Bernardino de Sahagún facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

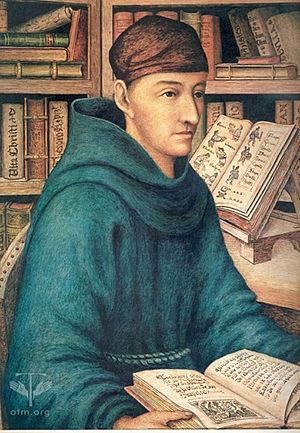

The Reverend

Bernardino de Sahagún

OFM

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Bernardino de Ribeira

c. 1499 |

| Died | 5 February 1590 (aged 90–91) |

| Occupation | Franciscan missionary |

| Signature | |

Bernardino de Sahagún (born around 1499 – died February 5, 1590) was a Franciscan friar and missionary priest. He was one of the first people to study different cultures, especially the Aztecs in what is now Mexico.

Born in Sahagún, Spain, he traveled to New Spain (which is now Mexico) in 1529. He learned Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. He spent over 50 years studying Aztec beliefs, culture, and history. His amazing work documenting their way of life earned him the title "the first anthropologist." He also helped describe the Nahuatl language. He translated important Christian texts like the Psalms and the Gospels into Nahuatl.

Sahagún is best known for his huge work called Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España. This means General History of the Things of New Spain. The most famous copy of this book is the Florentine Codex. It has 2,400 pages and 12 books, with about 2,500 pictures drawn by native artists. The text is in both Spanish and Nahuatl. It describes the Aztec culture, their beliefs, daily life, economy, and history. Book 12 even tells the story of the Spanish conquest from the Aztec point of view.

Sahagún created new ways to gather information about cultures and check if it was accurate. His Historia general is called "one of the most remarkable accounts of a non-Western culture ever composed." In 2015, his work was recognized as a World Heritage by UNESCO.

Contents

- Early Life and Education in Spain

- Missionary Work in New Spain

- At the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco

- Sahagún's Missionary Work and Research

- How Sahagún Did His Research

- Why Sahagún's Work is Important

- Sahagún as a Franciscan Friar

- Concerns About Conversions

- Sahagún's Stories of the Conquest

- Works by Bernardino de Sahagún

- Images for kids

- See also

Early Life and Education in Spain

Bernardino de Rivera was born in 1499 in Sahagún, Spain. He went to the University of Salamanca. There, he learned about new ideas from the Renaissance. This university was a key place for Franciscan thinkers in Spain. It was here that he joined the Order of Friars Minor, also known as the Franciscans. He likely became a priest around 1527. When he joined the order, he changed his last name to the name of his hometown, becoming Bernardino de Sahagún.

Spanish conquerors led by Hernán Cortés took over the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City) in 1521. Franciscan missionaries arrived soon after in 1524. Sahagún was not in this first group. However, because of his strong academic and religious background, he was asked to join the missionary effort in New Spain in 1529. He would spend the next 61 years there.

Missionary Work in New Spain

During the Age of Discovery (from 1450 to 1700), Spanish rulers were very interested in teaching Christianity to the native people in newly found lands. In Spain, the king and queen helped fund this missionary work. This was part of their plan to conquer and settle new lands.

After the Spanish conquest, the native culture changed a lot. This change included a strong religious side, which helped create the unique Mexican culture we know today. People from both Spanish and native cultures had many different ideas about these changes.

The Franciscans, along with other religious groups, led the effort to establish the Catholic Church in New Spain. Many Franciscans were excited about the new land and its people. They believed that teaching the Christian message to these new people was very important. They thought it could even lead to the return of Christ. Many friars were also unhappy with problems in Europe, including within the Church. They saw New Spain as a chance to bring back the pure spirit of early Christianity.

In the first years after the conquest, many native people became Christian, at least on the surface. The friars hired many natives to build churches and monasteries. These natives also worked as artists, painters, and sculptors. They decorated the churches with their art. Native artists often added symbols from their own customs and beliefs, like flowers, birds, or geometric shapes. The friars thought these were just decorations. But the natives knew they had deep religious meanings. This mix of Christian and native symbols is called Indochristian art.

At first, the plan to spread Christianity seemed very successful. Hundreds of thousands of native people were baptized. However, the native people did not always practice Christianity in the way the friars expected. Many still followed their old religious rituals and beliefs, even while taking part in Catholic worship. The friars disagreed on how to handle this problem.

At the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco

Sahagún helped start the first European-style school of higher education in the Americas. This was the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco in 1536, in what is now Mexico City. This school later became a base for his research. He hired his former students to help him. The college helped blend Spanish and native cultures in Mexico.

The school helped teach students about Christianity. It also trained native men to become Catholic priests. It was a center for studying native languages, especially Nahuatl. Sahagún taught Latin and other subjects there in the early years. Other friars taught grammar, history, and philosophy. Native leaders were also hired to teach about native history and traditions. This caused some concern among Spanish officials who wanted to control the native populations.

Sahagún was one of several friars at the school who wrote important accounts of native life and culture. Two famous works from the college are the first New World "herbal" and a map of the Mexico City area. An "herbal" is a book about plants and their uses, including medicines. The Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis was an herbal written in Latin by Juan Badiano, an Aztec teacher at the college. It showed drawings of plants and described how to use them for medicine. The Mapa de Santa Cruz showed cities, roads, canals, and activities like fishing and farming. Both the herbal and the map show how Spanish and Aztec cultures mixed.

Sahagún's Missionary Work and Research

Besides teaching, Sahagún spent time outside Mexico City. He worked in places like Tlalmanalco and Xochimilco. He was first and foremost a missionary. His main goal was to bring the people of the New World to the Catholic faith. He spent a lot of time with native people in small villages, working as a priest, teacher, and missionary.

Sahagún was very good at languages, like many Franciscans. The Franciscans believed in teaching native people in their own languages. Sahagún started learning Nahuatl while sailing across the Atlantic. He learned from native nobles who were returning to New Spain from Spain. He became one of the best Spanish speakers of Nahuatl. Most of his writings were meant to help churchmen preach in Nahuatl. He also wanted to help them translate the Bible or teach Christianity to native people. He translated the Psalms and wrote a catechism in Nahuatl.

Sahagún was curious to learn about the Aztec worldview. His language skills helped him do this. He studied the people and their culture. He did his research in Nahuatl. In 1547, he collected huehuetlatolli, which means "Words of the old men." These were formal speeches given by Aztec elders for moral lessons and education. Between 1553 and 1555, he interviewed native leaders to hear their side of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. In 1585, he wrote a new version of the conquest story. This became Book 12 of the Florentine Codex.

How Sahagún Did His Research

After the first wave of conversions in Mexico slowed down, Franciscan missionaries realized they needed to understand native people better. In 1558, a new leader of the Franciscans in New Spain, Fray Francisco de Toral, asked Sahagún to write about topics useful for missionary work in Nahuatl. The leader wanted Sahagún to organize his studies of native language and culture so others could learn from it. Sahagún was given freedom to do his research. He spent about 25 years gathering information and another 15 years editing and translating it.

From his early research, Sahagún wrote a text called Primeros Memoriales. This book became the foundation for his larger Historia general. He did his research in Tepeapulco, about 50 miles northeast of Mexico City. There, he spent two years interviewing about a dozen village elders in Nahuatl. Native graduates from the college at Tlatelolco helped him.

Sahagún asked the elders about their religious rituals, calendar, family life, economy, and natural history. He interviewed them alone and in groups. This way, he could check if the information was reliable. His assistants spoke three languages: Nahuatl, Latin, and Spanish. They helped with research, translation, and drawing illustrations. Sahagún even wrote down their names and gave them credit for their work. The pictures in the Primeros Memoriales show a mix of native and European art styles. Sahagún was always improving his ways of gathering and checking information.

Later, from 1561 to 1575, Sahagún returned to Tlatelolco. He interviewed more elders and cultural experts. He edited his earlier work and made his research even broader. He organized his project like the medieval encyclopedias of his time. These were like "worldbooks" that tried to present a complete picture of knowledge.

Why Sahagún's Work is Important

Sahagún was one of the first to create ways to gather and confirm knowledge about native cultures in the New World. Much later, the science of anthropology would use similar methods, called ethnography. This is a scientific way to document the beliefs, behaviors, and way of life of another culture. Sahagún's methods were an early form of modern ethnography.

He gathered information from many different people, including women, who were known for their knowledge of native culture. He compared the answers from different sources. Some parts of his writings seem to be direct notes from what people told him. Other parts show that he asked specific questions to different people to get information on certain topics. Some parts are Sahagún's own stories or comments.

During Sahagún's research, the Spanish conquerors were greatly outnumbered by the Aztecs. The Spanish worried about a native uprising. Some Spanish officials thought his writings were dangerous. They felt his work gave too much importance to native voices and ideas. Sahagún knew he had to be careful to avoid trouble with the Inquisition, which was set up in Mexico in 1570.

Sahagún's work was first written only in Nahuatl. To avoid suspicion, he translated parts into Spanish. He showed it to other Franciscans and sent it to the King of Spain. His last years were hard. The early hopes of the Franciscans in New Spain were fading. The Spanish rule continued to be harsh. Millions of native people died from diseases brought by Europeans. Some of his last writings show sadness. The King also reduced the role of religious orders like the Franciscans. In 1575, the Council of the Indies banned all scriptures in native languages. They forced Sahagún to hand over all his documents about Aztec culture. They might have seen studying local traditions as a problem for the Christian mission. Despite this ban, Sahagún made two more copies of his Historia general.

Sahagún's Historia general was not known outside Spain for about 200 years. In 1793, it was found in a library in Florence, Italy. Today, historians, anthropologists, and linguists still study Sahagún's work.

The Historia general is one of the most amazing social science projects ever done. It is special because Sahagún tried to learn about a foreign culture by interviewing people and getting their own views. As one scholar said, "the scope of the Historia’s coverage of contact-period Central Mexico indigenous culture is remarkable, unmatched by any other sixteenth-century works." Even though Sahagún saw himself as a missionary, scholars call him the "father of American Ethnography."

Sahagún as a Franciscan Friar

Sahagún has been called a missionary, a cultural researcher, a linguist, and a historian. These roles came from his identity as a missionary priest. He was part of the Spanish effort to convert new peoples. He was also part of the larger Franciscan goal to spread Christianity.

The Franciscan Friars were started by Francis of Assisi in the early 1200s. They focused on the human side of Jesus Christ. Saint Francis believed in caring for the poor and those who were left out of society. Franciscan prayer includes remembering Jesus' human life and helping those in need.

This way of thinking influenced Sahagún. He believed that native peoples had dignity and deserved respect as human beings. The friars were often upset by how the Spanish conquerors treated the native people. Sahagún worked with native people and gave them credit for their help. This shows the Franciscan value of community.

In his five decades of research, he put his Franciscan beliefs into action. He didn't just guess about these new people. He met with them, interviewed them, and tried to understand their world. While others in Europe were arguing if native people were truly human and had souls, Sahagún was talking to them. He wanted to understand who they were, what they believed, and how they made sense of the world. Even though he disagreed with some of their practices, he spent 50 years studying Aztec culture. His main goal was to help them become Christian.

Concerns About Conversions

As Sahagún learned more about Aztec culture, he became unsure about how deep the mass conversions to Christianity really were. He thought that many conversions were only on the surface. He also worried that his fellow Franciscan missionaries did not understand basic parts of traditional Aztec religious beliefs. He became convinced that missionaries could only be effective if they truly understood native languages and worldviews. So, he began to study native peoples, their beliefs, and their religious practices in detail.

In the Florentine Codex, Sahagún wrote many introductions and notes where he shared his own views in Spanish. In one section, he wrote about mountains and rocks. He used this to describe old religious practices that were still happening among the people. He said, "Having discussed the springs, waters, and mountains, this seemed to me to be the opportune place to discuss the principal idolatries which were practiced and are still practiced in the waters and mountains."

In this section, Sahagún also expressed his deep doubt that the Christian faith would last in New Spain. This was especially true after a terrible plague in 1576 killed many native people.

Sahagún's Stories of the Conquest

Sahagún wrote two versions of the conquest of the Aztec Empire. The first is Book 12 of the General History (written in 1576). The second is a revised version finished in 1585. The 1576 version tells the story only from the native, mostly Tlatelolcan, point of view.

He changed the story in 1585. In this version, he added parts praising the Spanish, especially the conqueror Hernán Cortés. This was different from his earlier version, which stuck to the native viewpoint. The original 1585 manuscript is lost, but a copy was found later. Sahagún said that the history of the conquest was a tool for friars to learn the language of warfare. Telling the conquest story from the defeated Aztecs' point of view could be risky for the Spanish crown. So, Sahagún might have been careful about how his history was seen. His 1585 revision, which praised Cortés and the Spanish conquest, was made when work on native texts was being criticized. Sahagún likely wrote this version keeping that political situation in mind.

Works by Bernardino de Sahagún

- Coloquios y Doctrina Christiana (Conversations and Christian Doctrine) – This book describes discussions between the first twelve Franciscan friars and native leaders.

- The Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain – A huge 12-volume work translated into English.

- The Conquest of New Spain, 1585 Revision.

- Primeros Memoriales (First Memorials) – An early work that led to the Historia general.

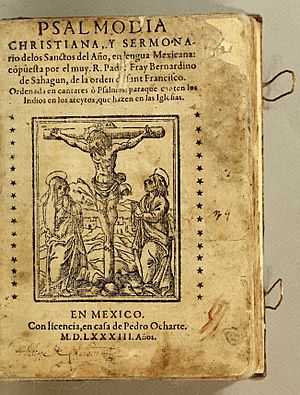

- Psalmodia Christiana (Christian Psalms) (1583) – A book of Christian songs and poems in Nahuatl.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Bernardino de Sahagún para niños

In Spanish: Bernardino de Sahagún para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |