Kimbell Art Museum facts for kids

The south wing of the museum showing a portico and five vaulted galleries. The tree-lined entry courtyard is at the far left.

|

|

| Established | 1972 |

|---|---|

| Location | Fort Worth, Texas, USA |

| Type | Art museum |

| Collections | European Old Masters |

| Collection size | 350 |

| Nearest car park | On site (no charge) |

The Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, is a famous place that has a wonderful collection of art. It also hosts special art shows, offers learning programs, and has a big library for people who want to study art. The first artworks came from the private collection of Kay and Velma Kimbell. They also gave money to build the museum.

The museum building was designed by a famous architect named Louis I. Kahn. Many people think it is one of the most important buildings built in recent times. It is especially known for the beautiful, soft, silvery natural light that shines across its curved gallery ceilings.

Contents

History of the Kimbell Art Museum

Kay Kimbell was a rich businessman from Fort Worth. He owned more than 70 companies. His wife, Velma Fuller, helped him become interested in collecting art. In 1931, she took him to an art show where he bought a British painting. In 1935, they started the Kimbell Art Foundation to create an art institute. By the time Kay died in 1964, they had collected what was considered the best group of old masters paintings in the Southwest. Kay left most of his money to the Kimbell Art Foundation. Velma also gave her share of their money to the foundation. She gave a very important instruction: to "build a museum of the first class."

The foundation's board of trustees hired Richard Fargo Brown. He was the director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art at the time. Brown became the first director of the Kimbell Art Museum. His job was to build a place for the Kimbells' art collection. When he took the job, Brown said the new building should be a work of art itself. He wanted it to be "as much a gem as one of the Rembrandts or Van Dycks housed within it." The museum was given a 9.5-acre (3.8-hectare) spot in Fort Worth's Cultural District. This area already had three other museums. These included the Fort Worth Art Museum-Center (now the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth) and the Amon Carter Museum. The Amon Carter Museum specializes in art from the American West.

Brown talked about the museum's goals with the trustees. He wrote them down in a "Policy Statement" and a "Pre-Architectural Program" in June 1966. After talking to many famous architects, the museum chose Louis Kahn in October 1966. Brown gave Kahn specific requests, encouraging him to do his very best work. Brown wanted Kahn to build a museum that could show art to everyone. This way, a visit to the museum would give more opportunities to regular people. Kahn had designed other famous buildings, like the Salk Institute in California. He was also chosen to design the National Assembly Building for the new country of Bangladesh. Building for the Kimbell Art Museum started in the summer of 1969. The new building opened in October 1972. It quickly became known around the world for its amazing architecture.

Brown also made the Kimbell collection bigger. He bought important artworks by artists like Duccio, El Greco, Rubens, and Rembrandt.

After Richard Fargo Brown died in 1979, Edmund "Ted" Pillsbury became the museum's director. He had been the director of the new Yale Center for British Art. This museum was also designed by Louis Kahn. Pillsbury continued to buy art for the museum. Richard Brettell, who was the director of the Dallas Museum of Art, said that Pillsbury "single-handedly" helped the Kimbell become a museum whose art collection was as good as its building.

In 1989, Pillsbury announced plans to make the museum building bigger. This was to make space for its growing collection. However, the plan was stopped because many people did not want to change the original Louis Kahn building. In 2007, the Kimbell found a solution. They announced plans to build a new, separate building across the street from the original. This new building, designed by Renzo Piano, opened in November 2013. It did not change the Kahn building, but it did change how people approached Kahn's design. Kahn had wanted the building to be approached from the lawn.

The museum is part of the Monuments Men and Women Museum Network. This network was started in 2021 by the Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art.

Art Collection

In 1966, before the museum even had a building, director Brown wrote an important rule. He said, "The goal shall be definitive excellence, not size of collection." This means the museum wanted only the best art, not just a lot of it. Because of this, the museum's collection today has only about 350 artworks. But they are all very high quality.

The European art collection is the largest part of the museum. It includes Michelangelo's first known painting, The Torment of Saint Anthony. This is the only painting by Michelangelo on display in North or South America. The collection also has works by famous artists like Duccio, Fra Angelico, Mantegna, El Greco, Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Cézanne, Monet, Matisse, Picasso, and many others.

The museum also has ancient art from Ancient Egypt, Assyria, Greece, and Rome. The Asian collection includes sculptures, paintings, and other art from countries like China, Korea, Japan, and India. Precolumbian art from ancient American cultures like the Maya, Olmec, and Aztec is also on display. The African collection has sculptures from West and Central Africa. There is also Oceanic art, like a Maori figure.

The museum has very few pieces made after the mid-1900s. This is because its neighbor, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, focuses on that time period. It also has no American art, as that is the focus of its other neighbor, the Amon Carter Museum.

The museum also has a large library with over 59,000 books and magazines. This library is a helpful resource for art historians and students from nearby universities.

The Museum Building

Planning the Building

Brown's "Policy Statement" gave clear instructions for the building's design. It said the new building should be "a work of art." His "Pre-Architectural Program" added that "natural light should play a vital part" in the design. It also said that "the form of the building should be so complete in its beauty that additions would spoil that form." Brown wanted a building that was not too big, so it would not make the artwork or the visitors feel overwhelmed.

After a long search, the museum chose Louis Kahn in October 1966. Brown was a perfect client for Kahn. Brown had admired Kahn's work for a while. The way Brown wanted the building designed, especially with its focus on natural light, was very similar to Kahn's own ideas.

Kahn was known for sometimes taking a long time and spending more money than planned. So, a local engineering and architecture company, owned by Preston M. Geren, was hired to help. This was common in Fort Worth for architects from out of state. The contract said that Geren would take over construction once Kahn finished the design. This caused problems later because Kahn believed a design was never truly finished until the building was built. Kahn once said, "the building gives you answers as it grows and becomes itself." The museum trustees decided that Geren would report directly to them. However, Kahn would still have the final say on the design, but any changes needed Brown's approval.

The new museum was to be built on a gentle slope below the Amon Carter Museum. The Carter Museum's entrance faced the Fort Worth skyline. Kahn was asked to build the Kimbell museum no taller than 40 feet (12 m). This was so it would not block the view from the Carter Museum. Kahn first suggested a very wide building, 450 feet (137 m) square. But Brown said no. He insisted that Kahn design a much smaller building. This decision would cause problems years later when a plan to expand the building created a lot of disagreement.

Building Design

The museum is made of 16 parallel, curved roof sections called vaults. Each vault is 100 feet (30.6 m) long, 20 feet (6 m) high, and 20 feet (6 m) wide inside. Narrow, flat channels separate these vaults. The vaults are grouped into three sections or wings. The north and south wings each have six vaults. The westernmost vault in each of these wings is open, forming a portico (a porch with columns). The central section has four vaults. The westernmost vault here is an entry porch that faces a courtyard. This courtyard is partly surrounded by the two outer wings.

Most of the art galleries are on the upper floor of the museum. This allows them to get natural light. Service areas, offices for curators, and another gallery are on the ground floor. Each inside vault has a slot along its highest point. This slot lets natural light into the galleries. Air ducts and other mechanical systems are hidden in the flat channels between the vaults.

Kahn used several methods to make the galleries feel welcoming. The ends of the vaults are made of concrete blocks. They are covered with travertine stone both inside and out. The steel handrails were treated with ground pecan shells to give them a soft, matte texture. The museum has three courtyards with glass walls. These courtyards bring natural light into the gallery spaces. One of them goes through the gallery floor to bring light to the art conservation studio on the ground floor.

The museum's outdoor area is also very special. It has been called "Kahn's most elegant example of landscape planning." To reach the main entrance, visitors walk past a lawn with pools of running water. Then they enter a courtyard through a group of Yaupon Holly trees. The sound of footsteps on the gravel walkway echoes from the walls. It gets even louder under the curved ceiling of the entry porch. After this quiet walk, visitors enter the calm museum. Inside, silvery light spreads across the ceiling. Harriet Pattison played a main role in designing the landscape. She also suggested that open porches next to the entrance would create a good transition from the lawn to the galleries.

The Vaults

Kahn's first idea for the galleries had angled, curved roofs made of folded concrete. They had light slots at the top. Brown liked the light slots but did not like this design. The ceilings would have been 30 feet (9 m) high, which was too high for the museum he imagined. Further research by Marshall Meyers, Kahn's project architect, showed that using a cycloid curve for the vaults would make the ceiling lower. It would also offer other benefits. The flatter cycloid curve would create elegant galleries that were wide for their height. This allowed the ceiling to be lowered to 20 feet (6 m). More importantly, this curve could also spread natural light beautifully from a slot at the top of the gallery across the entire ceiling.

Kahn was happy with this idea. It allowed him to design galleries that looked like the ancient Roman vaults he admired. However, the thin, curved shells needed for the roof were hard to build. So, Kahn asked August Komendant, a top expert in concrete construction, for help. Kahn had worked with Komendant before. Kahn usually called the museum's roof shape a vault. But Komendant explained that it was actually a shell that acted like a beam. The shells that form the gallery roofs are "post-tensioned curved concrete beams." They stretch an amazing 100 feet (30.5 m). This was the longest distance concrete walls or vaults could be made without needing expansion joints. Both "vault" and "shell" are used to describe the museum in professional writings.

True vaults, like the Roman ones Kahn admired, need support along their entire sides or they will fall. Kahn did not fully understand how strong modern concrete shells could be. So, he first planned to include many more support columns than were needed for the gallery roofs. Komendant was able to use post-tensioned concrete that was only five inches thick. This created gallery "vaults" that only needed support columns at their four corners.

The Geren firm, which was asked to keep costs low, argued that the cycloid vaults would be too expensive. They suggested a flat roof instead. However, Kahn insisted on a vaulted roof. He believed it would create galleries with a comforting, room-like feeling. It would also need very few columns or other inside structures, which would make the museum more flexible. Eventually, a deal was made. Geren would be in charge of the foundation and basement. Komendant would be in charge of the upper floors and the cycloid shells. Kahn placed one of these shells at the front of each of the three wings as a porch or portico. This was to show how the building was built. He said the effect was "like a piece of sculpture outside the building."

Thos. S. Byrne, Ltd. was the company that built the museum. Their project superintendents designed forms with a cycloid shape. These forms were made from hinged plywood and coated with oil. This allowed them to be reused to pour concrete for many parts of the vaults, helping to make sure everything was consistent. The long, straight channels at the bottom of the shells were poured first. They were used as platforms to support the workers pouring concrete for the cycloid curves. After all the concrete was poured and strengthened with internal post-tensioning cables, the curved parts of the shells held the weight of their lower straight edges.

To stop the shells from collapsing at the long light slots at their top, concrete supports were put in every 10 feet (3 m). A thicker concrete arch was added to each end of the shells to make them even stronger. To show that the curved shells are only supported at their four corners, and not by the walls at the ends of the vaults, thin clear strips were put between the curve of the shells and the end walls. Because the strengthening arches of the shells are thicker at the top, the clear strips are thinner at the top than at the bottom. Also, a clear strip was placed between the straight bottoms of the shells and the long outside walls. This shows that the shells are not supported by those walls either. These features not only show how the building is made but also bring more natural light into the galleries in a way that is safe for the paintings.

The vault roofs, which visitors can see as they approach, were covered with lead. This was inspired by the lead roofs of the Doge's Palace and St. Mark's Basilica in Venice, Italy.

Skylights

David Brownlee and David DeLong, who wrote a book about Louis Kahn, said that "in Fort Worth, Kahn created a skylight system without peer in the history of architecture." Robert McCarter, another author, said the entry gallery is "one of the most beautiful spaces ever built," with its "astonishing, ethereal, silver-colored light." Carter Wiseman, who also wrote about Kahn, said that "the light in the Kimbell gallery assumed an almost ethereal quality, and has been the distinguishing factor in its fame ever since."

Creating a natural lighting system that received such praise was difficult. Kahn's office and the lighting designer Richard Kelly tried over 100 different ways to find the right skylight system. The goal was to light the galleries with indirect natural light. This means no direct sunlight, which would harm the artwork. Richard Kelly, the lighting expert, found that a special reflecting screen could spread natural light evenly across the curved ceiling. This screen was made of perforated anodized aluminum and had a specific curve. He hired a computer expert to figure out the exact shape of the reflector's curve. This made it one of the first parts of a building to be designed using computer technology.

In areas without art, like the lobby, cafeteria, and library, the entire reflector has holes. This allows people standing below to see clouds passing by. In the gallery spaces, the middle part of the reflector, which is directly under the sun, is solid. The rest of it has holes. The concrete ceilings were made very smooth to help reflect the light even more. The result is that the strong Texas sun enters a narrow slot at the top of each vault. It is then evenly reflected from a curved screen across the entire polished concrete ceiling. This creates a beautiful spread of natural light that had never been achieved before.

Museum Expansion

In 1989, director Ted Pillsbury, who took over after Brown, announced plans to add two new sections to the north and south ends of the building. He chose architect Romaldo Giurgola to design them. A huge wave of protests started. Critics pointed out that the first director, Brown, had said that "the form of the building should be so complete in its beauty that additions would spoil that form." They also said that Kahn had achieved this goal incredibly well.

A group of famous architects signed a letter. They agreed that more space was needed. But they argued that the planned addition would ruin the original building's design. They noted that when Kahn himself was asked about future expansion, he said it should "occur as a new building and be situated away from the present structure across the lawn." Esther Kahn, Louis Kahn's widow, also wrote a letter saying similar things. She noted that "there is room on the site for a separate building, which could be connected to the present museum." The project was canceled a few months later.

Renzo Piano Pavilion

In 2006, the idea of expanding the museum came up again. This time, the new plan was exactly what Louis Kahn himself had thought for expansion: a separate building. At that time, the new building was planned for land behind the Kahn building.

In April 2007, the museum announced that Renzo Piano had been chosen to design the new building. Piano was a clear choice because he had worked in Louis Kahn's office when he was young. He had also become known as one of the world's best museum architects. Piano had designed other famous museums, like the Menil Collection in Houston. He also designed the expansion for the Art Institute of Chicago and was a co-designer of the Pompidou Centre in Paris.

The first designs for the new Kimbell building were shown in November 2008. The full plans were released in May 2010. The new building, called the Renzo Piano Pavilion, is 85,000 square feet (7,900 m2). It was designed to go well with the original building but not copy it. Unlike the original, its lines are straight, not curved. However, like the original, it has three sections, with the middle section set back from the other two. The new building officially opened to the public on November 27, 2013.

The new building also helped solve a parking problem at the museum. Kahn did not like how cars affected city life. He once talked about "the destruction of the city by the motor car." He did not want buildings to be designed around cars. So, Kahn put the main parking lot at the back of the building. He wanted visitors to walk around the building and enter through the carefully planned landscape. However, most visitors entered through the back door on the ground floor. This meant they missed the special entry experience Kahn had designed. The new building solved this problem with an underground parking garage. After visitors go up to the gallery level of the new building, they can walk across the lawn and courtyard to enter the original building, just as Kahn had planned.

Awards and Recognition

- In 1998, the American Institute of Architects gave the museum their important Twenty-five Year Award. This award is given to no more than one building each year.

- Robert Campbell, an architecture critic, called it "the greatest American building of the second half of the 20th century."

- Robert McCarter, author of Louis I. Kahn, said that the Kimbell Art Museum "is rightly considered Kahn's greatest built work." He also said it "has been the subject of more scholarly studies than all his other works combined."

- Carter Wiseman, author of Louis I. Kahn: Beyond Time and Style, said that with the Kimbell, Kahn created something unique. He made a building that used natural sunlight in an amazing way. It combined a modern purpose with advanced engineering, while also reminding people of old monuments.

- Thos. S. Byrne, Ltd., the construction company, won the first Build America Award in 1972. This was for the "innovative construction techniques" used on the museum.

European Art Highlights

-

Georges de La Tour, The Cheat with the Ace of Clubs, c. late 1620s; another version is in the Louvre.

-

Duccio di Buoninsegna, The Raising of Lazarus, 1310

-

Caravaggio, The Cardsharps, 1594

-

Annibale Carracci, The Butcher's Shop, 1580

-

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Happy Age! Golden Age, 1716–1720

-

Gustave Caillebotte, On the Pont de l’Europe, 1876–1877

-

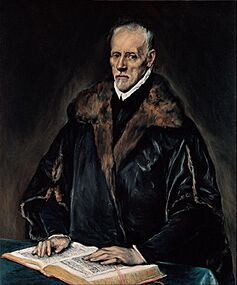

El Greco, Portrait of Dr Francisco de Pisa, c. 1610–1614

-

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Don Pedro de Barberana, 1632

-

Jean Siméon Chardin, Young Student Drawing, c. 1738

-

Théodore Géricault, Portrait of a Boy with Long Blond Hair, 1819–1820

-

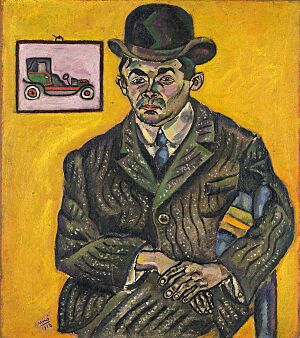

Paul Gauguin, Self-Portrait, 1885

-

Paul Cézanne, Man in a Blue Smock, 1896–1897

-

Frederic Leighton, Portrait of May Sartoris at about 15 years of age, 1860

Asian Art Highlights

Museum Management

The Kimbell Art Museum gets about 65% of its $12 million budget from its special fund, which is over $400 million. This fund helps the museum operate. The museum does not have separate funds just for buying new art. About 15,000 people are members of the museum. In 2019, the museum hired Guillaume Kientz as the curator of European art. He used to work at the Louvre museum.

See also

In Spanish: Museo de Arte Kimbell para niños

In Spanish: Museo de Arte Kimbell para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |