Institutional Revolutionary Party facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Institutional Revolutionary Party

Partido Revolucionario Institucional

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| President | Alejandro Moreno Cárdenas |

| Secretary-General | Carolina Viggiano Austria |

| Senate leader | Manuel Añorve Baños |

| Chamber leader | Rubén Moreira Valdez |

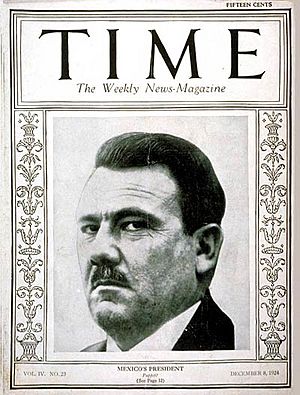

| Founder | Plutarco Elías Calles |

| Founded | 4 March 1929 (as PNR) 30 March 1938 (as PRM) 18 January 1946 (as PRI) |

| Split from | Laborist Party |

| Headquarters | Av. Insurgentes Norte 59 col. Buenavista 06359 Cuauhtémoc, Mexico City |

| Newspaper | La República |

| Youth wing | Red Jóvenes x México |

| Trade union wing | Confederation of Mexican Workers |

| Membership | 1,411,889 (2023 est.) |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Centre to centre-right |

| Continental affiliation | COPPPAL |

| International affiliation | Socialist International |

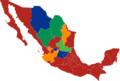

| Chamber of Deputies |

37 / 500 (7%)

|

| Senate |

14 / 128 (11%)

|

| Governorships |

2 / 32 (6%)

|

| State legislatures |

90 / 1,123 (8%)

|

|

^ A: Also described as a big tent party. |

|

The Institutional Revolutionary Party (in Spanish, Partido Revolucionario Institucional), better known as the PRI, is a major political party in Mexico. It was founded in 1929 to bring stability to the country after the Mexican Revolution. For 71 years, from 1929 to 2000, the PRI was so powerful that it won every presidential election. This long period of control is unique in modern history.

The party was created by Plutarco Elías Calles, a top leader after the revolution. He wanted to create a space where revolutionary leaders could solve problems peacefully instead of through fighting. Over the years, the party changed its name twice before becoming the PRI in 1946.

For most of the 20th century, Mexico was like a one-party state under the PRI. The party used its power to stay in control, sometimes through unfair elections or by suppressing protests. During its rule, Mexico experienced a period of great economic growth called the "Mexican miracle". This improved life for many people. However, problems like corruption and lack of freedom led to opposition.

The PRI lost the presidency for the first time in the 2000 election. It returned to power for one term from 2012 to 2018 with President Enrique Peña Nieto. Since then, the party has struggled to win major elections, receiving its worst results ever in 2018 and 2024.

Contents

History of the PRI

The PRI's story is a big part of Mexico's history. The party changed its name and ideas over time, but it always played a central role in Mexican politics.

How the Party Began (1929–1938)

After the Mexican Revolution, politics in Mexico was unstable. Leaders often fought for power. A major crisis happened in 1928 when the president-elect, Álvaro Obregón, was assassinated. This left a power vacuum.

To solve this, President Plutarco Elías Calles created a new political party on March 4, 1929. It was first called the National Revolutionary Party (PNR). The goal was to unite all the revolutionary leaders and create a peaceful way to transfer power. Instead of fighting, leaders would work within the party to choose the next president.

The first years of the party were known as the Maximato. During this time, Calles was not the president, but he was the "Jefe Máximo" (Supreme Chief) and held the real power behind the scenes.

In 1934, Calles chose Lázaro Cárdenas to be the next president. But Cárdenas had his own ideas. He became very popular with the people and challenged Calles's authority. Cárdenas eventually forced Calles out of the country and took full control of the party and the government.

A New Direction (1938–1946)

In 1938, President Cárdenas reorganized the party and renamed it the Party of the Mexican Revolution (PRM). He wanted the party to represent different groups in society. He created four main sectors:

- The labor (worker) sector

- The peasant (farmer) sector

- The popular sector (including government workers and teachers)

- The military sector

This structure, called corporatism, brought many Mexicans into the party. It helped the party stay in power for a long time by representing and controlling these major groups. Cárdenas is also famous for taking control of Mexico's oil industry from foreign companies in 1938.

When Cárdenas's term ended, he chose Manuel Ávila Camacho to be his successor. The party changed its name one last time in 1946, becoming the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

The "Perfect Dictatorship" (1946–2000)

For over 50 years, the PRI completely dominated Mexican politics. It won every presidential election, controlled the Congress, and had all the state governors. This period is sometimes called the "perfect dictatorship" because the country had elections, but the same party always won.

The Mexican Miracle

From the 1940s to the 1970s, Mexico's economy grew very fast. This period is known as the Mexican Miracle. The government invested in industry, built roads and schools, and life improved for many people. This prosperity helped the PRI stay popular and legitimized its rule.

However, not everyone benefited equally. The government also used its power to control labor unions and suppress anyone who disagreed with it.

The Tlatelolco Massacre

By the 1960s, some people, especially students, began to demand more democracy. In 1968, just before Mexico City hosted the Summer Olympics, huge student protests took place.

The government of President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz responded with force. On October 2, 1968, soldiers opened fire on a student demonstration in the Tlatelolco plaza. Hundreds of unarmed protestors were killed. This event, known as the Tlatelolco massacre, shocked the country and turned many people against the PRI. It showed that the government would use violence to keep its power.

Economic Problems and Political Change

In the 1970s and 1980s, the economic miracle ended. Mexico faced several economic crises. The government borrowed a lot of money, and when oil prices fell, the country was in deep trouble.

At the same time, opposition parties began to grow stronger. In the 1988 election, the PRI's candidate, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, won in a very controversial election. Many people believed that the opposition candidate, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas (son of Lázaro Cárdenas), had actually won, but that the results were changed. This event further weakened the PRI's reputation.

The End of an Era and a Return to Power

The 1990s were a time of great change for the PRI and for Mexico. The party's long hold on power was finally coming to an end.

Losing the Presidency (2000)

In the 2000 presidential election, for the first time in 71 years, the PRI lost. The winner was Vicente Fox from the opposition National Action Party (PAN). This was a historic moment for Mexico, marking a transition to a multi-party democracy.

For the next 12 years, the PRI was the opposition party. It had to learn how to compete in a more democratic system.

The PRI's Comeback (2012)

In the 2012 election, the PRI made a comeback. Its candidate, Enrique Peña Nieto, won the presidency. Many voters were disappointed with the PAN's performance and decided to give the PRI another chance.

Peña Nieto's government passed some important reforms, but it was also marked by scandals and accusations of corruption. His popularity fell, and many people became disillusioned with the PRI once again.

The PRI Today

In the 2018 election, the PRI had its worst result in history. Its candidate, José Antonio Meade, finished in third place. The party also lost most of its seats in Congress.

The party performed poorly again in the 2024 election. Today, the PRI is one of Mexico's main opposition parties, but it is much weaker than it was during its long rule. It faces the challenge of rebuilding trust with voters and finding its place in Mexico's modern democracy.

Images for kids

-

Álvaro Obregón's assassination in 1928 led to the party's creation.

-

Pascual Ortiz Rubio, the PNR's first presidential candidate in 1929.

-

President Manuel Ávila Camacho in 1943.

-

Miguel Alemán Valdés was the first civilian president after the revolution.

-

José López Portillo ran for president without any major opponents in 1976.

-

Miguel de la Madrid became president in 1982 during an economic crisis.

-

Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas left the PRI and ran for president in 1988.

See also

In Spanish: Partido Revolucionario Institucional para niños

In Spanish: Partido Revolucionario Institucional para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |