos when he took over.

The Desert Campaign

Rosas's first time as governor focused on fixing money problems. His government had big debts and the money was losing value. A severe drought also hurt the economy. The Unitarians still controlled some provinces. But the capture of their leader, José María Paz, in March 1831 ended the civil war. Rosas agreed to let provinces have more freedom in the Federal Pact. To help the government's finances, he collected more money without raising taxes. He also cut spending.

By the end of his first term, Rosas was praised for bringing stability. But he faced more opposition in the House of Representatives. All members were Federalists, but some wanted a constitution. Rosas did not want to be limited by a constitution. He gave up his dictatorial powers unwillingly. His term ended on December 5, 1832.

While Buenos Aires was busy with politics, ranchers moved into lands where native peoples lived. This caused conflict. Rosas supported this expansion. He gave land in the south to war veterans and ranchers. The south was seen as a desert, but it had potential for farming and ranching. The government gave Rosas an army to control the Indian tribes in this area. Rosas was kind to Indians who surrendered, giving them animals and goods. But he hunted down those who refused to give up. The Desert Campaign lasted from 1833 to 1834. Rosas took control of the entire region. This conquest opened up new areas for Argentina.

Rosas's Second Rule

Taking Absolute Power

While Rosas was away on the Desert Campaign, his supporters took control of Buenos Aires in October 1833. Rosas's wife, Encarnación, helped them. This event was called the Revolution of the Restorers. It forced the provincial governor, Juan Ramón Balcarce, to resign. Two other weak governments followed him. Rosas's supporters, called Rosistas, became very powerful. They pushed for Rosas to return with full dictatorial powers. They said it was the only way to bring back stability. The House of Representatives agreed. On March 7, 1835, Rosas was reelected governor. He was given the "suma del poder público" (total public power).

A vote was held to see if people supported Rosas's return and his dictatorial powers. During his first term, Rosas had already made elections unfair. He put loyal friends in charge of local offices. These officials controlled tax collection, militias, and elections. They kept voters away and scared the opposition. This way, Rosas always got the results he wanted. Half of the House of Representatives members were reelected each year. Rosas quickly removed any opposition through rigged elections. This allowed him to control the legislature. The legislature also lost control over money. It became a mere formality to approve his laws. The 1835 election result was a predictable 99.9 percent "yes" vote.

Rosas believed that controlling elections was needed for political stability. Most people in the country could not read or write. He gained total power with the support of most landowners and businessmen. His ranches were the base of his power. Historian John Lynch said that Rosas was at the center of a large family group. This group included deputies, officials, and military leaders who were also landowners and related to him.

A Controlling Government

Rosas's power went far beyond the House of Representatives. He controlled the government workers and his cabinet very strictly. He said his ministers were just his secretaries. He rewarded his supporters with government jobs. Anyone he saw as a threat was removed. Newspapers that opposed him were publicly burned. Rosas created a "cult of personality." He presented himself as an all-powerful, father-like figure who protected the people. His pictures were carried in street parades and placed in churches. Rosismo (Rosism) became a strong political movement. Rosas once said he was not a Federalist, but he used Federalism to gain power.

Rosas created a very controlling government. It tried to control every part of public and private life. All official documents had to start with the slogan: "Death to the Savage Unitarians." Everyone who worked for the state had to wear a red badge. It said: "Federation or Death." Men had to have a "federal look," meaning a big mustache and sideburns. Many even wore fake mustaches. The color red, which symbolized Rosas's party, was everywhere in Buenos Aires. Soldiers wore red clothes and their horses had red gear. Civilians also had to wear red. Buildings were decorated in red too.

Most Catholic priests in Buenos Aires supported Rosas. The Jesuits were the only ones who refused, so they were expelled from the country. Poor people in Buenos Aires did not see their lives improve. Rosas cut spending on education, social services, and public works. Land taken from Indians and Unitarians was not given to rural workers. Black people also did not see better conditions. Rosas owned slaves and helped bring back the slave trade. Even so, he remained popular among black people and gauchos. He hired black people and attended their celebrations. Gauchos admired his leadership and how he sometimes socialized with them.

Using Fear to Rule

Besides removing people and censoring, Rosas used other methods against his opponents. Historians call these methods "state terrorism." Fear was a tool to silence those who disagreed. It also helped him keep his supporters loyal and get rid of enemies. People were accused, sometimes wrongly, of being linked to Unitarians. Even members of his own government were targeted if they were not loyal enough. If real opponents were not found, the government found other people to punish as an example. This created a climate of fear. People had to follow Rosas's orders without question.

The Mazorca carried out this state terrorism. It was an armed police unit of the Sociedad Popular Restauradora political group. Rosas created and controlled both the Sociedad Popular Restauradora and the Mazorca. The mazorqueros would search houses and scare people. They arrested, tortured, and killed others. Modern estimates say about 2,000 people were killed between 1829 and 1852.

Even though a court system existed, Rosas took away its independence. He controlled who became judges or simply ignored the courts. He would judge cases himself. He gave out punishments like fines, army service, jail, or execution. Only Rosas could use state terror. His helpers had no control over it. It was used against specific targets, not randomly. Terrorism was planned, not just angry mobs. Rosas wanted law and order, so he did not allow uncontrolled violence. Foreigners were safe from abuse. Very poor or unimportant people were also safe, as they could not serve as good examples. Victims were chosen to create fear.

Challenges and Dominance

Rebellions and Outside Threats

From the late 1830s to the early 1840s, Rosas faced many big threats. The Unitarians found an ally in Andrés de Santa Cruz, who ruled the Peru–Bolivian Confederation. Rosas declared war on them on March 19, 1837. This was part of the War of the Confederation. Rosas's army played a small role. The war ended with Santa Cruz being overthrown. On March 28, 1838, France blocked the Port of Buenos Aires. They wanted to gain more influence in the region. Rosas could not fight the French directly. So, he increased control inside Argentina to stop uprisings.

The blockade badly hurt the economy of all provinces. They exported their goods through Buenos Aires. Despite the 1831 Federal Pact, provinces were unhappy with Buenos Aires's power. On February 28, 1839, the province of Corrientes revolted. They attacked Buenos Aires and Entre Ríos. Rosas fought back and defeated the rebels. Their leader, the governor of Corrientes, was killed. In June, Rosas found a plot by some of his own supporters to remove him. This was called the Maza conspiracy. Rosas jailed some plotters and executed others. Manuel Vicente Maza, a high-ranking official, was murdered by Rosas's Mazorca agents. This happened inside the parliament. They claimed his son was involved in the plot. In the countryside, landowners, including Rosas's younger brother, rebelled. This started the Rebellion of the South. The rebels tried to get help from France. But they were easily crushed. Many lost their lives and property.

In September 1839, Juan Lavalle returned after ten years away. He joined with the governor of Corrientes, who rebelled again. Lavalle invaded Buenos Aires province with Unitarian troops. France supplied these troops. Encouraged by Lavalle, other provinces also rebelled. These included Tucumán, Salta, La Rioja, Catamarca, and Jujuy. They formed the Coalition of the North. Great Britain then helped Rosas. France lifted its blockade on October 29, 1840. The fight against his internal enemies was tough. By December 1842, Lavalle was killed. The rebellious provinces were defeated, except Corrientes. Corrientes was finally defeated in 1847. Rosas's forces also used terror on the battlefield. They refused to take prisoners.

Ruler of All Argentina

Around 1845, Rosas gained complete control over the region. He controlled all parts of society with strong army support. Rosas was promoted to brigadier general, the highest army rank, in 1829. He later refused the even higher rank of grand marshal. The army was led by officers who shared his background and values. Feeling confident, Rosas made some changes. He returned confiscated properties to their owners. He also disbanded the Mazorca and stopped torture and political killings. People in Buenos Aires still followed Rosas's rules for dress and behavior. But the constant fear greatly lessened.

When Rosas was first elected governor in 1829, he had no power outside Buenos Aires province. There was no national government. The old Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata had become the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. By 1831, it was known as the Argentine Confederation, or simply Argentina. Rosas's victories over other Argentine provinces in the early 1840s made them dependent on Buenos Aires. He slowly put governors in place who were either allies or too weak to be truly independent. This allowed him to control all the provinces. By 1848, Rosas started calling his government the "government of the confederacy." The next year, with the provinces' agreement, he named himself "Supreme Head of the Confederacy." He became the undisputed ruler of Argentina.

As Rosas got older and his health declined, people wondered who would take his place. His wife, Encarnación, had died in 1838. Rosas was very sad, but he used her death to gain more support. Later, he had five children with his fifteen-year-old maid. Rosas had two children with Encarnación: Juan Bautista Pedro and Manuela Robustiana. Rosas wanted his children from his marriage to succeed him. He said they were worthy and capable. It is not known if Rosas secretly wanted a monarchy. Later, in exile, he said that Princess Alice of the United Kingdom would be a good ruler for Argentina. However, in public, he always said his government was a republic.

End of His Rule

Blocking the Ports

The old Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata broke apart in the 1810s. This led to the independent nations of Paraguay, Bolivia, and Uruguay. The southern parts became the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (Argentina). Rosas wanted to bring back much of the old Viceroyalty's territory. He never accepted Paraguay's independence. He saw it as a rebellious Argentine province that would be retaken. He sent an army under Manuel Oribe to invade Uruguay. Oribe conquered most of Uruguay, except its capital, Montevideo. Montevideo faced a long siege starting in 1843. When the British asked, Rosas refused to promise Uruguay's independence. Other foreign threats to Rosas's plans in South America had collapsed or were facing their own problems. To strengthen his claims over Uruguay and Paraguay, Rosas blocked the port of Montevideo. He also closed the interior rivers to foreign trade.

Britain and France did not like losing trade. On September 17, 1845, they started the Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata. They forced open navigation in the Río de la Plata Basin. Argentina resisted this pressure and fought back. This undeclared war hurt France and Britain more than Argentina. The British realized that new trade access did not make up for the loss of trade with Buenos Aires. Britain ended hostilities and lifted the blockade on July 15, 1847. France followed on June 12, 1848. Rosas had successfully resisted the two most powerful nations. His standing, and Argentina's, grew among other Latin American nations.

Even though his reputation was high, Rosas did not make his rule much freer. Every year, he offered to resign. But the House of Representatives always refused, saying he was vital for the nation. Rosas also allowed exiled Argentines to return. But he was so confident in his control that no one dared to challenge him. In August 1848, a woman named Camila O'Gorman was executed. This caused a lot of anger across the continent. It showed that Rosas had no plans to loosen his grip on power.

The Platine War and Downfall

Rosas did not realize that people were becoming more and more unhappy. In the 1840s, he became more isolated in his country house in Palermo. He ruled from there, protected by many guards. He stopped meeting with his ministers and relied only on secretaries. His daughter Manuela became his main link to the outside world. A member of his staff said Rosas was isolated because he knew people hated him. He was always afraid and ready to escape.

Meanwhile, Brazil, now strong under Emperor Pedro II, helped the Uruguayan government. Uruguay was still holding out in Montevideo. Brazil also supported Justo José de Urquiza, a powerful leader in Entre Ríos. Urquiza rebelled against Rosas. Urquiza had once been one of Rosas's most trusted helpers. Now, he claimed to fight for a constitutional government. But he also wanted to become head of state. In response, Rosas declared war on Brazil on August 18, 1851. This started the Platine War. Oribe's army in Uruguay surrendered to Urquiza in October. With weapons and money from Brazil, Urquiza marched through Argentina towards Buenos Aires.

Rosas acted strangely passive during the conflict. He lost hope when he realized he was trapped. Even if he defeated Urquiza, his forces would be too weak to fight the Brazilian army. Rosas said: "There is no other way; we have to play for the high stakes and go for everything." After losing a battle against Urquiza on February 3, 1852, Rosas fled to Buenos Aires. He disguised himself and boarded a ship to Britain to live in exile. He said: "It is not the people who have overthrown me. It is the monkeys, the Brazilians."

Later Life and Legacy

Exile and Death

Rosas arrived in Plymouth, Great Britain, on April 26, 1852. The British gave him a safe place to stay. They paid for his travel and welcomed him with a 21-gun salute. These honors were given because Rosas had been kind to British merchants. Months before his fall, Rosas had arranged for protection and asylum with a British diplomat. Both his children from Encarnación went with him into exile. However, his son Juan Bautista soon returned to Argentina. His daughter Manuela married the son of an old friend of Rosas. Rosas never forgave her for this. He was a very controlling father and wanted his daughter to be devoted only to him. Even though he forbade her from writing or visiting, Manuela remained loyal and kept in touch.

The new Argentine government took all of Rosas's properties. They tried him as a criminal and sentenced him to death. Rosas was shocked that most of his friends and supporters abandoned him. They either became silent or openly criticized him. Rosismo disappeared overnight. Historian Lynch said that the landowners, who had supported Rosas, now made peace with the new leaders. Survival was more important than loyalty. Urquiza, who had been an ally and then an enemy, made up with Rosas. He sent him money, hoping for political support. But Rosas had little political power left. Rosas followed Argentina's news from exile. He always hoped to return, but he never got involved in Argentine affairs again.

In exile, Rosas was not poor, but he lived simply. A few loyal friends sent him money, but it was never enough. He had sold one of his ranches before it was taken by the government. He became a tenant farmer in Swaythling, near Southampton. He hired a housekeeper and a few workers. He paid them good wages. Despite worrying about money, Rosas enjoyed farm life. He once said he was happy living modestly and earning a living by hard work. A person who knew him later in life said he was still handsome and impressive at eighty. His manners were refined, and he still had the air of a great lord. After a walk on a cold day, Rosas caught pneumonia. He died at 7:00 AM on March 14, 1877. After a private mass, he was buried in the town cemetery of Southampton.

Rosas's Place in History

People started to look at Rosas's reputation differently in the 1880s. Scholars like Adolfo Saldías and Ernesto Quesada published new works. Later, a more open "Revisionist" movement grew under Nacionalismo (Nationalism). Nacionalismo was a political movement in Argentina that became strong in the 1930s. It was similar to other authoritarian ideas at that time, like Nazism and Fascism. Argentine Nationalism supported ideas like eugenics. Revisionismo (Revisionism) was the history part of Argentine Nacionalismo. The main goal of Nacionalismo was to create a national dictatorship. For this movement, Rosas and his rule were seen as perfect examples of good government. Revisionismo helped by trying to improve Rosas's image.

Despite many years of effort, Revisionismo was not taken seriously by most scholars. According to Michael Goebel, the revisionists did not care much about scholarly standards. They also never changed the main views about Rosas. In 1930, William Spence Robertson said Rosas was a "gigantic and ominous figure" who ruled for over twenty years. He said Rosas's power was so strict that Argentines called his time "The Tyranny of Rosas." In 1961, William Dusenberry said Rosas was a "negative memory" in Argentina. He said there were no monuments, parks, or streets named after him.

In the 1980s, Argentina was divided. It had faced military dictatorships, economic problems, and a defeat in the Falklands War. President Carlos Menem decided to bring Rosas's remains back to Argentina. He hoped this would help unite the country. Menem believed that if Argentines could forgive Rosas, they might also forgive more recent difficult times. On September 30, 1989, a large ceremony was held. Rosas's remains were buried in his family vault at La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires. Menem and later presidents have honored Rosas on banknotes, stamps, and monuments. This has caused mixed reactions among the public. Rosas remains a controversial figure in Argentina. Historian John Lynch noted that Argentines "have long been fascinated and outraged" by him.

Images for kids

-

Gauchos resting in the pampas. Oil painting by Johann Moritz Rugendas.

-

Gauchos hunting feral horses. They served in the private army of Rosas.

-

Rosas (seated, left) watching a Candomble celebration, 1845.

-

Rosas' family vault at La Recoleta Cemetery.

-

Sculpture with the image of Rosas at the Monument to the Battle of Vuelta de Obligado.

See also

In Spanish: Juan Manuel de Rosas para niños

In Spanish: Juan Manuel de Rosas para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |