Codex Azcatitlan facts for kids

The Codex Azcatitlan is an Aztec codex (an ancient book of pictures) that tells the story of the Mexica people. It covers their long journey from their homeland, Aztlán, all the way to the time when the Spanish arrived and conquered Mexico. We don't know the exact year this codex was made, but experts think it was created between the mid-1500s and the 1600s. The name "Codex Azcatitlan" was suggested by an early researcher, Robert H. Barlow. He thought a picture of an anthill on page 2 meant "Aztlán." Today, this important book is kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.

Contents

What Makes It Special?

The Codex Azcatitlan is unique because it mixes traditional Mesoamerican art with European Renaissance art styles. A Mexican historian named Federico Navarrete noticed that it uses European ways to show things, like making objects look three-dimensional. The main artist, called a tlacuilo, also made images overlap to create a sense of depth, just like in European paintings. The people in the codex also look like they are moving more than in older Aztec books.

How It Was Made

The codex was put together using both Aztec and European methods. It has 25 pages, called leaves, made from European paper. Each page is about 21 centimeters (8.3 inches) high and 28 centimeters (11 inches) wide. The pictures flow across the pages. If a scene runs out of space, the last image is drawn again at the start of the next page. Some pages seem to be missing because this flow isn't always perfect. The book also looks unfinished in some parts, with colors missing and draft lines still visible.

This codex was created by two artists: a master and an apprentice. The master artist planned the whole story and painted the more difficult and important parts. The master followed traditional Mesoamerican art rules. For example, his human figures are almost always shown from the side, with sharp-angled faces looking to the right. The apprentice's figures, however, use more curved lines and shadows to make bodies look more realistic. He even drew a character looking directly at the viewer on one page, which was unusual. The master used strong, complete lines and colors for his figures and symbols.

It's possible that one or both of these artists knew Antonio Valeriano, who was a governor in Tenochtitlan from 1573 to 1599. They might have also studied at a famous school called the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco.

The master artist seemed to draw all the Aztec calendar year symbols (like Reed, Flint, House, Rabbit) in one go. This is suggested by how similar they look in shape, even if their colors are sometimes different. After drawing these, he added the corresponding years from the Julian calendar.

The apprentice artist's work first appears on page 6v, where houses are shaded in his style. He then took over completely until page 12r, which is when the Mexica people arrived at Tenochtitlan.

History of the Codex

We don't know exactly when the Codex Azcatitlan was created. Historian María Castañeda de la Paz thinks it was written in the second half of the 1500s. The notes written in Nahuatl (the Aztec language) suggest a date in the late 1500s. However, these notes might have been added later by someone who didn't fully understand the original drawings.

At one point, the codex belonged to a nobleman named Lorenzo Boturini Benaduci in the 1700s. Later, it became part of collections in France, including those of Joseph Marius Alexis Aubin and Eugène Goupil. When Goupil died in 1898, the codex was given to the Bibliothèque Nationale. Out of the original 28 pages, three are now missing. In 1995, a color copy of the codex was made available to the public.

The first detailed study of the Codex Azcatitlan was done by R. H. Barlow in the mid-1900s. He suggested that two artists made the book. Later, another historian, Donald Robertson, questioned some of Barlow's ideas about which artist did which parts.

What's Inside the Codex?

The Codex Azcatitlan is divided into four main parts. It tells the story of the Mexica people from their journey out of Aztlán up to about 1527, shortly after the death of Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec emperor.

The first part is like a diary of the Mexica's migration from Aztlán. It highlights the role of the Tlatelolca Mexica, showing them as equally important as the Tenochca Mexica. This was a big deal because after 1473, the ruling Tenochca Mexica tried to hide the importance of the Tlatelolca Mexica. The second part tells the history of the Aztec Empire, showing the reigns of each of its rulers, called tlatoani, across two-page spreads.

The third part describes the Spanish Conquest. It breaks away from the usual style of showing dates and places, focusing only on the events themselves. This section is thought to have originally had four two-page spreads, including the fourth section. The final part shows early colonial Mexican history, arranged in vertical columns.

Notes written in Nahuatl appear mostly in the migration section. They help explain places and characters. Sometimes, they also translate the year symbols for readers who weren't familiar with old Aztec writing. These notes appear less often in the empire section and then disappear completely.

The Migration Story

Unlike older Aztec books, this codex shows many details of the migration. It depicts stops at fresh water, times when they got lost, building temples, and even attacks by wild animals. The artists recorded every year of the journey, grouping years to show how long they stayed in each place. The way Aztlán is shown in the codex really emphasizes the Tlatelolca's role in Mexica history. The island city is drawn as two parts, similar to Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco. It also has four "house" symbols, which refer to Tenochtitlan's four neighborhoods.

The first page (folio 1 recto) shows the three rulers of the Triple Alliance. They are sitting on European-style thrones, wearing native clothes, and holding staffs of office. The migration begins on the next page (folio 1 verso). It shows the Azteca leaving their island homeland, Aztlán, as commanded by their god, Huitzilopochtli. He appears nearby as a warrior with a hummingbird headdress. Also on this page is a symbol of an ant surrounded by dots. Above it is the note "Ascatitla," which gave the codex its name. A horn comes out of this symbol, which is another hint about Tlatelolco.

Guided by a dark-skinned priest, the Azteca cross into the land of Colhuacan. There, they talk among themselves and with Huitzilopochtli. They also meet eight other tribes who want to join them on their journey. The Azteca agree, and the nine tribes set off. They are led by four "god-bearers," each carrying a sacred bundle.

On page 4v, the codex shows the first sacrifices made by the Azteca to Huitzilopochtli. He then names them the Mexica and gives them a bow, arrow, fire-starting tool, and a basket.

The Azteca stop at Coatlicamac for two years on page 5v. The migration story ends on page 6r with the Mexica arriving and staying at Coatepec for nine years.

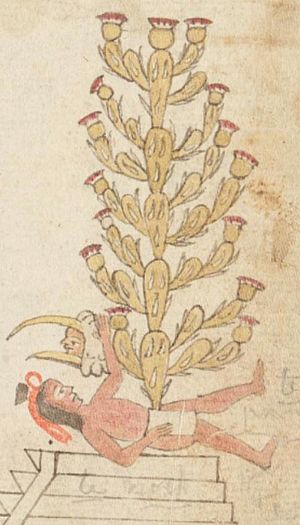

On page 12r, the heart of a person named Copil is sacrificed to Huitzilopochtli. From this sacrifice grows the nopal cactus, which marks the land Huitzilopochtli promised to the Mexica. The migration part ends on the next page with the founding of Tenochtitlan (left; 12v) and Tlatelolco (13r). It also shows the selection of their first rulers. Six men fishing and hunting in Lake Texcoco separate the two founding scenes.

The Imperial Story

The Imperial section is similar to other Aztec codices of that time, like the Aubin Codex and Mendoza Codex. It records the actions of the rulers of Tenochtitlan as a series of events, moving from left to right, without any dates. This section is not finished. For example, some ruler portraits are incomplete. Three notes, the last ones in the codex, appear on pages 13v to 15r. They explain some parts of Tepanec history, like the crowning and death of Maxtla of Azcapotzalco. Most of these two-page spreads end with the mummy of the ruler.

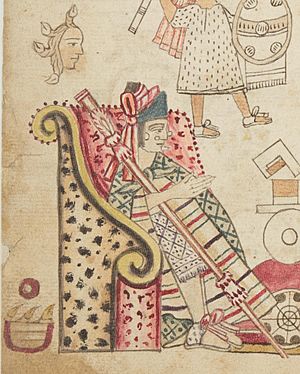

This section begins on page 13v with a nopal cactus, which represents Tenochtitlan. To its right is Acamapichtli, Tenochtitlan's first ruler. This pattern repeats for each ruler who followed. The first symbol to Acamapichtli's right is for Colhuacan, his home city. Above it is the head of Huitzilopochtli. Next, the codex shows three conquests by the Mexica for Azcapotzalco. After these, a palace or temple is built in Tlatelolco, where Cuacuapitzauac and three relatives appear. In the middle of the spread, Tezozomoc dies and is replaced by Maxtla. The codex also shows how the Mexica developed ways to get food from Lake Texcoco. Finally, Acamapichtli's mummy appears on the far right of the spread.

The pictures of Acamapichtli (13v) and Axayacatl (18v) are the only fully painted portraits in this section. The master artist painted Acamapichtli, and the apprentice painted Axayacatl.

The Conquest Story

The Conquest section is also incomplete and has no dates or notes. It focuses on the brave actions of a Tlatelolca warrior named Ecatl, also known as Don Martín. This section tells a story similar to other native accounts of the Conquest, like those found in the Florentine Codex. The master artist of the Azcatitlan Codex made sure to show native victories and minimize their defeats. This section originally had four two-page spreads, but two have been lost.

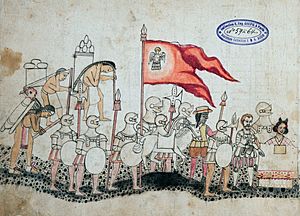

The section begins on page 22v with Hernán Cortés and La Malinche meeting another group. Behind Cortés stands his army, shown as eight Spanish soldiers, an African slave, a horse, and three native men carrying supplies. Malinche is translating for him. We don't know who she is talking to because the next page is missing. However, it's likely this scene shows Cortés meeting Moctezuma II outside Tenochtitlan on November 8, 1519.

Next is page 23r, which is the right half of a spread showing the Toxcatl massacre of 1520, ordered by Pedro de Alvarado. The Templo Mayor (Great Temple) takes up the right side of the page, and a European-style building is at the top. This part of the codex shows both the massacre and the city's uprising against the Spanish that followed.

On the left side of page 23v, there is a Spanish ship and six armored Spaniards in the water in front of it. A native man pulls a Spaniard out, while another fights a Mexica warrior armed with a Spanish sword. The fighting Spaniard holds a shield with a sun image. This person is thought to be Alvarado, who the Mexica called "Tonatiuh" (Sun). The scene shows a failed attack in May 1521 led by Alvarado. Cortés almost got captured while trying to save drowning Spaniards. Cortés is believed to be the Spaniard being pulled from the water by the native man. The Mexica warrior fighting Alvarado is Ecatl. He led Tlatelolco's warriors against the Spanish and once captured a banner from Alvarado. Ecatl is special because of the wavy pattern on his tunic, which is similar to the waters around Aztlán and Tenochtitlan when the Mexica first arrived. His shield also looks like Huitzilopochtli's shield on page 1v, with a symbol that refers to Huitzilopochtli's rule as the Fifth Sun. All these signs show Ecatl as a holy warrior of Huitzilopochtli.

Page 24r shows the evacuation of Cuauhtemoc's wife, Tecuichpotzin, from Tenochtitlan on August 31, 1521, after the city surrendered. Three boats, each with a woman, sail at the bottom of the page. Above them, five more women stand on top of some buildings. Their clothes show they are wealthy, and the woman on the far right might be Tecuichpotzin.

After the Conquest

Pages 24v to 25r change the usual story flow. They present their content in two vertical columns per page.

This section begins on page 24v with a pile of bones, representing the destruction of Tenochtitlan. Next, the important people of Tlatelolco are shown leaving the city to live under Spanish rule. This is shown below a symbol for Amaxac, where Cuauhtemoc surrendered. This was also where the city's people left after the surrender in August 1521. Four native rulers sit below, representing Cuauhtemoc, Coanacoch of Texcoco, Tetlepanquetzal of Tlacopan, and Temilotl of Tlatelolco.

Next, the start of Christianization in the 1520s is shown by a vertical line of nine friars (religious brothers). A tenth friar is baptizing an indigenous man. Above and between the nine priests is a palo volador dance with four dancers and a musician on top of the pole. Following the priests are images (like a digging stick, wood, water) that symbolize the rebuilding of Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco as Mexico City under Tlacotl. His name is shown by a hand grasping an animal's head. Above the construction is a picture of a battle at Colhuacan.

The right half of page 24v and all of page 25r tell about events from 1524 to 1526. This content relates to Hernán Cortés's trip to Honduras and his killing of Cuauhtemoc, who was supposedly plotting against Cortés. The left side of page 24r shows the expedition, while the right side concerns events back in the former Aztec Empire.

The time of Cuauhtemoc's death is marked by the artist in the upper-right corner of page 24v. While Cortés was in Honduras, a power struggle happened between the man he left in charge, Alonso de Estrada, and two of his other men. Estrada arrested them and executed their supporters, as shown at the bottom left.

The last existing page of Codex Azcatitlan, folio 25v, records the arrival of Mexico's first bishop, Julián Garcés.

|

See also

In Spanish: Códice Azcatitlan para niños

In Spanish: Códice Azcatitlan para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |