Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg

|

|

|---|---|

Abbé Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg. Lithograph from J. Windsor's 19th-century publication, Aboriginal America.

|

|

| Born | September 8, 1814 Bourbourg, France |

| Died | January 8, 1874 (aged 59) Nice, France |

| Occupation | Catholic priest; writer, ethnographer, historian and archaeologist. |

| Subject | Mesoamerican studies |

Abbé Charles-Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg (born September 8, 1814 – died January 8, 1874) was a French writer, historian, and Catholic priest. He became an expert in Mesoamerican studies, traveling a lot in that region.

His writings and discoveries of old documents greatly helped us understand the languages, writing, history, and culture of the Maya and Aztec people. However, he also had some interesting ideas. He thought the ancient Maya might be connected to the lost continent of Atlantis. These ideas later inspired others and led to some unproven theories about the Maya.

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Charles-Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg was born in Bourbourg, a small town in France. This was at the end of the First French Empire.

When he was young, he went to Ghent, Belgium, to study religion and philosophy. He became very interested in writing during his studies. He wrote essays about local stories and history, which helped him meet other writers. In 1837, when he was 23, Brasseur moved to Paris. He started writing for political newspapers and journals. He also wrote several historical stories and novels. Some of his novels were similar to other popular books of the time. Sometimes, people said his works were too much like others, or not always accurate.

Despite these comments, he became known as a talented young writer. He later moved to Rome to continue his studies. In 1845, at age 30, he became a Roman Catholic priest.

Journey to Quebec

In 1844, a Canadian priest named Abbé Léon Gingras met Brasseur in Rome. Gingras was very impressed and wanted Brasseur to work at a seminary in Quebec, Canada. He wrote to his friends in Quebec, saying they should try hard to get Brasseur to come.

So, in the autumn of 1845, after becoming a priest, Brasseur left Europe for Canada. He stopped briefly in Boston first.

When he arrived in Quebec City, he started teaching church history at the Séminaire de Québec. But after a short time, his lectures stopped for unknown reasons.

With more free time, Brasseur began researching the history of Quebec. He focused on François de Laval, the first Catholic Bishop of Quebec. Brasseur published a book about Laval in 1846. However, his Canadian colleagues were not happy with what he wrote. This made his position in Quebec difficult. He also found the harsh winter climate very unpleasant. These reasons likely led to his departure.

He left the seminary later that year and returned to Boston. There, he found a job with the Catholic diocese and became a vicar-general.

Towards the end of the year, Brasseur went back to Europe. He spent time researching in archives in Rome and Madrid. He was preparing for a new adventure: traveling to Central America.

Exploring Central America

From 1848 to 1863, Brasseur traveled widely as a missionary in Mexico and Central America.

During these trips, he paid close attention to ancient sites and objects. He learned a lot about the history of the region and the Pre-Columbian civilizations. These ancient cities and monuments were still there but not well understood.

Using information he gathered and from other scholars, he published a history of the Aztec civilization between 1857 and 1859. This book included everything known about the Aztec kingdom, which had been conquered by the Spanish about 300 years earlier.

He also studied local languages and how to write them using the Latin alphabet. From 1861 to 1864, he published a collection of documents written in these native languages.

In 1864, he worked as an archaeologist for the French military in Mexico. His work, Monuments anciens du Mexique, was published by the French government in 1866.

Finding de Landa's Important Work

In 1862, Brasseur de Bourbourg was looking through old documents in Madrid, Spain. He found a copy of a manuscript written by a Spanish priest named Diego de Landa around 1566. De Landa had lived among the Maya peoples in Central America after the Spanish conquest. He had written down much information about Maya people and their customs.

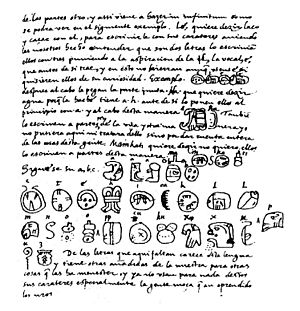

Brasseur was most interested in a part where de Landa showed what he called "an alphabet" of the Maya writing system. This system used Maya hieroglyphics, which no one could read at the time. De Landa had written down Maya symbols that supposedly matched Spanish letters, as told to him by a Maya person. Brasseur realized this could be a key to understanding the Maya script. He announced his discovery when he published the manuscript in 1863.

However, when Brasseur and others first tried to use this "de Landa alphabet" to read the Maya symbols, it didn't work well. The alphabet seemed inconsistent. But much later, this document and de Landa's alphabet became very important. Scholars realized the Maya signs were mostly syllables (like parts of words), not single letters. This understanding finally led to the successful reading of Maya writing.

Publishing the Popol Vuh

In 1861, Brasseur published another important work. It was a French translation of the Popol Vuh, a sacred book of the Quiché (Kʼicheʼ) Maya people. He also included a grammar of the Kʼicheʼ language and an essay on Maya stories and beliefs.

Ideas About Atlantis

Brasseur began to write about Atlantis in his book Grammaire de la langue quichée (1862). He believed that the lost land described by Plato had existed. He thought it was a very advanced civilization before Europe and Asia had their own. He even suggested that some European words might come from ancient American languages. He thought the old cultures of the New World and Old World were always in touch.

In 1866, a book called Monuments anciens du Mexique was published. It had text by Brasseur and beautiful pictures by Jean-Frédéric Waldeck. Waldeck's drawings of the ruins at Palenque were based on what he saw. But his artistic ideas made it seem like Maya art was very similar to ancient Greek and Roman art. This idea was later proven wrong. However, Waldeck's art made people wonder if there was a connection between the New World and Old World civilizations, perhaps through the lost continent of Atlantis.

Brasseur de Bourbourg strengthened these ideas in his book Quatre Lettres sur le Méxique (1868). He made many comparisons between Maya and Egyptian gods and beliefs. He suggested they all came from a common source on Atlantis. He further developed these ideas, presenting a history of Atlantis based on his understanding of Maya stories. His writings inspired other people, like Ignatius L. Donnelly, whose book Atlantis: The Antediluvian World mentioned Brasseur's work many times. However, other scholars at the time did not agree with Brasseur's theories about Atlantis.

Brasseur's interest in spiritual ideas and his theories about the Maya and Atlantis helped create a field of study called Mayanism, which sometimes includes unproven ideas.

Finding a Maya Codex

In 1866, Brasseur de Bourbourg saw an old book in Madrid. It belonged to a professor named Juan de Tro y Ortolano. This book was a codex, made from tree bark, folded like a screen with many pages. Brasseur quickly recognized the signs and drawings as Mayan. He had seen similar markings during his travels in Central America.

Tro y Ortolano allowed him to publish the codex. Brasseur named it the Troano Codex in his honor. This discovery was very important because it was only the third Maya codex ever found. Brasseur knew how rare it was because de Landa, whose work he had found earlier, had ordered many such Maya books to be burned.

From 1869 to 1870, Brasseur published his analysis of the Troano codex. He tried to translate some of the symbols, using the pictures and de Landa's alphabet. His attempts were not very successful.

However, his translation later inspired others to create unproven theories about a lost continent called Mu. Brasseur de Bourbourg was actually the first to use the name Mu.

A few years later, another Maya codex was found. It was called the Codex Cortesianus. Later, it was discovered that this was actually part of the Troano codex. The two parts were joined together and are now known as the Codex Madrid or Tro-Cortesianus. They are displayed in Madrid.

In 1871, Brasseur de Bourbourg published his Bibliothèque Mexico-Guatémalienne. This was a collection of writings and sources related to Mesoamerican studies.

His last article, "Chronologie historique des Mexicains" (1872), talked about the Codex Chimalpopoca. In it, he suggested four periods of major world disasters. He believed these started around 10,500 BC and were caused by shifts in the Earth's axis.

Death and Legacy

Charles-Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg died in Nice, France, in early 1874. He was 59 years old.

His work exploring ancient sites and his careful collection and publication of old documents were very helpful for later researchers. Even though many of his own theories and interpretations turned out to be incorrect, his efforts in finding and sharing these historical materials were very valuable.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg para niños

In Spanish: Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |