Yuri Knorozov facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Yuri Knorozov

|

|

|---|---|

| Юрий Кнорозов | |

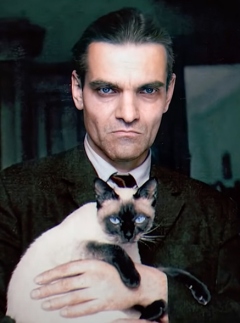

Knorozov with his Siamese cat Asya in the 1980s

|

|

| Born |

Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov

19 November 1922 Yuzhny, Kharkov Governorate, Ukrainian SSR

|

| Died | 31 March 1999 (aged 76) Saint Petersburg, Russia

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Education | Moscow State University |

| Known for | Decipherment of Maya script |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | N.N. Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Ethnography and Anthropology |

| Influenced | Galina Ershova |

Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov (Russian: Ю́рий Валенти́нович Кноро́зов; 19 November 1922 – 31 March 1999) was a smart linguist and epigrapher from the Soviet Union and Russia. He is famous for helping to figure out the Maya script. This was the special writing system used by the ancient Maya civilization in Mesoamerica long ago. Knorozov showed that Maya writing used syllabic signs, which was a huge step in finally reading the mysterious script.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Yuri Knorozov was born in a village called Yuzhny, near Kharkov, which was then in the Ukrainian SSR. His parents were educated Russians. His grandmother, Maria Sakhavyan, was a famous actress in Armenia.

As a child, Yuri was very smart and curious. He was good at playing the violin, writing poetry, and drawing. He got excellent grades in most subjects, except for Ukrainian. At age 5, he had a bad head injury that almost made him blind. Even though he was bright, he sometimes struggled in school and was a bit stubborn.

In 1940, when he was 17, Knorozov moved to Moscow. He began studying ethnology at Moscow State University. He first focused on Egyptology, which is the study of ancient Egypt.

World War II and a Famous Story

World War II started in 1941, interrupting Knorozov's studies. Because of his health, he couldn't join the regular army. He spent some years in German-occupied areas, avoiding being forced to join the German army by moving from village to village and working as a teacher. In 1943, he got very sick with typhus but survived. He then escaped to Moscow and continued his studies. Later, he worked as a telephone operator in an army unit near Moscow.

There's a popular story about Knorozov during the war. It says that when the Soviet army entered Berlin, Knorozov found a special book. This book supposedly sparked his interest in the Maya script. The story claims he found the Berlin State Library on fire and rescued a rare book. This book had copies of the three known Maya codices (ancient Maya books). He supposedly took this book back to Moscow, and it became the basis for his research.

However, Knorozov's student, Galina Ershova, couldn't find proof he left the Moscow area during 1943–1945. Knorozov himself denied the story in an interview before he died. He said it was a misunderstanding. He explained that books were found in boxes, packed by the Germans, and then sent to Moscow. There was no fire.

Returning to His Studies

After World War II ended in 1945, Knorozov went back to Moscow State University. He finished his studies in ethnography. He continued his research on ancient Egypt and also studied other cultures, like China. He was very interested in old languages and writing systems, especially Egyptian hieroglyphs. He also read medieval Japanese and Arabic literature. His roommate said Knorozov was completely dedicated to science, spending all his scholarship money on books.

While still a student, Knorozov started working at the Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography (IEA), part of the Russian Academy of Sciences. His later discoveries were published by the IEA.

As part of his studies, Knorozov spent several months on a trip to Central Asian Soviet republics. He studied how Russian expansion affected nomadic groups there. At this time, he wasn't yet focused on the Maya script.

This changed in 1947. His professor encouraged him to write his main paper on the "de Landa alphabet". This was a record made by a Spanish bishop named Diego de Landa in the 1500s. De Landa claimed he had written down the Spanish alphabet using Maya hieroglyphs. De Landa had destroyed many Maya books, and he made this "alphabet" to explain his actions. The original document was lost, but a copy was found in the 1860s.

Earlier attempts to use de Landa's "alphabet" to read Maya writing had failed. This was because it seemed confusing, with different symbols for the same letters.

Knorozov's Big Discovery

In 1952, Knorozov, then 30 years old, published an important paper called "Ancient Writing of Central America." In this paper, he suggested that many ancient scripts, like Egyptian hieroglyphs and Cuneiform script, were not just pictures representing whole words. Instead, they also had many phonetic parts. This means some symbols represented sounds, like letters in an alphabet or parts of words in a syllabary. This was already known for Egyptian hieroglyphs, but most experts thought Maya writing was different. Knorozov believed Maya writing should be similar to others, and that no writing system was purely made of pictures.

Knorozov's key idea was to see de Landa's "alphabet" not as an alphabet, but as a syllabary. He thought that when de Landa asked a Maya scribe to write the Spanish letter "b," the scribe actually wrote the Maya symbol for the sound /be/. Knorozov didn't translate many new words himself, but he showed that this approach was the way to understand the script. De Landa's "alphabet" became almost like the "Rosetta Stone" for Maya decipherment.

Another important idea from Knorozov was called synharmony. This meant that Maya words or syllables with a consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) pattern were often written with two symbols, each representing a consonant-vowel (CV) sound. The second vowel was ignored when reading. Also, the vowel of the second symbol would match the vowel of the first symbol. Later studies proved this idea was mostly correct.

How His Work Was Received

When Knorozov's paper was published, it faced strong criticism. J. Eric S. Thompson, a leading British expert on the Maya at the time, was a main critic. Thompson believed Maya writing was based on pictures and didn't record actual history. His view was very popular, and many other scholars agreed with him.

According to Michael Coe, a famous scholar, "during Thompson's lifetime, it was a rare Maya scholar who dared to contradict" him. Because of this, it took much longer to read Maya scripts than Egyptian or Hittite ones. Real progress only happened after Thompson passed away in 1975.

The situation was also complicated by the Cold War. Some people dismissed Knorozov's work because it came from the Soviet Union. His paper even had a foreword (introduction) written by the editor that praised the Soviet approach. However, Knorozov himself never included such political comments in his own writings.

Progress in Deciphering Maya Script

Knorozov continued to improve his method. He published "The Writing of the Maya Indians" in 1963 and translations of Maya manuscripts in 1975.

In the 1960s, other Maya scholars started to build on Knorozov's ideas. They found more evidence that Maya inscriptions on stone monuments (called stelae) actually recorded their history, not just calendar or astronomy information. Tatiana Proskouriakoff, a Russian-born American scholar, was key in this. She eventually convinced Thompson and others that historical events were indeed written in the script.

Other early supporters of Knorozov's phonetic approach included Michael D. Coe and David H. Kelley. At first, they were a small group, but more and more scholars agreed as new evidence appeared.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Proskouriakoff and others kept developing the ideas. Using Knorozov's findings, they began to piece together parts of the script. A big breakthrough happened at a conference in Palenque in 1973. Using the syllabic approach, the scholars there were able to read a list of past rulers of that Maya city.

In the following decades, many more advances were made. Today, a large part of the surviving Maya inscriptions can be read. Most experts agree that Knorozov's ideas and insights were crucial. Professor Coe wrote that Yuri Knorozov, who was far from Western science and never saw a Maya ruin until the late 1980s, still "made possible the modern decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic writing."

Later Life and Legacy

Knorozov presented his work in 1956 at a conference in Copenhagen, but he couldn't travel abroad again for many years. In 1990, after relations between Guatemala and the Soviet Union improved, Guatemala's President invited Knorozov to visit. President Vinicio Cerezo gave Knorozov the Order of the Quetzal, a high honor. Knorozov visited several major Maya sites, including Tikal.

In 1994, the government of Mexico gave Knorozov the Order of the Aztec Eagle, their highest award for non-citizens. At the ceremony, he said in Spanish, Mi corazón siempre es mexicano (My heart always remains with Mexico).

Knorozov had many interests, including archaeology, semiotics (the study of signs and symbols), human migration to the Americas, and how the mind developed. But he is best remembered for his work on Maya studies.

In his final years, Knorozov suggested a place in the United States might be Chicomoztoc. This is a legendary ancestral land from which some indigenous peoples in Mexico are said to have come.

Yuri Knorozov died in Saint Petersburg on March 31, 1999, from pneumonia. He was survived by his daughter Ekaterina and granddaughter Anna.

Images for kids

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |