Álvaro Obregón facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Álvaro Obregón

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 46th President of Mexico | |

| In office 1 December 1920 – 30 November 1924 |

|

| Preceded by | Adolfo de la Huerta |

| Succeeded by | Plutarco Elías Calles |

| President of the Mexican Laborist Party | |

| In office 1918–1924 Serving with Plutarco Elías Calles

|

|

| Succeeded by | Luis N. Morones |

| Secretary of War and Navy | |

| In office 13 March 1916 – 1 May 1917 |

|

| Preceded by | Ignacio L. Pesqueira |

| Succeeded by | Ignacio C. Enríquez |

| Municipal president of Huatabampo | |

| In office 1911–1912 |

|

| Preceded by | José Tiburcio Otero |

| Succeeded by | Benjamín Almada |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Álvaro Obregón Salido

17 February 1880 Siquisiva, Navojoa, Sonora |

| Died | 17 July 1928 (aged 48) San Ángel, Mexico City |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Political party | Laborist Party (PL) |

| Spouse | María Tapia (1888–1971) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Mexican Revolution |

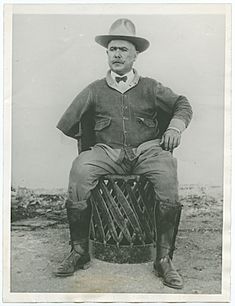

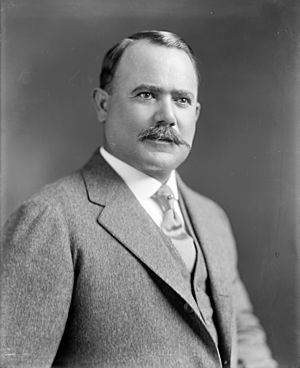

Álvaro Obregón Salido (born February 17, 1880 – died July 17, 1928) was a famous general during the Mexican Revolution. He was a skilled soldier and politician who became the 46th President of Mexico from 1920 to 1924. Sadly, he was assassinated in 1928 just before starting his second term as president. Many people remember him as a great organizer and peacemaker of the Revolution.

Obregón was a successful farmer and a widower raising young children. He joined the Revolution in 1913 after Victoriano Huerta took power from Francisco I. Madero. Obregón supported Venustiano Carranza and his Constitutional Army against Huerta. Even though Obregón wasn't a trained soldier, he quickly became one of the best generals, alongside Pancho Villa. After Huerta was defeated in 1914, Villa and Carranza had a disagreement. Obregón stayed loyal to Carranza and later defeated Villa's army in 1915.

Carranza became the leader of Mexico, and Obregón served as his minister of war. However, Obregón became unhappy with Carranza's conservative ideas. After Carranza was elected president in 1917, Obregón returned to his farm, planning to run for president in 1920. When Carranza tried to choose his own successor, Obregón, along with other generals, started a revolt. Obregón won the presidency with a lot of support.

As president, Obregón brought stability to Mexico after years of fighting. He made big changes in education, supported Mexican art (like murals), and introduced some land and labor reforms. He also signed the Bucareli Treaty in 1923, which helped Mexico get diplomatic recognition from the United States. In 1923, his finance minister, Adolfo de la Huerta, rebelled against him, but Obregón defeated the rebellion with help from the U.S.

In 1924, Obregón's friend, Plutarco Elías Calles, became president. Obregón remained influential and later won the 1928 election. But before he could start his second term, he was assassinated. This event led to Calles creating a new political party, which would rule Mexico for many years.

Contents

Early Life and Farming (1880–1911)

Álvaro Obregón was born in Siquisiva, Sonora, in 1880. He was the youngest of eighteen children. His family had lost their land before he was born, so he grew up in difficult conditions. His mother and older sisters raised him after his father died. Obregón's mother's family was well-known locally, and he used these connections to help himself.

Sonora, Obregón's home state, was far from Mexico City but had strong ties to the U.S. Its economy relied on exporting crops like chickpeas. Obregón became a successful chickpea farmer, which helped him make a good living.

As a child, Obregón worked on the family farm and learned the language of the local Mayo people. Being bilingual helped him later in his military and political career, allowing him to connect with both Mayo and Yaqui people. He went to a school run by his brother and had a practical, inventive mind. He worked various jobs, including as a lathe operator in a sugar mill, which influenced his views on workers' rights.

In 1903, he married Refugio Urrea. After her death in 1907, he was left with two young children, who were raised by his sisters. By 1906, he bought his own farm and grew chickpeas. In 1909, Obregón invented a chickpea harvester and started a company to build them. He also pushed for railway extensions and irrigation projects to help farmers. In 1911, he entered politics and was elected municipal president of Huatabampo.

Military Career and Rise to Power (1911–1915)

Early Military Actions (1911–1913)

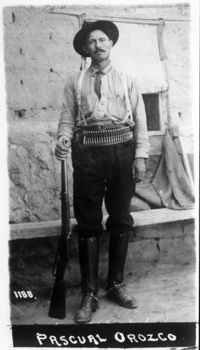

Obregón wasn't involved in the early stages of the Mexican Revolution against Porfirio Díaz. He joined the fight in March 1912, when Pascual Orozco rebelled against President Francisco I. Madero. Obregón volunteered for the local Maderista forces in Sonora.

Within weeks, Obregón showed great military skill. He won battles by using clever tactics like traps and surprise attacks. He was quickly promoted to colonel but resigned in December 1912 after Orozco's rebellion was defeated.

However, in February 1913, President Madero was overthrown and assassinated by Victoriano Huerta. Obregón immediately offered his help to the government of Sonora, which refused to recognize Huerta. In March 1913, Obregón became the chief of Sonora's War Department. He quickly drove federal troops out of several cities and captured the port of Guaymas. His victories earned him respect from many revolutionaries.

Fighting Against Huerta (1913–1914)

Sonora joined forces with Venustiano Carranza of Coahuila, who became the "first chief" of the new Constitutional Army. In September 1913, Carranza made Obregón the commander of the Constitutional Army in the Northwest.

In November 1913, Obregón's forces captured Culiacán, giving the Constitutional Army control of northwestern Mexico. Obregón and other Sonorans were wary of Carranza's Secretary of War, Felipe Ángeles, whom they saw as linked to the old regime. Carranza moved Ángeles to a lower position because of the Sonorans' influence.

Obregón began his march south in April 1914. Unlike Pancho Villa, who preferred wild cavalry charges, Obregón was more careful and strategic. Carranza urged Obregón to move faster to reach Mexico City before Villa. Obregón's troops won a decisive battle in Jalisco in early July, leaving 8,000 federal soldiers dead. Obregón was promoted to major general.

On August 11, Obregón signed the treaties that ended Huerta's rule. On August 16, 1914, Obregón and 18,000 of his troops marched triumphantly into Mexico City, followed by Carranza.

In Mexico City, Obregón took action against those he believed supported Huerta. He fined the Mexican Catholic Church 500,000 pesos and imposed special taxes on the wealthy. He even made some foreign businessmen sweep the streets.

Obregón's Efforts to Unite Revolutionaries (1914)

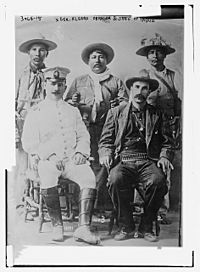

Tensions grew between the conservative Carranza and the more radical Pancho Villa. Obregón tried to mediate between them to keep the revolutionary group together. Villa wanted to cooperate with Obregón against Carranza, but Obregón wasn't ready to break with Carranza yet. He made two risky trips to meet Villa in Chihuahua to try and find a solution.

During their meetings, Obregón and Villa agreed that Carranza should become interim president and restore constitutional government. They also wanted new laws to help the poor and immediate land reform for revolutionary soldiers. Obregón presented these ideas to Carranza, but Carranza rejected them, leading to a formal split with Villa.

The Convention of Aguascalientes (1914)

Despite the split, revolutionary leaders met at the Convention of Aguascalientes in October 1914 to decide Mexico's future. Obregón attended as a general. The convention quickly divided into two groups: Carrancistas, who wanted to restore the old constitution, and Villistas, who, supported by Emiliano Zapata, wanted more social reforms.

For a month and a half, Obregón tried to stay neutral and find a compromise to avoid civil war. When it became clear that the Villistas and Zapatistas were winning at the convention, Carranza refused to accept their decisions. Obregón then sided with Carranza and left the convention, convincing some others to join him. Carranza then announced his own reform program.

War Against the Conventionists (1915)

Obregón again recruited loyal troops by promising them land. In February 1915, the Constitutionalist Army made an agreement with the Casa del Obrero Mundial (House of the World Worker), a labor union. This led to the formation of six "Red Battalions" of workers who fought alongside the Constitutionalists against Villa and Zapata. This agreement also gave Carranza's side more support from urban workers.

Obregón's forces easily defeated Zapata's troops in Puebla. However, Villa's forces still controlled large parts of the country. The armies of Obregón and Villa clashed in four major battles, known as the Battle of Celaya, which were the largest military confrontations in Latin American history at that time.

The main battle took place in Celaya, Guanajuato, between April 13 and 15, when Villa attacked but was pushed back. The most important battle was at Trinidad and Santa Ana del Conde, from April 29 to June 5, where Villa was decisively defeated by Obregón. During this fight, Obregón lost his right arm.

Obregón was known for understanding that modern weapons like field artillery and machine guns gave an advantage to defending forces. While generals in World War I were still using costly mass charges, Obregón used these new tactics effectively in his defense of Celaya.

Obregón's Arm

During the battles with Villa, Obregón's right arm was blown off. The injury was severe, and he even tried to end his own suffering, but his pistol had no bullets. He later told a humorous story about helping search for his missing arm. He said a comrade held up a gold coin, and "everyone saw a miracle: the arm came forth from who knows where, and come skipping up to where the gold azteca [coin] was elevated; it reached up and grasped it in its fingers—lovingly."

His arm was later preserved and displayed in a monument to Obregón in Mexico City. Obregón always wore clothes that showed his missing arm, a visible sign of his sacrifice for Mexico.

Political Career and Presidency (1915–1924)

Carranza's Minister of War (1915–1916)

In May 1915, Carranza declared himself the head of a "Preconstitutional Regime." Obregón, who had chosen to be loyal to Carranza, was appointed Minister of War in his new government. Although their relationship was often tense, Obregón used this position to build his own support among workers, farmers, and politicians. As Minister of War, he worked to modernize the Mexican military, establishing a staff college and a school for military medicine. He also created the Department of Aviation and a pilot training school.

Breaking with Carranza (1917–1920)

In September 1916, Carranza called for a Constitutional Convention to create a new constitution. While Carranza wanted to keep the old 1857 Constitution of Mexico with minor changes, many progressive delegates wanted to include land reform and labor rights. Obregón, though not a delegate, supported the progressives. He met with radical leaders and backed their key demands, especially land reform (Article 27) and strict anti-clerical articles (Articles 3 and 130), which Carranza opposed.

The new Constitution of 1917 was quickly written and approved. Shortly after swearing his loyalty to it, Obregón resigned as Minister of War and returned to his farm in Sonora. He became very successful in farming and remained very popular throughout Mexico as the Revolution's victorious general.

By early 1919, Obregón decided to run for president in the 1920 election. Carranza announced he wouldn't run but refused to support Obregón. Instead, he backed a diplomat named Ignacio Bonillas, a civilian he thought he could control. Obregón announced his candidacy in June 1919, running for the Partido Liberal Constitucionalista (PLC), a party that united most revolutionary generals.

Carranza tried to stop Obregón's campaign. He had the Senate remove Obregón's military rank, but this only made Obregón more popular. Carranza then tried to frame Obregón for planning an uprising, forcing Obregón to flee.

On April 20, 1920, Obregón accused Carranza of using public money to support Bonillas. He declared his loyalty to the governor of Sonora, Adolfo de la Huerta, who was in rebellion against Carranza. On April 23, the Sonorans issued the Plan of Agua Prieta, which started a military revolt. Obregón's forces, joined by other generals and Zapatistas, captured Mexico City on May 10, 1920. Carranza was killed on May 20 while fleeing.

For six months, Adolfo de la Huerta served as provisional president until elections could be held. Obregón won the election, and de la Huerta stepped down, becoming Secretary of the Treasury in Obregón's new government.

President of Mexico (1920–1924)

Obregón's presidency marked the end of the major violence of the Mexican Revolution. He pursued policies that aimed to rebuild the country.

Educational and Cultural Changes

Obregón appointed José Vasconcelos as his Secretary of Public Education. Vasconcelos launched a huge effort to build new schools and libraries across Mexico. About 1,000 rural schools and 2,000 public libraries were built.

Vasconcelos also promoted the Mexican muralism art movement. Artists like Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco were invited to paint murals on public buildings, showing the spirit of the Revolution and Mexico's history.

Obregón also organized big celebrations in 1921 for the 100th anniversary of Mexico's independence from Spain. This was a way for his government to shape how people remembered independence and the Revolution, emphasizing new opportunities for Mexicans after a decade of conflict.

Labor Relations

Obregón kept his promise to Luis Napoleón Morones and the Regional Confederation of Mexican Workers (CROM). He created a Department of Labor and appointed a labor-friendly Minister of Industry and Commerce.

Morones and CROM became very powerful during Obregón's presidency. While CROM's right to strike was recognized, strikes by other unions were often broken up by the police or army. Many workers still didn't get Sundays off with pay or an eight-hour workday, as promised by the constitution.

Land Reform Efforts

Land reform was more widespread under Obregón than under Carranza. He enforced the constitutional rules for land redistribution, giving out 921,627 hectares of land during his term. However, Obregón himself was a successful commercial farmer and didn't fully believe that radical land reform was good for the economy.

Relations with the Catholic Church

Many Catholic leaders and members were critical of the 1917 constitution, especially articles that restricted religious education and the role of priests in public life.

Although Obregón was cautious about the Catholic Church, he was less strict than his successor, Plutarco Elías Calles. Calles's policies later led to the Cristero War. Obregón even sent congratulations to Pope Pius XI upon his election in 1922.

However, some clashes still occurred. Some bishops spoke out against land reform and labor unions. In 1923, a serious incident happened when Ernesto Filippi, the Pope's representative in Mexico, held an outdoor religious service, which was illegal. The government expelled Filippi from Mexico.

Mexico-U.S. Relations

One of Obregón's main goals as president was to get United States diplomatic recognition for his government. He negotiated the Bucareli Treaty in August 1923, which made some concessions to the U.S. to gain recognition. The Mexican Supreme Court also ruled that Article 27 of the constitution, which dealt with oil rights, did not apply to foreign oil companies retroactively.

At the Bucareli Conference, Obregón agreed that Mexico would not take over foreign oil companies. In return, the U.S. recognized his government. Some Mexicans, including Adolfo de la Huerta, criticized Obregón for these concessions.

De la Huerta Rebellion (1923–1924)

In 1923, Obregón supported Plutarco Elías Calles to be the next president. His finance minister, Adolfo de la Huerta, who had been interim president in 1920, rebelled against Obregón and Calles. De la Huerta believed Obregón was trying to choose his own successor, like Porfirio Díaz had done.

More than half of the army joined De la Huerta's rebellion. Obregón's forces crushed the rebels in a decisive battle in Jalisco. The U.S. diplomatic recognition and military aid, including 17 planes that bombed rebels, were very important in Obregón's victory. After defeating the rebellion, Obregón had many of his former comrades executed. De la Huerta went into exile. Calles was then elected president, and Obregón left office.

Later Years and Assassination (1924–1928)

After Calles became president, Obregón returned to Sonora to farm. He started an "agricultural revolution" in the Yaqui Valley, introducing modern irrigation. He expanded his businesses to include a rice mill, a seafood packing plant, a soap factory, and more.

Obregón stayed in close contact with President Calles. This led to fears that Obregón wanted to return to power, like Porfirio Díaz, and that Calles was just a puppet. These fears grew when the Mexican Congress changed the law in October 1926, allowing Obregón to run for president again in 1928.

Obregón briefly returned to the battlefield from October 1926 to April 1927 to put down a rebellion by the Yaqui people. This was ironic because Obregón had once commanded Yaqui troops and promised them land. The Yaqui rebellion was a demand for land reform. Obregón likely participated to show his loyalty to Calles and protect his business interests in the Yaqui Valley.

Re-election and Assassination

Obregón officially began his presidential campaign in May 1927. Many people and the CROM union were against his re-election, but he still had the support of most of the army. Two of Obregón's old allies, General Arnulfo R. Gómez and General Francisco Serrano, opposed his re-election. Serrano launched a rebellion and was assassinated. Gómez also called for an uprising but was soon killed.

Obregón won the 1928 Mexican presidential election. However, months before he could start his second term, he was assassinated. President Calles's harsh treatment of Catholics had led to a rebellion called the Cristero War, which began in 1926. As Calles's ally, Obregón was hated by many Catholics.

On July 17, 1928, Obregón was assassinated at the La Bombilla Café by José de León Toral. Toral was a Roman Catholic who opposed the government's anti-Catholic policies. Toral was later convicted and executed. A nun, María Concepción Acevedo de la Llata, was also involved in the case.

Honors

Álvaro Obregón received Japan's Order of the Chrysanthemum in a special ceremony in Mexico City on November 26, 1924. This honor was given to him by Baron Shigetsuma Furuya, Japan's Special Ambassador to Mexico.

Legacy and Recognition

Álvaro Obregón was a brilliant military leader during the Revolution, famously defeating Pancho Villa at the Battle of Celaya. He went on to become President of Mexico. However, he is not as widely known as heroes like Villa or Emiliano Zapata.

As president, he successfully gained recognition from the United States in 1923 and resolved disputes over oil through the Bucareli Treaty. He also gave full support to his Secretary of Public Education, José Vasconcelos, who greatly expanded access to education and promoted the art of the Mexican muralists. Obregón had the Constitution of 1917 changed so he could run for president again, which many people felt went against the revolutionary principle of "no re-election."

His assassination in 1928, before he could start his second term, caused a major political crisis in Mexico. This crisis was solved by his friend, former President Plutarco Elías Calles, who created the National Revolutionary Party. This party would later be renamed the Institutional Revolutionary Party and would hold the presidency of Mexico until 2000.

A large monument to Álvaro Obregón stands in the Parque de la Bombilla in southern Mexico City. It is Mexico's largest monument to a single revolutionary and is located where he was assassinated. Obregón's body is buried in Huatabampo, Sonora, not in the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City, where other revolutionaries are entombed. In Sonora, there is an equestrian statue of Obregón, showing him as a strong soldier with two arms.

The second largest city in Sonora, Ciudad Obregón, is named after him. Obregón's son, Álvaro Obregón Tapia, later served as governor of Sonora. The Álvaro Obregón Dam, built near Ciudad Obregón, also became operational during his son's time as governor.

A small cactus native to Mexico, Obregonia denegrii, is named in Obregón's honor.

See Also

In Spanish: Álvaro Obregón para niños

In Spanish: Álvaro Obregón para niños