Madrid Codex (Maya) facts for kids

The Madrid Codex is an ancient book made by the Maya people long ago. It's also called the Tro-Cortesianus Codex. This book is one of only four known Maya books that survived from before the Spanish arrived in the Americas (around 900–1521 AD). The Madrid Codex is kept at the Museo de América in Madrid, Spain. It's considered a very important item in their collection.

Because the original book is very old and fragile, a perfect copy is shown instead. For a while, this codex was split into two separate pieces. People called them the "Codex Troano" and the "Codex Cortesianus." In the 1880s, a smart researcher named Leon de Rosny figured out that these two pieces actually belonged together. He helped put them back into one book. After that, the combined book was brought to Madrid and became known as the "Madrid Codex," which is its most common name today.

Contents

What it Looks Like

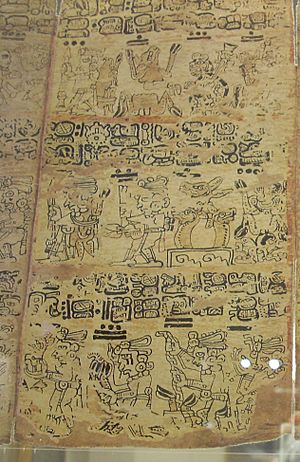

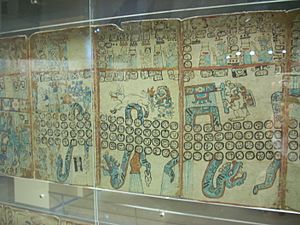

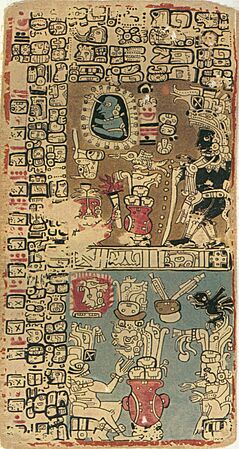

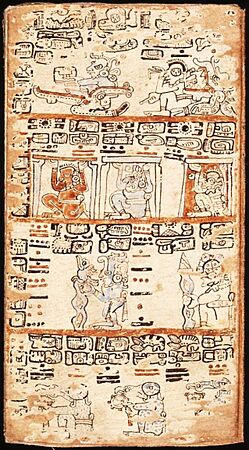

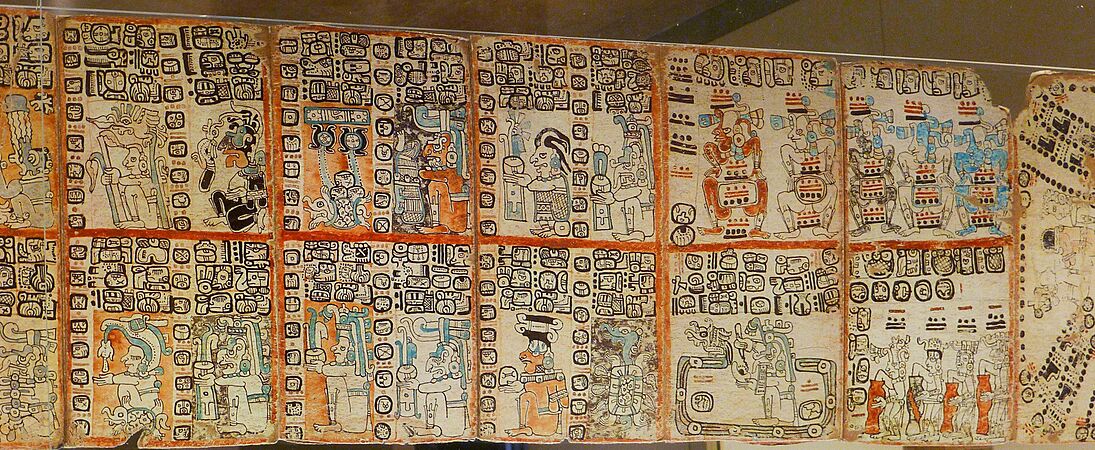

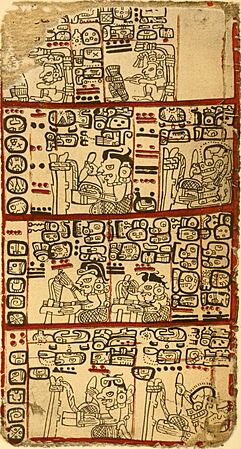

The Madrid Codex was made from a long strip of special paper called amate. This paper was folded up like an accordion. Then, it was covered with a thin layer of smooth stucco, which was used as the surface for painting.

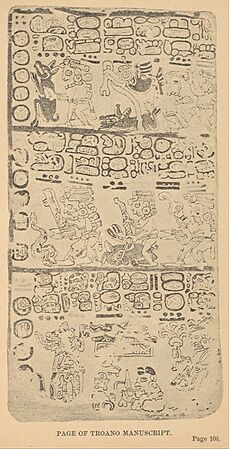

The complete book has 56 sheets. Both sides of each sheet were painted, making a total of 112 pages. The larger part, called the Troano, has 70 pages. The other 42 pages were known as the Cortesianus Codex. Each page is about 23.2 by 12.2 centimetres (9.1 by 4.8 in) in size.

What's Inside the Codex

The Madrid Codex is the longest of the Maya books that still exist. It mostly contains special calendars and predictions. These were used by Maya priests to help them with their ceremonies and to tell the future. The codex also has some information about stars and planets, but not as much as other Maya books. Some parts of the codex might have been copied from even older Maya writings. The book also describes a special New Year ceremony.

Many experts believe that several different scribes, maybe as many as eight or nine, worked on this book. They likely wrote different sections of the manuscript. Because the book is about religious topics, it's thought that the scribes themselves were priests. The codex was probably passed down from one priest to another, with each new owner adding their own part to the book.

The pictures in the Madrid Codex show various rituals, like those for bringing rain. They also show everyday activities such as beekeeping, hunting, fighting, and weaving. Other images show Maya gods smoking sikar, which were like early versions of cigars made from tobacco leaves.

Where it Came From

Most experts believe the Madrid Codex was made before the Spanish arrived. It was probably created in the Yucatán region. The language used in the book is a type of Mayan language called Yucatecan. This language was spoken in areas like Yucatán, Chiapas, Belize, and Guatemala.

One scholar, J. Eric Thompson, thought the Madrid Codex came from western Yucatán and was made between 1250 and 1450 AD. Other experts think it might have come from the Petén region in Guatemala. Some scholars also noticed that the style of the codex looks similar to paintings found at ancient Maya cities like Chichen Itza, Mayapan, and other sites along the east coast.

How it Was Found

The codex was discovered in Spain in the 1860s. It was found in two separate pieces in different places. This is why it's also called the Tro-Cortesianus Codex, named after its two parts.

A researcher named Léon de Rosny realized that both fragments were part of the same book. The larger piece, the Troano Codex, was found by a French scholar named Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg in 1866. He found it with a man named Juan de Tro y Ortolano in Madrid. Brasseur de Bourbourg was the first to identify it as a Maya book. The Troano Codex later went to the National Archaeological Museum of Spain in 1888.

The smaller piece, the Cortesianus Codex, was offered for sale by a Madrid resident in 1867. The National Archaeological Museum bought it in 1872 from a book collector. This collector claimed he had bought the codex in Extremadura, a region in Spain. Many Spanish explorers and conquerors, including Hernán Cortés, came from Extremadura. It's possible that one of these explorers brought the codex to Spain. The museum director named the Cortesianus Codex after Hernán Cortés, thinking he might have brought it to Spain himself.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Códice Tro-Cortesiano para niños

In Spanish: Códice Tro-Cortesiano para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |