El Greco facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

El Greco

|

|

|---|---|

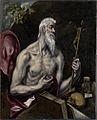

Portrait of a Man (thought to be El Greco, c. 1595–1600) in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

|

|

| Born |

Domḗnikos Theotokópoulos

1 October 1541 either Fodele or Candia, Crete

|

| Died | 7 April 1614 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | Venetian-Greek and Spanish |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture and architecture |

|

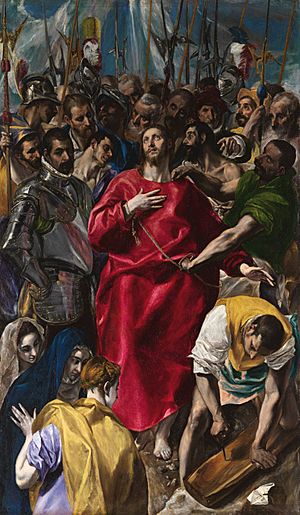

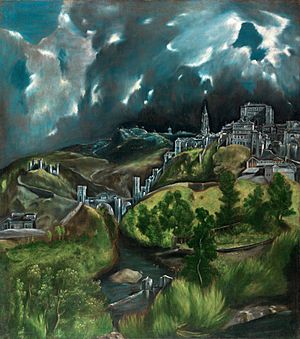

Notable work

|

El Expolio (1577–1579) The Assumption of the Virgin (1577–1579) The Burial of the Count of Orgaz (1586–1588) View of Toledo (1596–1600) Opening of the Fifth Seal (1608–1614) |

| Movement | Mannerism Spanish Renaissance |

Domḗnikos Theotokópoulos (Greek: Δομήνικος Θεοτοκόπουλος; 1 October 1541 – 7 April 1614) is best known as El Greco. This nickname means "The Greek" in Spanish. He was a Greek painter, sculptor, and architect during the Spanish Renaissance. El Greco usually signed his paintings with his full Greek name. He often added the word "Cretan" to show where he was from.

El Greco was born in Crete, which was then part of Venice, Italy. Crete was a major center for Byzantine art. He learned to paint in this style before moving to Venice at age 26. In 1570, he moved to Rome. While in Italy, El Greco developed his unique style. He was influenced by Mannerism and the Italian Renaissance, especially by artists like Tintoretto. In 1577, he moved to Toledo, Spain. He lived and worked there until he died. In Toledo, El Greco created his most famous paintings. These include View of Toledo and Opening of the Fifth Seal.

El Greco's dramatic and expressive art puzzled people in his time. But in the 20th century, his work became very popular. Many see him as an early influence on Expressionism and Cubism. His unique style combines Byzantine art traditions with Western painting. He is known for his tall, stretched-out figures and bright, unusual colors.

About El Greco's Life

His Early Years and Family

El Greco was born in 1541. He was from a well-off family in either Fodele or Candia (now Heraklion) on Crete. His father, Geṓrgios Theotokópoulos, was a merchant and tax collector. We don't know much about his mother or his first wife. His older brother, Manoússos, was a rich merchant. Manoússos spent his last years living with El Greco in Toledo.

El Greco first trained as an icon painter in the Cretan school. This was a leading center for post-Byzantine art. He likely also studied ancient Greek and Latin writings. When he died, he had a library of 130 books. Candia was a busy art center. About 200 painters worked there in the 16th century. They even had a painters' guild, like in Italy.

In 1563, at age 22, El Greco was called a "master." This means he was already a master of the guild. He likely had his own workshop. Three years later, in 1566, he signed his name in Greek as "Master Ménegos Theotokópoulos, painter."

Most experts believe El Greco's family was Greek Orthodox. Some Catholic sources still claim he was Catholic from birth. Like many Orthodox people who moved to Catholic areas, some think he might have become Catholic later. He described himself as a "devout Catholic" in his will. But research shows his family was Greek Orthodox. One of his uncles was an Orthodox priest. His name is not in Catholic baptism records on Crete.

While still in Crete, El Greco painted Dormition of the Virgin. This was probably before 1567. Three other signed works are also thought to be by him from this early period. These include Modena Triptych and The Adoration of the Magi.

Moving to Italy

It was natural for El Greco to go to Venice. Crete had been owned by Venice since 1211. Most experts agree El Greco went to Venice around 1567. We don't know much about his time in Italy. He lived in Venice until 1570. A friend, Giulio Clovio, said El Greco was a "disciple" of Titian. This might mean he worked in Titian's large studio. Clovio called El Greco "a rare talent in painting."

In 1570, El Greco moved to Rome. There he created many works influenced by his Venetian training. We don't know how long he stayed in Rome. He might have returned to Venice around 1575–76 before going to Spain. In Rome, El Greco stayed at the Palazzo Farnese. This palace was a center for art and ideas. He met important thinkers there, like Fulvio Orsini. Orsini later owned seven of El Greco's paintings.

Unlike other Cretan artists, El Greco changed his style a lot. He wanted to create new and unusual religious art. His Italian paintings show the Venetian Renaissance style. They have long, agile figures like Tintoretto's. Their colors are similar to Titian's. Venetian painters also taught him to arrange many figures in landscapes with special light.

Clovio once visited El Greco in Rome. El Greco was sitting in a dark room. He said darkness helped him think better than daylight. Because of his time in Rome, his art gained new elements. These included strong perspective and figures with twisted, dramatic poses. These are all signs of Mannerism.

When El Greco arrived in Rome, Michelangelo and Raphael had already died. But their art was still very important. El Greco wanted to make his own mark. He praised artists like Correggio and Parmigianino. But he openly criticized Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. He even offered to repaint it for Pope Pius V. When asked about Michelangelo, El Greco said he was "a good man, but he did not know how to paint." Yet, Michelangelo's influence can be seen in El Greco's later works. By painting portraits of Michelangelo, Titian, Clovio, and Raphael in his work The Purification of the Temple, El Greco showed his respect. He also showed he aimed to be as great as them.

Because of his unusual ideas and strong personality, El Greco soon made enemies in Rome. An architect called him a "foolish foreigner." He even had a disagreement with Farnese, who made him leave his palace. In September 1572, he joined the Guild of Saint Luke in Rome as a miniature painter. By the end of that year, El Greco opened his own workshop. He hired assistants to help him.

Life in Spain

Moving to Toledo

In 1577, El Greco moved to Madrid, then to Toledo. Toledo was Spain's religious capital at the time. It was a busy city with a rich history. In Rome, El Greco had gained respect from some thinkers. But he also faced criticism from others. In the 1570s, the large El Escorial monastery-palace was being built. Philip II of Spain needed good artists to decorate it. Titian had died, and other famous artists refused to come to Spain. So, the time was right for El Greco to move to Toledo.

Through his friends Clovio and Orsini, El Greco met important Spanish people. These included Benito Arias Montano, an agent for King Philip, and Luis de Castilla, whose father was a dean at the Toledo Cathedral. El Greco's friendship with Castilla helped him get his first big jobs in Toledo. He arrived in Toledo by July 1577. He signed contracts for paintings for the church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo and for the famous El Espolio. By September 1579, he had finished nine paintings for Santo Domingo. These works made him famous in Toledo.

El Greco didn't plan to stay in Toledo forever. He wanted to impress King Philip and work at his court. He did get two important jobs from the king: Allegory of the Holy League and Martyrdom of St. Maurice. However, the king did not like these paintings. He put the St Maurice altarpiece in a less important place. He never gave El Greco any more jobs. We don't know exactly why the king was unhappy. Some think Philip didn't like seeing living people in a religious scene. Others believe El Greco's art broke rules of the Counter-Reformation. These rules said that the message of the art was more important than its style.

Later Years and Famous Works

Since the king didn't favor him, El Greco had to stay in Toledo. He had been welcomed there as a great painter in 1577. A poet from that time said, "Crete gave him life and his art, Toledo a better home." In 1585, he hired an assistant, Francisco Preboste. He also set up a workshop that made altar frames and statues, as well as paintings. On March 12, 1586, he got the job to paint The Burial of the Count of Orgaz. This is now his most famous work.

The years from 1597 to 1607 were very busy for El Greco. During this time, he received several big commissions. His workshop created many paintings and sculptures for churches. Some of his main jobs included three altars for the Chapel of San José in Toledo (1597–1599). He also painted three works (1596–1600) for a monastery in Madrid. He also created a main altar, four side altars, and a painting for a hospital in Illescas (1603–1605). Documents from the time called El Greco "one of the greatest men in both this kingdom and outside it."

Between 1607 and 1608, El Greco had a long legal fight. It was with the hospital in Illescas over payment for his work. This and other legal problems caused him money troubles later in life. In 1608, he got his last major job at the Hospital of Saint John the Baptist in Toledo.

El Greco made Toledo his permanent home. Records show he rented a large place from 1585. It had three apartments and 24 rooms. He used these rooms as his home and workshop. He lived in style, sometimes having musicians play while he ate. He lived with Jerónima de Las Cuevas, but they probably never married. She was the mother of his only son, Jorge Manuel, born in 1578. Jorge Manuel also became a painter. He helped his father and continued his father's style after inheriting the studio. In 1604, Jorge Manuel had a son, Gabriel, El Greco's grandson.

While working on a job for the Hospital de Tavera, El Greco became very ill. He died a month later, on April 7, 1614, at age 73. A few days before, he had arranged for his son to handle his will. Two Greek friends witnessed his will. El Greco never forgot his Greek roots. He was buried in the Church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo.

El Greco's Art

His Unique Style

El Greco believed that imagination and intuition were key to creating art. He didn't follow traditional rules of size and balance. He thought that true art showed grace. A painter achieved grace by solving difficult problems easily.

El Greco saw color as the most important and hardest part of painting. He said color was more important than shape. Francisco Pacheco, a painter who visited El Greco in 1611, wrote that El Greco liked "crude and unmixed colors in great blots." He also said El Greco believed in constantly repainting to make colors look natural.

"I hold the imitation of color to be the greatest difficulty of art."

Art experts now describe El Greco's ideas as "Mannerist." They link his style to Neoplatonism from the Renaissance. Jonathan Brown believes El Greco created a very complex art form. Nicholas Penny says that once in Spain, El Greco developed his own style. This style ignored most of the usual ways of showing things in painting.

In his later works, El Greco showed a strong desire to make things dramatic, not just describe them. His paintings create strong spiritual feelings in the viewer. Pacheco said El Greco's wild and sometimes messy art was a way to achieve freedom in his style. El Greco preferred very tall and thin figures. He also liked long compositions. These choices helped him express his ideas and artistic rules. He often ignored natural laws and stretched his figures even more. This was especially true for paintings meant for altars.

In El Greco's mature works, human bodies look even more otherworldly. For The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, El Greco asked to make the altarpiece taller. He said this would make the figures "perfect and not reduced." A key new idea in his later art is how form and space mix together. They create a unified painting surface. This idea would reappear centuries later in the works of Cézanne and Picasso.

Another feature of El Greco's later style is his use of light. Jonathan Brown notes that "each figure seems to carry its own light within." Or they reflect light from a hidden source. Scholars who studied El Greco's notes link his use of light to Christian Neo-Platonism.

Modern research shows how important Toledo was for El Greco's style to fully develop. It highlights his ability to change his style to fit his surroundings. Experts say that El Greco, though Greek by birth and Italian by training, became deeply connected to Spain's religious life. He became a key artist for Spanish mysticism. His later works show the strong religious feeling of Catholic Spain during the Counter-Reformation.

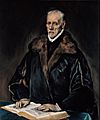

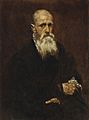

El Greco was also an excellent portrait painter. He could not only show what people looked like but also their true character. He painted fewer portraits than religious scenes. But his portraits are just as high quality. One expert said El Greco's portraits put him among the best, like Titian and Rembrandt.

Painting Materials

El Greco painted many of his works on fine canvas. He used a thick oil paint. He used common pigments of his time. These included azurite, lead-tin-yellow, vermilion, madder lake, ochres, and red lead. But he rarely used the expensive natural ultramarine.

Byzantine Influences

Since the early 1900s, experts have argued if El Greco's style came from Byzantine art. Some art historians said his roots were clearly Byzantine. They believed his unique traits came directly from his ancestors' art. Others argued that Byzantine art had nothing to do with his later work.

"I would not be happy to see a beautiful, well-proportioned woman, no matter from which point of view, however extravagant, not only lose her beauty in order to, I would say, increase in size according to the law of vision, but no longer appear beautiful, and, in fact, become monstrous."

The discovery of his Dormition of the Virgin in Syros helped restart these discussions. This was a real, signed work from his time in Crete. Even though it follows many Byzantine icon rules, it also shows Venetian influence. The painting combines Orthodox and Catholic ideas about Mary's death and her Assumption. Many important studies in the late 20th century looked again at El Greco's work. They included his supposed Byzantine ties. Based on his own notes, his unique style, and his Greek signature, they see a clear link between Byzantine painting and his art.

One expert, Marina Lambraki-Plaka, believes that away from Italy, in a place like his birthplace, Crete, his Byzantine training came out. It played a big role in his new way of seeing images in his later work. However, some disagree. They say the only Byzantine part of his famous paintings was his Greek signature. Another expert, Nikos Hadjinikolaou, states that from 1570, El Greco's painting is "neither Byzantine nor post-Byzantine but Western European."

David Davies, an English art historian, looks for the roots of El Greco's style in his Greek-Christian education. He also looks at his memories of Orthodox Church ceremonies. Davies thinks the religious mood of the Counter-Reformation and the style of Mannerism helped shape his unique technique. He believes that ideas from Platonism and ancient Neo-Platonism, along with Church writings, help us understand El Greco's style.

Architecture and Sculpture

El Greco was also respected as an architect and sculptor during his life. He often designed entire altar pieces. He worked as an architect, sculptor, and painter. For example, at the Hospital de la Caridad, he decorated the chapel. But the wooden altar and sculptures he made there are probably gone. For El Espolio, he designed the original gilded wooden altar, which was destroyed. But his small sculpture group of the Miracle of St. Ildefonso still remains on the lower part of the frame.

His most important architectural work was the church and Monastery of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. He also made sculptures and paintings for it. El Greco is seen as a painter who included architecture in his art. He is also known for designing the architectural frames for his own paintings in Toledo. Pacheco called him "a writer of painting, sculpture and architecture."

In his notes, El Greco disagreed with the architect Vitruvius. He didn't like Vitruvius's focus on old ruins, standard sizes, perspective, and math. He also thought Vitruvius's way of changing sizes to look right from a distance made figures look strange. El Greco disliked the idea of strict rules in architecture. He believed in freedom to create new, varied, and complex designs. However, these ideas were too extreme for his time and didn't catch on right away.

El Greco's Legacy

How People Saw His Art After He Died

After El Greco died, people didn't appreciate his work much. His art was very different from the early baroque style that became popular in the 17th century. El Greco's art was hard to understand, and he had no important students. Only his son and a few unknown painters made weak copies of his works. Spanish writers in the late 1600s and early 1700s praised his skill. But they criticized his unnatural style and complex symbols. Some called his later work "contemptible" and "ridiculous." These views were often repeated in Spanish art history. His art was called "strange," "queer," "original," and "odd." The idea that he was "sunk in eccentricity" eventually turned into "madness."

With the rise of Romanticism in the late 1700s, people looked at El Greco's art again. To French writer Théophile Gautier, El Greco was a pioneer of the European Romantic movement. He saw El Greco as the perfect romantic hero—"gifted," "misunderstood," and "mad." Gautier was the first to openly admire El Greco's later painting style. French art critics Zacharie Astruc and Paul Lefort helped bring back interest in his paintings. In the 1890s, Spanish painters in Paris looked to him as a guide.

In 1908, Spanish art historian Manuel Bartolomé Cossío published the first full list of El Greco's works. In this book, El Greco was presented as the founder of the Spanish School. That same year, Julius Meier-Graefe, an expert on French Impressionism, traveled to Spain. He expected to study Velásquez but became fascinated by El Greco. He wrote about his experiences in Spanish Journey. This book made El Greco widely known as a great painter. Meier-Graefe saw hints of modern art in El Greco's work.

To English artist and critic Roger Fry in 1920, El Greco was the perfect genius. He did what he thought was best "with complete indifference to what effect the right expression might have on the public." Fry called El Greco "an old master who is not just modern, but actually appears many steps ahead of us."

At the same time, other researchers came up with different ideas. Eye doctors August Goldschmidt and Germán Beritens said El Greco painted stretched-out figures because he had vision problems. They thought he might have seen bodies longer than they were. Michael Kimmelman, a reviewer for The New York Times, said that "to Greeks [El Greco] became the quintessential Greek painter; to the Spanish, the quintessential Spaniard."

Jimmy Carter, the 39th President of the United States, said in 1980 that El Greco was "the most extraordinary painter that ever came along back then." He added that El Greco was "maybe three or four centuries ahead of his time."

How He Influenced Other Artists

According to Efi Foundoulaki, artists and thinkers in the early 20th century "discovered" a new El Greco. In doing so, they also showed something about themselves. His expressive style and colors influenced Eugène Delacroix and Édouard Manet. The Blaue Reiter group in Munich in 1912 saw El Greco as a symbol of the "mystical inner construction" they wanted to find again.

Paul Cézanne, one of the artists who led to Cubism, was the first to notice the structure in El Greco's later art. Comparing the two painters shows their common elements. These include the way they changed the human body, their reddish backgrounds, and how they showed space. According to Brown, "Cézanne and El Greco are spiritual brothers." Fry noted that Cézanne learned from El Greco's "great discovery of the permeation of every part of the design with a uniform and continuous plastic theme."

The Symbolists and Pablo Picasso during his Blue Period used El Greco's cool colors. They also used the thin bodies of his figures. While Picasso was working on his early Cubist painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, he visited his friend Ignacio Zuloaga. He studied El Greco's Opening of the Fifth Seal, which Zuloaga owned. The connection between Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and the Opening of the Fifth Seal was noted in the early 1980s.

Picasso's early Cubist works found other things in El Greco's art. These included how he structured his paintings, how he showed forms from many angles, how form and space mixed, and his special lighting effects. Several parts of Cubism, like distortions and showing time in a physical way, are similar to El Greco's work. Picasso said El Greco's structure is Cubist. In 1950, Picasso started a series of "paraphrases" of other painters' works. One was The Portrait of a Painter after El Greco.

The Expressionists focused on El Greco's expressive distortions. Franz Marc, a main German Expressionist painter, said, "we refer with pleasure and with steadfastness to the case of El Greco." He felt El Greco's fame was tied to their new ideas about art. Jackson Pollock, a major artist in the abstract expressionist movement, was also influenced by El Greco. By 1943, Pollock had made sixty drawings based on El Greco. He also owned three books about the Cretan master.

Kysa Johnson used El Greco's paintings of the Immaculate Conception as a base for some of her works. El Greco's body distortions are also seen in Fritz Chesnut's portraits.

El Greco's life and art inspired poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Some of Rilke's poems (Himmelfahrt Mariae I.II., 1913) were directly based on El Greco's Immaculate Conception. Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis felt a strong connection to El Greco. He named his autobiography Report to Greco and wrote a tribute to the artist.

In 1998, the Greek electronic composer Vangelis released El Greco. This was a symphonic album inspired by the artist. This album was an expanded version of an earlier album by Vangelis, Foros Timis Ston Greco (A Tribute to El Greco). The life of the Cretan-born artist is also the subject of the film El Greco. This film was made by Greek, Spanish, and British companies. It started filming in October 2006 on Crete and came out a year later. British actor Nick Ashdon played El Greco.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: El Greco para niños

In Spanish: El Greco para niños

- El Greco Museum, Toledo, Spain

- Museum of El Greco, Fodele, Crete

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |