Caudillo facts for kids

A caudillo (say: kaw-DEE-yoh) is a special kind of leader who has both military and political power. There isn't one perfect English word for caudillo, but it's like calling someone a very powerful leader or a military chief. This term is mostly used for leaders in Spain and Latin America, especially after these countries became independent in the early 1800s.

The idea of a caudillo might have started in Spain a long time ago, during the Reconquista, when Spanish Christians fought to take back land from the Moors. Spanish conquistadors like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro were a bit like caudillos. They were successful military leaders who relied on their supporters and rewarded them for their loyalty.

During the time when Spain ruled the Americas, the Spanish government had many rules and systems that stopped individual leaders from becoming too powerful. But after the Spanish American wars of independence in the early 1800s, the old colonial rule ended. This left a big power gap. Caudillos then became very important in the history of Latin America. They have even influenced political groups today.

Sometimes, people use the word caudillo to criticize a leader. However, General Francisco Franco of Spain (who ruled from 1936 to 1975) proudly used the title for himself after he took power in the Spanish Civil War. Caudillos often ruled in a way that meant they had a lot of control and didn't share power much. Many societies have had strong leaders, but Latin America has had many, even if they didn't all call themselves caudillos.

Contents

Powerful Leaders in Latin America

Since Latin American countries became independent in the early 1800s, the region has been known for its many caudillos and how long they ruled. The early 1800s is sometimes called "The Age of Caudillos." During this time, leaders like Juan Manuel de Rosas in Argentina and Antonio López de Santa Anna in Mexico were very dominant. Brazil became independent as an empire, which helped keep its country together and its government strong.

In Spanish America, new countries were often weak. This allowed caudillos to keep ruling from the late 1800s into the 1900s. In Mexico, the creation of the Institutional Revolutionary Party in 1929 helped end the era of caudillos. But strong leaders, sometimes called caudillos, have ruled in many other countries. These include Cuba (Gerardo Machado, Fulgencio Batista, Fidel Castro), Panama (Omar Torrijos, Manuel Noriega), the Dominican Republic (Desiderio Arias, Cipriano Bencosme), Paraguay (Alfredo Stroessner), Argentina (Juan Perón and other military leaders), and Chile (Augusto Pinochet). Caudillos have also been important characters in books from Latin America.

Latin America isn't the only place where strong leaders appear during difficult times. But in Spanish America, it happened a lot because the Spanish colonial government broke down after the wars for independence. The leaders who fought in these wars often became the new rulers. Historian John Lynch said that before 1810, caudillos were not known. He explained that a caudillo started as a local hero who became a military chief because of bigger events. They gained power by being successful military leaders.

In rural areas where there was no strong government, and where there was often conflict, a caudillo could bring order. They often used force to do this. To keep their power, they had to make sure their followers stayed loyal. So, they would give rewards to their supporters. Caudillos could also stay in power by protecting the interests of rich and powerful families. A local strong leader who built a base in his region could then try to become a national caudillo and take control of the whole country. When this happened, caudillos could give jobs and favors to many people, who in turn supported them. Generally, the power of caudillos helped the wealthy. But these strong leaders also acted as a link between the rich and the common people. They would bring common people into their power base but also stop them from gaining too much power themselves.

Some strong leaders, called "folk caudillos" by historian E. Bradford Burns, came from humble backgrounds. They often protected the interests of native groups or other poor rural people. They were different from the rich, European-style leaders who looked down on the common people. Examples include Juan Facundo Quiroga and Juan Manuel de Rosas in Argentina, who were popular leaders. Burns believes that the negative view of caudillos often comes from city elites who didn't understand or respect the followers of these folk caudillos.

National caudillos often tried to make their rule seem official by using titles like "President of the Republic." If the country's rules (constitution) limited how long a president could serve, caudillos might bend or break these rules to stay in power. This practice was called "continuismo."

Caudillos could have different political ideas, either liberal or conservative. After independence, liberal ideas were popular. They were based on the ideas of the independence heroes and helped create the new countries' rules. Free trade was a common economic idea. Many new countries chose a federal system, where regions had more power. However, this sometimes led to countries breaking apart and having weak central governments.

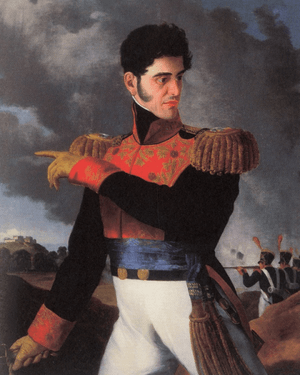

Conservative caudillos also appeared around 1830. Many new countries rejected the old colonial ways, but the Roman Catholic Church and traditional values remained strong in many areas. Rich families supported these values to keep their power. Conservative caudillos, with the support of the Church and elites, worked to create strong central governments. In Argentina, Juan Manuel de Rosas, and in Mexico, Antonio López de Santa Anna, were examples of conservative leaders who ruled with great power.

Independence Era Leaders

The Spanish American wars of independence in the early 1800s caused big changes in Spain and its empire. In 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Spain, removed the Spanish king, and put his brother Joseph on the throne. Napoleon himself was a successful general who rose to power during the French Revolution. For Spain and its empire, losing their rightful king led to many changes.

In Spanish America, the Spanish government had already made changes that kept American-born Spaniards (called criollos) from holding important political jobs. They also put in place economic rules that hurt some parts of the empire. Before this, Spanish America had some local rule, and local leaders could get official jobs.

Napoleon's invasion of Spain caused Spanish American regions to seek more control. Many areas set up local governments (called juntas) in the name of the removed Spanish king. When Ferdinand VII was put back on the Spanish throne in 1814 and tried to rule with absolute power, the fights in many parts of Spanish America became full wars for independence. By 1825, most of Spanish America, except for Cuba and Puerto Rico, had become independent.

Some independence leaders hoped that the new countries would be like the old Spanish viceroyalties (large colonial areas), but with local control. The Roman Catholic Church remained strong, as did the armies that won against the Spanish forces. However, the new governments in most areas were weak. There were many disagreements about what kind of government the new nations should have. Veterans of the independence wars often saw themselves as the rightful leaders of the new countries.

After the violence and political chaos, the new nations faced destroyed property, lost trade, and governments that lacked real power. The first few decades after independence saw the rise of strong leaders who came from the military. Spanish America had only known monarchy (rule by a king or queen). Mexico even tried to set up an empire under a former Spanish general, Agustín de Iturbide. Brazil became independent as the Brazilian Empire, which kept its territory together and was ruled by a king.

In Spanish America, the new independent states struggled to balance a strong central government, usually controlled by traditional powerful families, with some way for the new "citizens" to have a say. Constitutions were written that divided power, but strong individual leaders, caudillos, often dominated. Some caudillos were given great powers, even if they were technically ruling as presidents under a constitution. They were sometimes called "constitutional dictators."

Key Leaders of the Independence Time

Early 1800s Caudillos

Some strong leaders went beyond just fighting for power and created "integrative dictatorships." These governments tried to stop regions from breaking away and instead made the central government very strong. Political scientist Peter H. Smith says these leaders included Juan Manuel de Rosas in Argentina, Diego Portales in Chile (whose system lasted almost a century), and Porfirio Díaz in Mexico. Rosas and Díaz were military men who continued to use armed forces to stay in power.

Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean

This region was often influenced by stronger countries like the United States and the United Kingdom. Cuba remained a Spanish colony until 1898. The United States took a large part of Mexico's territory. Britain tried to set up a protectorate (a controlled area) on the Mosquito Coast of Central America. The two most powerful leaders in this early century were Antonio López de Santa Anna in Mexico and Rafael Carrera in Guatemala.

The liberal leader Francisco Morazán is seen as one of the most important figures for Central American independence and unity. Morazán was known as a great thinker. He made many liberal changes in the Federal Republic of Central America, such as freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of religion. He also limited the power of the church by making marriage a civil ceremony and ending government-supported church taxes.

Mexico started its fight against Spain in 1810 and became independent in 1821. After independence, political groups were divided. Federalists wanted a weak central government and were often linked to liberal ideas. Centralists wanted a strong central government and protected traditional groups like the Mexican Army and the Catholic Church. Many regional strong leaders were Federalists, supporting local control and their own power. The most famous Mexican caudillo, Antonio López de Santa Anna, gained national power for decades. He started as a Liberal but became a Conservative, wanting a stronger central government.

After the Mexican–American War, regional caudillos like Juan Álvarez from Guerrero and Santiago Vidaurri from Nuevo León-Coahuila removed Santa Anna from power. This brought Liberals to power. General Juan Álvarez was a "folk caudillo" who protected the mostly native and mixed-race farmers of Guerrero. They, in turn, were loyal to him. Álvarez briefly served as President of Mexico, then returned to his home state, allowing other liberals to start the era of La Reforma (The Reform).

During the Mexican Reform and the French intervention, many generals had local followers. Important figures whose local power affected the whole country included Mariano Escobedo in San Luis Potosí, Ramón Corona in Jalisco and Durango, and Porfirio Díaz in parts of Veracruz, Puebla, and Oaxaca. Other caudillos had more local power but were still important. After the French were defeated in 1867, the governments of Benito Juárez and his successor, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, faced opposition. These opponents supported Porfirio Díaz, a military hero, who challenged Juárez and Lerdo. Díaz's second rebellion was successful in 1876.

Bolivarian Republics: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela

Simón Bolívar, the most important independence leader in Spanish America, tried to create a large nation called Gran Colombia from the old Viceroyalty of New Granada. But like other parts of Spanish America, different regions wanted to be separate. So, despite Bolívar's leadership, the country broke into separate nations. Bolívar saw the need for political stability. He thought a president who ruled for life and could choose his successor would help. In 1828, his supporters asked him to take full power to "save the republic." However, the political problems continued, and Bolívar stepped down in 1830. He went into exile and died soon after. He is honored as the person who contributed the most to Spanish American independence.

Veterans of the independence wars became the leaders of the new nations, each with a new constitution. Despite these constitutions and political labels like Liberal and Conservative, individual leaders who often sought their own gain dominated the early 1800s. Like Mexico and Central America, the political problems and lack of money in these new governments stopped foreign investors from putting their money there.

One caudillo who was very forward-thinking for his time was Bolivia’s Manuel Isidoro Belzu. He was Bolivia's president from 1848 to 1855. Belzu took power in 1848 and became president by stopping a counter-rebellion. During his time as president, Belzu made several changes to the country's economy to share wealth more fairly. He rewarded the hard work of the poor and those who had lost their land. Like Paraguay’s José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia, Belzu put in place programs to help the poor. This was because the idea of sharing things was more in line with the traditional values of native people than the idea of private property that other caudillos supported.

Belzu also took control of Bolivia's profitable mining industry. He put in place rules to keep Bolivian resources for Bolivian use. This made powerful British, Peruvian, and Chilean shipping and mining companies angry. Many of Belzu’s policies made him popular among Bolivia's long-suffering native peoples. But this also angered wealthy Bolivians and foreign countries like Britain. Belzu even took steps to make his leadership official and was once democratically elected. Despite his popularity, Belzu had many powerful enemies. He survived 40 assassination attempts! His enemies wanted to destroy the state-run projects that helped his nationalist plan and improved public life for the country's poor.

However, Belzu also showed the harsh side of caudillo rule. From the early 1850s until he left power in 1855, he is said to have ruled with great power and became very rich. Belzu thought about returning to the presidency in 1861, but he was shot by one of his rivals when he tried to run again. He couldn't leave a lasting impact, and his programs for the people ended with him. After Bolivia's independence, it lost half of its land to neighboring countries like Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Brazil through wars and agreements made under threat.

Southern Cone: Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay

Unlike most of Spanish America, Chile had political stability after independence. This was under the strong rule of Conservatives, supported by landowners. Although he never became president, cabinet minister Diego Portales (1793–1837) is credited with creating a strong, central government that lasted 30 years. Chile generally did well with an economy focused on exporting farm products and minerals, which was unusual for most Spanish American countries.

In the area of the former viceroyalty of Río de la Plata, political problems and violence were more common. In Argentina, Juan Manuel de Rosas (ruled 1829–1852) controlled the Argentine confederation. He came from a rich landowning family but also bought large areas of land in Buenos Aires province. Rosas disliked "the ideas of political democracy and freedom" but he brought order to a region that had been very chaotic since independence. This order came at the cost of harshly stopping his enemies, using various armed followers, most famously the Mazorca. He was popular among the common people in Buenos Aires province.

During his two decades in power, Rosas became a very powerful leader. He became the example of what a caudillo was supposed to be. He used his military experience to get support from cowboys (gauchos) and ranchers to create an army that challenged Argentina's leadership. After gaining power using rural workers, he changed his system to rely more on the military. He tried to ban imported goods to help artisans in Argentina, but he failed. He had to lift the ban on some imports, like textiles, which opened trade with Great Britain. Through his control over imports and exports, the military, the police, and even the law-making part of the government, Rosas created a system that kept him in power for over two decades. However, these weren't peaceful years. By the 1850s, Rosas was being attacked by the very people who had helped him gain power. He was forced out of power and eventually went to Great Britain, where he died in 1877.

Uruguay became independent from Brazil and Argentina and was ruled by Fructuoso Rivera. In Paraguay, José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (ruled 1814–1840) was the Supreme Dictator of the Republic. He kept the country, which had no access to the sea, independent from Argentina and other foreign powers. Cut off from outside trade, Paraguay became economically self-sufficient under Francia. He based society on shared property, rather than a strong central government, trying to go back to the ways of the native Indian communities that existed before in Paraguay.

After independence, the government took control of land that was once owned by the Church and the Spanish state. Francia created state-run farms and rented out land to citizens who could pay a fee. Francia's strict rules included breaking the power of the rich American-born Spaniards and limiting the power of the Roman Catholic Church. Francia allowed religious freedom and ended the church tax. He actively encouraged people from different backgrounds to marry. He has been a debated figure in Latin American history, as he tried to help the poor. Many modern historians say he brought stability to Paraguay, kept it independent, and left behind "an equal, unified nation." However, because he cracked down on the wealthy elite and weakened their power, he was accused of being against the church. Nevertheless, Paraguay did well under Francia in terms of economy and trade through a route with Buenos Aires, which wealthy Argentinian elites opposed. Some call him a dictator, but modern history sees Francia as an honest, popular leader who helped his war-torn country become economically strong and independent.

Gallery

-

Facundo Quiroga, Argentina

-

Diego Portales, Chile

-

Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera, Colombia

-

Pedro Santana, Dominican Republic

-

Juan José Flores, Ecuador

-

Rafael Carrera, Guatemala

-

José Trinidad Cabañas, Honduras

-

José María Morelos, Mexico

-

Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia, Paraguay

-

Agustín Gamarra, Peru

-

José Antonio Páez, Venezuela

Caudillos in the Late 1800s and 1900s

In the late 1800s, governments in Latin America became more stable and were often less controlled by military men. Foreign investors, especially from Britain, started building important things like railways, telegraph lines, and port facilities. These projects made transportation faster and cheaper and improved communication. Stable governments were needed to protect these foreign investments and help get resources and farm products. Factories also started in some countries (Mexico, Argentina, Colombia) to make goods locally.

Generally, foreign governments and businesses didn't want to directly rule Latin American countries as colonies. They were happy as long as their interests were helped by modernizing national governments. This was often called neocolonialism, meaning new forms of control. There are many examples of continuismo in Latin America, where presidents stayed in office longer than allowed by law. They did this by changing the rules, holding special votes, or creating family dynasties, like the Somoza family in Nicaragua.

Mexico

A major example of a modernizing caudillo in the late 1800s is General Porfirio Díaz (ruled 1876–1911). His time in power is known as the Porfiriato. His motto was “order and progress.” This was enforced by armed men controlled by the president, called the Rurales. Díaz didn't want to depend on the Mexican army because, as a general who led a rebellion himself, he knew they could interfere in national politics. Díaz either brought regional opponents into his side or crushed them, creating a political system to achieve his vision for a modern Mexico.

Díaz wanted economic development that needed foreign investment. He sought money and experts from European countries (Britain, France, and Germany) to balance the closer power of the United States. Although elections were held regularly in Mexico, they were not truly democratic. The large rural, uneducated, and mostly native populations were more feared by the government than seen as a source of support. When Díaz couldn't find a good way to choose his successor, the Mexican Revolution broke out after the unfair 1910 election.

Díaz came to power through a rebellion and was president of Mexico from 1876 to 1880. His military and political friend Manuel González succeeded him (1880–1884). Díaz then returned to the presidency until he was overthrown in 1911 during the Mexican Revolution.

During that ten-year civil war, many regional caudillos appeared. Pascual Orozco helped remove Díaz early in the Revolution but then turned against Francisco I. Madero, who became president in 1911. Pancho Villa also helped remove Díaz, supported Madero, and after Madero's death in 1913, became a general in the Constitutionalist Army. Emiliano Zapata, a peasant leader from Morelos, opposed Díaz and every Mexican government after him until he was killed in 1919. Álvaro Obregón became another brilliant general from northern Mexico, defeating Villa's army in 1915. Obregón and fellow generals Plutarco Elías Calles and Adolfo de la Huerta overthrew the government in 1920. In the 1920s, the presidency went from de la Huerta, to Obregón, to Calles, and back to Obregón.

During Calles's presidency (1924–28), he strictly enforced laws against the church from the Mexican Constitution of 1917. This led to the Cristero War, a major uprising led by some regional caudillos. Obregón was elected again in 1928 but was killed before he could become president again. In 1929, Plutarco Elías Calles started a political party, which later became the Institutional Revolutionary Party. He became the "Jefe Máximo" (maximum chief), holding the real power behind the presidency from 1928 to 1934. This party controlled Mexican politics until 2000 and helped limit the power of individual regional caudillos in Mexico.

Central America

With better transportation, tropical products like coffee and bananas could be sent to a growing market in the United States. In Guatemala, Justo Rufino Barrios ruled as a liberal leader with strong control and expanded coffee farming. In El Salvador, Santiago González took power in 1871 and established liberal rule until 1944. In Nicaragua, José Santos Zelaya removed conservatives in 1893 and started agricultural exports and building projects. He later became unfriendly to the United States, which helped remove him in 1909. With the creation of the United Fruit Company in the U.S. in 1899, the company's presence in Latin America grew, especially in Costa Rica, Guatemala, Colombia, and Cuba.

In 20th-century Nicaragua, the powerful leader Anastasio Somoza García held the presidency and was then followed by his son Anastasio Somoza Debayle, creating a political family rule. This was a very strict government, supported by the United States to keep stability and protect U.S. business interests. The Somoza family rule was overthrown in the Sandinista Revolution in 1979.

Caribbean

Cuba was a Spanish colony until the Spanish–American War (1898). So, caudillos only came to power there in the 1900s. Gerardo Machado and Fulgencio Batista came from the Cuban military. Machado ran for re-election in 1928 even though he promised to serve only one term. He became very harsh against his critics. Machado was overthrown in 1933, and Batista rose to power. Batista made himself head of the armed forces, ruled through other presidents, and was elected president in 1940. After failing to be re-elected in 1952, Batista led a rebellion, setting up a government that favored American businesses, landowners, and the Cuban elite.

Batista's government was overthrown in 1959 by Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro, Che Guevara, and their left-wing movement. After relations with the US got worse, leading to the Bay of Pigs Invasion in 1961, Fidel declared himself a communist and set up a government with strong control. Fidel's brother Raúl became leader in 2011 when Fidel was too ill to continue. This kind of family succession is another example of continuismo.

In the Dominican Republic, Rafael Trujillo came to power in 1930. He ruled for over 31 years as a powerful military leader, either directly or through other presidents he controlled. Trujillo created a strong image of himself, extended his harsh policies to neighboring countries, and ordered a terrible event where many Haitians were killed.

Southern Cone

Argentina has a long history of caudillo-like leaders. In the 1900s, Juan Perón and his energetic wife, Evita Perón, held power. Some historians have wondered if Evita Perón could be considered a caudilla herself. After Eva's death in 1952, Perón lost power and went into exile. He returned to power with his third wife Isabel Perón, whom he made vice president. When he died, she became president but was later overthrown by the Argentine military.

Today, the term caudillo is still used in Argentina in a negative way to describe very powerful provincial governors. These governors might stay in power for decades and be involved in corruption, especially misusing public money. They also tend to give jobs to family members. Some powerful governors called caudillos include Gildo Insfran, governor of Formosa since 1995, and Carlos Juárez in Santiago del Estero.

In the late 1800s and 1900s, Chile had a long period of civilian, constitutional rule. But when socialist Salvador Allende was elected, the Chilean Army, with support from the U.S. government, overthrew him in a rebellion on September 11, 1973. General Augusto Pinochet then took power. Pinochet tried to stay in power through legal means and held a public vote in 1988 to get popular support. The vote failed, and Chile began a period of change towards democracy.

Paraguay was ruled by General Alfredo Stroessner from 1954 to 1989. He was removed by a military rebellion in 1989.

Gallery

-

Juan Perón, Argentina

-

Germán Busch, Bolivia

-

Augusto Pinochet, Chile

-

Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, Colombia

-

José Figueres Ferrer, Costa Rica

-

Fidel Castro, Cuba

-

Rafael Trujillo, Dominican Republic

-

Eloy Alfaro, Ecuador

-

Jorge Ubico, Guatemala

-

Tiburcio Carías Andino, Honduras

-

Pancho Villa (left) & Emiliano Zapata. Mexico

-

Anastasio Somoza García, Nicaragua

-

Omar Torrijos, Panama

-

Alfredo Stroessner, Paraguay

-

Juan Velasco Alvarado, Peru

-

José Batlle y Ordóñez, Uruguay

-

Juan Vicente Gómez, Venezuela

Caudillos in Literature

Fictional Latin American caudillos, sometimes based on real historical figures, are important in books and stories. Colombian Nobel Prize winner Gabriel García Márquez wrote two books with strong leaders as main characters: The Autumn of the Patriarch and The General in his Labyrinth, a book about Simón Bolívar. In 1946, Nobel Prize winner Miguel Ángel Asturias published El Señor Presidente, based on the life of Manuel Estrada Cabrera (1898–1920). In 1974, Augusto Roa Bastos published I, the Supreme, based on the life of Paraguayan caudillo Dr. Francia.

In Mexico, two fictional caudillos are shown in Mariano Azuela's 1916 novel Los de Abajo and Carlos Fuentes's novel The Death of Artemio Cruz. Mexican writer Martín Luis Guzmán published his novel La sombra del caudillo in 1929, which strongly criticized such powerful leaders. A unique book is Rómulo Gallegos's Doña Bárbara, which features a woman caudillo.

Images for kids

-

Equestrian statue of Tomás de Herrera

-

José Joaquín de Olmedo, Guayaquil

-

Tomás de Herrera, Isthmus of Panama

-

José Núñez de Cáceres, Spanish Haiti

-

Agustín Guzmán, Los Altos

-

Manuel Rojas Luzardo, Puerto Rico

See also

In Spanish: Caudillo para niños

In Spanish: Caudillo para niños

- List of Caudillos

- Cult of personality

- Caciquismo and Caudillismo

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |