Florentine Codex facts for kids

The Florentine Codex is a huge research project from the 1500s. It was created by a Spanish Franciscan friar named Bernardino de Sahagún. He worked on it in Mesoamerica, which is now Mexico.

Sahagún's original title for the work was La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España. This means The Universal History of the Things of New Spain. The best copy is called the Florentine Codex because it is kept in Florence, Italy.

Sahagún worked with Nahua men who were his former students. They helped him research, organize, write, and edit his findings. He worked on this project from 1545 until he died in 1590.

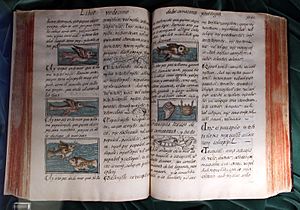

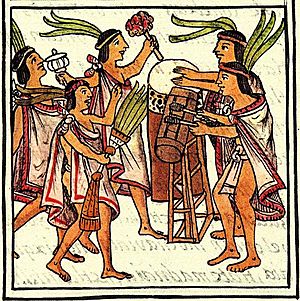

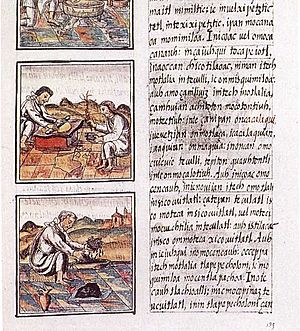

The work has 2,400 pages and is divided into twelve books. It also has over 2,000 amazing pictures drawn by native artists. These pictures show what life was like back then. The Codex tells us about the Aztec people's culture, beliefs, daily life, and nature. It is seen as one of the most important records of a non-Western culture ever made.

In 2002, Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson finished the first full English translation. This huge project took them 30 years! In 2012, you could see high-quality scans of the Florentine Codex online. It was added to the World Digital Library. In 2015, UNESCO declared Sahagún's work a World Heritage. This means it is very important for everyone to protect.

Contents

How the Codex Was Made

The Florentine Codex is a very complex document. It was put together and changed over many decades. It has three main parts:

- Text in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs.

- Text in Spanish.

- Many pictures.

The final version of the Codex was finished in 1569. Sahagún wanted to help other missionaries understand Aztec culture. He also wanted to create a rich Nahuatl vocabulary. And he aimed to record the amazing cultural history of the native people.

The pages are usually set up in two columns. The Nahuatl text is on the right side. A Spanish explanation or translation is on the left. Different voices and ideas are in these 2,400 pages. This means the document can sometimes seem to have different opinions.

Scholars think Sahagún was inspired by old writers like Aristotle and Pliny the Elder. These writers influenced how knowledge was organized in the Middle Ages.

What the Books Cover

The twelve books of the Florentine Codex are organized like this:

- Book 1: Gods, religious beliefs, and rituals.

- Book 2: Ceremonies.

- Book 3: The origin of the gods.

- Book 4: Fortune-telling and omens.

- Book 5: Omens from birds, animals, and insects.

- Book 6: Prayers, moral ideas, and beliefs.

- Book 7: The sun, moon, stars, and the Aztec calendar.

- Book 8: Kings and lords, how they were chosen, and how they ruled.

- Book 9: Merchants, who traded and explored new areas.

- Book 10: General history of people, their good and bad traits.

- Book 11: Earthly things like animals, plants, metals, and stones.

- Book 12: The story of the Spanish conquest from the Aztec point of view.

Book 12 is the only one that is strictly about history. It tells about the conquest of the Aztec Empire. It shows the view of the people from Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco.

Why Sahagún Did This Research

Sahagún was a missionary. His main goal was to teach the native people about Christianity. He said his work explained the "divine, or rather idolatrous, human, and natural things of New Spain." He thought of it like a doctor trying to cure a patient suffering from old beliefs.

He had three main goals for his research:

- To describe and explain the old native religions, beliefs, and gods. This helped friars understand these beliefs to teach the Aztecs.

- To create a dictionary of the Aztec language, Nahuatl. This dictionary gave more than just definitions. It explained the cultural background of the words, often with pictures. This helped others learn Nahuatl and understand its meaning.

- To record the great cultural heritage of the native people of New Spain.

Sahagún worked for many decades. He edited and revised his work over and over. He made several versions of the 2,400-page manuscript. Copies were sent to Spain and the Vatican in the late 1500s. They were meant to explain Aztec culture.

These copies were mostly lost for about 200 years. Then, a scholar found one in a library in Florence, Italy. Since then, many historians and experts have studied Sahagún's work. They have been exploring its details and mysteries for over 200 years.

Pictures in the Codex

The pictures in the Florentine Codex are a key part of the work. They were made to go along with the text. Many images show European influences. However, experts believe they were drawn by native scribe-painters called tlacuilo.

The pictures were put into spaces left open for them in the text. Some spaces were never filled. This suggests the manuscripts were not fully finished when sent to Spain. There are two types of images:

- Primary figures: These pictures add to the meaning of the text. There are about 2,000 of these.

- Ornamentals: These are decorative pictures.

The figures were first drawn in black outline. Color was added later. Scholars believe that about 22 different artists worked on the images. They found this by looking at how body parts like eyes and profiles were drawn.

The artists may have used European books with illustrations from the library at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco. Some images have Christian elements. For the Aztecs, adding color to an image made it come alive. It gave the image the true nature of what it showed. Color also helped share knowledge along with the image itself.

How Sahagún Gathered Information

Sahagún was one of the first people to create ways to gather and check information about native cultures. This method is now called ethnography. Ethnography is a scientific way to record the beliefs, behaviors, and worldview of another culture. It tries to explain them using that culture's own logic. This means scholars try to understand people very different from themselves.

Sahagún gathered knowledge from many different people. These people were experts in Aztec culture. He did this in the native language, Nahuatl. He also compared answers from different sources. He collected information from older, important native people. His trained helpers wrote down what was said in Nahuatl.

Some parts of the text seem like direct stories told by native people. Other parts clearly show that Sahagún asked specific questions to different people. Some sections are Sahagún's own notes or comments.

He used a special method with these parts:

- He used the native Nahuatl language.

- He asked elders and cultural leaders for information.

- He adapted his project to how Aztec culture recorded knowledge.

- He used the help of his former students from the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco. He even named them.

- He tried to capture the full reality of Aztec culture from its own viewpoint.

- He used questionnaires, but also accepted valuable information shared in other ways.

- He paid attention to how different meanings were given through Nahuatl language.

- He compared information from many sources to be sure it was correct.

- He collected information about the conquest from the viewpoint of the defeated Aztecs.

Because of these new methods, some historians call Sahagún the first anthropologist.

Most of the Florentine Codex is text in Nahuatl and Spanish. But its 2,000 pictures show vivid scenes of 16th-century New Spain. Some pictures directly support the text. Others are related to the topic. Some seem to be just for decoration. Some are colorful and large, taking up most of a page. Others are black and white sketches.

The pictures show amazing details about life in New Spain. But they don't have titles. It's not always clear how some pictures relate to the text next to them. They can be seen as a "third language" in the manuscript. Different artists worked on them. The drawings mix native and European art styles.

Many parts of the Codex describe similar items, like gods or types of people. They follow a consistent pattern. This makes scholars think Sahagún used a series of questionnaires for his interviews.

Questions for Research

For example, Sahagún might have used these questions for Book One, about the gods:

- What are the god's names, traits, or features?

- What powers did the god have?

- What ceremonies were done for this god?

- What did the god wear?

For Book Ten, "The People," a questionnaire might have been used for workers:

- What is the (trader, artisan) called and why?

- What special gods did they worship?

- How were their gods dressed?

- How were they worshipped?

- What do they make?

- How did each job work?

This book also described other native groups in Mesoamerica.

Sahagún was very interested in Nahua medicine. The information he collected is a major help to the history of medicine. He was likely interested because many people were dying from diseases at the time. Thousands died, including friars and students. Parts of Books Ten and Eleven describe the human body, diseases, and plant remedies. Sahagún named over a dozen Aztec doctors who helped write these sections.

A questionnaire like this might have been used for medicine:

- What is the name of the plant (or plant part)?

- What does it look like?

- What does it cure?

- How is the medicine made?

- How is it given to someone?

- Where is it found?

This section gives very detailed information. It tells about where plants grow, how to grow them, and their medical uses. It also tells about using animal products as medicine. The drawings in this section add important visual details. This information is useful for understanding the history of botany and zoology.

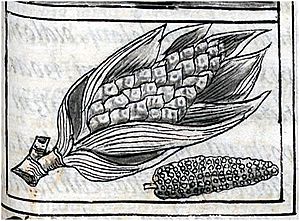

Book Eleven, "Earthly Things," has the most text and about half of the drawings. It describes the Aztec understanding of animals, birds, insects, fish, and trees in Mesoamerica.

Sahagún seemed to ask questions about animals like these:

- What is the animal's name?

- What animals does it look like?

- Where does it live?

- Why does it have this name?

- What does it look like?

- What habits does it have?

- What does it eat?

- How does it hunt?

- What sounds does it make?

Plants and animals are described with their behavior and natural homes. The Nahua people shared their information in a way that fit their worldview. For us today, this mix of ways can sometimes be confusing. Other sections include facts about minerals, mining, bridges, roads, and food crops.

The Florentine Codex is one of the most amazing social science projects ever done. Sahagún's methods for gathering information from inside a foreign culture were very unusual for his time. He recorded the worldview of the people of Central Mexico as they understood it. He did not just describe society from a European point of view. His work is unmatched by any other 16th-century book trying to describe native life. Sahagún was a Franciscan missionary, but he can also be called the Father of American Ethnography.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España para niños

In Spanish: Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España para niños

- Aztec codices

- Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco

- Bernardino de Sahagún

- Diego Durán

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |