Maya codices facts for kids

Maya codices are special folding books made by the ancient Maya people. They were written in Maya hieroglyphic script, which is a system of pictures and symbols. These books were made on a unique type of paper called bark paper. This paper came from the inner bark of a wild fig tree.

Maya scribes, who were like artists and writers, created these books. They worked under the guidance of gods like the Tonsured Maize God and the Howler Monkey Gods. Sadly, most of these amazing books were destroyed by Spanish explorers and Catholic priests in the 1500s. The few codices that survived are named after the cities where they ended up. The Dresden Codex is usually seen as the most important one.

The Maya developed their bark paper, which they called huun, around the 5th century. This was about the same time that folding books became popular in the Roman world. Maya paper was very strong and good for writing on, even better than papyrus.

As Michael D. Coe once said, "Our knowledge of ancient Maya thought must represent only a tiny fraction of the whole picture, for of the thousands of books in which the full extent of their learning and ritual was recorded, only four have survived to modern times." This shows how much valuable information was lost.

Contents

Why Were Maya Books Destroyed?

Many Maya books existed when the Spanish arrived in the Yucatán area in the 1500s. Most of them were burned by Catholic priests. For example, in July 1562, Bishop Diego de Landa ordered many books in Yucatán to be destroyed. He wrote that the books contained "superstition and lies of the devil." The Maya people were very sad about this.

These codices were the main written records of the Maya civilization. They contained much more information than the carvings on stone monuments and stelae. They likely covered many topics, similar to what is seen on painted pottery. In 1540, Alonso de Zorita saw many such books in the Guatemalan highlands. He said they "recorded their history for more than eight hundred years back."

A Dominican friar named Bartolomé de las Casas was upset when he learned these books were destroyed. He said, "These books were seen by our clergy, and even I saw part of those that were burned by the monks." The last codices were destroyed in Nojpetén, Guatemala, in 1697. This was the last Maya city conquered by the Spanish. When these books were lost, a lot of Maya history and knowledge disappeared forever.

The Surviving Maya Codices

Only three complete Maya codices have been saved:

- The Dresden Codex (74 pages, 3.56 meters long).

- The Madrid Codex (112 pages, 6.82 meters long).

- The Paris Codex (22 pages, 1.45 meters long).

A fourth codex, the Grolier Codex (10 pages), was once thought to be Maya-Toltec and was debated for a long time. However, in 2015, research finally proved it was real. It is now called the Maya Codex of Mexico.

The Dresden Codex

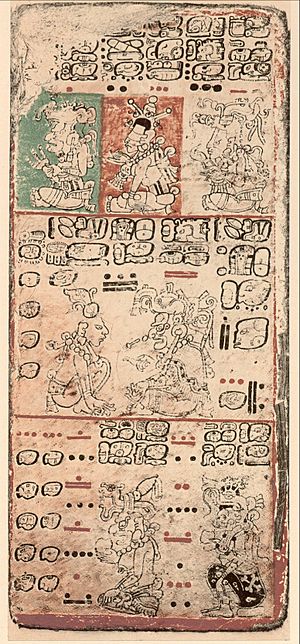

The Dresden Codex is kept in the state library in Dresden, Germany. It is considered the most detailed and important example of Maya art. Many parts of it are about rituals and calendars. Others are about astronomy, like eclipses and the cycles of Venus.

The codex is a long sheet of paper folded like a screen, making a book with 39 pages written on both sides. It was probably written between the 12th and 14th centuries. It arrived in Europe and was bought by the royal library in Dresden in 1739. A perfect copy of it, made with the same huun paper, is on display in Guatemala City.

About 65% of the Dresden Codex pages show detailed astronomical tables. These tables focus on eclipses, the longest and shortest days of the year (equinoxes and solstices), and the movements of Mars and Venus. The Maya used these observations to plan their calendar, farming, and religious events. In the book, Mars is shown as a deer with a long nose, and Venus is a star.

Pages 51–58 are tables that predicted solar eclipses for 33 years in the 8th century. However, their predictions for lunar eclipses were not as good. Pictures of snakes eating the sun represent eclipses in the book. The symbols for eclipses appear about 40 times, showing how important they were to the Dresden Codex.

The first 52 pages of the codex are about divination, which is like fortune-telling. Maya astronomers used the codex to keep track of days and to figure out the causes of sickness or bad luck. Many gods and goddesses appear in the Dresden Codex, but the Moon Goddess is the only one shown as neutral. She is mentioned more than any other god in the first 23 pages.

Between 1880 and 1900, a librarian named Ernst Förstemann figured out the Maya numerals and the Maya calendar in the codex. He realized it was an ephemeris, which is a table that shows where planets and stars will be on certain dates. Later studies have decoded these tables, which include records of the Sun and Moon cycles, eclipse tables, and all the planets visible without a telescope.

The Madrid Codex

The Madrid Codex was found in Spain in the 1860s. It was in two separate parts that were found in different places. It is also called the Tro-Cortesianus Codex, named after these two parts. The National Archaeological Museum in Spain got one part in 1888 and the other in 1872. The second part was bought from a book collector who said he got it in Extremadura. Many Spanish conquerors, like Francisco de Montejo and Hernán Cortés, came from Extremadura. So, it's possible one of them brought the codex back to Spain. The museum director named one part after Hernán Cortés, thinking he might have brought it.

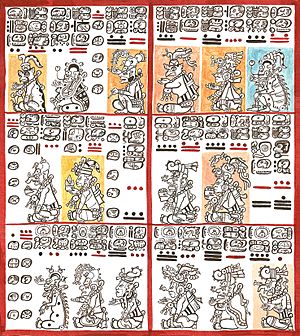

The Madrid Codex is the longest of the Maya codices that still exist. It mainly contains almanacs and horoscopes. These were used by Maya priests for ceremonies and to predict the future. It also has astronomical tables, but fewer than the Dresden Codex. Experts believe that many scribes, perhaps eight or nine, worked on this codex. They were likely priests.

Some experts thought the Madrid Codex was made after the Spanish conquest. However, most evidence shows it was made before the conquest. It was probably created in Yucatán. J. Eric S. Thompson believed it came from western Yucatán and was made between 1250 and 1450 AD. Other scholars say its style is similar to paintings found at Chichen Itza and Tulum.

The Paris Codex

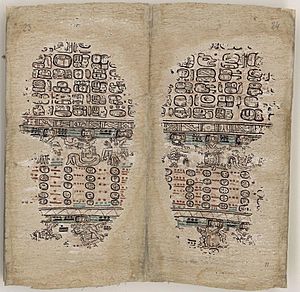

The Paris Codex contains predictions for different time periods in the Maya calendar. It also has a Maya zodiac, which is like a star chart. This makes it similar to the Books of Chilam Balam, which are Maya prophecy books. The codex first appeared in 1832 when it was bought by France's Imperial Library in Paris.

Its permanent rediscovery is credited to a French scholar named Léon de Rosny. In 1859, he found the codex in a basket of old papers in a chimney corner at the National Library, where it had been forgotten. Because of this, it is in very poor condition. It was wrapped in paper with the name Pérez on it. De Rosny first called it the Codex Peresianus (Codex Pérez), but it became more widely known as the Paris Codex. De Rosny published a copy of it in 1864. It is still kept at the National Library of France.

The Maya Codex of Mexico

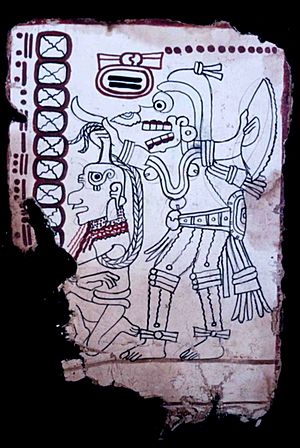

This codex was discovered in 1965 and was first called the Grolier Codex. It was renamed the Maya Codex of Mexico in 2018. The codex is broken into pieces, with 11 pages remaining out of what was probably a 20-page book. Since 2016, it has been kept at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. It is the only one of the four Maya codices that is still in the Americas.

Each page shows a hero or a god facing left. At the top of each page is a number, and down the left side is a list of dates. The pages are much simpler than those in the other codices and don't give much new information. For a long time, people argued if it was real. But tests in the early 21st century showed it was authentic. In 2018, Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History confirmed it was a real Pre-Columbian codex. It is believed to have been made between 1021 and 1154 CE.

Other Maya Books and Fakes

Sometimes, when archaeologists dig at Maya sites, they find rectangular lumps of plaster and paint. These are the remains of codices where the paper has rotted away. A few of these lumps have been saved, hoping that future technology might help us read them. The oldest Maya codices found by archaeologists were buried with people in places like Uaxactun and Copán. Sadly, all of these have turned into unreadable masses.

Since the early 1900s, some fake Maya codices have been made. Two detailed fakes were owned by William Randolph Hearst. While fake codices usually don't fool serious scholars, the Grolier Codex (now Maya Codex of Mexico) was an exception for a while. Its paper seemed old, and some famous Maya scholars believed it was real. However, other experts pointed out many mistakes and odd things in the pictures and symbols. They argued it didn't make sense for Maya art or for astrological use. Even though their arguments were strong, scholars still debate its authenticity.

See also

In Spanish: Códices mayas para niños

In Spanish: Códices mayas para niños