August Komendant facts for kids

August Eduard Komendant (born October 2, 1906 – died September 14, 1992) was an engineer from Estonia who later became an American citizen. He was a pioneer in using a special type of concrete called prestressed concrete. This concrete is much stronger and can be used to build more elegant structures than regular concrete.

Komendant was born in Estonia and studied engineering in Germany. After World War II, he moved to the United States. There, he wrote several books about structural engineering. He also taught architecture at the University of Pennsylvania.

Komendant worked with the famous architect Louis Kahn from 1956 until Kahn's death in 1974. Their work together was very successful, even though they often argued. Komendant's new ideas as Kahn's structural engineer helped Kahn create many important buildings. Two of these buildings won the special Twenty-five Year Award from the American Institute of Architects. Komendant also worked as the structural engineer for architect Moshe Safdie on the Habitat 67 project in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Contents

Life

August E. Komendant was born in 1906 in Mäo Parish, Estonia. He studied engineering at the Technical Institute in Dresden, Germany. After his studies, he went back to Estonia. There, he was in charge of building several big bridges and other structures.

During World War II, Germany took over Estonia. Komendant was sent back to Germany to work on war projects. Later in the war, the U.S. Army held him. General George Patton then asked him to work for him. Komendant said that Patton once asked him to check a damaged bridge. Patton wanted to know if his tanks could cross it. Komendant used paint to mark a wavy path across the bridge. This path was safe for the tanks to follow. He then rode across the bridge with Patton. After the war, he helped the U.S. Army rebuild bridges damaged by the war.

In 1950, Komendant moved to the U.S. He started his own engineering business in New Jersey. In 1952, he published a book called Prestressed Concrete Structures. This book made him an expert on the topic. He had learned a lot about prestressed concrete while rebuilding bridges.

Komendant liked to explain how prestressed concrete works. He would show that you can lift a row of books by squeezing them tightly. When squeezed, they act like one strong unit. In the same way, steel cables or bars can be pulled very tight to "squeeze" concrete. This makes the concrete much stronger. This type of concrete can be used to build lighter, more graceful structures. They can also be made in many more shapes than regular concrete.

Komendant was a Professor of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania. He taught there from 1959 to 1974. He was also a visiting professor at the Pratt Institute in the late 1970s.

Collaboration with Louis Kahn

In 1956, Komendant met architect Louis Kahn. Kahn soon became one of the most respected architects of his time. They started working together, and their partnership lasted 18 years. It was very productive, but they often argued. Kahn was five years older than Komendant. Like Komendant, he had also been born in Estonia.

In the early 1950s, Kahn decided he would no longer use lightweight steel structures. These were common in modern buildings. He believed that only structures made of reinforced concrete would let him achieve his goals. He wanted buildings that could support themselves, shape spaces, and be beautiful sculptures all at once.

This approach needed a structural engineer who understood Kahn's ideas. The engineer had to see what Kahn wanted to create. They also had to suggest other ways if a design was not practical. Komendant was already known for his skill with pre-stressed concrete. He proved to be a creative thinker and a great partner. Kahn called him "one of the rare engineers qualified to guide the architect to develop meaningful form." Robert McCarter, who wrote about Kahn, said Komendant "would serve as Kahn's primary consultant on the majority of his commissions for the rest of his career."

Their first project together was the Richards Medical Research Laboratories. This building was a big step for Kahn. It was the first time his work received wide praise. Two other buildings they worked on, the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and the Kimbell Art Museum, won the important Twenty-five Year Award. This award is given to only one building each year by the American Institute of Architects.

Both men knew they did their best work together. But it was not always easy. Komendant worked very fast, while Kahn was famously slow. This often frustrated Komendant. Komendant felt free to criticize Kahn's designs, not just as an engineer but also as an architect. This sometimes made Kahn feel his role was questioned. Kahn would then remind Komendant that he was an engineer, not an architect. Komendant, in turn, enjoyed teasing Kahn about his lack of engineering knowledge.

Komendant also liked to take more credit for shared projects. Kahn found it hard to share credit with anyone. These issues led Komendant to skip the opening of the Kimbell Art Museum. This was one of Kahn's greatest works, and Komendant had helped a lot with it.

In the early 1960s, they worked on the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, Bangladesh. But Komendant left the project after a big disagreement with Kahn. They were not close for about three years after that. However, during this time, they still worked together on the Salk Institute. They also remained colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania.

Despite their sometimes difficult relationship, they were very proud of their shared work. Thomas Leslie, who wrote a book about Kahn, said Komendant "deeply loved the work he did with Kahn." He added that these buildings were Komendant's most famous and honored projects. Kahn himself recognized Komendant's help. In Komendant's book, 18 years with Architect Louis I. Kahn, Kahn wrote: "To August whose genius has made my buildings his buildings and are the very ones that have wonder about them."

Thomas Leslie described their relationship well. He said Komendant was not a designer, and Kahn did not have Komendant's math skills. Each needed the other. Their teamwork led to buildings where structure and architecture were perfectly combined. This would not have happened without their arguments and debates.

Richards Medical Research Laboratories

For the eight-story Richards Medical Research Laboratories (1957–1965) in Philadelphia, PA, Komendant designed the structure. It used concrete pieces that were made in a factory. These pieces included columns, beams, and trusses. They were brought to the site by truck and put together with a crane. Then, strong cables inside the concrete were pulled tight. This locked the pieces together, like a child's toy that is loose until its parts are pulled tight with a string.

There were 1019 of these concrete pieces. For the cables to work well, the pieces had to be made very precisely. Komendant worked closely with the factory to make sure this happened. The finished building had very little difference between any two pieces, less than 1⁄16 inch (1.6 mm).

Kahn believed that the structure of a building should be seen. So, he showed these concrete parts on the outside of the building and in the lab ceilings. He also left the ceiling of the entry porch open. This allowed people to see the structure, including the Vierendeel trusses. These trusses look like ladders on their sides. Their large, rectangular openings make it easy to run pipes and ducts into the laboratories.

Even though the building had some problems for the scientists working there, it was praised worldwide. It was admired for its architecture and new building methods. In 1961, the Museum of Modern Art held an exhibition just for this building. They called it "probably the single most consequential building constructed in the United States since the war." Architectural historian Vincent Scully said Kahn and Komendant's work on this project "was to affect for good the techniques of the whole concrete pre-casting industry." The Architectural Record noted that the precision was "more typical of fine cabinetwork than of concrete construction."

Salk Institute for Biological Studies

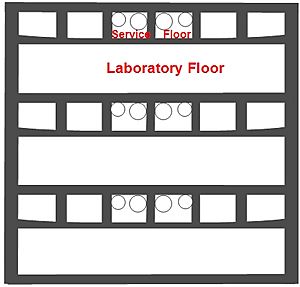

At the Salk Institute for Biological Studies (1959–1965) in La Jolla, CA, many mechanical systems were needed. These included air ducts and pipes. Kahn decided to create a separate service floor above each laboratory floor. This made it easier to change the labs later without disturbing other areas. He also designed each lab floor to have no support columns inside. This made lab setup simpler.

Komendant designed the Vierendeel trusses that made this possible. These pre-stressed concrete trusses are about 62 feet (19 m) long. They span the full width of each floor. They go from the bottom to the top of each service floor. They are supported by steel cables inside the concrete. These cables are curved, like those on a suspension bridge. The trusses have rectangular openings, 6 feet (1.8 m) high in the middle. These openings allow workers to move easily through the pipes and ducts on the service floors. The trusses put weight straight down on their support columns. They are attached in a way that allows small movements during earthquakes.

After two years of design, and even after the design was approved, Kahn and the Salk Institute changed their minds. They decided to have two wider lab buildings instead of four narrow ones. They also increased the number of floors from two to three. Komendant quickly redesigned the structure and made new drawings. Professor Leslie called his speed "legendary." Komendant also taught the construction workers how to create a very smooth concrete finish.

In 1992, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) gave this building its important Twenty-five Year Award. This award is given to only one building each year.

First Unitarian Church of Rochester

At the First Unitarian Church (1959–1969) in Rochester, NY, Kahn faced a challenge. He needed to place a heavy concrete roof between four light towers in the corners of the main room. He did not want any support columns inside the room. Kahn was not fully happy with his roof design. He asked Komendant for ideas.

Komendant kept Kahn's general roof shape. But he redesigned it as a folded-plate structure of prestressed concrete. This design would only need support at its edges. This removed the need for the huge concrete beams Kahn had planned. Kahn used Komendant's design, with some changes.

The builder had no experience with this type of roof. So, Komendant agreed to check the forms before concrete was poured. He also returned after the concrete dried to oversee the tightening of the internal support cables. The builder worried the heavy roof would fall when the forms were removed. But Komendant promised it would settle no more than 1⁄4 inch (6.4 mm). It actually settled less than 1⁄8 inch (3.2 mm).

Paul Goldberger, a writer about architecture and a Pulitzer Prize for Criticism winner, called this building one of the "greatest religious structures of this century" in 1982.

Olivetti-Underwood Factory

For the Olivetti-Underwood Factory (1966–1970) in Harrisburg, PA, the Olivetti company hired Louis Kahn to design their factory. Olivetti was known for its good design. Komendant designed the building's structure. It used 72 prestressed concrete units. These units were locked together in a grid to form the roof and its support system.

Each unit is a concrete shell that looks like a square dish with cut corners. It sits on top of a thin concrete column. Each shell is 30 feet (9.1 m) above the factory floor and 60 feet (18 m) across. It covers 3,600 square feet (330 m2) of roof space.

Kimbell Art Museum

At the Kimbell Art Museum (1966–1972) in Fort Worth, TX, Komendant was key in designing the curved concrete gallery roofs. These roofs do not need support inside, which keeps the gallery floors open. Before Komendant joined, Kahn was designing the curved roofs as vaults. These would need columns along their edges.

Komendant realized the roofs should be designed as vault-shaped beams. These would only need support at their four corners. These beams are supported by cables, similar to those on a suspension bridge. But these cables run inside tubes embedded in the curved concrete. After the concrete hardened, hydraulic force was used to pull the hidden cables tight.

Professor Steven Fleming said the result was "post-tensioned curved concrete beams, spanning an incredible 100 feet" (30.5 m). This was the longest distance concrete walls or vaults could be made without needing special joints to allow for movement.

Just like at the Salk Institute, Komendant personally trained the construction workers. He taught them how to create a very smooth concrete finish. Professor Leslie said Komendant "almost single-handedly assured the resulting concrete finishes, by far the best on a Kahn building."

Komendant also helped solve a problem between Kahn and the local engineering firm. This firm was in charge of the museum's design and building. The firm thought the curved roofs were not safe and suggested a flat roof instead. This disagreement became a big problem, threatening the whole project. To fix it, Komendant was given full control over the final design and building plans. Professor Leslie said Komendant "was demonstrably the major influence in Kahn being kept on the job, and in the project being done at all."

Robert Campbell, an architecture writer and Pulitzer Prize for Criticism winner, called the Kimbell Art Museum "the greatest American building of the second half of the 20th century." In 1998, the AIA gave this building its Twenty-five Year Award.

Other major work

From 1964 to 1967, when he and Kahn were not close, Komendant worked with architect Moshe Safdie. This was on the Habitat 67 project in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Safdie was only 25 years old and had never built anything before. He got the job to build homes for Montreal's Expo 67 based on his university project. Safdie and Komendant had met when Safdie was learning in Kahn's office. Safdie asked Komendant to be the structural engineer for the project. Komendant designed the systems for making parts of the building in a factory.

The complex, called Habitat 67, first had 354 concrete containers. These were all the same size and made in a factory. They were put together with a crane. They formed 158 apartments in 19 different sizes. The complex is about four blocks long and up to eleven levels high. Each apartment has its own private terrace and garden. Habitat 67 has become a very popular place to live in Montreal. Many cultural and political leaders live there.

Publications and awards

Komendant wrote several books, including:

- Prestressed Concrete Structures, 1952

- Contemporary Concrete Structures, 1972

- 18 years with Architect Louis I. Kahn, 1975

- Practical Structural Analysis for Architectural Engineering, 1987

In his book 18 years with Architect Louis I. Kahn, Komendant included a letter from Kahn. Kahn had written to the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1973. He recommended that Komendant receive the AIA's Allied Professions Medal. According to his obituary in the New York Times, the AIA gave Komendant a medal in 1978. It was for "inspiring or influencing the architectural profession."

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |