Venustiano Carranza facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Venustiano Carranza

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 44th President of Mexico | |

| In office 1 May 1917 – 21 May 1920 |

|

| Preceded by | Francisco S. Carvajal |

| Succeeded by | Adolfo de la Huerta |

| Head of the Executive Power First Chief of the Constitutionalist Army |

|

| In office 14 August 1914 – 30 April 1917 |

|

| Governor of Coahuila | |

| In office 22 November 1911 – 7 March 1913 |

|

| Preceded by | Reginaldo Cepeda |

| Succeeded by | Manuel M. Blázquez |

| In office 29 May 1911 – 1 August 1911 |

|

| Preceded by | Jesús de Valle |

| Succeeded by | Reginaldo Cepeda |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Venustiano Carranza de la Garza

29 December 1859 Cuatro Ciénegas, Coahuila, Mexico |

| Died | 21 May 1920 (aged 60) Tlaxcalantongo, Puebla, Mexico |

| Political party | Democratic Party of Mexico & Liberal Constitutionalist Party |

| Spouses | Virginia Salinas Ernestina Hernández |

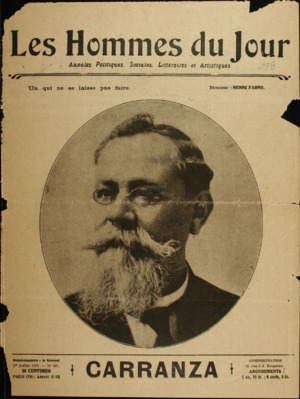

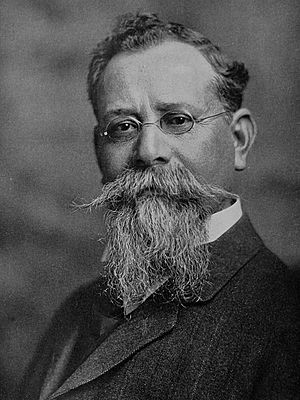

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza (born December 29, 1859 – died May 21, 1920) was a wealthy landowner and important politician in Mexico. He was the Governor of Coahuila state when Mexico's elected president, Francisco I. Madero, was overthrown in a military takeover in February 1913.

Carranza became known as the Primer Jefe (which means "First Chief") of the Constitutionalist group during the Mexican Revolution. He was a very smart politician. He had supported Madero's challenge to the long-time leader Porfirio Díaz in the 1910 elections. After Madero became president, Carranza was made governor of Coahuila.

When Madero was killed in 1913, Carranza created the Plan of Guadalupe. This plan aimed to remove the new leader, General Victoriano Huerta, who had taken power illegally. Because Carranza was a sitting governor, he had legal power and became the leader of the northern groups against Huerta. The Constitutionalists won, and Huerta was forced out in July 1914.

Carranza did not immediately become president. Instead, a civil war broke out among the winning groups. Two of his best generals, Álvaro Obregón and Pancho Villa, disagreed with him. Obregón stayed loyal to Carranza, but Villa joined forces with peasant leader Emiliano Zapata. Obregón's army defeated Villa's forces.

With his position strong, Carranza called for a meeting in 1916 to create a new Mexican Constitution. This new constitution, finished in 1917, gave the government power to make big changes, like land reform and workers' rights. Carranza was then elected president and served from 1917 to 1920. However, he did not make many of the big changes promised in the new constitution. He also tried to get rid of his political enemies, including having Zapata killed in 1919.

In 1920, Carranza tried to choose his own successor for president, which angered powerful generals like Obregón. These generals rebelled against him. Carranza fled Mexico City and was killed by rebels. Even though he played a huge role in the Revolution, his contributions were not fully recognized in Mexico for a long time because he was overthrown. Later, his place in Mexican history became more secure.

Contents

- Early Life and Education (1859–1887)

- Political Career Begins (1887–1909)

- Supporting Francisco Madero (1909–1911)

- Governor of Coahuila (1911–1913)

- Primer Jefe of the Constitutionalist Army (1913–1914)

- Break with Pancho Villa

- Convention of Aguascalientes (October 1914)

- Carranza's Victory (1915)

- Leading the Pre-constitutional Government (1915–1917)

- Constitutional Convention of Querétaro (1916–1917)

- Constitutional President of Mexico (1917–1920)

- Foreign Policy

- Election of 1920 and Death

- After His Death

- In Historical Memory

- See also

Early Life and Education (1859–1887)

Venustiano Carranza was born in 1859 in Cuatro Ciénegas, a town in the state of Coahuila. His family was wealthy and owned many cattle ranches. His father, Jesús Carranza Neira, was a rancher who fought on the Liberal side during the Reform War (1857–1861).

During the French intervention in Mexico (1861–1867), when France tried to make Mexico a monarchy, Carranza's father supported President Benito Juárez. He became a colonel and was an important contact for Juárez in Coahuila. Carranza's father even lent money to Juárez's government when it was in exile. After the French left, Juárez rewarded Carranza's father with land, which helped the family become even wealthier.

Because his family was rich, Venustiano, who was the 11th of 15 children, went to excellent schools. He studied in Saltillo and later in Mexico City. In 1874, he attended the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (National Preparatory School) in Mexico City, hoping to become a doctor.

In 1876, while Carranza was still in school, Porfirio Díaz started a rebellion. Díaz's slogan was "No Re-election," meaning a president should not be re-elected. Díaz's troops won, and he took power, staying in charge for many years until 1911. After finishing his schooling, Carranza began his political career in Coahuila during Díaz's time. In 1882, he married Virginia Salinas, and they had two daughters.

Political Career Begins (1887–1909)

As an educated person from a well-known family in Coahuila, Carranza had the right background to enter politics. In 1887, at age 28, he became the mayor (municipal president) of Cuatro Ciénegas. There, he started making changes to improve education. Carranza remained a Liberal, admiring Benito Juárez. He became unhappy with how Díaz's rule became more and more strict.

In 1893, about 300 ranchers in Coahuila, including Venustiano and his brother Emilio, protested against the re-election of Porfirio Díaz's supporter, José María Garza Galán, as Governor of Coahuila. Díaz sent his trusted man, Bernardo Reyes, to handle the situation. Carranza and his brother met with Reyes to explain why they opposed Garza Galán. Reyes agreed with them and told Díaz to remove his support for Garza Galán. Díaz listened, and a new governor was appointed who was acceptable to Reyes and the Carranza family. This event showed Díaz how much power the Carranza family had in the state.

These events helped Carranza make important connections, including with Bernardo Reyes. After serving a second term as mayor (1894–1898), Carranza was elected to the national legislature with Reyes's help. In 1904, Reyes's friend, Miguel Cárdenas, who was Governor of Coahuila, suggested to Díaz that Carranza would be a good senator. Carranza became a senator later that year.

As a senator, Carranza supported laws that would limit foreign investors in Mexico. As the 1910 presidential election approached, Bernardo Reyes considered running for president. Díaz had said he would not run again but then changed his mind. Because Reyes was a strong candidate, Díaz did not support Carranza for governor of Coahuila. Díaz sent Reyes out of the country. Carranza then joined forces with Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy landowner who was challenging Díaz.

Supporting Francisco Madero (1909–1911)

Carranza was very interested in Francisco Madero's movement against re-election in 1910. After Madero fled to the U.S. and Díaz was re-elected, Carranza went to Mexico City to join Madero. Madero named Carranza the temporary Governor of Coahuila.

Madero's Plan of San Luis Potosí called for a revolution to begin on November 20, 1910. Madero made Carranza the commander-in-chief of the Revolution in Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas. However, Carranza struggled to organize an uprising in these states. Some of Madero's supporters even thought Carranza might still be loyal to Bernardo Reyes.

After revolutionary leaders like Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa won a big victory against the Federal Army at Ciudad Juárez, Carranza traveled there. Madero named Carranza his Minister of War on May 3, 1911, even though Carranza hadn't contributed much to the rebellion.

The revolutionaries disagreed on what to do with Porfirio Díaz and his vice president. Madero wanted them to resign, with a temporary president taking over until new elections. Carranza disagreed. He argued that letting Díaz and his vice president simply resign would make their illegal rule seem legitimate. He believed a temporary government would just continue the dictatorship and hurt the Revolution. Madero's idea won, but Carranza's concerns proved to be right. Madero's victory did give Carranza power in Coahuila during Madero's presidency (November 1911-February 1913).

Governor of Coahuila (1911–1913)

Carranza returned to Coahuila to serve as governor. He easily won the elections held in August 1911. Because Carranza had supported Madero against Díaz, Madero gave him a lot of freedom to govern Coahuila.

As governor, Carranza started many reforms. He changed the justice system, legal codes, and tax laws. He introduced rules to make workplaces safer, prevent mining accidents, and stop unfair practices at company stores. He also worked to break up business monopolies and control gambling. Carranza invested a lot in education, believing it was key to society's progress.

An important step Carranza took was creating an independent state militia. This militia was controlled by the governor and could put down rebellions. It also gave the state more independence from the central government.

However, the relationship between Carranza and Madero began to worsen. Carranza had only joined Madero after Díaz sent his mentor, Reyes, out of the country. Madero was suspicious of Carranza's loyalty. Carranza had already disagreed with Madero's decision to have a temporary presidency after the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez. Once Madero became president, Carranza criticized him for being weak. Madero, in turn, accused Carranza of being mean and bossy.

Carranza believed there would soon be a rebellion against Madero. So, he formed alliances with other Liberal governors, including Pablo González Garza of San Luis Potosí and Abraham González of Chihuahua. Carranza was not surprised when, in February 1913, Reyes, Victoriano Huerta, and Félix Díaz (Porfirio Díaz's nephew) overthrew Madero. This event, known as La decena trágica (the Ten Tragic Days), involved fighting in the capital. Reyes was killed during this time. With his mentor gone, Carranza was unsure what to do next. There is some evidence that Carranza tried to negotiate with Huerta right after the takeover, but they didn't reach an agreement.

Primer Jefe of the Constitutionalist Army (1913–1914)

Carranza declared himself in rebellion against Huerta's new government. Carranza's stand against Huerta was a strong move. He had political power as a state governor, a good record of reforms, and support in his state. He was also a skilled politician who formed alliances to create a large northern group against Huerta. This group became known as the Constitutionalists, because they aimed to defend the liberal Constitution of 1857. Carranza was both the official and actual leader of this movement.

In late February 1913, Carranza asked the Coahuila legislature to formally declare itself in rebellion against Huerta's government. He had built a state militia, funded by new taxes on businesses. However, this militia could not stand against Huerta's well-armed Federal Army. Carranza's militia suffered defeats, forcing him to flee to Sonora, a revolutionary stronghold. Before leaving Coahuila, he found a group of young men who had written a plan similar to Madero's. This Plan of Guadalupe rejected Huerta and his government. The plan named Carranza as Primer Jefe ("First Chief") of the Constitutional Army. It also stated that Carranza would become the temporary president of Mexico and then call for new elections.

Carranza's Plan of Guadalupe did not promise many reforms. He believed Madero's mistake was promising too many social changes that he couldn't deliver. Carranza thought a simple call to restore the constitution and remove Huerta would be more effective. He believed this would make reforms possible later. When the Federal Army collapsed in 1914, Carranza updated the Plan of Guadalupe to promise big reforms. This was done to gain support and weaken the appeal of more radical revolutionaries like Villa.

Carranza himself was not a military man. However, the Constitutionalist Army had brilliant military leaders, especially Álvaro Obregón and Pancho Villa. Initially, Carranza divided the country into three main zones for the Revolution: the northeast (under González Garza), the center, and the northwest (under Obregón). The fight against Huerta in March 1913 started slowly. Huerta's troops forced Carranza to flee to Sonora in August 1913.

After a difficult start, the Constitutionalist Army grew much stronger. By March 1914, Carranza learned of Villa's victories and advances by González Garza and Obregón. He felt safe enough to leave Sonora and moved his capital to Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, on the U.S. border.

Many Mexican Protestants and American Protestant missionaries supported Carranza's cause. Mexican ministers and their churches joined the fight against Huerta, mostly following Carranza. Even though Protestants were a small part of Mexico's population, many served as officers in the Constitutionalist Army and in government positions once Carranza took power.

In Sonora, Carranza met revolutionaries from middle and working-class backgrounds. He attracted skilled men who were not trained soldiers, like Álvaro Obregón, Benjamin G. Hill, and Plutarco Elías Calles. He also gained support from Pancho Villa of Chihuahua, who had been important in overthrowing Díaz.

Pancho Villa commanded the Division of the North and recognized Carranza as the commander-in-chief. However, Villa's actions often caused problems for Carranza with other countries. Villa seized property from Spaniards and was involved in the deaths of an Englishman and a U.S. citizen. At one point, Villa arrested the Governor of Chihuahua, forcing Carranza to travel there to order Villa to release him.

Villa also disagreed with Carranza about the U.S. occupation of Veracruz. After a small incident, the United States sent troops to occupy the important port of Veracruz, Veracruz. Carranza, a strong nationalist, threatened war with the U.S. He demanded that U.S. troops leave Mexico. Villa, however, told a U.S. official that he had no problem with the U.S. holding Veracruz. This showed a clear difference in their foreign policy views.

The revolutionary forces led by Carranza and Emiliano Zapata defeated the Federal Army in the summer of 1914. Huerta fled Mexico on July 15, 1914. Carranza demanded that the Federal Army be completely dissolved, learning from Madero's mistake of allowing it to continue. The fight against Huerta officially ended on August 13, 1914. On August 20, 1914, Carranza made a triumphant entry into Mexico City. Carranza, with Obregón's support, was now the strongest leader and set up the new government.

Carranza greatly benefited from U.S. support as Huerta's government fell. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson refused to recognize Huerta's government. In November 1913, Wilson considered allowing arms sales to the Constitutionalists to help them fight Huerta. Carranza wanted U.S. recognition and weapons but did not want to make public promises to the U.S. He sent Luis Cabrera Lobato, a lawyer fluent in English, to Washington D.C. to negotiate. Cabrera was a talented civilian who became Carranza's main advisor and later his Minister of Finance. He helped draft Carranza's land reform law, which was important for gaining peasant support.

The long civil war in Mexico threatened U.S. investments. Revolutionaries often took resources from foreign businesses to fund their fight. Carranza was seen as a serious, skilled, and deeply nationalist politician. His political plan, which didn't promise big social or economic changes at first, seemed like the best way to end the conflict and bring back order. When the U.S. occupied Veracruz, Carranza took a strong public stand against them. When Huerta was forced into exile, the U.S. left their weapons and supplies in Veracruz for the Constitutionalist Army.

Break with Pancho Villa

Tensions between Carranza and Pancho Villa were high throughout 1913-14. Villa often ignored Carranza's orders. Before Huerta's army was defeated, Villa defied Carranza and successfully captured Zacatecas, a key silver-producing city. This was a very bloody battle. Carranza had tried to stop Villa from winning this victory to avoid giving Villa more political power. Carranza even tried to get some of Villa's men to join other generals, but those generals criticized Carranza for being bossy and jealous. Villa's capture of Zacatecas effectively broke Huerta's government.

After Huerta's defeat, the tensions between Villa, Obregón, and Carranza exploded. Villa felt disrespected by Carranza. Obregón tried to keep the revolutionary groups together. Both Villa and Obregón disagreed with Carranza continuing to lead an unofficial government. Carranza did not want to become temporary president because it would stop him from running for president later. Obregón warned Carranza that this would cause a break with Villa, but Carranza took the risk. Obregón eventually decided Villa was dangerous and chose to support Carranza. Carranza didn't fully trust Obregón, but he needed his military support.

Carranza feared Villa would reach Mexico City first, as taking the capital was a powerful symbol. In August, Carranza refused to let Villa enter Mexico City with him and refused to promote Villa. Villa formally broke away from Carranza on September 23, 1914.

Convention of Aguascalientes (October 1914)

After Huerta was removed, the alliance that had fought him began to fall apart. The different Constitutionalist groups met to decide what to do next. Even though Carranza was the primer jefe, many military leaders in different regions were quite independent and not fully loyal to him.

Carranza wanted to control the meeting. He set the date for October 1, 1914, in Mexico City, which his troops controlled. He offered to resign, but the delegates, many of whom he had chosen, refused. He expected them to confirm his leadership. However, the more radical members of Carranza's group agreed to move the meeting to Aguascalientes, a neutral location. This meeting was supposed to include only military leaders, which meant some of Carranza's best generals did not attend.

Before the convention, both Carranza's loyalists and Villa's independent forces were recruiting soldiers. Villa welcomed soldiers from the defeated Federal Army into his ranks. Carranza's forces recruited in Veracruz and gained weapons that Huerta had stored there.

Many at the Aguascalientes convention wanted a middle path between Villa, Zapata, and Carranza. They saw Villa and Zapata as too extreme and Carranza as too traditional. Leaders like Obregón and Eulalio Gutiérrez gained enough support to elect Gutiérrez as temporary president of Mexico for just 20 days. This decision made Carranza lower in rank than Gutiérrez and removed Villa from military command. But Carranza simply ignored these decisions and called his generals back from Aguascalientes.

When it was clear the convention failed, the groups prepared for war. Obregón and the Sonorans stayed with Carranza, likely believing they would have more influence with him than with Villa. Carranza was in a weaker position, controlling less land and having fewer troops than Villa and Zapata. He lost supporters and had to leave the capital for Veracruz state, which became his stronghold. This territory was important because it had oil and Mexico's two main ports. With the start of fighting among the winners, the Revolution entered another major phase.

Carranza's Victory (1915)

The Aguascalientes convention had rejected Carranza, and he rejected its decisions. The convention's government was weak. In theory, the alliance of Zapata and Villa had more soldiers than Carranza's armies. Right after the convention, a Carranza victory seemed unlikely. He controlled little land and had a smaller fighting force. However, Álvaro Obregón's loyalty was key. Also important was Carranza's control of the oil-rich Gulf Coast and the main ports of Veracruz and Tampico.

In November 1914, things started to turn in Carranza's favor when the U.S. agreed to leave the port of Veracruz, leaving behind many weapons. Carranza set up his government in Veracruz, while the Convention forces held Mexico City. In late 1914, Carranza began issuing new reform laws, especially his "Additions to the Plan of Guadalupe." These additions outlined the social and economic goals of his government, which the original plan had not done. The additions included promises to return land to communities and break up large estates. This was important for gaining the support of peasants who wanted land.

In January 1915, Carranza issued an agrarian (land) law, creating communally held village lands called ejidos. He saw these as "reparations for past injustices." While Carranza appealed to peasants, he also quietly promised landowners that their seized estates would be returned. This brought many landowners in the north to support Carranza. Some even formed militias of their workers to fight Villa's forces. Historian Friedrich Katz suggested that peasants joined Carranza because his land law was a national policy, not just for specific regions like Zapata's or Villa's.

Carranza also gained support from the urban working class. Workers were inclined to support him because of his strong stance against the U.S. occupation of Veracruz and his position on foreign-owned businesses. Where Carranza's armies won in cities, he encouraged the formation of labor unions. Carranza negotiated with the Casa del Obrero Mundial, a labor organization, which formed Red Battalions of workers to fight against Villa and Zapata. In return, Carranza promised to pass labor laws favorable to workers. These Red Battalions included artisans and painters like José Clemente Orozco. Urban workers saw their interests as different from peasants. They wanted cheap food, not peasants farming small plots.

The real victory against Villa came with Obregón's defeat of Villa in two major battles at Celaya. Obregón used modern tactics like machine guns and barbed wire against Villa's cavalry charges. Villa's forces suffered heavy losses, while Obregón's had few. These defeats ended Villa's effective fighting power and strengthened Carranza's position as leader. Obregón's victory made him famous, and he became Carranza's Minister of War.

Another important general for Carranza was Pablo González, who fought against Zapata in Morelos. González managed to break up Zapata's armies into smaller guerrilla groups. The United States recognized Carranza as President of Mexico in October 1915. By the end of the year, Villa was on the run.

Leading the Pre-constitutional Government (1915–1917)

After the defeat of Villa's División del Norte in the Battles of Celaya in April 1915, and the Zapatista army, Carranza became the head of what he called a "Pre-constitutional Government." This government would last until the 1917 Constitution was approved and he was elected constitutional president.

Carranza officially took charge of the executive branch on May 1, 1915. Both Villa and Zapata remained threats, even though they no longer had large armies. The Zapatistas continued fighting as guerrillas in Morelos. Villa deliberately provoked the U.S. with a raid on Columbus, New Mexico in 1916. This led to a U.S. Army invasion into Mexico to try and capture him, but they failed.

To counter Villa's appeal to peasants, Carranza issued "Additions to the Plan of Guadalupe" on December 12, 1914. This plan outlined an ambitious reform program, similar to Benito Juárez's Laws of Reform.

Carranza implemented reforms in specific ways:

- Judicial Reform: Carranza made important changes to ensure Mexico had an independent justice system.

- Labor: In February 1915, the Constitutionalist Army signed an agreement with the Casa del Obrero Mundial ("House of the World Worker"), a labor union. This led to the creation of six Red Battalions of workers who fought alongside the Constitutionalist Army against Villa and Zapata.

After Villa and Zapata were defeated, Carranza's relationship with organized labor worsened. He disbanded the Red Battalions in January 1916, as they were no longer needed. He also likely worried about these armed workers turning against his government. The workers' wages were paid in paper money that lost value quickly, and jobs were scarce. The Casa del Obrero Mundial continued to recruit and organized strikes against Carranza's government and businesses, including textile factories and British oil companies. Other workers, like teachers and miners, also went on strike. Workers successfully gained higher wages and better working conditions.

The Casa's demands became more extreme, and as its membership grew, Carranza worried about the survival of capitalism. He used the army against striking workers. In May 1916, the Casa organized a general strike in Mexico City, cutting off electricity. General Benjamin Hill, Obregón's cousin, negotiated with the workers, and the immediate threat was avoided. However, the Casa staged a second general strike in July 1916, which Carranza's forces suppressed instead of negotiating. In August 1916, the Casa del Obrero Mundial was forcibly shut down by the police. An old law from 1862 was brought back, making striking a crime punishable by death. Carranza believed workers were "denying the sacred recognition of the fatherland."

- Land Reform: Although Carranza passed a land law, the situation was complex. Different groups had seized large estates during the fighting. Once Carranza gained power in mid-1915, he took control over these seized properties. This brought money to his government. More importantly, it meant that landowners had to ask Carranza to return their properties, not local revolutionary officials. Politically, this helped Carranza gain loyalty from landowners by returning their lands. Carranza himself was a hacienda owner and sympathized with them. He returned many estates to their former owners, but not to his political enemies.

- Natural Resources and Foreign Companies: During Porfirio Díaz's presidency, foreign mining and oil companies received special deals to develop Mexico's natural resources. On January 7, 1915, Carranza declared his intention to return the wealth of oil and coal to the Mexican people. He faced challenges because a local general, Manuel Peláez, controlled the oil-rich region and protected the oil companies in exchange for money. Carranza raised taxes on mining companies and removed their right to appeal to foreign governments, making them subject to Mexican courts. (The U.S. opposed these policies and delayed them.)

Constitutional Convention of Querétaro (1916–1917)

Carranza called for a Constitutional Convention in September 1916, to be held in Querétaro. He said that the liberal 1857 Constitution of Mexico would be respected but improved.

When the convention met in December 1916, it had 85 conservative and moderate delegates who were close to Carranza. But there were also 132 more radical delegates. These radicals insisted that land reform must be included in the new constitution. They were inspired by Andrés Molina Enríquez's ideas. Although Molina Enríquez was not a delegate, he advised the committee that wrote Article 27 of the constitution. This article stated that private property was created by the Nation, and the Nation had the right to regulate it. It said that communities without enough land could take it from large estates (latifundios and haciendas). Article 27 also declared that only native-born Mexicans could own property rights in Mexico. It said that if the government granted rights to foreigners, these rights were temporary and could not be appealed to foreign governments.

The radicals also went further than Carranza on labor rights. In February 1917, they wrote Article 123 of the Constitution. This article established an eight-hour workday, banned child labor, protected female and young workers, required holidays, provided fair wages, and set up arbitration boards for disputes.

The radicals also made stronger changes to the relationship between the church and the state than Carranza wanted. Articles 3 and 130 were very anti-clerical. The Roman Catholic Church in Mexico was not recognized as a legal group. Priests lost many rights and had to register with the government. Religious education was forbidden, and public religious ceremonies outside of churches were banned. All churches became property of the nation.

In short, even though Carranza was the main supporter of constitutionalism, the 1917 Constitution of Mexico was more radical than he had planned. However, Carranza's supporters did win some important points. The power of the president was increased, and the power of the legislature was reduced. The position of Vice-President was removed. Judges were given lifetime appointments to ensure their independence.

Constitutional President of Mexico (1917–1920)

The new constitution was announced on February 5, 1917. Carranza faced little opposition in his election as president. In May 1917, Carranza became the official President of Mexico.

Carranza intentionally made few big changes while in office. Those who hoped for a new, revolutionary Mexico after the fighting were disappointed. Mexico was in a very difficult state in 1917. The fighting had ruined the economy, destroyed food supplies, and caused widespread disease.

Carranza also faced many armed enemies. Emiliano Zapata continued his rebellion in Morelos. Félix Díaz, Porfirio Díaz's nephew, had returned to Mexico and organized an army. Other groups opposed Carranza in different states. Pancho Villa remained active in Chihuahua, though he no longer had large forces.

After Carranza was elected president, Obregón retired to his ranch. The fighting continued, especially against Zapata. Carranza ordered the assassination of Emiliano Zapata in 1919.

Carranza kept Mexico neutral during World War I. He briefly considered allying with Germany after Germany sent the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917. This telegram invited Mexico to join the war on Germany's side. It promised German help for Mexico to reclaim territory lost to the United States, like Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. Carranza had a general study this possibility but decided that war with the U.S. was not practical. He believed Germany could not guarantee aid due to the British navy's blockade.

Carranza was not enthusiastic about the anti-clerical Articles 3 and 130 of the Mexican Constitution, which he had opposed. He believed that people's customs don't change overnight. He proposed an amendment to change these parts of the constitution, but it was rejected. The anti-clerical articles were not fully enforced until the presidency of Plutarco Elías Calles (1924-1928), which led to a pro-Catholic uprising called the Cristero War.

Corruption was a big problem during Carranza's presidency. A popular saying was that "The Old Man doesn't steal, but he lets them steal." A new verb, carrancear, was even created, meaning "to steal."

Foreign Policy

Carranza kept Mexico neutral during World War I. This was influenced by strong anti-American feelings due to past U.S. interventions in Mexico. For example, the U.S. ambassador had helped overthrow President Madero in 1913. President Woodrow Wilson also ordered the invasion of Veracruz in 1914, which killed many Mexican soldiers and civilians.

Relations between Carranza and Wilson were often tense. However, Carranza managed the difficult situation well. Germany officially recognized his government in early 1917. The United States recognized him on August 31, 1917, partly because of the Zimmermann Telegram. This recognition helped ensure Mexico's continued neutrality in the war.

Carranza allowed German companies to continue operating in Mexico. At the same time, he sold oil to the British. Over 75 percent of the fuel used by the British fleet came from Mexico. Carranza did not accept Germany's military alliance offer. He also prevented another U.S. invasion, which aimed to control the important oil fields. By 1917, Mexico produced over 55 million barrels of crude oil, which was vital for the Allied war effort. Carranza threatened to burn the oil fields if the U.S. invaded.

Election of 1920 and Death

Because Porfirio Díaz's long rule was a major cause of the Revolution, Carranza wisely decided not to run for re-election in 1920. His natural successor was Álvaro Obregón, the general who defeated Pancho Villa. However, Carranza believed Mexico should have a civilian president. So, he supported Ignacio Bonillas, a little-known diplomat.

As government supporters tried to stop Obregón's campaign, Obregón decided Carranza would not leave office peacefully. Obregón and other powerful generals from Sonora, including Plutarco Elías Calles and Adolfo de la Huerta, issued the Plan of Agua Prieta. This plan rejected Carranza's government and restarted the Revolution.

On April 8, 1920, an attempt was made to assassinate Carranza. After it failed, Obregón brought his army to Mexico City and forced Carranza out. Carranza fled towards Veracruz, hoping to regroup. However, he was betrayed and killed on May 21, 1920, while sleeping in Tlaxcalantongo in the mountains. His forces were attacked by General Rodolfo Herrero, a local leader who had supported Carranza's former allies. Some historians believe Carranza was murdered in a planned attack. Other historians suggest Carranza took his own life rather than be captured. The exact truth is still debated.

After His Death

After Carranza's death, Obregón prosecuted Colonel Herrero for the murder, but Herrero was found innocent. Obregón was not in Mexico City when Carranza's body was brought for burial. A newspaper reported that about 30,000 Carranza supporters attended the funeral. Carranza was first buried in a regular section of the Dolores Cemetery. In 1942, his remains were moved to the Monument to the Revolution.

During Obregón's presidency (1920–24), his office contacted Carranza's daughter, Julia. They offered her a pension, saying that "Venustiano Carranza gave eminent services to the Revolution and to the Nation." However, Julia and her brother refused the pension. They bitterly replied that Obregón was responsible for their father's death and no money could make up for it. They signed the letter, "Your loyal enemies, Julia, Emilio, Venustiano, and Jesús Carranza."

In Historical Memory

In 1920, José Vasconcelos, who became Obregón's Minister of Education, wrote that Carranza's death brought a "wave of peace." He felt that Carranza's disappearance made former enemies seek peace and feel like brothers again.

During Obregón's government, an official history of the Revolution was created, focusing on the idea of the "Revolutionary Family." At first, Carranza was seen as someone who went against the Revolution, grouped with Porfirio Díaz and Victoriano Huerta. He wasn't even given credit for the 1917 Constitution. Obregón's supporters tried to improve Madero's reputation, which Carranza had criticized.

Carranza's supporters tried to defend his reputation in the 1920s. However, the official history favored the reputations of Emiliano Zapata (whom Carranza had killed) and Pancho Villa (whom Obregón had killed). During his presidency, Carranza had tried to shape history in his favor. He emphasized the date of his 1913 Plan of Guadalupe over Madero's 1910 Plan of San Luis Potosí. But under Obregón, November 20, the date Madero called for rebellion, became an official holiday.

The tall, gray-bearded Carranza was the "old man" of the Revolution. As a governor, he was a smart and practical politician. His early opposition to Huerta helped him build a strong group against the illegal leader. He was known for being distant and not very charming, unlike Obregón and Villa. His lack of charisma affected his place in popular memory. There were no popular corridos (songs about events and people) about Carranza, unlike for Zapata and Villa, which kept their memories alive. Instead, Carranza used official offices to create pro-Constitutionalist propaganda and gain national support. He also supported newspapers that favored his cause.

Carranza thought Madero was a young and naive dreamer. Even though he supported Madero against Díaz, he criticized Madero for being too forgiving towards Díaz and the old system. Madero chose to follow strict legal rules during the presidential change. He kept the old Federal Army and disbanded the revolutionary forces that brought him to power. Carranza learned from this mistake. When his Constitutionalist Army defeated the Federal Army in 1914, he disbanded the Federal Army, keeping the revolutionary armies in place.

Carranza was the first major figure to oppose Huerta and declared that those who opposed him would be executed. Events showed that Carranza was right about Madero's errors. Carranza kept a broad northern alliance against Huerta together in 1913-14. But after Huerta was gone, big problems appeared. Carranza had enough support, especially from Obregón, to gain power. Once in power, Carranza and his followers presented themselves as continuing Madero's legacy, but with implied criticisms. Carranza saw himself as starting the true revolution in Mexico, not just a change in president, but a social revolution. Villa broke with Carranza in 1914, seeing him as a traitor to revolutionary ideals because he didn't move on reforms. Zapata never joined Carranza's northern alliance. In 1916, Zapata called Carranza a liar, saying he "pretends to be the genuine representative of the Great Masses of the People, and as we have seen, he not only tramples on each and every revolutionary principle, but harms... the most precious rights and the most respectable liberties of man and society."

Carranza is remembered as one of the "Big Four" of the Revolution, along with Zapata, Villa, and Obregón. Although he was more powerful than any of them for most of 1915-1920, he is probably the least remembered in popular culture today. There isn't a major biography of Carranza like there is for the other top revolutionaries. Even so, Carranza prevented a permanent invasion of Mexico by the U.S., which wanted to control the oil fields. As historian Lester Langley wrote: "Carranza may not have fulfilled the social goals of the revolution, but he kept the gringos out of Mexico City."

Carranza led the broad Constitutionalist movement against Huerta, uniting political and armed groups in northern Mexico to restore constitutional law. Brilliant military leaders served Carranza, including Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Lázaro Cárdenas, all of whom later became presidents of Mexico. Carranza pursued a strong nationalist policy, standing up to huge economic and political pressure from the U.S. His call for a new constitution was achieved, with key revolutionary goals like land reform, workers' rights, and control over foreign interests becoming law.

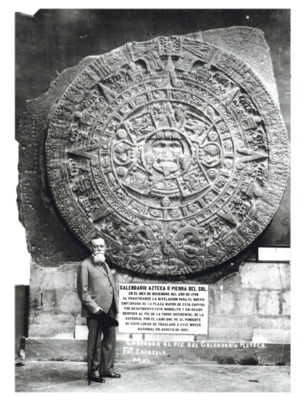

By 1942, the Monument to the Revolution was built. It was made from the unfinished structure of the Mexican legislature building that was abandoned when the revolution against Díaz began. By then, all the major figures of the Revolution were either dead or no longer in power. General Lázaro Cárdenas, who was president from 1934-40, chose his successor. The ruling party was later renamed the Institutional Revolutionary Party. This shift meant the Monument to the Revolution could house the remains of members of the "Revolutionary Family." Carranza's ashes were moved from the Dolores Cemetery with a big ceremony and parade through Mexico City. They were placed in one of the monument's four pillars. This happened on the 25th anniversary of the 1917 Constitution. Carranza and other revolutionaries have their death anniversaries officially remembered.

See also

In Spanish: Venustiano Carranza para niños

In Spanish: Venustiano Carranza para niños