Aztec codex facts for kids

Aztec codices (also called Mēxihcatl āmoxtli in Nahuatl) are ancient manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztecs and their descendants. These special books were created during the colonial period in Mexico.

Contents

What are Aztec Codices?

Before the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Mexica people and their neighbors used painted books. These books helped them record many parts of their lives. They contained information about history, science, land ownership, taxes (tribute), and religious ceremonies.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a Spanish soldier, said that Moctezuma had a large library of these books. They were called amatl or amoxtli. A nobleman kept them in the palace. Even after the Spanish arrived, native people kept making these painted manuscripts. The Spanish even used them as important records. This tradition of drawing and writing continued for many years after the Europeans came. The last known examples are from the early 1600s.

How Were Aztec Codices Made?

Since the 1800s, the word codex has been used for all Mesoamerican picture books. However, Aztec manuscripts were not always shaped like modern books. They were often made from long sheets of paper from fig bark (amate) or stretched deerskins. These pieces were sewn together to make long, narrow strips. Some were even painted on large cloths.

Common shapes included screenfold books (like an accordion), strips called tiras, rolls, and cloths called lienzos. We don't have any Aztec codices with their original covers. But from other similar books, we think they might have had wooden covers. These covers might have been decorated with beautiful turquoise designs.

How Did Aztecs Write and Draw?

Aztec codices are different from European books because most of their content is pictures. Experts have different ideas about whether parts of these books are "writing." Some think they mix pictures with true writing. Others see them as a system of pictures that sometimes include symbols for sounds.

However, everyone agrees that most information in these books was shown through images. Writing was mostly used for names.

What Did Aztec Art Look Like?

The art style of Aztec pictures before the Spanish arrived was similar to the Mixtec people. This is because the art of tlacuilolli (manuscript painting) was brought to the Aztec ancestors by groups from the Mixtec lands.

The Mixtec style used a "frame line" to outline areas of color. Colors were usually put inside these lines without any shading. Human figures were often shown in separate parts. Buildings were not realistic but followed certain rules. There was no 3D look or perspective.

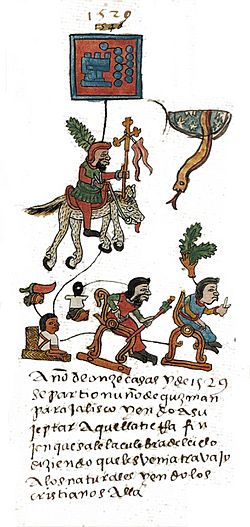

After the Spanish arrived, codices started to look different. They used European-style outlines and tried to show 3D shapes and perspective. Later, experts defined a special Aztec style. It was a bit more natural and used unique calendar symbols.

Different Art Schools

Experts have found three main art styles or "schools" within the Aztec pictorial tradition:

- School of Mexico Tenochtitlan: This style came from the capital city, Tenochtitlan. Early examples include the Matrícula de Tributos and Codex Boturini. Later examples are the Codex Mendoza and Codex Telleriano-Remensis.

- School of Texcoco: This school was based in the city of Texcoco. It includes documents related to the court of Nezahualcoyotl. Important works are the Mapa Quinatzin and Codex Xolotl.

- School of Tlatelolco: This school was from Tlatelolco, a city near Tenochtitlan. It is linked to the Badianus herbal and the Florentine Codex.

Saving Aztec Codices

Many ancient and colonial native texts have been lost or destroyed. When Hernán Cortés arrived in 1519, the Aztecs had books in temples and palaces. For example, the soldier Juan Cano described books in Moctezuma's library about religion, family histories, government, and geography. He regretted that the Spanish destroyed them, as they were vital for native nations.

Catholic priests also destroyed many surviving manuscripts. They burned them because they thought the books were against their religion.

However, many manuscripts did survive! They are now in museums, archives, and private collections. Scholars have studied them a lot. A big project in the 1970s published a guide to Mesoamerican pictorial manuscripts. It included many pictures from the Valley of Mexico.

Are Any Codices Pre-Hispanic?

Three Aztec codices might be from before the Spanish arrived: Codex Borbonicus, the Matrícula de Tributos, and the Codex Boturini. Some experts think they show small signs of European influence. For example, the Codex Borbonicus seems to have space left for Spanish notes. The Matrícula de Tributos uses paper sizes similar to European paper.

However, other experts disagree. They believe these codices are truly pre-Hispanic. So, whether these manuscripts are from before the conquest is still debated.

Types of Information in Codices

The information in these manuscripts falls into several groups:

- Calendars: Showing dates and cycles.

- History: Recording past events.

- Family Trees: Showing important family lines.

- Maps: Showing land and places.

- Economy/Tribute: Listing taxes paid.

- Economy/Census: Counting people and property.

- Property Plans: Showing land boundaries.

A list of 434 Mesoamerican pictorial manuscripts gives details about each one. It includes their title, where they are, their history, and what they show.

Some native texts called Techialoyan manuscripts are written on native paper (amatl). They usually describe meetings of native leaders and the boundaries of their towns. Another type of colonial-era religious text is called Testerian manuscripts. These are catechisms (religious instruction books) with prayers and memory aids.

There are also some codices that were intentionally faked. A scholar named John B. Glass made a list of these.

Another source of information is the Relaciones geográficas from the late 1500s. These were reports about native settlements in colonial Mexico, ordered by the Spanish crown. Each report was supposed to include a picture of the town, often drawn by a native resident. Even though these were made for Spanish use, they have important information about native history and geography.

Important Aztec Codices

Some very important colonial-era codices have been published with English translations:

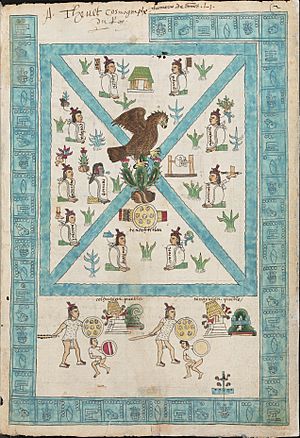

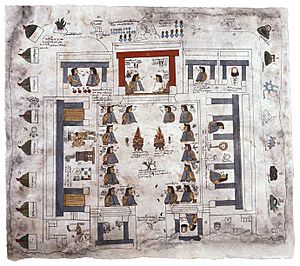

- Codex Mendoza: This book mixes pictures with Spanish notes. It has three parts: a history of Aztec rulers and their conquests, a list of taxes paid by different areas, and a general description of daily Aztec life. It is kept at the Bodleian Library in England.

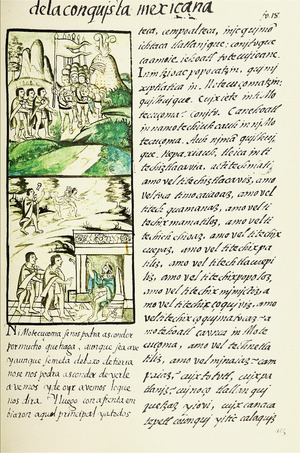

- Florentine Codex: This huge project was led by a friar named Bernardino de Sahagún. He worked with native people to record their knowledge of Aztec religion, society, and nature. It also includes a history of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire from the Mexica point of view. This project resulted in 12 books with both Nahuatl and Spanish text, plus illustrations by native artists.

- Works by Diego Durán: This Dominican friar used native pictures and talked to native people to create illustrated books on history and religion.

Colonial-era codices often have Aztec pictures or other visual elements. Some are written in Classical Nahuatl (using the Latin alphabet) or Spanish, and sometimes Latin. A few are entirely in Nahuatl with no pictures.

Even though few pre-Hispanic codices survived, the tlacuilo (codex painter) tradition continued. Today, scholars have about 500 colonial-era codices to study.

Some written manuscripts in the native tradition also have pictures, like the Florentine Codex and Codex Mendoza. But others are only text in Spanish or Nahuatl.

List of Aztec Codices

- Anales de Tlatelolco: An early colonial-era history written in Nahuatl, with no pictures. It tells about Tlatelolco's role in the Spanish conquest.

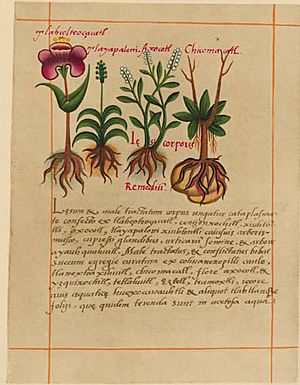

- Badianus Herbal Manuscript: This book describes the medicinal uses of plants by the Aztecs. It was translated into Latin in 1552 from a Nahuatl original.

- Codex Azcatitlan: A picture history of the Aztec empire, including images of the conquest.

- Codex Aubin: A picture history of the Aztecs from their journey from Aztlán to the early colonial period (ending in 1608). It includes a native description of the Massacre in the Great Temple in 1520.

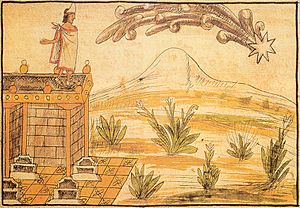

- Codex Borbonicus: Written by Aztec priests, likely after the Spanish conquest. It was originally all pictures. It has three parts: a calendar for telling the future, a record of the 52-year cycle, and rituals.

- Codex Borgia: A pre-Hispanic ritual codex, named after Cardinal Stefano Borgia.

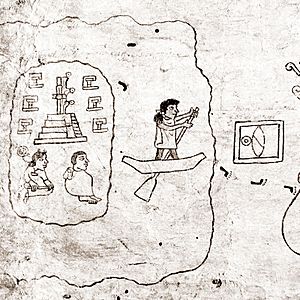

- Codex Boturini (or Tira de la Peregrinación): Painted between 1530 and 1541. It tells the story of the Aztec journey from Aztlán to the Valley of Mexico. It's a long sheet of fig bark paper, folded like an accordion. The drawings are outlines in black ink, not colored.

- Codex Cozcatzin: A post-conquest manuscript from 1572. It has pictures with short descriptions in Spanish and Nahuatl. It lists land given by Itzcóatl and historical information about Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlan.

- Codex Fejérváry-Mayer: A pre-Hispanic calendar codex.

- Codex Ixtlilxochitl: An early 1600s fragment describing Aztec festivals and rituals. Each of the 18 months is shown with a god or historical figure.

- Codex Magliabechiano: Created in the mid-1500s. It's mainly a religious document, showing day names, monthly feasts, deities, and beliefs.

- Codex Mexicanus

- Codex Osuna: A mix of pictures and Nahuatl text, detailing complaints from native people against colonial officials.

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis: A calendar, divining almanac, and history of the Aztec people.

- Codex Ríos: An Italian translation and addition to the Codex Telleriano-Remensis.

- Codex of Tlatelolco: A picture codex made around 1560.

- Codex Vaticanus B

- Codex Vergara: Records the sizes of Mesoamerican farms and calculates their areas.

- Codex Xolotl: A picture codex telling the history of the Valley of Mexico, especially Texcoco.

- Codex Florentine: A set of 12 books created between 1540 and 1576. It's a main source of information about Aztec life before the Spanish conquest.

- Huexotzinco Codex: Nahua pictures that were part of a 1531 lawsuit.

- Mapa de Cuauhtinchan No. 2: A post-conquest native map, showing land rights.

- Mapa Quinatzin: A 16th-century mix of pictures and text about the history of Texcoco. It has information on their legal system, showing crimes and punishments.

- Oztoticpac Lands Map of Texcoco, 1540: A picture on native paper from Texcoco about a land estate.

- Santa Cruz Map: A mid-16th-century picture of the central lake system area.

Why Codices are Still Important Today

Studying these codices continues to be very important in modern Mexico. Especially for today's Nahuas, who are reading these texts to learn about their own history. Research on these codices is also growing in Los Angeles, where there is more interest in the Nahua language and culture.

See also

In Spanish: Códices mexicas para niños

In Spanish: Códices mexicas para niños

- Codex Zouche-Nuttall - one of the Mixtec codices.

- Crónica X

- Historia de Mexico with the Tovar calendar, ca. 1830–1862. From the Jay I Kislak Collection at the Library of Congress

- Maya codices

- Mesoamerican literature

- Colonial Mesoamerican native-language texts