J. Eric S. Thompson facts for kids

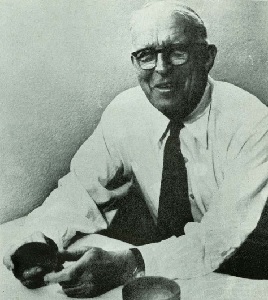

Sir John Eric Sidney Thompson (born December 31, 1898 – died September 9, 1975) was a very important English archaeologist, ethnohistorian, and epigrapher who studied ancient Mesoamerica. He was a leading expert in Maya studies, especially in understanding the Maya script, and his work was highly influential until the 1960s.

Contents

About Eric Thompson

His Early Life

Eric Thompson was born in London, England, on December 31, 1898. His father, George Thompson, was a famous surgeon. Eric went to Winchester College for his education when he was 14 years old.

In 1915, during World War I, Thompson was too young to join the army, but he used a different name, "Neil Winslow," to sign up. He was wounded a year later and sent home to recover. He continued to serve in the Coldstream Guards until the war ended.

After the war, Thompson went to Argentina to work on a family cattle farm as a gaucho (a cowboy). When he came back to England in the early 1920s, he wrote his first article about his experiences there.

His Education

Thompson first thought about becoming a doctor or working in politics. But then he decided to study anthropology at Fitzwilliam House, Cambridge. He studied with a famous professor named A.C. Haddon.

After finishing his degree in 1925, Thompson wrote to Sylvanus G. Morley, who was in charge of a big project at Chichen Itza for the Carnegie Institution for Science. Thompson asked for a job in the field. Morley hired him, probably because Thompson had already taught himself to read Maya hieroglyphic dates, which was a very valuable skill.

Starting His Career

In 1926, Thompson arrived in the Yucatan region of Mexico to work at Chichen Itza. He started by working on the carvings (called friezes) at the Temple of the Warriors. He later described this work as "a sort of giant jigsaw puzzle."

Later that year, Morley sent Thompson to explore the ancient site of Coba. During his first time there, Thompson was able to figure out the dates on the Macanxoc stela (a carved stone monument). At first, Morley, who was a top expert, didn't agree with Thompson's readings. But after another trip to Coba, Morley saw that Thompson was right. This was a big moment for Thompson, showing he was a rising star in understanding Maya writing.

Within the next year, Thompson became the Assistant Curator at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. He worked there until 1935, when he moved to a job at the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D.C.

In 1926, Thompson also joined an expedition to Lubaantun in British Honduras (now Belize). This fieldwork led him to disagree with another archaeologist's ideas about how ancient buildings were constructed.

Working in the Field

Near the end of his first time at Lubaantun, another site called Pusilha was found. Thompson was sent to explore it with his guide, Faustino Bol, who was a Mopan Maya. Thompson learned a lot from talking with Faustino about the ancient Maya and their culture. He realized that "archaeological excavations were not the only means of learning about the ancient ways." This led him to write his first book, Ethnology of the Mayas of Southern and Central British Honduras (1930). This book used information from living Maya people and historical records to help understand ancient Maya archaeology and writing.

In 1931, Thompson and Thomas Gann wrote a book together called The History of the Maya from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Thompson also started a new project at the site of San Jose in Belize. Here, he studied an "average" Maya city. His research helped create a timeline of pottery styles from the early Preclassic Period to the end of the Classic Period. This report, published in 1939, was one of the first times "archaeological sciences" were used to study pottery changes over time.

Thompson was able to create pottery timelines at several sites, including Tzimin Kax, San Jose, and Xunantunich. These timelines helped archaeologists date sites that didn't have carved monuments with dates. His work helped show how different Maya sites in the lowlands developed culturally.

His Professional Work

During the 1940s, Thompson focused on trying to understand the Maya hieroglyphs that were not about dates. He published many papers on this topic. He also studied things like tattooing and tobacco use by the ancient Maya.

Thompson believed that ancient Maya society was very peaceful and led by priests who focused on religion and astronomy. He thought their cities were mainly ceremonial centers, not places where many people lived all the time. He also thought the Maya used a type of farming called slash-and-burn, which meant their population was spread out.

In 1943, Thompson wrote A Trial Survey of the Southern Maya Area, describing sites like Kaminaljuyui and Copan. He suggested that the Maya were peaceful because their cities didn't seem to have strong defenses. He also talked about the decline of Maya art and architecture, which he called "Balkanization," meaning a time of political breakdown. He also believed that the Aztecs, a more warlike group, were involved in the downfall of the Maya priest-rulers.

Thompson was a very productive writer. He published many textbooks and articles. In 1945, he wrote about how archaeologists should use a historical approach in their studies. He also identified different periods in Maya development: the formative period, the Initial Series, transition period, Mexican period, and Mexican absorption period. These ideas helped shape the field for many years.

He thought the formative period began before A.D. 325, with simple pottery and large pyramids. The Initial Series period (Classic phase) he divided into two parts, with different pottery and carved monuments. He believed the Transition period (900 A.D. to 987) saw the fall of Chichen Itza and growing Mexican influences. The Mexican period, for him, marked a decline in Maya civilization due to conflicts, with less hieroglyphic writing and more worship of Mexican gods. He thought the Mexican Absorption Period (1204 A.D. to 1540) saw most major cities abandoned and little new art.

While Thompson made huge contributions, some of his ideas have been updated or changed by newer research. For example, he thought the Maya used sails for water travel, but later research suggests they mostly used canoes. He also combined several Maya gods into one, like the Moon Goddess Ix Chel, based on old, possibly mistranslated Spanish texts. Modern research shows that the Maya had a more complex social structure than Thompson thought, with a middle class, not just two main groups of priests and farmers.

Thompson knew that estimating ancient populations was hard. He wrote about factors that could make population estimates wrong, like how the ancient Maya might abandon a hut after someone died there. He also noted that the Maya often moved from place to place to find resources.

One of Thompson's most important works was Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: Introduction. He made big steps in understanding Maya hieroglyphs, especially the calendar and astronomy. He also created a numbering system for the glyphs (the T-number system) that is still used today. However, he strongly believed that Maya writing was based on ideas (ideographic) rather than sounds (phonetic). He disagreed with the Russian linguist Yuri Knorozov, who said that the glyphs had phonetic parts. Thompson's strong criticism made many other scholars ignore Knorozov's work for a long time.

Thompson also wrote about the challenges of understanding Maya writing, especially the notes from Diego de Landa, a Spanish bishop. He warned that Landa's information might not be completely accurate. However, it was later proven that Knorozov's ideas about the Maya language being both phonetic and ideographic were correct.

Thompson believed that Maya inscriptions were only about religion and astronomy, with no history or politics. But in the early 1960s, the work of Tatiana Proskouriakoff on the carvings at Piedras Negras showed that his view was "completely mistaken." This new research proved that Maya texts did record historical events and the lives of rulers.

Thompson continued to work on Maya writing and history until the end of his career. He was one of the last "generalists," meaning he did many different things, from finding new sites and digging them up to studying Maya pottery, art, and writing. He also wrote books for the general public, like Rise and Fall of the Maya Civilization (1954) and Maya Hieroglyphs without Tears (1972), to share his knowledge of the Maya with everyone.

Later Life and Honors

Eric Thompson received four honorary doctorates from universities in three different countries. He was also given special awards by Spain (the Order of Isabel la Catolica), Mexico (the Aztec Eagle) in 1965, and Guatemala (the Order of the Quetzal) during his last trip to the Maya lands in 1975.

In 1975, just after his 76th birthday, Queen Elizabeth II knighted Thompson. This made him the first archaeologist of the New World to receive such a high honor. He passed away nine months later, on September 9, 1975, in Cambridge, England, and was buried in Ashdon, Essex.

See also

In Spanish: Eric S. Thompson para niños

In Spanish: Eric S. Thompson para niños

- Madrid Codex (Maya)

- Yuri Knorozov

- Tatiana Proskouriakoff

- Maya civilisation

- Chichen Itza

- David Stuart (Mayanist)

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |