Danza de los Voladores facts for kids

The Danza de los Voladores (meaning "Dance of the Flyers") is an ancient ceremony from Mesoamerica. It is also called Palo Volador ("flying pole"). This ritual is still performed today in parts of Mexico. It is believed to have started with the Nahua, Huastec, and Otomi peoples in central Mexico. From there, it spread across much of Mesoamerica.

The ritual involves dancing and climbing a pole about 30-meter (98 ft 5 in) tall. Four of the five participants then launch themselves from the top. They are tied with ropes and slowly descend to the ground. The fifth person stays on top of the pole, dancing and playing a flute and drum. One old story says the ritual began to ask the gods to end a severe drought. While the ritual did not start with the Totonac people, it is now strongly linked to them. This is especially true for those living near Papantla in Veracruz, Mexico. UNESCO named the ceremony an Intangible cultural heritage. This helps keep the ritual alive and strong in the modern world.

Contents

History of the Flying Pole Dance

According to a Totonac story, about 450 years ago, there was a terrible drought. This drought caused a lot of hunger. People believed the gods were holding back the rain because they felt forgotten. So, the ceremony was created to please the gods and bring back the rain.

In some versions of the story, wise old men created the ritual. They chose five young men who were pure. In other versions, the five young men themselves created it. They would cut down the tallest tree in the forest. They asked permission from the mountain god first. Then, they removed its branches and brought it to the village. The tree trunk was set up with a special ceremony. The young men climbed the pole. Four of them jumped off, while the fifth played music. This ritual pleased the rain god Xipe Totec and other gods. The rains returned, and the earth became fertile again.

The exact start of this ritual is not fully known. It is thought to have begun with the Huastec, Nahua, and Otomi peoples. This was in the Sierra de Puebla and mountain areas of Veracruz. The ritual spread widely in Mesoamerica. It was practiced from northern Mexico all the way to Nicaragua. Ancient pottery from Nayarit shows evidence of the ritual from a very long time ago.

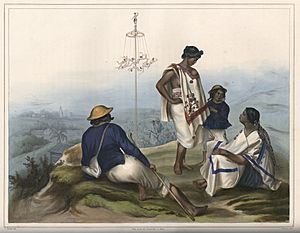

In ancient times, the ritual was much more complex. It involved special rules and meditation. The participants were thought to act like birds. In some areas, they dressed as parrots, macaws, quetzals, and eagles. These birds represented the gods of earth, air, fire, and water. By the 16th century, the ritual was strongly linked to sun ceremonies. An example is the spring equinox. The ritual is most closely connected with rain and sun gods.

In Maya mythology, the world's creation is linked to a bird god. This god lived at the World Tree, which was the center of the world. Five "birdmen" at the top of a pole represent bird gods. The main dancer plays a flute, sounding like birds singing. The four other "birdmen" spin around the pole. This represents the world being created again and life being renewed.

Diego Durán wrote about Aztec customs during the Spanish conquest. He described an event similar to the Danza de los Voladores. An Aztec prince, Ezhuahuacatl, sacrificed himself by diving from a tall pole. Today, the four voladores usually circle the pole 13 times each. This makes a total of 52 circles. This number is important because it matches the number of years in the Aztec "calendar round".

The ritual was partly lost after the Spanish conquest. Many records about it were destroyed. However, Juan de Torquemada kept a detailed account. The Church was against "pagan" rituals after the Conquest. This and many other rituals were stopped or done in secret. Much of what we know comes from oral stories and early European writings. Later, Catholic elements were added to the ritual. It became a public show in the colonial period. The ritual mostly disappeared in Mexico and Central America. Only small parts survived, especially with the Totonac people.

Even though the ritual did not start with the Totonacs, it is now often linked to them. This is true for the Totonacs in the Papantla area of Veracruz. In modern times, some things have changed. Many forests have been cut down. So, most voladores now perform on permanent metal poles. In Veracruz, oil companies often donate these poles.

A big change has been allowing women to perform the ceremony. Traditionally, it was forbidden for women to be voladores. But a few women in Puebla state have become voladores. One of the first men to train women, Jesús Arroyo Cerón, died. He fell from a pole during a festival in 2006. Totonac elders believe this was a punishment from the gods. They still do not allow women to perform the ritual.

Different Ways the Ritual is Performed

There are different ways the Voladores ritual is performed. Among the Nahua and Otomi peoples, there is usually no dance before climbing the pole. The ceremony starts at the top. There is also a version where the platform has five sides instead of four. This version involves six dancers, not five. This version is often performed on Holy Thursday. Some dancers follow special rules. For example, they might fast for a day or more before the ceremony. This is to make sure the gods look kindly on the ritual. Most of these different versions are found in Puebla state.

The most debated difference is whether women should be allowed to perform. In Papantla, the Totonac elders have officially said no to women. Traditionally, women have been kept out of all Totonac ritual dances. This is because of a belief that women are "bad entities" who bring bad luck. They believe allowing women would be a sin or make the gods angry.

However, in some communities, women are allowed to be voladores. These include Cuetzalan and Pahuatlán in Puebla, and Zozocolco de Hidalgo in Veracruz. Women who take part must first complete special rituals. These rituals ask for forgiveness from the gods and Catholic saints for being a woman.

It is not known when the first woman was allowed to be a volador. Jesús Arroyo Cerón trained his daughter Isabel in 1972. He later trained his other three daughters. In March 2006, he fell from a pole and died. He was 70 years old. His family believes he died "at the side of the gods." But many traditional leaders believe it was a punishment from the gods. A wooden cross and flowers remember him at the Plaza del Volador. About twenty female voladores are known to exist.

In Guatemala, the flying pole dance is called Palo volador. It is still celebrated in Joyabaj, Chichicastenango, and Cubulco.

The Totonac Version

According to Totonac stories, the gods told men, "Dance, and we shall observe." Today, pleasing the old gods is still a key part of the most traditional ritual. The Totonac costume for this ritual includes red pants and a white shirt. They wear a cloth across the chest and a special cap. The pants, hat, and chest cloth are richly embroidered and decorated. The cloth across the chest represents blood. The hat has flowers for fertility. Mirrors on the hat represent the sun. Colorful ribbons stream from the top, representing the rainbow. The voladores make these costumes themselves.

The most traditional and longest version starts with choosing and cutting the tree. It ends with a final dance after all voladores have come down. The tree selection, cutting, and setting up ceremony is called the tsakáe kiki. It involves going into the forest to find a suitable tree. They ask permission or forgiveness from the mountain god Quihuicolo for taking it. The tree is stripped of its branches. Then, it is dragged to the ceremony site. A hole is dug for the 30-meter pole. Before setting up the pole, offerings are placed in the hole. These include flowers, copal, candles, and live chickens or a turkey. These are then crushed as the pole is set up. This adds to the earth's fertility. The pole becomes a link between the sky, the earth, and the underworld. It represents the world tree. It is seen as the fifth main direction of the earth. The pole and dancers are then purified with alcohol and tobacco smoke.

However, in most cases today, a permanent pole is used. These are often made of steel. So, this part of the ceremony does not happen. In these cases, the ceremony begins with a dance and song called a "son." The first song is usually the "son of forgiveness." After this, the five voladores begin to climb the pole. The leader, or "caporal," goes first. The caporal does not come down until near the end of the ceremony. The caporal stands on a small platform at the top of the pole. This platform is called a manzana (apple). A square frame, called a cuadro (square), hangs from this platform. The other four voladores sit on this frame.

While these four wrap ropes around the pole and tie themselves, the caporal plays the flute and drum. He acknowledges the four main directions, starting with the east. This is because life is believed to come from the east. Each of the four ropes is wound thirteen times. This makes a total of fifty-two windings. This number matches the years in a Mesoamerican great year. The caporal then bends fully backward to honor the sun, playing music all the while.

The four voladores represent the four main directions. They also represent the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. The caporal represents the fifth sun. The four voladores sit on the cuadro facing the caporal. At the right moment, they fall backward to descend. They are suspended by the ropes. As the ropes unwind, the voladores spin. They create a moving pyramid shape. As the other voladores descend, the caporal plays the "son of goodbye." He dances on the narrow platform. Traditionally, after the descent, there is another goodbye dance.

Keeping the Tradition Alive: UNESCO and Conservation

The Ritual Ceremony of the Voladores of Papantla was recognized by UNESCO in 2009. It was named an Intangible cultural heritage (ICH). This was the second Mexican event to get this honor. The first was the Indigenous Festivity of the Dead in 2008. Governor Fidel Herrera Beltrán accepted the award. He received it for the people and government of Veracruz. Special thanks went to the indigenous people of the Totonacapan region. Celebrations for this recognition happened on October 12, 2009. They took place at Takilhsukut Park in El Tajín and other volador sites in Mexico.

This recognition means Mexico has a responsibility to protect and promote the tradition. This helps keep it alive. Part of the nomination process included a big plan. This plan aimed to preserve, promote, and develop the cultural heritage in Veracruz and other parts of Mexico and Central America.

One effort is the Escuela de Niños Voladores (School of Volador Children). It is located at Takilhsukut Park. This is the first formal school for voladores. It has between 70 and 100 students. They learn about the history, meaning, and values of the ritual. This includes the ancient ways of taking the pole from the forest. This part of the ritual is in danger of disappearing. The Veracruz state government supports the school. Children start attending between 6 and 8 years old. Most come from nearby communities. Their fathers and grandfathers are often voladores. The school has rules for students. For example, they must speak Totonac, and girls are not allowed. However, most voladores learn the ritual from their fathers and grandfathers. They start learning around age eight or ten. Becoming a volador in the traditional Totonac community takes 10 to 12 years of training. Many see it as a lifelong calling.

Another effort to save and promote the tradition is the Encuentro de Voladores (Volador Encounter). This event started in 2009. It happens during the Cumbre Tajín spring equinox festival at the El Tajín site. For five days, voladores from different places perform at the poles there. The goal is to see different costumes and styles. It is also a chance to share experiences about the fertility ritual. Voladores come from places as far as San Luis Potosí and Guatemala.

One reason for needing protection is that in most parts of Mexico, the ritual is not performed for religious reasons. The first organization for voladores started in the 1970s. This also led to the ritual becoming more commercial. There are about 600 professional voladores in Mexico.

In smaller communities, the ritual is only performed on special feast days. These are usually for the community's patron saint or other religious events. But in bigger communities, especially where there are tourists, it is performed to get donations. For example, voladores perform in Xcaret and Xel-Ha. Totonac voladores in Chapultepec Park in Mexico City are a major attraction. Some groups try to balance respecting the ritual with performing for spectators. There is a formal group in Boca del Río. Local authorities recognize them and give them a space and a permanent pole. This group aims to offer tourists a respectful version of the ritual. They perform at Plaza Bandera and do not forget their roots. All members of the group are from Papantla. The ceremony is held in a public park. Young people are asked to leave items like bicycles and skateboards outside the ceremonial area.

To promote the ritual and its culture internationally, voladores groups have performed in many places. They have performed in Mexico and other countries as part of cultural festivals. Voladores have performed at the Zapopum Festival in Guadalajara, the Festival of San Pedro in Monterrey, the Indian Summer Festival in Milwaukee, the Carnaval Cultural in Valparaíso, the Forúm Universal de las Culturas in Barcelona, and at a show in New York.

In Popular Culture

- In episode 6 of the animated series Onyx Equinox, characters visit the Totonac city of Tajin. People there perform the dance, and can even grow bird wings and fly.

- During the song "Without Question" from the Dreamworks animated film The Road to El Dorado, Miguel takes part in the ritual.

See also

In Spanish: Rito de los voladores para niños

In Spanish: Rito de los voladores para niños