Bartolomé de las Casas facts for kids

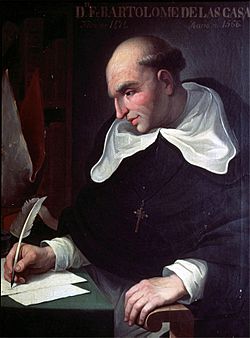

Quick facts for kids Bartolomé de las Casas |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of Chiapas | |

|

|

| Province | Tuxtla Gutiérrez |

| See | Chiapas |

| Enthroned | 13 March 1544 |

| Reign ended | 11 September 1550 |

| Other posts | Protector of the Indians |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1510 |

| Consecration | 30 March 1554 by Bishop Diego de Loaysa, O.R.S.A. |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Bartolomé de las Casas |

| Born | 11 November 1484 Seville, Crown of Castile |

| Died | 18 July 1566 (aged 81) Madrid, Crown of Spain |

| Buried | Basilica of Our Lady of Atocha, Madrid, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Occupation | Hacienda owner, priest, missionary, bishop, writer |

| Signature |  |

Bartolomé de las Casas (born November 11, 1484 – died July 18, 1566) was a Spanish priest, friar, and bishop in the 1500s. He is famous as a historian and someone who worked to change society. He first came to the Americas as a regular person, then became a Dominican friar and priest. He was the first official "Protector of the Indians" and the first Bishop of Chiapas.

Las Casas wrote many books, including A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. In his writings, he described the harsh treatment of Native Americans by Spanish settlers during the early years of colonization in the West Indies.

When he first arrived, Las Casas was a Spanish settler and even owned Native American slaves. But he soon realized the terrible things colonists were doing to the native people. In 1515, he freed his slaves and gave up his encomienda (a system where Spanish settlers were given control over Native American labor). He then started speaking out to King Charles V to protect the rights of Native Americans.

At first, he suggested using African slaves instead of Native Americans in the colonies. He didn't know how cruelly Africans were being enslaved. Later in his life, he changed his mind, believing all forms of slavery were wrong. In 1522, he tried to start a peaceful colony in Venezuela, but it failed. Las Casas then joined the Dominican Order and became a friar. He spent ten years away from public life, working as a missionary among the Maya in Guatemala. He also debated with other church leaders about the best way to introduce Christianity to the native people.

Las Casas traveled back to Spain to find more missionaries. He kept fighting to end the encomienda system. He won a big victory when the New Laws were passed in 1542. These laws aimed to protect Native Americans. He was made Bishop of Chiapas, but he only served a short time. He had to return to Spain because many Spanish settlers and encomenderos (those who benefited from the encomienda system) opposed the New Laws and his policies. He spent the rest of his life in the Spanish court, where he had a lot of influence on issues related to the Americas.

In 1550, he took part in the Valladolid debate. In this debate, Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda argued that Native Americans were less than human and needed Spanish masters. Las Casas strongly disagreed, arguing that they were fully human and that forcing them into slavery was wrong.

Bartolomé de las Casas spent 50 years fighting against slavery and the abuse of native people. He tried to convince the Spanish court to adopt a more humane way of colonizing. Unlike some other priests, he was against destroying the native peoples' books and writings. Even though he didn't completely change Spanish views, his efforts did improve the legal rights of Native Americans. He also made people think more about the right and wrong of colonialism.

Contents

Bartolomé de las Casas: Champion of Justice

Early Life and Journey to the Americas

Bartolomé de las Casas was born in Seville, Spain, on November 11, 1484. For a long time, people thought he was born in 1474, but later research showed the correct year. His father, Pedro de las Casas, was a merchant.

Las Casas first saw Native Americans in 1493 when Christopher Columbus returned to Seville. He saw seven Native Americans, along with colorful parrots and artifacts. His father, Pedro, went on Columbus's second trip and brought a young Native American back for his son in 1499.

In 1502, Las Casas traveled with his father to the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). He became a hacendado (landowner) and slave owner. He took part in raids and military actions against the native Taíno people. In 1506, he went back to Spain to finish his law studies. He became a deacon that year and a priest in 1507.

In 1510, a group of Dominican friars arrived in Santo Domingo. They were shocked by the unfair treatment of Native Americans. They refused to hear confessions from slave owners. Las Casas was one of those denied confession. In 1511, a Dominican preacher named Fray Antonio de Montesinos gave a powerful sermon. He asked the colonists, "By what right do you keep these Indians in such cruel slavery? With what authority have you waged such terrible wars against these peaceful people?" Las Casas, at first, argued against the Dominicans. But soon, his views would change.

A Change of Heart: Fighting for Native Rights

In 1513, Las Casas went to Cuba as a chaplain during its conquest. He saw many terrible acts committed by the Spanish against the native Ciboney and Guanahatabey people. He later wrote, "I saw here cruelty on a scale no living being has ever seen or expects to see." Las Casas and a friend were given an encomienda with gold and slaves. For a few years, he was both a colonist and a priest.

In 1514, while studying a religious text, Las Casas became convinced that the Spanish actions in the Americas were wrong and unjust. He decided to free his slaves and give up his encomienda. He began to preach that other colonists should do the same. When people resisted his ideas, he knew he had to go to Spain to fight for the native people. He left for Spain in September 1515.

Becoming the "Protector of the Indians"

Las Casas arrived in Spain hoping to convince King Ferdinand to end the encomienda system. Many powerful people in Spain benefited from the wealth coming from the Americas. King Ferdinand died in 1516, so Las Casas had to speak to the new regents (people who rule for a young king). He wrote a report called "Memorial de Remedios para Las Indias" in 1516. In this early work, he suggested bringing African slaves to replace Native American labor. He later regretted this idea, realizing all slavery was wrong.

The regents were worried by Las Casas's descriptions. They sent three Hieronymite monks to govern the islands. Las Casas helped choose them and write their instructions. Las Casas himself was given the official title of "Protector of the Indians". His job was to advise the governors on Native American issues, speak for them in court, and send reports to Spain.

However, the Hieronymite monks found it hard to make big changes because all the colonists were against it. They did try to gather Native Americans into towns, as Las Casas wanted. But Las Casas was disappointed and felt they weren't doing enough. He became very unpopular with the Spanish settlers and had to seek safety in a Dominican monastery. In 1517, he returned to Spain to report that the reforms had failed.

A New Plan for Colonization

Back in Spain, Las Casas met the young King Charles I. He gained the support of the king's advisors. Las Casas suggested a new plan: end the encomienda system and gather Native Americans into self-governing towns. These towns would pay tribute directly to the king. He still thought African slaves could replace Native American labor.

He also proposed a new kind of colonization. Spanish peasants would move to the Americas to farm small plots of land. This way, colonization wouldn't rely on using up resources or forced Native American labor. Las Casas tried to recruit many peasants, but it was difficult. Fewer families went than planned, and they faced many challenges. Las Casas was very upset by this failure. He decided to try a personal project instead.

He asked for land in Venezuela to start a peaceful settlement at Cumaná. There were already some monks there, but Spanish slave traders from a nearby island were bothering them. Las Casas wanted to protect the Native Americans and start a system of trade. He had to fight a long legal battle to get the land.

In 1520, he finally got the land, but it was smaller than he wanted. He couldn't extract gold or pearls, which made it hard to find investors. He left in November 1520 with only a small group of peasants. When he arrived in Puerto Rico in 1521, he heard bad news. Native Americans had attacked a monastery in the area he wanted to colonize because of slave raids. The peasants he brought left him. Las Casas went to his colony, which was already damaged. He worked there for months, constantly bothered by Spanish pearl fishers who traded slaves for alcohol. In early 1522, he left to complain to the authorities. While he was gone, the native Caribs attacked the settlement, burning it and killing four of his men. This event was used by his enemies to argue that Native Americans needed to be controlled by force.

Becoming a Friar and Missionary

After these failures, Las Casas joined the Dominican monastery of Santa Cruz in Santo Domingo in 1522 and became a Dominican friar in 1523. He continued his studies there. He helped build a monastery in Puerto Plata and became its leader. In 1527, he began writing his History of the Indies, which described what he had seen during the conquest.

In 1531, he wrote a letter protesting the mistreatment of Native Americans again. In 1533, he helped create a peace treaty between the Spanish and a rebel Native American chief named Enriquillo. In 1534, Las Casas tried to go to Peru to see the early stages of the conquest of the Inca Empire. He made it to Panama but had to turn back. In Nicaragua, he argued with the Governor, Rodrigo de Contreras, because Las Casas strongly opposed the Governor's slave expeditions.

In 1536, Las Casas went to Guatemala with other friars to start a mission among the Maya Indians. They studied the Kʼicheʼ language and then went into a region called Tuzulutlan, known as "The Land of War."

Also in 1536, Las Casas went to Oaxaca, Mexico, to debate with Franciscan friars. The Franciscans used a method of mass conversion, baptizing thousands of Native Americans quickly. Las Casas argued that conversions without proper understanding were not valid. He wrote a book called "De unico vocationis modo" (On the Only Way of Conversion) about his missionary ideas. As a result of these debates, Pope Paul III issued a special order called "Sublimis Deus". This order stated that Native Americans were rational human beings and should be brought to the Christian faith peacefully.

Las Casas returned to Guatemala in 1537 to use his new method of conversion. His method had two main ideas: 1) preach the Gospel to everyone and treat them as equals, and 2) conversion must be voluntary and based on understanding. He chose a territory in Guatemala that the Spanish had not been able to conquer by military force. The governor agreed not to establish any new encomiendas there if Las Casas succeeded. Las Casas's friars set up churches and converted several native chiefs. The "Land of War" became known as "Verapaz", meaning "True Peace." In 1538, Las Casas was called to go to Mexico and then to Spain to find more Dominicans for the mission.

The New Laws and His Role as Bishop

In Spain, Las Casas worked to get official support for the Guatemalan mission. He got a royal order forbidding settlers from interfering in Verapaz for five years. He also told the theologians at Salamanca about the Franciscans' mass baptisms, which they condemned as wrong.

Las Casas also continued his fight against the mistreatment of Native Americans. The encomienda system had been abolished in 1523 but brought back in 1526. In 1542, Las Casas told Emperor Charles V about the terrible things happening in the Americas. He argued that the only solution was to remove Native Americans from the control of Spanish settlers. Instead, they should be directly under the Crown and pay tribute to the king.

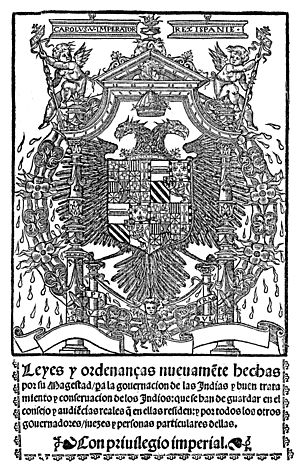

On November 20, 1542, the emperor signed the New Laws. These laws abolished the encomiendas and made it illegal to use Native Americans as slaves. They also planned to gradually end the encomienda system. However, these reforms were very unpopular in the Americas. Riots broke out, and people threatened Las Casas's life. The Viceroy of New Spain (Mexico), who was an encomendero himself, refused to put the laws into practice. Las Casas was also not fully happy with the laws, as they were not strong enough.

Before returning to the Americas, Las Casas was appointed Bishop of Chiapas. He took on this role in 1545. As a bishop, Las Casas often argued with the encomenderos and settlers in his area. He refused to forgive slave owners and encomenderos in confession unless they freed their slaves and returned their property. He even threatened to excommunicate (remove from the church) anyone who mistreated Native Americans.

The New Laws were finally canceled on October 20, 1545. More riots broke out against Las Casas. After a year, he was so unpopular that he had to leave his diocese. He went to a meeting of bishops in Mexico City in 1546 and never returned to Chiapas. His last act as Bishop was to write a guide for confession, still refusing to forgive unrepentant encomenderos. He left for Europe in December 1546.

Debating for Justice: The Valladolid Debate

When Las Casas returned to Spain, he faced many accusations. Some people said his rules for confession meant he was denying the Spanish king's right to rule the colonies, which was like treason. The Crown even ordered copies of Las Casas's confession guide to be burned. Las Casas defended himself by arguing that the only legal way for Spain to claim lands in the Americas was through peaceful teaching of Christianity. He said all warfare against native peoples was illegal and unjust.

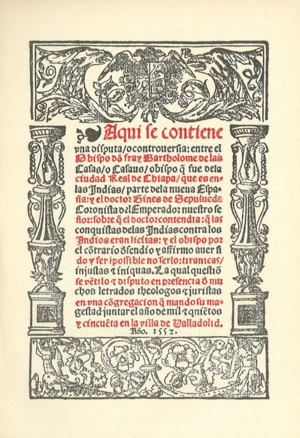

To settle these arguments, a famous debate was held in Valladolid in 1550–51. This was the Valladolid debate. Las Casas debated against Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, a scholar who argued that some native peoples were not capable of ruling themselves and needed to be controlled by force. Sepúlveda believed they should be made Christian, which required them to be "pacified" (controlled).

Las Casas argued that the Bible did not support war against all non-Christians. He said that Native Americans were civilized and had their own social order. He insisted that peaceful missions were the only true way to convert them. He also said that it was better for some weak Native Americans to suffer from stronger ones than for all Native Americans to suffer under the Spanish. The debate ended without a clear winner, but both sides claimed victory.

His Important Writings

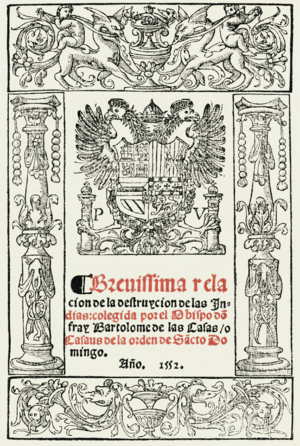

A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies

This book was written in 1542 and published in 1552. It describes the mistreatment of Native Americans during the early years of Spanish colonization. Las Casas wrote it because he feared Spain would face punishment from God. He wanted to show the unfair treatment of the native people, especially on the island of Hispaniola. His book helped lead to the New Laws of 1542 and the Valladolid debate.

The book became a key part of the "Black Legend". This was a way of describing the Spanish Empire as very cruel and violent. The book was republished many times in countries that were against Spain for political or religious reasons.

Apologetic History of the Indies

This book describes the cultures of the native peoples of the Americas, like the Taíno. Las Casas wrote it to defend the cultural level of Native Americans. He argued that they were just as civilized as ancient civilizations like the Romans, Greeks, and Egyptians. He even said they were more civilized than some European cultures.

He wrote: "All people of these our Indies are human... they had their republics, places, towns, and cities most abundant and well provided for, and did not lack anything to live politically and socially, and attain and enjoy civil happiness.... And they equaled many nations of this world that are renowned and considered civilized, and they surpassed many others, and to none were they inferior." This work is seen as an early example of anthropology, the study of human societies and cultures.

History of the Indies

Las Casas started writing this three-volume work in 1527 and finished it in 1561. It covers the history of the Americas from Christopher Columbus's arrival in 1492 to 1520. Much of it is based on what Las Casas saw himself. In this book, Las Casas finally expressed regret for supporting African slavery. He wrote a sincere apology, saying he realized that black slavery was just as wrong as Native American slavery. This book was not published until 1875, more than 300 years after he wrote it.

Bartolomé de las Casas's Legacy

Bartolomé de las Casas's legacy has been debated a lot. After he died, his ideas were often seen as too extreme in Spain. His enemies' writings were widely read. As other European powers grew stronger, they used Las Casas's accounts to criticize the Spanish Empire. This is sometimes called the "Black Legend".

Some Spanish historians in the late 1800s and early 1900s tried to create a "White Legend". They argued that the Spanish Empire was good and just, denying any negative effects of colonization. They called Las Casas a "paranoic" and a traitor.

Why Some People Criticized Him

Las Casas has been criticized for exaggerating the terrible things he described. Some scholars say his initial population numbers for Native Americans were too high. They also argue that European diseases were the main cause of population decline, not violence. However, modern historians agree that the population decline was huge (80-90%) and was caused by many factors related to the arrival of Europeans, especially disease. Historians also note that exaggeration was common in writings from the 1500s. Even Las Casas's enemies reported many gruesome acts against Native Americans. Most historians today believe Las Casas's general description of a violent and abusive conquest was accurate.

One common criticism is that Las Casas suggested replacing Native American slaves with African slaves. Even though he later regretted this and apologized in his History of the Indies, some people blame him for the start of the transatlantic slave trade. Other historians argue that the slave trade was already happening before he wrote about it.

Some recent scholars argue that Las Casas was more of a politician than just a humanitarian. They say his policies to free Native Americans were also linked to ways to get resources from them more efficiently. They also suggest he didn't realize that replacing native religions with Christianity was also a form of colonialism. However, others disagree, saying this view is too modern for the time he lived in.

Cultural Legacy

In 1848, the capital of the Mexican state of Chiapas was renamed San Cristóbal de Las Casas in his honor. His work inspires groups like the Las Casas Institute at Blackfriars Hall, Oxford. He is also seen as an early thinker behind the liberation theology movement.

Bartolomé de las Casas is remembered in the Church of England on July 20 and in the Evangelical Lutheran Church on July 17. The Catholic Church began the process for his beatification (a step towards sainthood) in 2002.

He was one of the first to believe in the unity of all humankind, stating that "All people of the world are humans." He believed everyone had a natural right to liberty. A human rights institute in San Cristóbal de las Casas, the Centro Fray Bartolomé de las Casas de Derechos Humanos, was founded in his name in 1989.

Residencial Las Casas in Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico, is named after him. He is also featured on the one-cent coin of the Guatemalan quetzal. The small town of Lascassas, Tennessee, in the United States, is also named after him.

Images for kids

-

A contemporary painting of King Ferdinand "The Catholic"

See also

In Spanish: Bartolomé de las Casas para niños

In Spanish: Bartolomé de las Casas para niños

- Fountain to Bartolomé de las Casas

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |