La Malinche facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marina

|

|

|---|---|

Malintzin, in an engraving dated 1885.

|

|

| Born | c. 1500 |

| Died | before February 1529 (aged 28–29) |

| Other names | Malintzin, La Malinche |

| Occupation | Interpreter, advisor, intermediary |

| Known for | Role in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire |

| Spouse(s) | Juan Jaramillo |

| Children | Martín Cortés María |

Marina (around 1500 – around 1529), often called La Malinche or Malintzin, was a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast. She played a very important role in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–1521). She worked as an interpreter, advisor, and helper for the Spanish leader Hernán Cortés.

In 1519, she was one of 20 enslaved women given to the Spanish by the native people of Tabasco. Cortés chose her as his partner. Later, she gave birth to his first son, Martín. He was one of the first Mestizos in New Spain. Mestizos are people with both European and Indigenous American family backgrounds.

Over time, people's opinions about La Malinche have changed. After Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821, some stories and paintings showed her as a bad or tricky person. But today in Mexico, La Malinche is a powerful symbol. She is seen as a mother figure for the new Mexican people. The word malinchista is sometimes used in Mexico to describe someone who seems to prefer foreign things over their own culture.

Contents

Who Was La Malinche?

Her Many Names

Malinche is known by several names. The Spanish baptized her as a Catholic and named her "Marina." They often called her "Doña Marina," using a special title for noblewomen. The Nahua people called her 'Malintzin'. This name came from 'Malina' (her Spanish name in Nahuatl) and the special ending '-tzin'.

Her birth name is not known. For a long time, people thought her first name was 'Malinalli', which means 'grass' in Nahuatl. They thought she was named after a day sign in the Aztec calendar. However, modern historians do not believe this. They say that the Nahua people usually avoided using 'Malinalli' as a name because it had bad meanings.

She was also sometimes called 'Tenepal'. This name likely came from Nahuatl words meaning "one who speaks well" or "one who has a way with words." So, 'Malintzin Tenepal' might have meant something like "Doña Marina the interpreter" in Spanish.

Early Life and Languages

Malinche was likely born around the year 1500. She came from a noble family in a place near the Aztec Empire. Even though many people in her hometown spoke Popoluca, her family probably spoke Nahuatl. She also seemed to understand a special, polite form of Nahuatl used by nobles. The Spanish often called her "Doña," which shows they saw her as important.

When she was young, probably between 8 and 12 years old, she was either sold or taken as a slave. She was taken to Xicalango, a big port city. Later, she was bought by a group of Chontal Maya people. They brought her to the town of Potonchán. Here, Malinche learned the Chontal Maya language. She might have also learned Yucatec Maya. This was very important later because she could then talk with Gerónimo de Aguilar, another Spanish interpreter who spoke Yucatec Maya and Spanish.

Helping Cortés Conquer Mexico

When Cortés first arrived in Mexico, he fought with the Maya people at Potonchán. After the battle, the Maya offered gifts to the Spanish, including twenty enslaved women. Malinche was one of these women. The Spanish baptized the women and gave them to Cortés's men to be servants. Malinche was given to Alonso Hernández Puertocarrero, one of Cortés's captains.

First Meetings and Alliances

The Spanish soon discovered Malinche's amazing language skills. When they met Nahuatl-speaking people, Cortés's other interpreter, Aguilar, could not understand them. Cortés realized Malinche could speak with them. He promised her freedom and more if she helped him talk to Moctezuma, the Aztec emperor. Cortés then took Malinche to be his main interpreter.

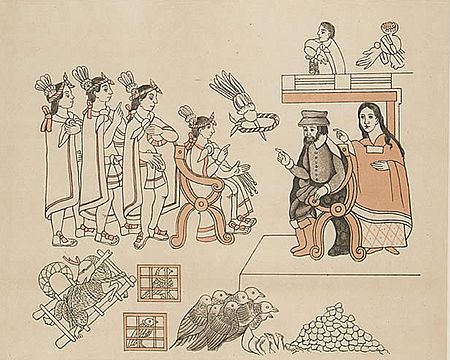

With Aguilar and Malinche, Cortés could now talk to Moctezuma's messengers. The messengers even drew pictures of Malinche, Cortés, and their ships to send back to Moctezuma. People later said that the Nahua sometimes called Cortés "Malinche," showing how important she was to the Spanish group.

From then on, Malinche worked with Aguilar to help the Spanish and Nahua communicate. Cortés would speak Spanish to Aguilar, who translated it into Yucatec Maya for Malinche. Malinche then translated it into Nahuatl. This process was reversed for answers. Sometimes, the translation chain was even longer if another language, like Totonac, was involved. It's amazing that they could communicate at all!

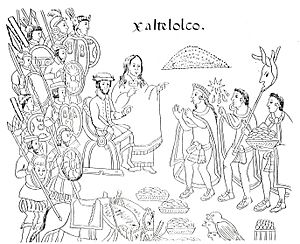

Meeting the Totonac people was how the Spanish first learned about groups who were against Moctezuma. The Spanish made an alliance with the Totonac and prepared to march towards Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital.

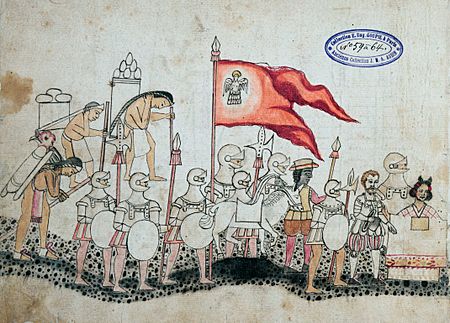

The Cholula Event

On their way to Tenochtitlan, the Spanish met the Tlaxcaltec people. At first, the Tlaxcaltec fought the Spanish. But later, they made an alliance through Malinche and Aguilar. Tlaxcalan drawings from that time show Malinche as a very important person, helping the two sides talk.

After staying in Tlaxcala, Cortés and a large group of Tlaxcalan soldiers went to Cholula. The Spanish claimed that the people of Cholula were planning a secret attack against them. Stories say that Malinche found out about this plot. She supposedly pretended to join a Cholulan noblewoman who offered her a marriage. This way, Malinche learned the details of the plan and told Cortés.

This story has sometimes been used to say Malinche "betrayed" her people. However, modern historians think this story might have been made up by Cortés. He may have wanted a reason to attack Cholula and make his actions seem fair to the Spanish leaders back home. Historians believe Cortés and the Tlaxcalans worked together. The Tlaxcalans saw the attack on Cholula as a test of the Spanish commitment to their alliance.

Meeting Moctezuma

In November 1519, the Spanish and their allies reached Tenochtitlan. Moctezuma met them on a causeway leading to the city. Malinche was right there, translating the conversation between Cortés and Moctezuma. Some records suggest she had already learned some Spanish and was translating directly.

Moctezuma's speech was very polite and formal. The Spanish later claimed it meant he was giving up his power. But modern historians disagree. Moctezuma used a special, respectful form of Nahuatl. It's possible that some of the meaning was lost in translation, or that the Spanish misunderstood his words on purpose.

Life After the Conquest

Tenochtitlán fell in late 1521. Marina's son with Cortés, Martín Cortés, was born in 1522. Marina lived in a house Cortés built for her near Mexico City.

From 1524 to 1526, Cortés took Marina with him to help stop a rebellion in Honduras. She again worked as an interpreter. While there, she married Juan Jaramillo, a Spanish nobleman. Historians believe she died sometime before February 1529. She had a son, Martín, who was raised mostly by his father's family. She also had a daughter, María, who was raised by Jaramillo and his second wife.

Even though Martín was Cortés's first son, Spanish historians didn't write much about his mother, Marina. But many scholars believe that her child with Cortés was the start of the large mestizo population in Mexico.

Why Was She So Important?

Having a good interpreter was very important for the Spanish. But Marina's role was even bigger. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, a soldier who wrote about the conquest, often spoke highly of "Doña Marina." He said, "Without the help of Doña Marina, we would not have understood the language of New Spain and Mexico." Another soldier, Rodríguez de Ocaña, said Cortés believed Marina was the main reason for his success, after God.

Indigenous drawings and writings also show how important she was. Even though some people today see her as a traitor, the Tlaxcalan people did not. In some pictures, she is shown as larger than Cortés, wearing rich clothes. She is shown making alliances between the Tlaxcalan and the Spanish. They respected and trusted her.

In the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, Cortés is rarely shown without Marina beside him. Sometimes, she is even shown alone, seeming to lead events herself. If she had been trained for noble life, as Díaz said, her role might have been like a noble wife. A Nahua wife gained through an alliance would help her husband with military and diplomatic goals.

Today, historians praise Marina's diplomatic skills. Some even think of her as "the real conqueror of Mexico." Old Spanish soldiers remembered that one of her best skills was convincing other native groups that it was useless to fight against Spanish weapons and ships. After Marina started helping Cortés, the Spanish had to fight much less often.

Without La Malinche's language skills, communication between the Spanish and the Indigenous peoples would have been much harder. La Malinche knew how to speak in different ways to different tribes and social classes. When speaking to Nahua audiences, she used formal and powerful language. This made the Nahua think she was a noblewoman who knew what she was talking about.

La Malinche Today

La Malinche has become a legendary figure in Latin American art and culture. She is seen in many ways. Some people see her as a founding mother of the Mexican nation. Others still see her as a traitor.

In the 1960s, feminist thinkers began to look at Malinche differently. They saw her not as a traitor, but as a victim. Mexican feminists defended Malinche as a woman caught between different cultures. She had to make difficult choices, and in the end, she became a mother of a new mixed race.

Today in Mexican Spanish, the words malinchismo and malinchista are used to describe Mexicans who seem to prefer foreign culture over their own.

Some historians believe La Malinche helped save her people from the Aztecs, who controlled many lands and demanded payments from other groups. Some Mexicans also credit her with bringing Christianity to the New World. They believe she influenced Cortés to be more kind. However, others argue that without her help, Cortés would not have conquered the Aztecs so quickly. This would have given the Aztec people more time to learn about new weapons and fighting methods. From this view, she is seen as someone who betrayed the Indigenous people by siding with the Spanish. Recently, some feminist Latinas have said that blaming her is unfair.

A sculpture of Cortés, Doña Marina, and their son Martín was made and placed in Mexico City. But because of protests, it was later moved to a less noticeable park.

See also

In Spanish: La Malinche para niños

In Spanish: La Malinche para niños