Templo Mayor facts for kids

Aerial image of the Templo Mayor

|

|

| Alternative name | Huey Teocalli |

|---|---|

| Location | Mexico City, Mexico |

| Coordinates | 19°25′59.88″N 99°7′58.008″W / 19.4333000°N 99.13278000°W |

| History | |

| Periods | Late Postclassic |

| Cultures | Aztec |

| Site notes | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Mexico City and Xochimilco |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, iv, v |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Area | 3,010.86 ha |

The Templo Mayor (which means Main Temple in English) was a very important temple for the Mexica people. They lived in their capital city, Tenōchtitlan, which is now Mexico City. This amazing building was built in a style from the late Postclassic period. In the Nahuatl language, it was called Huēyi Teōcalli.

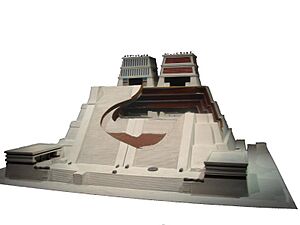

The temple honored two main gods at the same time. One was Huitzilopochtli, the god of war. The other was Tlaloc, the god of rain and farming. Each god had its own special shrine at the top of the pyramid. They even had separate staircases leading up to them! A central spire was also dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, in his form as Ehecatl, the wind god. The base of this grand temple was about 100 by 80 meters. It was the most important building in the Sacred Precinct. Builders started the first temple after 1325. Over time, it was rebuilt six more times, each new temple built over the last. Sadly, the Spanish almost completely destroyed the temple in 1521. The Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral was later built nearby.

Today, the Zócalo, Mexico City's main plaza, is southwest of where the Templo Mayor once stood. The temple's ruins are located between Seminario and Justo Sierra streets. This area is part of the Historic Center of Mexico City. It became a UNESCO World Heritage List site in 1987. In 2017, over 800,000 people visited this incredible historical site.

Contents

Discovering the Templo Mayor

The Ancient City of Tenochtitlan

After the Spanish conquered Tenōchtitlan, the Templo Mayor was taken apart. Its stones were used to build the new Spanish colonial city. Because of this, people forgot the temple's exact location for a long time. By the 20th century, experts had a good idea where to look. This was thanks to archaeological work done in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Finding the Lost Temple

In the late 1800s, Leopoldo Batres dug near the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral. At first, people thought the cathedral was built right on top of the temple. Later, it was found to be just southwest of the temple. In the early 1900s, Manuel Gamio found part of the temple's southwest corner. His discoveries were shown to the public. However, there wasn't much interest in digging more at that time. The area was a fancy neighborhood. Over the next few decades, other archaeologists found small parts of the temple. These included staircases, beams, and platforms with serpent heads.

Uncovering History: The Templo Mayor Project

The big breakthrough happened on February 21, 1978. Workers for the city's electricity company, CFE, were digging. They were in an area known as the "island of the dogs." This spot was a bit higher, so stray dogs gathered there during floods. About two meters down, the diggers hit a huge stone disk. It was over 3.25 meters wide, 30 centimeters thick, and weighed 8.5 tons!

This amazing stone carving showed Coyolxauhqui, the sister of the god Huitzilopochtli. It was made in the late 1400s. This discovery sparked huge excitement. From 1978 to 1982, archaeologists led by Eduardo Matos Moctezuma began a major project. They worked to uncover the entire temple. Many artifacts were in great condition for study. The Templo Mayor Project was officially approved by the government.

To dig up the site, 13 buildings in the area had to be taken down. These included some from the 1930s and some older ones from the 1800s. During the excavations, over 7,000 objects were found. These included statues, clay pots shaped like Tlaloc, and skeletons of animals like turtles, frogs, and fish. They also found snail shells, coral, gold, alabaster, and masks. Many of these treasures are now in the Templo Mayor Museum. This museum helps everyone learn about the temple and its history.

Layers of History: How the Temple Grew

The Templo Mayor site has two main parts. One part is the temple itself, showing its different building stages. The other part is the museum, which holds smaller and more delicate objects. The Aztecs often expanded their temples by building new structures right over the old ones. This made the older temple a strong base for the new, larger one. The Aztecs started building the Templo Mayor after 1325. They rebuilt it six times in total. Archaeologists have found and studied all seven stages of the temple, except for the very first one. Each stage is linked to the Aztec emperors who ordered its construction.

The First Temple: A Humble Beginning

We only know about the first temple from old historical writings. This is because the ground where it was built is very wet. It was once part of a lakebed. This makes it hard to dig down to the very first layer. Records say the first pyramid was made of earth and wood. These materials might not have lasted until today.

Building Up: Temples Two to Six

Temple Two: Early Discoveries

The second temple was built between 1375 and 1427. This was during the time of emperors Acamapichtli, Huitzilihuitl, and Chimalpopoca. Archaeologists have uncovered the top part of this temple. They found two stone shrines covered in stucco on the north side. They also found a chacmool, which is a special type of statue. On the south side, there was a stone for ceremonies called a téchcatl and a carved face.

Temple Three: Guarded Stairways

The third temple was built between 1427 and 1440. This happened during the reign of Emperor Itzcoatl. From this stage, we have a staircase with eight stone figures. These figures are like "divine warriors" guarding the path to the shrines above. They have a symbol showing the year Four-Reed (1431).

Temple Four: Rich Decorations

The fourth temple was built between 1440 and 1481. This was during the reigns of emperors Moctezuma I and Axayacatl. This stage is known for its beautiful decorations and sculptures. Many of the amazing things found during excavations come from this time. The large platform was decorated with serpents and special containers for burning incense. Some of these containers were shaped like monkeys or the god Tlaloc. The stairway to Tlaloc's shrine had wavy serpents on its sides. In the middle of this shrine was a small altar with two sculpted frogs. The famous round stone disk of Coyolxauhqui also dates from this period.

Temple Five: A Fresh Look

The fifth temple was built between 1481 and 1486. This was during the short reign of Emperor Tizoc. In these five years, the platform was covered with a smooth stucco finish. The ceremonial plaza was also paved.

Temple Six: Grand Additions

The sixth temple was built during the reign of Emperor Ahuizotl. He completed some of Tizoc's updates and added his own. This is shown on a special stone carving. It depicts two emperors celebrating the temple's opening in 1487. A wall decorated with serpent heads was built around the Sacred Precinct. Ahuizotl also built three shrines and the House of the Eagle Warriors.

The Grand Seventh Temple

Very little of the Seventh Temple remains today. This is because it was torn down to build the cathedral. We can only see a platform to the north and some paving in the courtyard. Most of what we know about this temple comes from historical records. It was the largest and most important ceremonial center of its time. A friar named Bernardino de Sahagún wrote that the Sacred Precinct had 78 buildings. The Templo Mayor stood tall above them all.

The pyramid had four sloped levels with paths between them. A large platform topped the pyramid. Two stairways led up to the two shrines on this platform. The shrine on the left was for Tlaloc, the water god. The shrine on the right was for Huitzilopochtli, the god of the sun and war. Both temples were about 60 meters tall, including the pyramid. Each had large containers where sacred fires burned all the time. Statues of strong, seated men stood at the entrance to each temple. They held up banners made of bark paper. The stairways had railings with fierce serpent heads at the bottom. Only priests and people involved in special ceremonies used these stairs. The entire building was once covered in stucco and brightly painted.

Inside the temples, statues of the gods were kept behind curtains. The figure of Huitzilopochtli was made from amaranth seeds and honey. Inside it were bags with jade, bones, and amulets. This figure was made new each year. It was richly dressed and wore a gold mask for its festival. After the festival, parts of the image were shared among the people.

The Temple's Final Days

When the Spanish arrived in 1519, they were amazed by the many grand temples in Tenōchtitlan. However, they did not agree with the Aztec beliefs. On November 14, 1519, Cortés captured Emperor Moctezuma II. He ordered the destruction of Aztec religious items. Cortés also had a Catholic cross placed on the Templo Mayor.

After the fall of Tenōchtitlan in 1521, the Aztec lands became part of the Spanish empire. All the temples, including the Templo Mayor, were searched for gold and other precious materials. Cortés ordered a new city built in the Spanish style. The important parts of the old Aztec center, like the Templo Mayor, were buried. They lay beneath the new city, which is now downtown Mexico City. The Templo Mayor and its Sacred Precinct were torn down. A Spanish church, which later became the main cathedral, was built on the western part of the precinct.

Understanding the Temple's Meaning

A Sacred Place: The Eagle and the Cactus

According to Aztec stories, the Templo Mayor stands on a very special spot. This is where the god Huitzilopochtli showed the Mexica people their promised land. The sign was an eagle perched on a nopal cactus, holding a snake in its mouth. This image is now on the Mexican flag!

Connecting Worlds: Aztec Cosmology

The different levels of the Temple also showed how the Aztecs saw the universe. It was lined up with the main directions (north, south, east, west). Gates connected to roads going in these directions. This showed where the human world met the thirteen levels of the heavens (Topan) and the nine levels of the underworld (Mictlan).

Archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma explained that the temple's direction showed the Mexica's view of the universe. He said the Templo Mayor was the "main center" where all parts of the universe met. It was a place where "all sacred power is concentrated." This idea is linked to the myth of Huitzilopochtli and Coyolxauhqui.

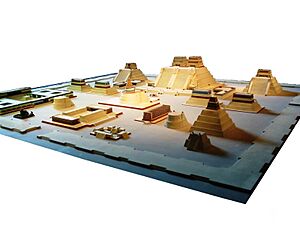

Exploring the Sacred Precinct

The Serpent Wall and Important Buildings

A wall called the "coatepantli" (serpent wall) surrounded the Sacred Precinct of the Templo Mayor. Inside this area were many important buildings. These included the ballcourt, the Calmecac (a school for priests), and temples for gods like Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca, and the sun. The Templo Mayor itself formed the eastern side of this sacred area.

Home of the Eagle Warriors

Archaeologists found several rooms and buildings next to the Templo Mayor. One of the best preserved is the Palace (or House) of the Eagle Warriors. This area dates back to the temple's fourth stage, around 1469. It was excavated in the early 1980s. It's a large L-shaped room with staircases decorated with eagle head sculptures. To enter, you passed between two large statues of these warriors. The Eagle Warriors were a special group dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. They dressed to look like eagles. Next to this palace is their temple, also known as the Red Temple. Its paintings, mostly red, and altar design show influences from Teotihuacan.

The inside walls of the House of the Eagles have beautiful paintings and long, painted benches. These benches have two parts. The top part shows wavy serpents carved in relief. The bottom part shows warriors marching towards a zacatapayolli. This was a grass ball used in certain ceremonies. Many important artifacts were found here. The most notable are two large ceramic sculptures of Mictlantecuhtl, the god of death. They were carefully put back together and are now in the museum.

Another area was for the Ocelot Warriors. Their temple, dedicated to the god Tezcatlipoca, is under the current Museo de la Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público.

Schools and Temples for Other Gods

The Calmecac was a living area for priests. It was also a school for future priests, leaders, and politicians. They studied subjects like theology, literature, history, and astronomy there. Its exact location is near what is now Donceles Street. The Temple of Quetzalcoatl was west of the Templo Mayor. It is said that on certain days, the sun rose between the shrines of Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc and shone directly on this temple. Because Quetzalcoatl was often shown as a serpent, his temple had a round base instead of a square one.

The Ancient Ballgame and Skull Rack

The ball field, called the tlachtli or teutlachtli, was like many sacred ball fields in Mesoamerica. Players used their hips to move a heavy ball towards stone rings. The field was west of the Templo Mayor, near the twin staircases. Next to this ball field was the "huey tzompanti," a structure where skulls were displayed.

The Temple of the Sun was also west of the Templo Mayor. Its remains are under the Metropolitan Cathedral. Work to support the cathedral in the late 1900s and early 2000s uncovered many artifacts.

Treasures and Offerings

Gifts for the Gods

Most of the objects found at the Templo Mayor were offerings. Many were made by the Mexica, but there were also many items from other groups. These were brought in as gifts or through trade. Sculptures, flint knives, pots, beads, and other fancy ornaments were found. Minerals, plants, and animals of all kinds were also placed as offerings. Each item had a special meaning in the offering.

Archaeologists found different types of offerings. They studied when and where each offering was placed. They also looked at the type of container and how objects were arranged inside. Offerings were usually placed in hidden spots. These included cavities, stone urns, and boxes made of stone slabs. They were found under floors, in platforms, stairways, and temples. These offerings were part of complex rituals.

The oldest Mexica objects, found in the second temple, are two urns. They contained the remains of burned bones. One urn was made of obsidian, and the other of alabaster. A small silver mask and a gold bell were in one urn. Another gold bell and two green stone beads were in the other.

Symbols of Fire and Water

Statues of the gods Huehueteotl-Xiuhtecuhtli and Tlaloc were often found in the offerings. Huehueteotl-Xiuhtecuhtli represented fire, and Tlaloc represented water. Together, they likely symbolized "burning water," which was a metaphor for warfare.

Other ceremonial items found include musical instruments, jewelry, and containers for burning copal (a type of incense).

The Templo Mayor Museum

The Templo Mayor Museum opened in 1987. It was built to house the finds from the Templo Mayor Project. This project is still ongoing today! In 1991, the Urban Archaeology Program joined the project. Its goal is to dig in the oldest parts of the city, around the main plaza. Architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez designed the museum building. He wanted it to blend in with the old colonial buildings around it.

The museum has four floors. Three floors are for permanent exhibits. The fourth floor has offices for the director and research staff. Other departments and an auditorium are in the basement.

Exploring the Museum's Halls

The museum has eight main exhibition halls, each with a different theme.

- Room 1 is about the goddesses Coatlicue and Coyolxauhqui. Coatlicue was Huitzilopochtli's mother, and Coyolxauhqui was his sister. This room shows the first finds from the temple. It includes the huge stone disk of Coyolxauhqui, which started the whole Templo Mayor Project.

- Room 2 explores rituals and offerings in Tenōchtitlan. It has urns where important people were buried and special items given to the gods.

- Room 3 shows how the Aztec empire worked economically. It displays items brought as tribute or through trade from different parts of Mesoamerica.

- Room 4 is dedicated to the god Huitzilopochtli. His shrine at the temple was the most important. This room has various images of him and offerings. It also holds the two large ceramic statues of Mictlantecuhtli found in the House of the Eagle Warriors.

- Room 5 is for Tlaloc, another main Aztec god and one of the oldest in Mesoamerica. This room has many images of Tlaloc, often made from green or volcanic stone, or ceramic. A prized item is a large pot with Tlaloc's face, still showing much of its original blue paint.

- Room 6 focuses on the plants and animals of Mesoamerica. Many of these had special meanings for the Aztecs. Also, many offerings found at the Templo Mayor were made from plants and animals.

- Room 7 is related to Room 6. It shows the farming technology of the time. This includes how corn was grown and how chinampas (floating gardens) were built.

- Room 8 is the last room. It tells the story of the site's archaeology and history.

See also

In Spanish: Templo Mayor para niños

In Spanish: Templo Mayor para niños

- List of Mesoamerican pyramids

- Massacre in the Great Temple

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century