Ancient Maya art facts for kids

Ancient Maya art is the amazing artwork created by the Maya civilization. This culture lived in many small kingdoms in what is now Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras. Different art styles grew in different areas, often changing with the borders of Maya kingdoms.

Maya art began to really shine during the Classic Period (around 250 to 950 CE). Early Classic art (250-550 CE) was often more formal. Later Classic art (550-950 CE) became more expressive. The Maya also learned from other cultures. For example, the Olmec style influenced early Maya art. Later, the Teotihuacan style from central Mexico and the Toltec style also had an impact.

After the Classic Maya kingdoms declined, Maya art continued in the Postclassic Period (950-1550 CE), especially in the Yucatan peninsula. This period ended when European explorers arrived in the 1500s. After that, traditional art mostly survived in things like weaving, pottery, and house designs.

Contents

Learning About Maya Art

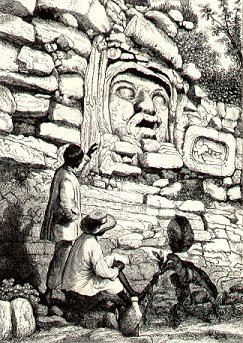

People started learning about Maya art in the 1800s. Explorers like John Lloyd Stephens and artists like Frederick Catherwood made drawings and took photos of Maya ruins. These helped people see the amazing monuments for the first time.

Later, in 1913, Herbert Spinden wrote an important book called A Study of Maya Art. This book helped set the stage for how we study Maya art today. It looked at common designs, like snakes and dragons.

In the 1950s, Tatiana Proskouriakoff helped us understand the timeline of Maya art better. Then, in the 1970s, new discoveries and studies really changed how we saw Maya art. Experts like Linda Schele and Mary Miller helped us understand the stories and history behind the art, especially about Maya kings and their lives.

Many new sculptures and pottery pieces were found over the years. This helped experts learn even more about the Maya spiritual world. Today, new studies continue to explore Maya art, looking at things like how pottery was made and how hieroglyphs are also works of art.

Amazing Maya Buildings

Maya towns and cities, especially the main centers where kings lived, were built with huge, flat stucco floors called plazas. These plazas were often on different levels, connected by wide, steep stairs. Tall temple pyramids stood above them. Over time, new layers were added to buildings, making them even bigger.

The Maya also built systems for water, like channels and drains. Outside the main centers, there were homes for less important nobles and smaller temples. Roads called sacbeob connected these centers to other living areas. The Maya cared a lot about how their buildings looked and where they faced.

Here are some types of stone buildings the Maya made:

- Ceremonial platforms: These were usually low platforms, less than 4 meters tall.

- Courtyards and palaces: Where royal families lived and held events.

- Other homes: Like a possible writers' house in Copan.

- Temples and temple pyramids: Pyramids often had tombs inside, with temples on top. The North Acropolis in Tikal has many burial temples.

- Ball courts: Where the Maya played a special ball game.

- Sweat baths: Like those found in Piedras Negras.

Some special groups of buildings include:

- Triadic pyramids: A large building with two smaller ones facing it, all on one platform.

- E-groups: A square platform with a pyramid on the west and a long building or three small ones on the east.

- Twin pyramid complexes: Two identical pyramids on opposite sides of a plaza, with other buildings nearby. These often marked important time periods.

In palaces and temples, the Maya often used a special type of arch called a 'corbelled vault'. This arch needed thick walls to support the high ceiling.

In northern Maya areas (like Campeche and Yucatan), buildings had their own unique styles. These styles, like Puuc, Chenes, and Rio Bec, used stone mosaics on their walls. They often featured stacked faces of the rain god and doorways shaped like serpent mouths. Uxmal is a famous Puuc site. Chichen Itza has both Classic and later Mexican-style buildings, like the round temple.

The Guatemalan Highlands also had building traditions. In the Postclassic period, sites like Q'umarkaj showed strong influences from the Toltec culture.

-

Chichen Itza, radial pyramid El Castillo, Postclassic

Sculptures in Stone

Before the Classic Period, the Izapa style was important. Many stone slabs (stelas) and altars were found there, showing stories and myths.

During the Classic Period, the Maya made many types of stone sculptures, usually from limestone:

- Stelas: These are tall, carved stone slabs, often with round altars. They usually show kings, sometimes dressed as gods. The faces on stelas are often realistic but don't always show individual features. Famous stelas are from Copan and Quirigua. Quirigua's stelas are especially tall, with one over 7 meters high!

- Lintels: These are carved stone beams placed above doorways. Yaxchilan is famous for its many lintels, which show kings meeting ancestors or gods.

- Panels and tablets: These were set into walls and platforms. Palenque has many beautiful examples, like the large tablets in the Cross Group temples. King Pakal's carved sarcophagus lid is also a unique masterpiece.

- Relief columns: Columns next to doorways in the Puuc region, decorated like stelas.

- Altars: Round or rectangular stones, sometimes with legs. They might have carvings of animals or symbols.

- Zoomorphs: Large boulders carved to look like supernatural creatures, covered with detailed carvings. These are mostly found in Quirigua.

- Ball court markers: Carved round stones placed in the middle of ball courts. They often show kings playing the ball game.

- Monumental stairs: Stairs with carved hieroglyphs or scenes. The giant hieroglyphic stairway at Copan is very famous. Some stairs show ball game scenes or even captives.

- Thrones and benches: Thrones had wide, square seats. Benches were longer and built into the architecture. Examples from Palenque and Copan show gods supporting them.

- Stone sculpture in the round: This means sculptures that are carved all around, not just on one side. Copan and Tonina are known for these, including statues of scribes and captive figures.

-

Yaxchilan lintel 24, king holding a torch and queen letting blood, 723–726 CE (British Museum)

-

Yaxchilan lintel, a war chief showing captives to the king, 783 CE (Kimbell Art Museum)

-

Relief column, Late Classic (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

One of twenty maize god sculptures from Copan temple 22, Late Classic (Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology)

-

Tonina monument 151, a tied prisoner, Classic

Wood Carvings

Many wood carvings likely existed, but most were destroyed by Spanish authorities in the 1500s. Only a few have survived. The most important Classic examples are carved lintels from the main Tikal pyramids. These 8th-century carvings show kings on their thrones with protector figures behind them, like a jaguar or a feathered serpent.

A rare everyday item is a small lidded box from Tortuguero with hieroglyphic writing. A free-standing wood sculpture from the 6th century shows a seated man, possibly holding a mirror.

Stucco Art and Decoration

Since ancient times, the Maya covered their floors and buildings with modeled and painted stucco plaster. This plaster often featured large masks of gods (like the sun, rain, and earth gods) in high relief. These masks are found on the sloped walls of temple platforms, like at Kohunlich.

Sometimes, entire buildings were covered in stucco, like Temple 16 in Copan, known as 'Rosalila'. This early temple, dedicated to the first king, Yax K'uk Mo', still has its plastered and painted walls. Stucco friezes (decorative bands), walls, and roof combs often had complex designs.

The Maya used different ways to decorate stucco surfaces. For example, the walls of the 'Temple of the Night Sun' in El Zotz have many slightly different god masks. A frieze from a Balamku palace showed four rulers sitting above the open mouths of different animals. Other friezes might focus on a single ruler on a symbolic mountain.

Friezes were often divided into sections. For instance, friezes from El Mirador show birds in the spaces of a wavy serpent's body. A palace wall in Acanceh has panels with different animal figures. A wall in Tonina shows continuous stories about human sacrifice.

Plastered roof combs usually had large images of rulers, often sitting on a symbolic mountain. The piers (supports) of the Palenque Palace are decorated with lords and ladies in special clothes. The entrance to the Acropolis (Str. 1) of Ek' Balam has detailed stucco figures.

Maya stucco art also includes realistic portraits, like the stucco heads of Palenque rulers and Tonina leaders. These portraits are very detailed, similar to Roman portraits. Some of these heads were part of life-size stucco figures on top of temples. Stucco glyphs (writing) were also created as part of larger texts.

-

Hormiguero, stucco head ("Maya Akhenaten"), Late Classic (Museo arqueológico Fuerte de S. Miguel, Campeche)

Colorful Wall Paintings

Because of the humid climate, not many Maya paintings have survived completely. However, important pieces have been found in many royal buildings, especially in hidden parts.

Mural paintings can show:

- Repeating designs, like flower symbols on walls in Palenque.

- Scenes of daily life, as in Calakmul.

- Ritual scenes with gods, like in the Post-Classic temples of Yucatán's east coast (Tulum). These later murals show influence from the 'Mixteca-Puebla style'.

Murals can also tell stories, often with hieroglyphic captions. The colorful Bonampak murals from 790 AD show amazing scenes of nobles, battles, and sacrifices. At San Bartolo, murals from 100 BCE tell myths about the Maya maize god and the hero twin Hunahpu. These paintings are very old but already show a developed style with soft colors.

Outside the Maya area, in Cacaxtla, Mexico, murals in a Maya style have been found. These include a fierce battle scene and Maya lords standing on serpents.

Wall paintings also appear on vault capstones (the top stones of arched ceilings), in tombs (like Río Azul), and in caves (like Naj Tunich). These are usually black on white, sometimes with red paint.

A special bright turquoise blue color, called 'Maya Blue', has lasted for centuries because of its unique chemical makeup. This color is found in Bonampak and other sites. The Maya used it until the 1500s, when the technique was lost.

Writing and Books

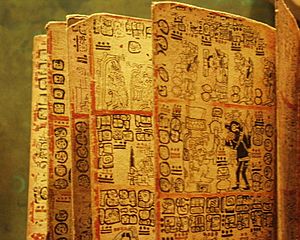

The Maya writing system uses about 1000 different characters, called hieroglyphs or 'glyphs'. It's a mix of signs for sounds and signs for whole words. This writing was used from the 3rd century BCE until after the Spanish arrived in the 1500s. We can read many of the characters today, but understanding all the texts is still a challenge.

Maya books were folded like an accordion. They were made from bark paper or leather covered with a smooth stucco layer for writing. They were protected by jaguar skin covers or wooden boards. Many books must have existed, as diviners (people who could predict the future) likely needed them.

Today, only three Maya hieroglyphic books from the Post-Classic period still exist: the Dresden, Paris, and Madrid codices. These books are mostly about predicting the future and religious rituals. They contain calendars, star charts, and prophecies. The Maya paid great attention to making the text and colorful pictures look beautiful together.

Besides the book glyphs, there was also a flowing, cursive writing style found in wall paintings and on pottery. Hieroglyphs themselves are very detailed and can be seen as art motifs. Sculptors sometimes even turned glyphs into small, lively scenes.

Amazing Maya Pottery

Most decorated Maya pottery (like cylinder vessels, lidded dishes, and vases) was used by Maya nobles. It was often given as gifts and passed down through families. These beautiful pieces were also buried with nobles in their graves. This tradition of gift-giving helped Maya artists create such high-quality pottery.

Maya pottery was made without a potter's wheel. It was carefully painted, carved, or scratched with designs. During the Early Classic period, some pottery was made using a fresco technique, where paint was applied to wet clay. Many workshops across the Maya kingdoms made these precious objects.

Vase decorations show many different things: palace scenes, court rituals, myths, and even texts about royal families. These scenes and texts help us understand Classic Maya life and beliefs. Pottery painted in black and red on a white background, looking like pages from lost books, is called 'Codex Style'.

Sculptural pottery includes lids of bowls with human or animal figures. Some of these black, shiny bowls are considered among the most beautiful Maya artworks.

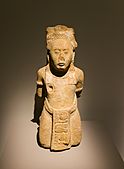

Ceramic sculptures also include incense burners and burial urns. The Classic burners from Palenque are well-known, with modeled faces of gods or kings. Large burial urns from Guatemala often feature a jaguar god. Post-Classic incense burners, especially from Mayapan, show standing gods or priests.

Finally, small figurines, often made from molds, are very lively and realistic. They show gods, animal-people, rulers, dwarfs, and scenes from daily life. Some of these figurines were also ocarinas (musical instruments) and might have been used in rituals. The most impressive ones come from Jaina Island.

-

Lidded basal flange bowl, El Peru, Guatemala, Early Classic (Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología de Guatemala)

Precious Stones and Other Carved Materials

It's amazing that the Maya, who didn't have metal tools, could carve hard materials like jade (jadeite). They made many royal items from jade, such as belt plaques, ear spools, pendants, and masks. Some flat, axe-shaped ornaments called celts were carved with images of kings. A famous example is the death mask of Palenque king Pakal, covered with jade pieces and eyes made of mother-of-pearl and obsidian. Another death mask, from a Palenque queen, was made of malachite. Many stone carvings also had jade inlays.

Other materials carved and engraved include flint, chert, shell, and bone. These were often found in special hidden spots or burials. 'eccentric flints' are ceremonial objects with unusual shapes, sometimes with multiple heads. Shells were carved into disks and other decorations showing human faces or gods. conch trumpets were also decorated. Human and animal bones were carved with symbols and scenes. A collection of small, carved bones from an 8th-century royal burial under Tikal Temple I shows some of the most detailed Maya engravings, including scenes with the Tonsured maize god in a canoe.

-

Flower-shaped jadeite earflares, Late Classic (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

-

Funerary mask of a Palenque queen covered with pieces of malachite, 7th century (site museum)

Clothing and Body Art

The Maya made textiles from cotton, but most haven't survived. However, Maya art shows us what they looked like. They made delicate fabrics for wrappings, curtains, and clothes. Daily clothing depended on a person's social status. Noblewomen usually wore long dresses, while noblemen wore loincloths, leaving their legs and upper bodies mostly bare unless they wore jackets or cloaks. Both men and women could wear turbans.

Costumes for ceremonies and festivals were very fancy and colorful. Animal headdresses were common. The king's formal clothes, shown on royal stelas, were the most elaborate, with many symbolic parts.

Wickerwork (things made from woven plant fibers) was probably very common, even though we only see it in art. The famous pop (mat) design shows how important it was.

Body decorations included painted patterns on the face and body. Some decorations were permanent, showing a person's status or age. These included shaping the skull, filing and decorating teeth, and tattooing the face.

Where to See Maya Art Today

Many museums around the world have Maya artifacts. The Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies lists over 250 museums with Maya collections!

In Mexico City, the Museo Nacional de Antropología has a huge collection of Maya art. Other important museums in Mexico include Museo Amparo in Puebla and the "Gran Museo del mundo maya" in Mérida.

In Guatemala, the Museo Popol Vuh and the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City have important collections.

In the United States, almost every major art museum has Maya artifacts. Some of the most important collections are at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. On the west coast, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) has a large collection of painted Maya pottery.

In Europe, the British Museum in London has famous Yaxchilan lintels. The Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin has a wide selection of Maya artifacts. The Museo de América in Madrid holds the Madrid Codex. Other notable European museums include the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris and the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde in Leiden, Netherlands.

Other Maya Arts

- Maya dance

- Maya dance drama

- Maya music

See also

In Spanish: Arte maya para niños

In Spanish: Arte maya para niños

- Ancient Maya graffiti

- Pre-Columbian art

- Painting in the Americas before Colonization

- Visual arts by indigenous peoples of the Americas

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |