Amate facts for kids

Amate (pronounced ah-MAH-teh) is a special type of bark paper made in Mexico. People have been making it since ancient times, long before Europeans arrived. It was mostly used to create important books called codices.

Amate paper was very important for the Aztec Empire. They used it for talking, keeping records, and for religious ceremonies. But after the Spanish arrived and conquered Mexico, they mostly stopped people from making amate. They wanted people to use European paper instead.

Even though it was banned, amate paper making never completely disappeared. It stayed alive in secret, especially in the mountains of northern Puebla and Veracruz states. People in a small village called San Pablito, Puebla were known for making paper with "magical" powers for their rituals.

In the mid-1900s, experts from other countries started studying how amate was used in rituals. Then, the Otomi people in the area began selling the paper. Otomi artists started selling it in big cities like Mexico City. There, painters from the Nahua people in Guerrero started using amate paper to create new kinds of art. The Mexican government even helped promote this art.

Because of these changes, amate paper is now one of the most popular Mexican handmade crafts. You can find it sold all over Mexico and in other countries. The paintings made by Nahua artists on amate paper are very famous. But the Otomi paper makers are also known for their beautiful paper and for crafts like detailed cut-outs.

Contents

History of Amate Paper

Amate paper has a very long story. It has lasted so long because the materials to make it are still available. Also, the way it's made and used has changed over time to fit new needs. We can divide its history into three main parts: before the Spanish arrived, during the Spanish rule up to the 1900s, and from the late 1900s until today.

Ancient Times (Pre-Hispanic Period)

Making paper in ancient Mexico was similar to how it started in ancient China, which used mulberry trees. It was also like ancient Egypt, which used papyrus plants. We don't know exactly when or where paper making began in Mexico.

The oldest piece of amate paper found is from about 75 CE. It was found in Huitzilapa, Jalisco. This old paper was made from a type of fig tree called Ficus aurea. Ancient stone carvings also show pictures of things that look like paper. For example, a carving from the Olmec site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán shows a person wearing folded paper decorations. The oldest known book made from amate paper might be the Grolier Codex, which some experts believe is real and from the 1100s or 1200s.

Some experts think the Maya people were using bark paper for clothing around 300 CE. There are even Maya village names that mean "place where white bark is smoothed" or "over the white paper." In the 1980s, some Maya people in Chiapas were still making and using bark clothing. This suggests the Maya might have been the first to share the knowledge of bark paper making across southern Mexico and Central America.

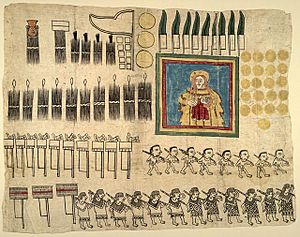

Amate paper was used the most during the Aztec Empire. The Aztecs controlled many lands, and over 40 villages had to give amate paper as a tax. This added up to about 480,000 sheets every year! Most of this paper was made in the area that is now Morelos state, where fig trees grow well. This paper was given to the Aztec rulers as gifts or rewards for brave warriors. It was also given to priests for religious ceremonies. The rest went to royal scribes to write books and keep records.

We don't know much about how paper was made in ancient times. But stone tools from the 500s CE have been found. These tools, called beaters, were used to pound the bark fibers. They are usually made of volcanic stone and have grooves to mash the fibers. Otomi artists still use similar beaters today. Early Spanish writings say that bark was soaked in water overnight. Then, the soft inner fibers were separated and pounded into flat sheets.

Amate paper was very important to the Aztecs. It was linked to power and religion, helping the Aztecs show their control. It was also a way for them to record important events and keep track of things like goods and money. Ancient books, called codices, were made by folding the paper like an accordion. Out of about 500 surviving codices, only about 16 were made before the Spanish conquest, and 4 of these are on bark paper.

Paper also had a sacred meaning. It was used in rituals with other items like incense and rubber. For ceremonies, bark paper was used in many ways: as decorations, as special bags, or as badges. It was also used to dress statues of gods, priests, and people who were sacrificed. Paper items like flags and very long sheets were burned as offerings. Sometimes, paper was cut into shapes like flags or trapezoids and painted with black rubber spots to honor specific gods.

Spanish Rule to the 1900s

When the Spanish arrived, they saw the native people making paper from bark, maguey plants, and palm fibers. But after the Spanish conquest, native paper lost its value. The Spanish preferred their own European paper. Also, because bark paper was used in native religions, the Spanish banned it. They said it was used for magic and witchcraft. This was part of their plan to convert native people to Catholicism. They even burned many codices, which held much of the native history and knowledge.

Only 16 of the 500 surviving codices were written before the Spanish conquest. The other books were written after the conquest, some on bark paper and some on European paper or animal skins. Many of these later books were made by missionaries, like Bernardino de Sahagún, who wanted to record native history and knowledge.

Even though bark paper was banned, it didn't completely disappear. In the early days of Spanish rule, there wasn't enough European paper, so native paper was sometimes used. Missionaries even used amate paper to create Christian images. Also, native people secretly continued to make paper for their rituals. In 1569, a friar saw native people offering paper and other items at a volcano lake. The groups who were best at keeping paper making alive lived in the rugged areas of La Huasteca, northern Veracruz, and some villages in Hidalgo. These areas were mostly home to the Otomi people, and their isolation helped them keep the tradition alive. Making paper in secret became a way to resist Spanish culture and keep their own identity.

From the 1900s to Today

By the mid-1900s, only a few small towns in the mountains of Puebla and Veracruz still knew how to make amate paper. San Pablito, Puebla, an Otomi village, was one of them. People there believed this paper had special power for rituals. Until the 1960s, only shamans made the paper, keeping the process a secret. They used it to cut out figures of gods for rituals.

However, these shamans met anthropologists who were interested in their paper and culture. Even though ritual paper cutting was still important, the use of amate paper was slowly decreasing. People were starting to use industrial paper for rituals instead. One reason amate became commercial was that shamans realized they could sell it. They started selling small cut-outs of bark paper figures in Mexico City.

When these figures were sold, amate paper became a product that could be bought and sold. The paper itself wasn't sacred until a shaman cut it for a ritual. This meant that making the paper and cutting it for non-ritual reasons was okay. So, a product once only for rituals could now be sold in the market. This also meant that anyone in San Pablito, not just shamans, could make the paper.

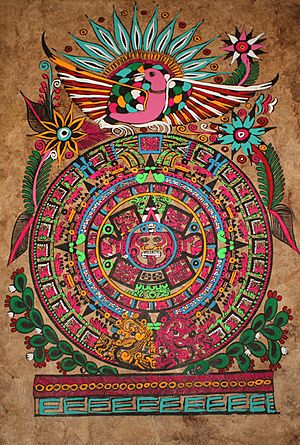

Most amate paper today is sold as a surface for paintings made by Nahua artists from Guerrero state. There are different stories about how painting on bark paper started. But we know that both Nahua and Otomi artists sold crafts in Mexico City in the 1960s. The Otomi sold paper and other crafts, and the Nahua sold their traditional painted pottery. The Nahua artists then started painting their pottery designs onto amate paper. This paper was easier to carry and sell. The Nahua called these paintings "amatl," which is their word for bark paper. Today, this word is used for all crafts made with the paper.

The new paintings became very popular right away. At first, the Nahua artists bought almost all the paper the Otomi made. Painting on bark paper quickly spread to many villages in Guerrero. By the late 1960s, it became the most important way to earn money in eight Nahua villages. Each Nahua village developed its own painting styles, based on their pottery traditions.

The rise of amate paper happened when the government started to encourage indigenous crafts, especially to help tourism. An agency called FONART helped distribute amate paper. They even bought all the Otomi paper for a couple of years to make sure the Nahua had enough. This was very important for selling amate crafts in Mexico and other countries.

Since then, the Nahua are still the main buyers of Otomi amate paper. But the Otomi have also started making different types of paper and their own products to sell. Today, amate paper is one of Mexico's most widely sold crafts. It has also gained attention from artists and experts. In 2006, an annual event called the "Encuentro de Arte in Papel Amate" (Art in Amate Paper Meeting) started in San Pablito. It includes art shows and traditional dances. The Museum of Popular Art even had an exhibit comparing amate and papyrus paper.

San Pablito: The Amate Paper Village

While amate paper is made in a few small villages, only San Pablito in Puebla makes it to sell commercially. San Pablito is a village in the mountains of Puebla. Making paper is the main way people in San Pablito earn money. This has helped reduce poverty in the village. Before, people lived in small wooden houses, but now they have bigger houses made of block.

The paper makers in San Pablito keep their process a secret. They don't want outsiders to copy their work. Besides helping the paper makers, this craft also provides jobs for more people who harvest bark. These bark collectors now work in a large area of the Sierra Norte de Puebla region. The village makes a lot of paper, still using mostly ancient methods and different types of trees. About half of this paper is still sold to Nahua painters in Guerrero.

Making paper has brought money and also political power to the Otomi people of San Pablito. It is now the most important village economically in its area. The last three local governments have been led by an Otomi person, which didn't happen before. However, most of the paper making is done by women. This is because many men still leave the village to work, often in the United States. In many homes in San Pablito, families combine these two sources of income.

Ritual Uses of Amate Paper

Even though amate paper is sold commercially in San Pablito, it still has a special ritual meaning there and in other areas. In these communities, making and using paper for rituals is similar. Figures are cut from light or dark paper. Each figure and color has a special meaning.

There are two main types of paper. Light or white paper is used for figures of gods or humans. Dark paper is linked to evil characters or magic. In some places, light paper is made from mulberry trees, and dark paper is made from fig trees. The older the tree, the darker the paper.

Ritual paper becomes sacred only when shamans cut it during a ceremony. The way it's cut is most important, not necessarily how artistic it looks. In San Pablito, the cut-outs are of gods or spirits from their native beliefs, never Catholic figures. Most of the time, these ceremonies are for asking for good crops or health. As farming becomes less important, requests for health and protection are more common.

In other areas, like Chicontepec, cut-outs are related to gods or spirits linked to nature, like lightning or rain. Those cut from dark paper are called "devils" or represent evil spirits. But figures can also represent living or dead people. Figures made of light paper represent good spirits and people who make promises. Female figures have special hair. Some figures have four arms and two heads, or animal heads and tails. Figures with shoes might represent people who died in fights or accidents. Those without shoes might represent indigenous people or good people who died from sickness or old age. Bad spirits made of dark paper are burned in ceremonies to end their bad influence. Good spirits made of light paper are kept as amulets (lucky charms).

We don't know exactly when these paper cut-outs started. They might go back to ancient times, or they might have started after the Spanish conquest. It was easy to carry, make, and hide them. Many of the religious ideas behind the cut-outs do come from ancient beliefs. During Spanish rule, the Otomi people were often accused of witchcraft because they used these cut-outs. Today, some cut-out figures are sold as crafts or folk art. Industrial paper is also sometimes used for rituals now. Cut-outs made for sale are often different from those made for rituals, to keep the sacred part separate.

In San Pablito, anyone can make and cut paper, not just shamans. However, only shamans can perform the paper cutting rituals. The villagers also keep the exact paper making techniques secret from outsiders. A well-known shaman who uses cut-outs is Alfonso García Téllez from San Pablito. He says that his cutting rituals are not witchcraft. Instead, they are a way to honor nature spirits and help those who have died. García Téllez also creates books with cut-outs of Otomi gods. He has sold these and shown them in museums.

Amate Paper Products

Amate paper is one of many paper crafts in Mexico. It has only been sold as a product since the 1960s. Before that, it was mostly used for rituals. Amate paper has been successful because it can be used to make many different products. These products use both traditional Mexican craft designs and newer ideas. Because the paper is so versatile, both Otomi artists and others have created many different items to please buyers.

The paper is sold plain, dyed in many colors, and decorated with things like dried leaves and flowers. Even though the Nahua people of Guerrero are the main buyers of Otomi paper, other large buyers use it to make lampshades, notebooks, furniture covers, wallpaper, and fancy stationery. The Otomi themselves have started making paper products like envelopes, bookmarks, and invitation cards. They also make cut-out figures, often based on traditional ritual designs. The Otomi have even created two types of paper: standard quality and a higher-end paper for famous Nahua artists and others who value its special qualities. This means some paper makers are becoming known as master craftspeople.

Otomi paper makers usually sell their paper to a few wholesalers. This is because they might not speak much Spanish or have many contacts outside their village. About ten wholesalers control the distribution of half of all Otomi paper. These wholesalers, and artists like the Nahua who use the paper, have more contacts. So, amate products are sold widely in Mexico and other countries.

Amate paper products are still sold on streets and in markets in Mexico, especially in places where tourists visit. But through wholesalers, the paper also ends up in craft stores, open markets, special shops, and online. Much of it is used for paintings, and the best of these have been shown in museums and galleries around the world. The paper is sold directly to tourists in San Pablito. It's also sold in shops in cities like Oaxaca, Tijuana, Mexico City, Guadalajara, Monterrey, and Puebla. It is also sent to the United States, especially to Miami.

However, about 50 percent of all Otomi paper is still made in the standard size of 40 cm by 60 cm. This is sold to Nahua painters from Guerrero. This market is what made the large-scale selling of amate paper possible. About 70 percent of all crafts made by these Otomi and Nahua artists are sold in Mexico. About 30 percent are sold to other countries. Since most amate paper is sold for paintings, many people think the Nahua also make the paper.

The amate paper paintings combine Nahua and Otomi traditions. The Otomi make the paper, and the Nahua have adapted their painting styles, which they used for ceramics, to the paper. The Nahuatl word "amate" is used for both the paper and the paintings. Each Nahua village has its own painting style. These styles were first developed for ceramics and sold in tourist areas like Acapulco in the 1940s. The idea to paint on amate paper came in the 1960s. It quickly spread to many villages and became the main way to earn money in eight Nahua villages in Guerrero. The paper is special because it reminds people of Mexico's ancient past, along with the traditional designs painted on it.

The success of these paintings led the Nahua to buy almost all the Otomi's paper in the 1960s. It also caught the government's eye. The government started to promote indigenous crafts to tourists. The FONART agency helped for two years, buying Otomi paper to make sure the Nahua had enough supplies for painting. This was very important for selling the paintings and paper in Mexico and other countries. It also helped make this "new" craft seem real and important, using symbols of past and present native peoples as part of Mexican identity.

The paintings started with traditional pottery designs, and many still use them. But artists have also tried new things. Painted designs first focused on birds and flowers. Then, artists started painting landscapes, especially scenes of rural life like farming, fishing, weddings, and religious festivals. Some painters have become famous for their work. For example, Nicolás de Jesús has gained international fame for his paintings. His art often shows themes like death, the struggles of indigenous people, and local popular culture. Other artists have found ways to work faster, like using silk-screen techniques to make many copies.

While Nahua paintings are the most important craft made with amate paper, the Otomi have also started selling their detailed cut-out figures. This began with shamans making small books with tiny cut-outs of gods and handwritten explanations. These started to sell, and their success led to them being sold in markets in Mexico City. The Otomi still sell cut-outs with traditional designs, but they have also tried new designs, paper sizes, colors, and types of paper. These cut-outs include different gods, especially those related to beans, coffee, corn, pineapples, tomatoes, and rain. However, these cut-outs are not 100% exact copies of the ritual ones. Changes are made to keep the ritual aspect separate. New ideas include books and cut-outs of suns, flowers, birds, abstract designs from traditional beadwork, and even Valentine hearts with painted flowers. Most cut-outs are made of one type of paper, then glued onto a background of a different color. They come in many sizes, from tiny ones in booklets to large ones that can be framed like paintings. Selling these paper products has brought tourists to San Pablito from all over Mexico and even from other countries.

How Amate Paper is Made

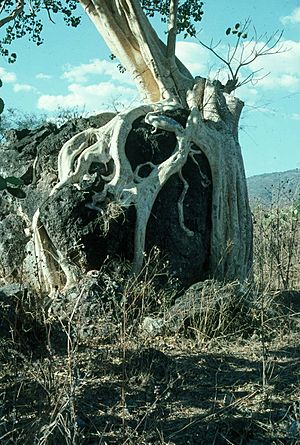

Even with some small changes, amate paper is still made using the same basic steps as in ancient times. The process starts by getting bark for its fibers. Traditionally, this bark comes from fig trees because their bark is easiest to work with. Some large fig trees are considered sacred. The best bark comes from trees that are at least 25 years old. At that age, the bark peels off easily and doesn't harm the tree as much. Other trees, like mulberry, don't need to be as old.

The main types of fig trees used are F. cotinifolia, F. padifolia, and F. petiolaris. Other trees like mulberry are also used. The softer inner bark is preferred, but other parts are used too. Outer bark and bark from fig trees usually make darker paper. Inner bark and mulberry bark make lighter paper. It's best to cut bark in the spring when it's new, as this causes less damage to the tree.

Because so much paper is sold now, people have to search a wider area for suitable trees. This means that people from outside San Pablito usually collect the bark. They come to the village at the end of the week. The paper makers usually buy fresh bark and then dry it for storage. Dried bark can be kept for about a year.

When amate paper started to be sold commercially, most people in the village became involved in making it. However, in the 1980s, many men started leaving to work in other places, mostly the United States. They sent money home, which became the main source of income for San Pablito. This made paper making a secondary job, mostly done by women. The basic tools are stones to beat the fibers, wooden boards, and pans to boil the bark. These tools come from outside San Pablito.

In ancient times, bark was soaked in water for a day or more to soften it. A newer method, used since at least the 1900s, is to boil the bark, which is faster. To make boiling even quicker, people used to add ashes or lime to the water. Now, they use a chemical called caustic soda. With caustic soda, the bark boils for three to six hours. The whole process, including setup, takes half a day to a full day. It can only be done on dry days and needs constant attention. About 60 to 90 kg of bark are boiled at a time with 3.5 kg of caustic soda. The bark needs to be stirred all the time. After boiling, the bark is rinsed in clean water.

The softened fibers are kept in water so they don't rot. They need to be processed quickly. At this stage, chlorine bleach might be added to make the paper lighter or to create a marbled look with different shades. This step is often needed because there isn't enough naturally light bark. If the paper is to be colored, strong industrial dyes are used. These can be purple, red, green, or pink, depending on what customers want.

Wooden boards are used to shape the paper. They are rubbed with soap so the fibers don't stick. The fibers are spread out on the boards and pounded together into a thin, flat sheet. The best paper is made with long fibers arranged in a grid pattern on the board. Lower quality paper is made from shorter fibers arranged more randomly, but still pounded flat. This pounding process releases natural sugars in the fibers that act like a glue. Fig tree bark has a lot of this substance, which makes the paper strong but flexible. During the pounding, the stones are kept wet so the paper doesn't stick. The finished flat sheet is then usually smoothed with rounded orange peels. If there are any small holes after pounding, they are filled by gluing small pieces of paper.

The pounded sheets are left on their boards and taken outside to dry. Drying time depends on the weather. On dry, sunny days, it can take an hour or two. But in humid conditions, it can take days. If the dried sheets are sold to wholesalers, they are simply bundled. If they are sold directly to customers, the edges are trimmed with a blade.

The paper making process in San Pablito has changed to make paper as fast as possible. Work is divided, and new tools and ingredients are used. Most paper making is done by families in their homes. If it's a part-time job, it's done sometimes, usually by women and children. Recently, larger workshops have started. These workshops hire artists to do the work, supervised by the family who owns the business. These are often started by families who have invested money sent home by migrant workers. Most of the paper made is plain sheets of 40 cm by 60 cm. But the larger workshops make a wider variety of products, including giant sheets that are 1.2 by 2.4 meters in size.

Environmental Concerns

Selling amate paper widely has caused some environmental problems. In ancient times, bark was only taken from the branches of older trees, which allowed the trees to grow back. Fig trees should ideally be at least 25 years old before their bark is cut. At that age, the bark almost peels off by itself and doesn't hurt the tree as much. Other trees, like mulberry, don't need to be as old. But the demand for large amounts of bark means it's now taken from younger trees too. This is harming the environment in northern Puebla. It also forces bark collectors to take bark from other types of trees and from a wider area.

Another problem is using caustic soda and other industrial chemicals in the process. These chemicals can get into the environment and water supply. They can also harm the artists if not handled carefully.

Several organizations are working to make amate paper making more sustainable. These include Fondo Nacional para el Fomento de las Artesanías, universities, and craft institutes. One goal is to manage how bark is collected. Another is to find a replacement for caustic soda that softens the fibers without harming the environment or the artists' health. They have made progress, like finding ways to use bark from new types of trees.

Also, the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social is pushing for a plan to plant more trees. This would help ensure a steady and sustainable supply of bark for the future.

See also

In Spanish: Papel amate para niños | (No images were moved to this section as all original images were kept in their respective sections.)

In Spanish: Papel amate para niños | (No images were moved to this section as all original images were kept in their respective sections.)

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |