Sonora in the Mexican Revolution facts for kids

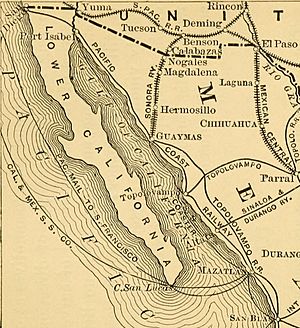

Sonora was a very important area during the Mexican Revolution. Its main leaders were known as the Sonoran Dynasty or the Sonoran Triumvirate. These leaders collectively ruled Mexico for fifteen years, from 1920 to 1935. The state of Sonora, located in northwestern Mexico, was different from other Mexican states. It was far from central Mexico and had strong connections with the United States. Sonora also had large farms that grew crops for export and unique groups of native people. Because many people from Sonora joined the Revolution, its leaders had different ideas compared to those from central Mexico.

Four people from Sonora became Presidents of Mexico: Adolfo de la Huerta, Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Abelardo L. Rodríguez. Seven other key figures of the Revolution also came from Sonora or nearby states. These included José María Maytorena and Benjamín G. Hill, who were middle class. Others were Manuel Diéguez, Salvador Alvarado, Juan G. Cabral, Francisco R. Serrano, and Arnulfo R. Gómez.

Even though he wasn't officially part of the Sonoran Dynasty, General Lázaro Cárdenas (who was born in Michoacán and later became president) was close to Plutarco Elías Calles. However, President Cárdenas later sent Calles into exile in 1936. Recently, historians have started to focus more on Sonora's role in the Mexican Revolution. Before, they mostly studied popular leaders like Pancho Villa from Chihuahua and Emiliano Zapata from Morelos. The Sonoran leaders wanted to improve life for poor Mexicans, make the government stronger, and reduce the influence of the Catholic Church. Like the "Científicos" (a group of advisors to former President Porfirio Díaz), the Sonorans believed in progress, public education (to balance the Church's influence), and using reason to solve problems.

Sonora's Unique Features

Sonora was home to several native groups who played a big part in the state's history. The Yaqui and Mayo lived in rich valleys along the Yaqui and Mayo rivers. These lands were often wanted by people who were not native. The Yaqui people, especially, fought hard to protect their lands. Under their leader Cajeme, they held their territory against outsiders for over ten years. They had a long history of resisting people who tried to take their land, going back to the time when Mexico was a Spanish colony and continuing after Mexico became independent.

Even after Cajeme and his followers were defeated, the Yaqui people continued to resist outsiders in different ways. In the late 1800s, Yaqui and Mayo workers also found jobs in farming and mining. The government of President Díaz tried to stop the Yaqui resistance but failed. So, they forced many Yaqui people to move far away to Yucatan. There, they were made to work on large farms that grew sisal, a plant used to make rope, which was then sent to the U.S. An American journalist named John Kenneth Turner wrote about this forced relocation in his book Barbarous Mexico.

New People Coming to Sonora

Many immigrants from the U.S. came to Sonora in the late 1800s, including Mormons. The U.S. government was not friendly to Mormons because of their practice of polygamy (having more than one spouse). Mormons first moved to the western U.S., settling in Utah before it became a state and polygamy was banned. After the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865), the U.S. government started to punish Mormons for polygamy.

After 1885, some Mormons from Utah, Idaho, and Colorado saw northern Mexico as a place to start a new life. This was because the Mexican central government and the Catholic Church had less power there. While many Mormons settled in the neighboring state of Chihuahua, some also settled in eastern Sonora, in places like Colonia Morelos and Colonia Oaxaca along the Rio Bavispe. Some Sonorans were not happy about this. However, a Mormon settler in Sinaloa said that the Yaqui people, who were usually suspicious, welcomed them.

Chinese immigrants also came to northern Mexico, including Sonora, especially after the U.S. passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This law stopped Chinese people from entering the U.S. Many Chinese first arrived at the port of Guaymas. They often came as single men looking for work, but many later started their own small businesses like stores, laundries, and restaurants. As more Chinese people arrived, they became a visible minority and faced discrimination.

In 1890, Sonora officially started counting foreign residents, and there were only 229 Chinese people. But by 1910, there were nearly 4,500, which was about one-third of all Chinese people in Mexico. They worked with other groups in Sonora, including local Mexican landowners and U.S. investors. Their businesses were usually small and only employed other Chinese people. When the copper mining town of Cananea grew, many Chinese people settled there, creating their largest community in Sonora. They sold supplies to the many mine workers who came to the town. Some Chinese also started small farms to grow vegetables for local markets. These farms did not compete with the larger farms that grew grains. Some large estates even leased land to them that wasn't good for growing grains. As Chinese people became more involved in Sonora's economy, many Mexicans saw them as a threat. The Díaz government actually encouraged Chinese immigration to help develop the economy. However, the Liberal Party of Mexico's plan in 1906 included rules against Chinese immigration.

Sonorans in History

Even though the Sonorans played a key role in the Constitutionalist side winning the Revolution, they haven't been celebrated in the same way as Villa or Emiliano Zapata. There hasn't been a major study focusing on all the Sonorans together, though there are books about Obregón and Calles in English. Historians have often focused more on Lázaro Cárdenas's presidency (1934-1940), which has overshadowed the achievements of Obregón and Calles.

Mexican historian Héctor Aguilar Camín described the Sonorans as "tough outsiders who took over a nation where they remained strangers." He said they were "anti-church and frontier people who overcame an old Mexico that was Catholic, native, and mixed-race." Calles's remains are now in the Monument to the Revolution in central Mexico City, but Obregón's are not. A huge monument to Obregón was built in the San Angel neighborhood of Mexico City, where he was assassinated. For many years, it held the preserved arm he lost in a battle against Villa. His body was buried in Huatabampo.

De la Huerta started a rebellion in 1923 when Obregón chose Calles to be his successor instead of him. For a long time, De la Huerta was seen as a less important figure among the Sonorans. However, recent research has started to show his contributions more clearly. Obregón's cousin, Benjamín Hill, has also not been fully recognized for his work. But he was a "crucial general in the Sonoran area" and helped organize the Liberal Constitutionalist Party for the 1920 elections. He was called "Obregón's lost right arm," referring to the arm his cousin lost in the 1915 battle where Villa was defeated. Hill became the Secretary of War in Obregón's government but died mysteriously soon after. Calles saw Hill as a rival, and people immediately blamed Calles for Hill's death.

Images for kids

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |