El Tajín facts for kids

|

|

| Location | Veracruz, Mexico |

|---|---|

| Region | Veracruz |

| Coordinates | 20°26′53.01″N 97°22′41.67″W / 20.4480583°N 97.3782417°W |

| History | |

| Periods | Early Classic to Late Postclassic |

| Cultures | Classic Veracruz |

| Site notes | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | El Tajin, Pre-Hispanic City |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, iv |

| Inscription | 1992 (16th Session) |

| Area | 240 ha |

El Tajín is an amazing ancient city in southern Mexico. It was one of the biggest and most important cities in Mesoamerica during its Classic era. This city was part of the Classic Veracruz culture.

El Tajín thrived from about 600 to 1200 AD. During this time, people built many temples, palaces, ballcourts, and pyramids. After the city fell around 1230, it was hidden by the jungle for over 500 years. No one in Europe knew about it until 1785!

The name El Tajín comes from the Totonac rain god. In 1992, it became a World Heritage Site because of its unique buildings and cultural importance. Its architecture features special decorative niches and a type of cement not seen elsewhere in Mesoamerica.

The most famous building is the Pyramid of the Niches. Other important spots include the Arroyo Group and the palaces of Tajín Chico. So far, 20 ballcourts have been found here. El Tajín is a top tourist spot in Veracruz, attracting many visitors each year.

It also hosts the annual Cumbre Tajín Festival in March. This festival celebrates local and international cultures with music and events.

Contents

Where is El Tajín Located?

The ancient city is in the highlands of Papantla, Veracruz, Mexico. It's not far from the city of Poza Rica. The city sits among low mountains that lead to the Gulf coast.

In ancient times, El Tajín controlled a large area. This area stretched between the Cazones and Tecolutla Rivers. Two streams flow through the main city, providing fresh water. Most of the big buildings are where these streams meet.

The area is a rainforest with a hot, wet climate. The average temperature is around 35°C (95°F). Hurricanes can happen from June to October. Cold winds from the north, called "nortes," also affect the region. Today, the land around El Tajín has tobacco fields, banana plantations, and vanilla groves.

What Does the Name El Tajín Mean?

When El Tajín was rediscovered in 1785, local Totonac people knew it by that name. They said it meant "of thunder or lightning bolt." They believed that twelve old thunderstorm gods, called Tajín, still lived in the ruins.

However, some old maps from the Spanish conquest suggest another name. These maps, called the Lienzos de Tuxpan, hint that the city might have been called "Mictlan." This means "place of the dead." This was a common name for ancient sites whose original names were forgotten. Another Totonac meaning for El Tajín is "place of the invisible beings or spirits."

The Story of El Tajín City

Studies show that people have lived in this area since at least 5600 BCE. Nomadic hunters slowly became farmers and built more complex societies. This happened faster when the nearby Olmec civilization grew around 1150 BCE.

It's not fully clear who built El Tajín. Some think it was the Totonacs or Xapaneca people. Others believe the Huastec lived here when the city started in the 1st century CE. Big buildings began to appear soon after. By 600 CE, El Tajín was a thriving city.

El Tajín grew quickly because it was on important trade routes. It controlled goods like vanilla being sent out and items from other parts of Mesoamerica coming in. Many objects from Teotihuacan have been found here.

El Tajín's Golden Age (600-1200 CE)

From 600 to 1200 CE, El Tajín was a rich and powerful city. It controlled much of what is now Veracruz state. The city was well-organized, with over fifty different groups of people living there. Most people lived in the hills around the main city.

The city got most of its food from nearby farming areas. These farms grew corn, beans, and luxury items like cacao. A carving on the Pyramid of the Niches even shows a ceremony at a cacao tree.

Religion in El Tajín focused on the planets, stars, Sun, and Moon. The Mesoamerican ballgame and a drink called pulque were very important. This led to the building of many pyramids with temples and seventeen ballcourts. That's more than any other Mesoamerican site!

El Tajín's influence spread widely. You can see its unique niche designs in buildings at nearby sites like Yohualichan. Its reach extended along the Gulf coast to the Maya region and into central Mexico.

El Tajín survived the collapse that affected many other cities at the end of the Classic period. It reached its peak after the fall of Teotihuacan. The city kept many traditions from that civilization. Its greatest time was from 900-1100 CE.

The Fall of El Tajín

El Tajín thrived until the early 1200s. Around 1230, it was destroyed by fire. Historians believe invaders, possibly the Chichimecs, caused this destruction. After El Tajín fell, the Totonacs built a new settlement nearby called Papantla.

El Tajín was left to the jungle and stayed hidden for over 500 years. Even though the city was covered, local people likely never completely forgot it. Archeological finds show a village existed here when the Spanish arrived. The Totonacs have always considered the area sacred. However, no European records mention the site before the late 1700s.

How El Tajín Was Rediscovered

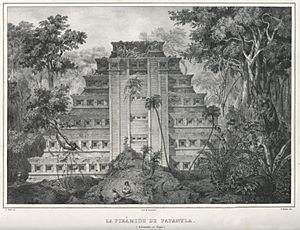

In 1785, a government official named Diego Ruiz found the Pyramid of the Niches. He was looking for illegal tobacco farms in the remote area. He drew the pyramid and reported his discovery. Ruiz said the local people had kept the place a secret.

His report sparked interest in Mexico and Europe. Scholars like José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez and Ciriaco Gonazlez Carvajal wrote about it. They even compared the pyramid to buildings in ancient Rome. Alexander von Humboldt and Pietro Márquez also helped spread the word about the pyramid in Europe.

Since its rediscovery, El Tajín has attracted visitors for two centuries. In 1831, German architect Charles Nebel visited. He was the first to draw and describe the Pyramid of the Niches and other ruins in detail. He also guessed that the pyramid was part of a larger city. His drawings were published in a book in Paris in 1836.

The first archeologists arrived in the early 1900s. They included Teobert Maler and Edward Seler. Oil discoveries in the area led to better roads from the 1920s to the 1940s. This allowed for more detailed studies of the site.

From 1935 to 1938, Agustin Garcia Vega did the first official mapping and clearing. He uncovered more buildings and suggested calling it "The Archeological City of El Tajín." The Pyramid of the Niches was the first building fully cleared of jungle.

Starting in 1938, Jose Garcia Payon led excavations and reconstruction for 39 years. He uncovered platforms, ballcourts, and parts of Tajín Chico. By the 1970s, El Tajín was a major tourist attraction in Veracruz. From 1984 to 1994, Jürgen K. Brüggemann found 35 more buildings. It's believed that only about half of El Tajín has been uncovered so far.

El Tajín: A World Heritage Site

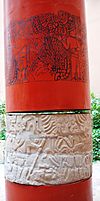

El Tajín became a World Heritage Site in 1992. This was because of its important history, architecture, and engineering. Its unique architecture features detailed carvings on columns and walls. The Pyramid of the Niches is a masterpiece. It shows how important astronomy and symbols were in their buildings. El Tajín is one of Mexico's most important ancient sites.

The city's size and unique art make it special. The full size of the residential areas is still unknown. However, the entire site is estimated to be about 2,640 acres (10.68 square kilometers). Only about half of the city's buildings have been dug up. These reveal plazas, palaces, and government buildings. Unlike other ancient cities with strict grid patterns, El Tajín's buildings were designed as individual units.

Several architectural features are unique to El Tajín. Decorative niches and stepped frets are everywhere. They even decorate supporting walls. Stepped frets are seen elsewhere in Mesoamerica, but not as much as here. The use of niches is truly special to El Tajín.

Unique Building Methods

One special thing about El Tajín's buildings is the use of poured cement. Surviving roof pieces from Building C in Tajín Chico show this. These cement roofs were very thick to support themselves without beams. To make them lighter, pumice stones and pottery shards were mixed into the cement. The cement was poured in layers. It's thought that buildings were filled with earth to support the roof while it dried. The finished roofs were almost a meter thick and very flat. This kind of cement roof was unique in ancient Mesoamerica.

Poured cement was also used in Building B, the only two-story building at the site. It formed both the roof and the floor between levels. Two-story buildings are rare, found only in Mayan areas. Another feature shared with the Mayans is the use of light blue paint. Many homes in El Tajín also had windows to let in cool breezes on hot days. This was another unique design.

The Many Ballcourts

While ballcourts are common in Mesoamerica, El Tajín stands out with seventeen of them. Two ballcourts have carved panels showing the ball game and its ritual meaning. The South Ballcourt's panels are especially impressive. They show underworld gods and a ballplayer being sacrificed. This sacrifice was to ask the gods for pulque for his people.

Since becoming a World Heritage Site, much work has been done to protect El Tajín. Research and reconstruction projects have made more of the site open to visitors. However, experts say more is needed to protect fragile murals. They also work to balance tourist needs with conservation. The number of visitors has grown to 653,000 annually.

Air pollution from oil drilling and power stations causes acid rain. This rain is eroding the detailed carvings on the soft limestone buildings. Experts say this is happening "at an alarming rate."

Important Ancient Buildings

The Entrance and Site Museum

The entrance to El Tajín is at the south end. Since 1992, new facilities have been added. These include a cafeteria, information services, and a museum. The traditional Danza de los Voladores (Dance of the Flyers) is performed here. The voladores appear every half-hour on a tall pole.

The Parque Takilhsukut is about one kilometer from the site. It's a modern center for Veracruz indigenous culture. It covers 17 hectares and can hold 40,000 people. It hosts fairs, events, and part of the annual Cumbre Tajín festival. There are also workshops, exhibitions, and ceremonies.

The site museum has two parts. One building holds smaller objects, mostly from the Pyramid of the Niches. A large stone altar from Building 4 is a highlight. It shows four people and intertwined snakes. These snakes represent the ball game marker.

The other part of the museum is a roofed area with large stone sculptures. Many fragments from the Building of the Columns are here. One tells the story of 13 Rabbit, a ruler of El Tajín. It shows him on a throne with a sacrifice victim. Warriors holding captives are also depicted.

The Arroyo Group: An Ancient Marketplace

This area is called the Arroyo Group because two streams surround it. It's one of the oldest parts of the city, covering over 86,100 square feet (8,000 square meters). Four tall buildings, named 16, 18, 19, and 20, surround it. These buildings once had temples on top.

The pyramids here are simpler than others at the site. Their niches are not as detailed. This plaza is unique because it has no smaller structures inside. Archeologists believe this was the city's marketplace. A deity related to trade was found here.

The market had stalls made of sticks and cloth. They offered local goods like vanilla. They also sold items from other parts of Mesoamerica. These included jaguar skins, exotic birds like parrots and macaws, and quetzal feathers. Slaves were also sold for service and sacrifice. West of the south building is a large ball court. It has carvings of the god Quetzalcoatl. When the city fell, many sculptures here were broken or reused.

The Pyramid of the Niches: A Masterpiece

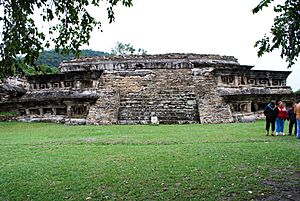

This pyramid has many names, like El Tajín and Temple of the Niches. It's the most famous building because of its unique design and good condition. It was also important in ancient times. Many sculptures were found here.

The pyramid is built from carefully cut stones. Some large stones weigh about eight tons. The stones fit together tightly with little mortar. The structure was originally covered in stucco and painted.

The pyramid has seven levels. Each level has a sloping base and a vertical wall, common in Mesoamerica. What's special are the decorative niches. The top is capped by a "flying cornice," a triangular overhang. The stones are arranged in neat lines. The pyramid was painted dark red, with black niches to make the shadows deeper.

Niches are also found under the stairway, showing it was added later. The original structure had 365 niches, matching the days in a solar year. At the top, there were tablets with serpent-dragons.

The niches represent caves, which were seen as paths to the underworld. Many gods were believed to live there. Caves with springs were sacred in Mexico. People would leave offerings like flowers and candles. Even in the mid-20th century, beeswax candles were found on the first level. While some think each niche held an idol, archeology has shown this isn't true. The most important part was the temple on top, but it was destroyed.

Sculptures from the temple are mostly broken. Larger tablets show the rain god, or a ruler dressed as the god. These scenes depict rituals or myths. This god seems to have been very important in El Tajín. The stairway has decorative frets called xicalcoliuhqui. These symbolize lightning and were likely painted blue. At the top of the stairway, there were probably two large stone statues. One is now in the museum.

The inside of the pyramid is filled with rocks and earth. Underneath it all is an older, smaller structure without niches. Two smaller buildings, Building 2 and Building 4, flank the pyramid. Building 4 contains an even older structure, possibly one of the first at the site.

Tajín Chico: The Elite Acropolis

Tajín Chico is a multi-level area that stretches up a hill. It was built using huge amounts of landfill. This is a large acropolis with many palaces and other government buildings. There are few temples here. It was also easier to defend than other parts of the city.

Tajín Chico means "Little Tajín" because people first thought it was a separate site. Now we know it was part of the city center. But the name stuck.

Building C was not a temple, but its purpose isn't fully clear. Nearby Buildings A and B were palaces. This building was likely used by priests or rulers to meet visitors. The roof of Building C was over 1,600 square feet (150 square meters). It covered two rooms and a main room with five pillars. The outside of the building is covered in stepped frets. These frets were painted dark red inside and light blue outside to look like niches. The wide eastern stairway had cloud-like scroll motifs.

Building B is a two-story palace used as a home. Like other buildings here, its roof is a thick cement slab. Another slab separates the ground and upper floors. The entrance from the plaza led to a single room. Six stone and cement pillars supported the floor above. These columns were made thicker over time for more support. A narrow stairway leads to the more spacious upper floor. This is the only multi-story palace found outside the Mayan areas.

Building A has two levels, stepped frets, and niches. It looks similar to buildings in the Yucatán. The lower level is a solid base, not rooms. It's decorated with large red panels. The entrance on the south side is very detailed. The upper level has a corridor and several rooms. This level was decorated with yellow, blue, red, and black stepped frets and scrolls. Murals once covered the panels inside, but only fragments remain.

Building A was built over older buried buildings. Some parts, like the buttresses, have been damaged by settling. The front of the building has false stairs and balustrades with stepped frets and niches. It's unknown if its similarity to the Pyramid of the Niches means they are related. The false stairs were once painted with blue and yellow scroll motifs. True stairs lead up under an arch to the first level of the palace.

The Building of the Columns is at the highest point of Tajín Chico. It's part of one of the last building groups built at El Tajín. These buildings sit on a platform-terrace. Another structure here is the Annex, connected by a passageway. Behind these buildings is a large plaza.

This building is named for the columns on its east side. The columns were made by stacking cut flagstone circles. Their surfaces were carved with scenes celebrating a ruler named 13 Rabbit. Most column remains are in the site museum. This building also had a cement roof, arched in the "porch" area. It had an inner courtyard and was decorated with painted stepped frets and symbols. This complex was among the last built and shows fire damage from the city's fall.

East of Tajín Chico is a valley floor area with many buildings. Most are not open to visitors yet. Two have been partly explored. The first is the Great Xicalcoluihqui, or Great Enclosure. This is a wall that forms a giant stepped fret from above. It encloses about 129,000 square feet (12,000 square meters). This structure is unique in Mesoamerica and has two or three small ballcourts. The wall has sloping sides and free-standing niches, like the Pyramid of the Niches. It has over a hundred niches and several entrances.

The other structure is the Great Ballcourt, the largest at El Tajín. It's at the northwest corner of the Great Xicalcoluihqui. It has vertical sides and is about 213 feet (65 meters) long. Unlike other ballcourts, it has no carved panels or sculptures.

Buildings 3, 23, 15, and 5

Building 3, or the Blue Temple, is different from other pyramids. Except for six benches, it has no niches. Its seven levels have gently sloping walls. The unreconstructed north side has a large dent from looters. No sculptures or temple remains have been found here. The building was covered in cement several times. Each layer was painted blue, not the usual red. Blue is often linked to the rain god, but there's no other proof here.

Building 23, next to the Blue Temple, was built very late in Tajín's history. It has five levels of almost vertical walls without niches. The original staircase was destroyed and rebuilt. The stairs are made of lime, sand, and clay without a stone core. The inside is loose stone. At the top, where the temple was, are stepped merlons that look like castle battlements.

South of Buildings 3 and 23 is Building 15, which is only partly dug up. It faces west and seems to have been a government building, like Building C. It has stairways on both east and west sides to the second level. The third level begins with a wall of niches and no visible stairs. The two lower levels have larger niches. Beneath these are seven panels. An older, damaged structure was found underneath this building. This building is thought to be the last one built with niches.

Building 5 is considered one of the most impressive at El Tajín. It's next to the Pyramid of the Niches but still stands out. It's in the center of a pyramid complex. It has a pyramid rising from a platform over 32,000 square feet (3,000 square meters) in size. The first level, lined with niches, is reached by a single staircase on the west or a double staircase on the east. A double staircase on the east leads to the top, where the temple once stood.

The top of the pyramid has two platforms decorated with stepped frets. Between the two east staircases is a tall, column-like sculpture. It was broken in ancient times but reassembled by archeologists. The sculpture looks like the carved stone yokes of Veracruz. It shows a seated figure with a skull for a head. Its arms hold a serpent-like form, and scrolls on the body may mean sacrificial blood. The small buildings around this pyramid were meant to complement it.

The North and South Ballcourts: Ritual Games

The North Ballcourt is made of three layers of large flagstones. It has six carved panels with ritual scenes and a decorative frieze along both walls. The court is 87 feet (26.5 meters) long, which is quite small. It has vertical walls instead of sloping ones. It's likely one of the oldest structures at Tajín.

Some parts of the panels and friezes are worn away. The four end panels show scenes from the ball game ritual, asking for help from the gods. The central panels show the gods responding or doing their own rituals. Different forms of the pulque god appear over the end panels. This suggests pulque was important in the ritual.

The southeast, east, and northwest panels show a ruler on a throne. The southwest panel has a figure dressed as an eagle in a vat of liquid, probably pulque. Two figures are feeding it. The north central panel shows two figures facing each other. One is on a throne, the other by a pulque vat. In the middle are two intertwined serpents forming a ball game marker. The friezes along the top edges have interlocking scroll figures. Many have feathered headdresses and reptile features.

The South Ballcourt also has vertical, sculpted walls. Its carved panels are mostly intact. They show step-by-step how the ball game was played, including ceremonies, sacrifice, and the gods' reactions. The court is about 198 feet (60 meters) long and 34.5 feet (10.5 meters) wide. Spectators could watch from Buildings 5 and 6, and from stands.

The court is made of huge stones, some weighing ten tons. After the walls were built, six panels were carved at the corners and centers. The end panels show scenes from the game. The center panels show the gods' responses.

The southeast panel shows the opening ritual. A main player is dressed up and given spears. This happens before the game starts. The death deity watches, rising from a vat of liquid, possibly pulque. Symbols above the deity link it to the planet Venus.

The southwest panel shows another ceremony. The main player lies on a sofa. Two musicians play a turtle shell drum and clay rattles. An eagle-dressed figure dances, while a skeletal deity flies above. The death deity rises from liquid again.

The northwest panel shows the start of the game. Two players stand in the center, speaking. One holds a large knife. Between them are intertwined slashes, the ball game symbol, and a ball. They wear protective gear similar to stone yokes. Two figures, one with a deer head, watch from the walls. The death deity is also above.

The northeast panel shows the game has ended. One player is about to be sacrificed by having his head cut off. Three figures wear ball game clothes. The center figure's arms are held back. The figure on the right holds a large knife at the center figure's neck. Scrolls show speech from the sacrifice, and the skeletal god is depicted.

After this, the panels show the gods' reactions. The north central panel shows the ritual continuing in the afterlife. It connects El Tajín society to the gods. In the center is a temple with rain and wind gods on top. A vat of liquid is inside. The sacrificed player appears whole, with a pot. He points to the vat and speaks to the rain god. A reclining chacmool protects the liquid and speaks. The player is asking for pulque. A glyph shows the mythical origin of the drink.

The south central panel shows a scene after the player receives pulque. It has the same temple, glyphs, and pulque god. Differences include the moon as a rabbit, the rain god in front of the temple, and a lower liquid level in the vat. The rain god performs a self-sacrifice ritual, letting blood fall into the vat to refill it with pulque.

The Cumbre Tajín Festival

The Cumbre Tajín is an annual arts and culture festival held at El Tajín in March. It's a celebration of Totonac identity. The Totonacs are seen as the guardians of El Tajín. The festival includes traditional Totonac culture and modern arts from around the world.

Events include music concerts, experiencing a temazcal (traditional sweat lodge), and theater. Visitors can also see El Tajín at night. There are over 5,000 activities in total. Many cultural, craft, and food events happen at the nearby Parque Takilhsukut. In 2008, 160,000 people attended. Thirty percent of the money earned goes to scholarships for Totonac youth.

In 2009, the festival added the International Encounter of Voladores. For five days, voladores from different places perform. The goal is to see different styles and share experiences about this fertility ritual. Voladores come from places like San Luis Potosi and Guatemala.

Some people have criticized Cumbre Tajín. They say it focuses too much on modern shows instead of cultural events. For example, lighting up the pyramids at night without historical information. Critics worry this disrespects the site and the Totonac people. There are also fears that large crowds from concerts could damage the site. However, the Indigenous Arts Center of Veracruz works hard to preserve Totonac culture through the event. They sponsor traditional cooking, painting, and the Voladores ritual.

See also

In Spanish: El Tajín para niños

In Spanish: El Tajín para niños