Aztec codices facts for kids

Aztec codices (pronounced koh-dee-sez) are special ancient books or manuscripts. They were made by the Aztecs and their descendants in Mexico. These books were created both before the Spanish arrived (pre-Columbian) and during the time when the Spanish ruled (colonial period). They are often written in the Nahuatl language, which the Aztecs spoke.

Contents

What Are Aztec Codices?

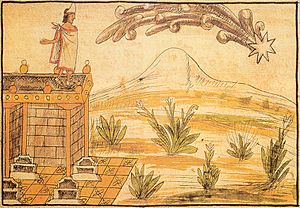

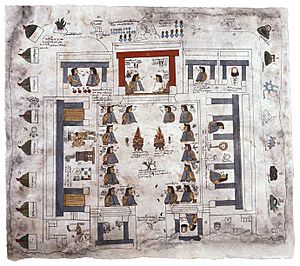

Before the Spanish arrived, the Mexica people (a group within the Aztecs) and their neighbors in the Valley of Mexico used painted books to record many parts of their lives. These painted manuscripts held important information about their history, science, land ownership, taxes (tribute), and sacred ceremonies.

For example, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a Spanish soldier, said that Moctezuma (the Aztec emperor) had a huge library full of these books. They were called amatl or amoxtli. A nobleman in Moctezuma's palace looked after them. Some of these books even listed what different towns had to pay as tribute.

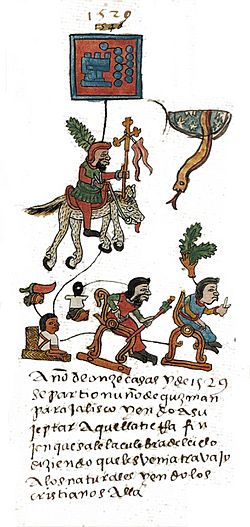

Even after the Spanish took over Tenochtitlan (the Aztec capital), the native people kept making these painted books. The Spanish even started to accept and use them as important records. This tradition of drawing and writing continued strongly for many years after the Europeans arrived, even into the early 1600s.

How Were They Made?

Since the 1800s, the word codex has been used for all ancient Mesoamerican painted books. But before the Spanish arrived, Aztec manuscripts were not exactly like the books we know today.

Aztec codices were usually made from long sheets of paper from fig bark (called amate) or stretched deerskins. These pieces were sewn together to make long, narrow strips. Some were also painted on large cloths. So, they came in different forms:

- Screenfold books: These folded up like an accordion.

- Strips: Called tiras, these were long, unfolded pieces.

- Rolls: Like scrolls.

- Cloths: Also known as lienzos.

We don't have any Aztec codices with their original covers. But from other similar books, we think Aztec screenfold books might have had wooden covers. These covers might have been decorated with beautiful turquoise mosaics.

Pictures and Writing

Aztec codices are different from European books because most of their information is shown through pictures. Experts have different ideas about whether parts of these books count as "writing."

Some think they are a mix of pictures and true writing, where some symbols stand for sounds. Others believe they are mostly a system of graphic communication, with only a few symbols representing sounds. Either way, everyone agrees that most of the information in these books was shared through images. Actual writing was mostly used for names.

Different Styles and Schools

Scholars have studied the different styles of Aztec pictorial manuscripts. One expert, Donald Robertson, said that the style before the Spanish conquest in Central Mexico was similar to that of the Mixtec people. This makes sense because the art of tlacuilolli (manuscript painting) was brought to the ancestors of the Texcocans by groups from Mixtec lands.

The Mixtec style often used a "frame line" to outline areas of color. Colors were usually put inside these lines, without any shading. Human figures could be divided into separate parts. Buildings were not realistic but followed certain rules. There was no sense of 3D space or perspective.

After the Spanish arrived, codices started to show European influences. They used contour lines that changed in width, and they tried to create illusions of 3D space and perspective.

Robertson also identified three main "schools" or regional styles within Aztec painting:

- School of Mexico Tenochtitlan: This style came from the capital city, Tenochtitlan. Early examples include the Matrícula de Tributos and Codex Boturini. Later examples include Codex Mendoza and Codex Telleriano-Remensis.

- School of Texcoco: This style came from the city of Texcoco. It includes documents related to the court of Nezahualcoyotl, like the Mapa Quinatzin and Codex Xolotl.

- School of Tlatelolco: This style came from Tlatelolco, a sister-city to Tenochtitlan. Examples include the Badianus herbal and the Florentine Codex.

How They Survived

Many ancient and colonial native texts were destroyed or lost over time. For example, when Hernán Cortés and his soldiers arrived in 1519, they found that the Aztecs kept books in temples and palace libraries. Juan Cano, another Spanish soldier, described books in Moctezuma's library that covered religion, family histories, government, and geography. He regretted their destruction by the Spanish.

Catholic priests also caused more loss by burning many surviving manuscripts. They thought these books were linked to idol worship.

However, a large number of manuscripts did survive! They are now kept in museums, archives, and private collections around the world. Experts have done a lot of work to study and classify them. A big project in the 1970s published a guide to Mesoamerican pictorial manuscripts, including many from the Valley of Mexico.

Only a few Aztec codices are thought to be from before the Spanish conquest. These include the Codex Borbonicus, the Matrícula de Tributos, and the Codex Boturini. Some experts believe these might show small signs of European influence, making their exact age debated.

Types of Information

The information in these manuscripts falls into several groups:

- Calendars: Showing dates and cycles.

- History: Recording events and timelines.

- Genealogy: Family trees and rulers.

- Maps: Showing land and places.

- Economy/Tribute: Lists of taxes and goods paid.

- Economy/Census: Records of people and property.

There are also special texts called Techialoyan manuscripts. These were written on native paper and usually describe meetings of local leaders and the boundaries of their towns.

Another type from the colonial era are Testerian manuscripts, which were religious texts. They contained prayers and memory aids. Sadly, some codices were even faked, and experts have had to identify these forgeries.

The Relaciones geográficas from the late 1500s are another important source. These were reports ordered by the Spanish king about different native towns. Each report usually included a map of the town, often drawn by a local native artist. Even though these were for Spanish use, they give us important information about the history and geography of native communities.

Important Aztec Codices

Some very important codices from the colonial period have been published with English translations:

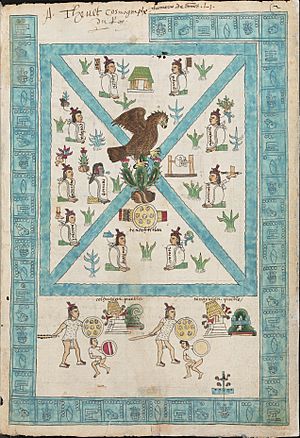

- Codex Mendoza: This book combines pictures with Spanish notes. It has three parts: a history of each Aztec ruler and their conquests, a list of tribute paid by different areas, and a general description of daily Aztec life. It is kept at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

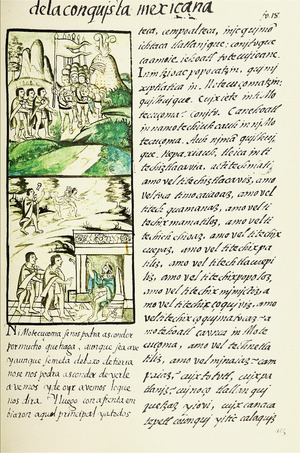

- The Florentine Codex: This huge project was led by a friar named Bernardino de Sahagún. He worked with native people to gather knowledge about Aztec religion, society, nature, and even a history of the Spanish conquest from the Aztec point of view. It resulted in 12 books, with both Nahuatl and Spanish text, and many illustrations by native artists.

- Works by Diego Durán: This Dominican friar used native pictures and talked to living people to create illustrated books on Aztec history and religion.

Colonial-era codices often have Aztec pictures or other visual elements. Some are written in the Latin alphabet in Classical Nahuatl or Spanish, and sometimes Latin. A few are entirely in Nahuatl without pictures. Even though very few pre-Hispanic codices survived, the tradition of the tlacuilo (codex painter) continued. Today, scholars have about 500 colonial-era codices to study.

Some written manuscripts also have pictures, like the Florentine Codex and Codex Mendoza. Others are only text in Spanish or Nahuatl.

List of Aztec Codices

Here are some notable Aztec codices:

- Anales de Tlatelolco: An early colonial-era history written in Nahuatl, without pictures. It tells about Tlatelolco's part in the Spanish conquest.

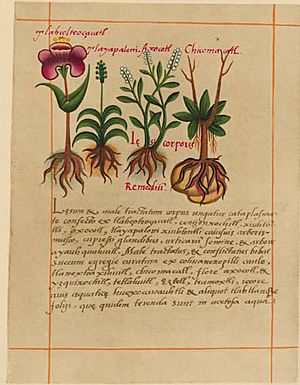

- Badianus Herbal Manuscript: This book describes the medicinal uses of different plants by the Aztecs. It was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano in 1552 from an original Nahuatl text.

- Codex Aubin: A pictorial history of the Aztecs from their journey from Aztlán, through the Spanish conquest, up to 1608. It also describes the massacre at the temple in Tenochtitlan in 1520.

- Codex Borbonicus: Written by Aztec priests after the Spanish conquest. It's mostly pictures and includes a divining calendar, a record of the 52-year cycle, and rituals.

- Codex Borgia: A pre-Hispanic ritual codex, named after Cardinal Stefano Borgia.

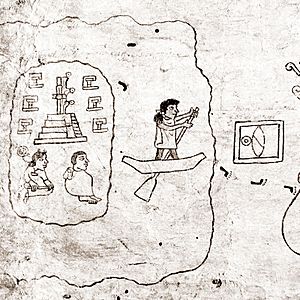

- Codex Boturini: Also called Tira de la Peregrinación. Painted between 1530 and 1541, it tells the story of the Aztec journey from Aztlán to the Valley of Mexico. It's a long sheet of fig bark paper folded like an accordion.

- Codex Cozcatzin: A post-conquest manuscript from 1572, with pictures and short descriptions in Spanish and Nahuatl. It lists land given by Itzcóatl and historical information about Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan.

- Codex Fejérváry-Mayer: A pre-Hispanic calendar codex.

- Codex Ixtlilxochitl: An early 1600s fragment detailing Aztec festivals and rituals. Each of the 18 months is shown with a god or historical figure.

- Codex Magliabechiano: Created in the mid-1500s, this religious document shows the 20 day-names, monthly feasts, the 52-year cycle, deities, and Aztec beliefs.

- Codex Mendoza: (See description above in "Important Aztec Codices").

- Codex Osuna: A mix of pictures and Nahuatl text, detailing complaints from native people against colonial officials.

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis: A calendar, divining guide, and history of the Aztec people.

- Codex Xolotl: A pictorial codex telling the history of the Valley of Mexico, especially Texcoco, from Xolotl's arrival to the defeat of Azcapotzalco in 1428.

- Codex Florentine: (See description above in "Important Aztec Codices").

- Mapa Quinatzin: A 16th-century mix of pictures and text about the history of Texcoco. It includes valuable information on their legal system, showing crimes and punishments.

See also

In Spanish: Códices mexicas para niños

In Spanish: Códices mexicas para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |