Land reform in Mexico facts for kids

Before the Mexican Revolution in 1910, most land in Mexico was owned by a few rich Mexicans and foreigners. Small farmers and indigenous communities had very little good land. During the time when Spain ruled Mexico (the colonial era), the Spanish king tried to protect the lands of indigenous communities. These communities mostly grew food for themselves (called subsistence farming).

In the 1800s, rich Mexicans created huge farms called haciendas across the country. Many small farmers, often of mixed race (mestizos), also worked in the economy. After Mexico became independent, some Mexican leaders wanted to modernize the country. They believed that lands owned by groups, like the Catholic Church and indigenous communities, should be broken up and sold.

When these leaders came to power in the mid-1800s, they made laws to sell these lands. Later, when Porfirio Díaz became president in 1877, he pushed for even more changes. He wanted to attract money from other countries for mining, farming, and ranching. This worked, and by 1910, most of Mexico's land was controlled by Mexican and foreign investors.

However, peasants (farmers) fought against these rich landowners during the Mexican Revolution. This led to land reform after the revolution, which created the ejido system. This system gave land back to communities for shared use. In the first few years, not much land was given out. But over time, the land reform led to many ejidos being created for communal use. Later, some ejidos were divided into smaller plots for individual families.

Contents

History of Land Ownership in Mexico

Over a long time, land in Mexico often ended up in the hands of private owners who farmed for profit. But this caused social and economic problems because a few people owned so much land. This led to reforms that tried to change things. Today, there's a trend away from land reform, and land is again being gathered into large businesses.

Ancient Times: How Land Was Used Before the Spanish Arrived

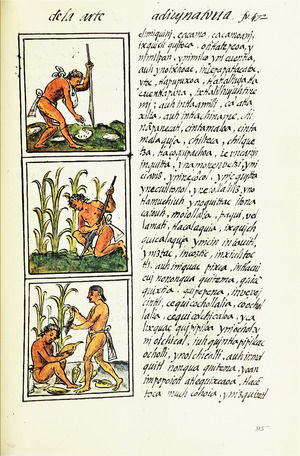

The fertile lands of central and southern Mexico were home to many people living in organized societies. They grew lots of food, which allowed some people to do other jobs besides farming. These communities lived in settlements and often shared land, though families usually worked their own plots.

During the Aztec period (around 1450 to 1521), the Nahua people of central Mexico had different names for types of land:

- Tlatocatlalli: Lands for the ruler.

- Tecpantlalli: Lands that supported temples.

- Pillalli: Private lands owned by nobles.

- Calpullalli: Lands owned by the calpulli, which was a local group of families.

Most common people had their own plots of land, often in different places. Families worked these plots, and the rights were passed down to their children. If a family didn't farm their land, they could lose the right to use it. People could also lose land because of gambling debts, which shows that land could be treated like private property.

It's interesting that there were lands called "purchased land" (in Nahuatl, tlalcohualli). In the Texcoco area, there were rules for selling land even before the Spanish arrived. This means that selling land was not a new idea after the Spanish conquest. Old records from the 1500s, written in Nahuatl, show that people kept track of these land types, including purchased land, and who owned them before.

Colonial Era: Spanish Rule Changes Land Ownership

When the Spanish took over central Mexico in the early 1500s, they mostly left the existing indigenous land ownership alone. They only removed lands that were used for Aztec gods. A Spanish judge in the 1500s, Alonso de Zorita, gathered a lot of information about the Nahua people and their land. He noted that land ownership was very diverse in central Mexico.

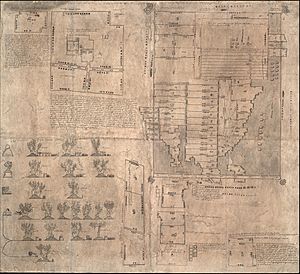

There are many documents about indigenous land ownership, including large estates held by indigenous lords (caciques), called cacicazgos. Disputes over land ownership started very early in the colonial period.

At first, many Spanish conquerors received grants of labor and tribute from indigenous communities. This system was called encomienda. These grants did not include land. The Spanish were more interested in the products and labor from the indigenous people.

However, the Spanish king slowly ended the encomienda system in the mid-1500s. At the same time, the indigenous population decreased due to diseases. More Spaniards came to Mexico, and they wanted European foods like wheat, fruits, and animals. So, Spaniards started buying land and getting labor in other ways. This was the beginning of large Spanish-owned farms.

Spaniards bought land from individual indigenous people and communities. They also took land illegally or claimed "empty" land (terrenos baldíos) and asked the king for grants to own it. Some indigenous nobles sold common land to Spaniards, treating it as their own private property. Some indigenous people were worried about this and specifically forbade selling land to Spaniards.

The Spanish king cared about the well-being of indigenous people. In 1567, he set aside land next to indigenous towns, called the fundo legal, which was legally owned by the community. This helped protect some indigenous lands. To protect indigenous legal rights, the Spanish king also created the General Indian Court in 1590. Here, indigenous people and communities could go to court to settle land disputes.

Indigenous communities suffered huge population losses from diseases. This meant there was more land than they needed for a while. Spaniards acquired land during this time. In the 1600s, indigenous populations began to recover, but they couldn't get back all the land they had lost. Indigenous communities sometimes rented land to Spanish haciendas, which later made those lands easier to take over.

In the 1700s, the Spanish king worried that too much land in Spain was owned by a few people and wasn't being used well. A Spanish thinker named Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos suggested reforms. He believed that breaking up large estates, selling Church land, and privatizing common lands would make farming more productive.

Jovellanos's ideas influenced Manuel Abad y Queipo, an important religious leader in New Spain. Abad y Queipo gathered a lot of information about farming in the late 1700s and shared it with Alexander von Humboldt. Humboldt included this information in his book about New Spain. Abad y Queipo believed that unfair land distribution was the main cause of social problems in New Spain.

The Spanish king didn't make big land reforms in New Spain. However, in 1767, the king expelled the wealthy Jesuits from his lands. In Mexico, the Jesuits had very successful haciendas that funded their missions and schools. These estates were sold, mostly to rich private landowners.

The rich landowners and the Catholic Church were closely connected financially. The Church received donations and managed loans for land. Small farmers had little access to loans, making it hard for them to buy or expand property. This favored large landowners.

In the early 1800s, the Spanish king tried to get money from the Church by demanding that people with Church mortgages pay back the full amount immediately. This threatened to crash the credit system for landowners. Abad y Queipo protested, saying it would "destroy the country’s credit system." He concluded that large, undivided haciendas and the lack of land for common people caused "deplorable effects for agriculture, for the population, and for the State."

After Mexico became independent in 1821, the special protections the Spanish king had given to indigenous people and their lands disappeared. This left indigenous people and their lands vulnerable.

Fight for Independence and Land Violence (1810–1821)

When Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla started the fight for independence in September 1810, many indigenous people and mixed-race people joined him. This happened in the Bajío region, which was a commercial farming area. This region didn't have many established indigenous communities. Instead, Spaniards created towns and large farms worked by people who didn't own land. These workers depended on the haciendas for jobs and food.

When Hidalgo called for a rebellion, his followers quickly grew to tens of thousands. They went from town to town, looting and attacking haciendas. The landowners couldn't stop them. Hidalgo had hoped to get support from Mexican-born elites, but the mob attacked all haciendas, whether owned by Spanish-born or Mexican-born people. Any support these elites might have had for independence disappeared. Even though land inequality fueled the violence, Hidalgo himself didn't have a clear plan for land reform at first. Only later did he say that lands rented by villages should be returned to their residents.

Hidalgo asked indigenous communities in central Mexico to join his movement, but they didn't. Some historians believe this is because the king had protected their rights and lands, making them loyal. Also, the relationship between indigenous communities and haciendas was often stable, giving them a reason to keep things as they were.

More successful in showing that peasant violence could achieve gains was the guerrilla warfare that continued after Hidalgo's defeat. These small, mobile groups undermined the colonial government's security. Their survival depended on support from nearby villages. While they didn't have a formal land reform plan, their actions showed the power of peasant struggle.

The alliance between former royalist officer Agustín de Iturbide and guerrilla leader Vicente Guerrero led to Mexico's independence in September 1821. This alliance was partly due to the political power that agrarian guerrillas had gained. The land-related violence during the independence era marked the beginning of more than a century of peasant struggle.

After Independence: 1821–1910

Peasants Fight to Get Land Back

After Mexico became independent, many indigenous communities fought to regain their land through rebellions. In the 1800s, there were serious revolts in places like the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Yucatan (the Caste War of Yucatan), and the Yaqui and Mayo regions (the Yaqui Wars). These conflicts lasted for many years, some into the 1900s.

During the Mexican Revolution, many peasants fought for the return of their community lands, especially in Morelos under Emiliano Zapata. The threat of armed struggle was key to how the Mexican government approached land reform after the revolution. Land reform helped stop peasant revolts and changed land ownership, which was very important for the new government.

Liberal Reforms and the Lerdo Law of 1856

Before the Reform War, liberal leaders came to power in Mexico and made a series of changes. One of these was the Lerdo Law, named after the Finance Minister, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada.

The Lerdo Law forced the sale of lands owned by groups, especially those of the Catholic Church and indigenous communities. The law didn't take the land directly. Instead, it required that these properties be sold to those who were renting them, with payments spread over 20 years. Properties not rented could be auctioned off. The Church and indigenous communities were supposed to receive the money from the sales, and the government would get a tax.

This law aimed to allow more individuals to own land, rather than institutions. The government hoped to make unused lands of the Church and indigenous communities more productive by distributing them to small owners. However, this didn't happen for indigenous communities. Most indigenous land was bought by large estates, making indigenous people even more dependent on these big farms.

The Porfiriato: Land Taken and Foreign Ownership (1876-1910)

During the presidency of Porfirio Díaz, Mexico underwent a huge modernization project. Díaz invited foreign business people to invest in Mexican mining, farming, and factories. The earlier Liberal Reform laws had already set the stage for ending group ownership of land. Díaz's government greatly expanded this by saying that "unoccupied lands" (terrenos baldíos) should be surveyed and opened for development by Mexicans and foreigners.

The government hired private companies to survey all land that hadn't been surveyed before. These companies kept one-third of the land they surveyed. The rest could then be sold. This was meant to give buyers clear ownership and encourage investment. For Mexicans who couldn't prove they owned their land, or who had informal rights to use pastures and forests, these surveys ended their common usage and put the land into private hands. The government's goal was to make the land more productive.

Many investors from the U.S., like William Randolph Hearst, bought land from survey companies or Mexican estate owners. Díaz's loyal friends and even his family also bought large areas of land. Land near railway lines became even more valuable because it could easily send products to markets.

The situation for landless Mexicans got much worse. By the end of Díaz's rule, almost all (95%) of villages had lost their lands. In Morelos, the growth of sugar plantations led to peasant protests against Díaz. These protests were a major reason for the start of the Mexican Revolution.

Calls for Land Reform

In 1906, the Liberal Party of Mexico (PLM) wrote down specific demands, many of which were included in the Mexican Constitution of 1917. Two important demands were:

- Landowners must make their land productive or risk losing it to the state.

- The government should give land to anyone who asks for it, as long as they use it for farming and don't sell it. There would be a limit on how much land one person could get.

A key person who influenced land reform was Andrés Molina Enríquez. He is considered the intellectual father of Article 27 of the 1917 Constitution. In his 1909 book, Los Grandes Problemas Nacionales (The Great National Problems), he analyzed Mexico's unequal land system and shared his ideas for reform.

Molina Enríquez had worked as a notary, where he saw firsthand how the legal system favored large estate owners. He noticed that small farmers (rancheros) were often more productive than huge haciendas. He believed that large estates were "inherently evil" and wanted to see more rancheros.

He concluded that Díaz's government had helped large haciendas grow, even though they weren't as productive as small farms. He also pointed out that large estates often paid very low taxes and took over more land than they legally owned. Many small farmers had unclear land titles or no title at all, putting them at risk of losing their land under Díaz's "vacant lands" law. Indigenous villages also lost their land, but through different processes.

Land Reform: 1911-1946

The Mexican Revolution reversed the trend of land being owned by a few. It started a long process of peasant movements that the new government tried to control. The power of the traditional landowners, who had supported Díaz, never fully recovered. The revolution's ideas made it impossible for the old kind of landlord rule to continue.

Revolutionary Peasant Movements

During the Mexican Revolution, two leaders carried out land reform without formal government action: Emiliano Zapata in Morelos and Pancho Villa in northern Mexico.

Francisco I. Madero, a wealthy landowner, promised to return village lands that had been illegally taken. But when Díaz fell and Madero became president, he did little about land reform. Zapata led peasants in Morelos, who divided large sugar haciendas into plots for farming. Zapata and others in Morelos wrote the Plan of Ayala, which called for land reform and led to their rebellion against the government. Unlike many other revolutionary plans, Zapata's was actually put into action. Villagers in areas he controlled got their lands back and also took over sugar plantations, dividing them up. This was the only major land reform during the Revolution.

Even after Zapata was killed in 1919, the land reform in Morelos couldn't be reversed. When Álvaro Obregón became president in 1920, he recognized the land reform in Morelos and gave Zapatistas control of the state.

The situation in northern Mexico was different. There were fewer small farmers and more large cattle haciendas. During the Porfiriato, the government gained more control, and hacienda owners started taking over lands that small farmers or military colonies used. The government hired companies to survey "empty lands," and these companies kept a third of the land. The rest was bought by wealthy landowners, especially the powerful Terrazas-Creel family.

In 1913, after Madero was killed, Pancho Villa joined the fight against Victoriano Huerta. As governor of Chihuahua, Villa issued decrees that put large estates under state control. They continued to operate as haciendas, with the money used to fund Villa's army and support soldiers' families. Villa's men were promised land after the Revolution. Villa also decreed that all large estates in the country would be divided among peasants, with some payment to the owners. Northerners wanted more than just a small plot for subsistence; they wanted enough land to be a rancho where they could farm or ranch independently. Although Villa was defeated in 1915, the Terrazas-Creel properties were not returned to them after the Revolution.

Land Reform Under Carranza (1915-1920)

Land reform was a big issue in the Mexican Revolution, but Venustiano Carranza, the leader of the winning side, was not eager to pursue it. However, in 1914, two important generals, Álvaro Obregón and Pancho Villa, urged him to create a land distribution policy.

One of Carranza's main helpers, Luis Cabrera Lobato, drafted the Agrarian Decree of January 6, 1915. This decree promised to provide land for those who needed it. The main idea was to reduce the appeal of Zapata's movement and give peasants access to land to earn extra money when they weren't working on haciendas. Cabrera presented the proposal as a military necessity to calm rebellious communities.

After Victoriano Huerta was defeated, the winning group split. Villa and Zapata, who wanted more radical land changes, opposed Carranza and Obregón. To defeat them, Carranza had to offer something to the peasants. His military units took over some haciendas to give land to villages that might support more radical ideas. However, the Agrarian Decree didn't call for taking over all lands. The lands given out were called ejidos, but they were new grants from the state, often of poor quality and smaller than what villages used to have.

Carranza's government set up a system to handle land reform, but in practice, it tried to limit big changes for peasants. Many landowners whose estates had been taken were given them back during Carranza's time. Villages that received land grants had to agree to pay the government for the land. Old documents proving village land claims were considered invalid. By the end of Carranza's presidency in 1920, the government was trying to prevent serious land reform or any peasant control over it. Carranza had only supported limited land reform as a strategy. However, he couldn't stop the adoption of Article 27 of the 1917 Constitution, which recognized villages' rights to land and the state's power over resources below the surface.

Under Obregón (1920-1924)

Álvaro Obregón, a wealthy landowner and brilliant general, became president after a coup against Carranza. Since the Zapatistas had supported him, he appeased them by stopping attempts to take back seized land from big sugar estate owners. However, his plan was to make the peasants dependent on the Mexican state. He saw land reform as a way to strengthen the new government.

During his presidency, it was clear that some land reform had to happen. Land distribution began almost immediately, affecting both foreign and large Mexican landowners. The process was very slow because Obregón generally didn't see it as a top priority. But to keep peace with the peasants, he started serious land reform. As president, Obregón distributed 1.7 million hectares (about 4.2 million acres) of land. Most of this land was not already cultivated, consisting of forests, pastures, mountains, and other uncultivable land (51%-64.6%). Rain-fed land was the next largest category (31.2% to 41.4%). The smallest amount of land distributed was irrigable land (4.2% to 8.2%).

When Obregón wanted his fellow general Plutarco Elías Calles to be his successor, Obregón and Calles promised land reform to get peasant support against their rival. Their side won, and when Calles became president in 1924, he did increase land distribution.

Calles and the Maximato (1924-1934)

Plutarco Elías Calles became president after Obregón in 1924. After Obregón was assassinated in 1928, Calles remained in power until 1934 as the jefe máximo (maximum chief), a period known as the Maximato. Like Obregón, Calles was not a strong supporter of land reform. He wanted to build a strong industrial sector in Mexico. In general, Calles blocked land reform measures and sided with landowners. During his presidency, the U.S. government was against land reform in Mexico because some of its citizens owned land and oil businesses there.

Although ejidos had been created under Obregón, Calles wanted them to become private holdings. Calles's government tried to expand farming by settling new areas or improving existing lands that weren't used efficiently. Giving loans to farming businesses benefited large landowners more than peasants. Government-built irrigation projects also helped them. Many revolutionary leaders, including Obregón and Calles, received large tracts of land, so they directly benefited from government support for agriculture.

During Calles's presidency (1924–28), 3.2 million hectares (about 7.9 million acres) of agricultural land were distributed. The largest category was non-agricultural land (forests, pastures, mountains, etc.), making up 60% to almost 80%. Rain-fed land was the next largest (20% to 35%). The smallest amount was irrigable land, only 3-4%.

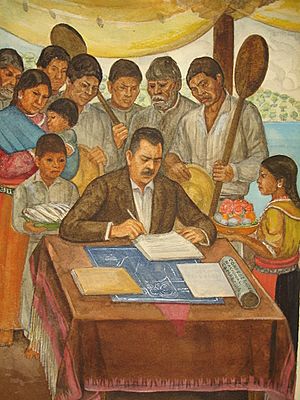

Cárdenas's Land Reform (1934-1940)

- Further information: Lázaro Cárdenas#Land Reform

President Lázaro Cárdenas is known for bringing land reform back to life, along with other changes that matched the spirit of the Revolution. Cárdenas distributed most of the land between 1936 and 1938. He was determined to give land to the peasants but also wanted to control the process himself, rather than letting peasants just seize land.

His most famous land takeover was in the Comarca Lagunera, an area with rich, irrigated soil. In 1936, about 448,000 hectares (over 1.1 million acres) of land were taken, with 150,000 hectares (about 370,000 acres) being irrigated. He ordered similar takeovers in other regions in 1937 and 1938.

Instead of dividing land into individual ejidos, which peasants often preferred, Cárdenas created collective ejidos. Communities were given land, but it was worked as a single unit. This was done for lands that produced commercial crops like cotton, wheat, and sugar, so they would continue to be profitable for Mexico and for export. Collective ejidos received more government support than individual ones.

Land reform had almost stopped in the early 1930s. But Cárdenas's reforms, starting in 1935, spread across the country. Cárdenas's alliance with peasant groups helped destroy the hacienda system. He distributed more land than all his revolutionary predecessors combined, a 400% increase. Cárdenas wanted peasants to be connected to the Mexican government. He did this by organizing peasant groups into the National Confederation of Peasants (CNC), which became part of the new political party structure he created.

During his time as president, he redistributed about 45,000,000 acres (180,000 km2) of land. About 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km2) of this was taken from U.S. citizens who owned farms. This caused some conflict between Mexico and the United States.

End of Land Reform: 1940-Present

Starting with the government of Miguel Alemán Valdés (1946–52), the land reform steps made by earlier governments began to be undone. Alemán's government allowed business owners to rent peasant land. This led to a situation called "neolatifundismo," where landowners built large private farms by controlling ejido land that was not being farmed by the peasants it was assigned to.

Echeverría's Land Reform

In 1970, President Luis Echeverría began his term by saying that land reform was over. But facing peasant revolts, he had to change his mind. He then started the biggest land reform program since Cárdenas. Echeverría made it legal to take over huge foreign-owned private farms, which were then turned into new collective ejidos.

Land Reform from 1991 to Today

In 1988, Carlos Salinas de Gortari became president. In December 1991, he changed Article 27 of the Constitution. This change made it legal to sell ejido land and allowed peasants to use their land as collateral for loans. However, land regulation is still permitted in Mexico by Article 27.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |