Pulque facts for kids

Bottle of unflavored pulque with bamboo cap

|

|

| Type | fermented alcoholic drink |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Mexico, (Mesoamerica) |

| Introduced | Ancient, before AD 200 |

| Alcohol by volume | 5–7% |

| Proof (US) | 10–14° |

| Color | milky-white |

| Ingredients | sap of Agave americana |

| Related products | mezcal, bacanora, raicilla, tequila |

Pulque (which is also called octli) is a special drink made from the sap of the maguey plant. This sap is allowed to ferment, which means it changes naturally over time. Pulque is a very old drink from central Mexico, where people have been making it for thousands of years. It looks like milk, is a bit thick, and tastes a little sour, like yeast.

Long ago, in the Mesoamerican period, pulque was considered a sacred drink. Only certain people were allowed to drink it. After the Spanish came to Mexico, the rules changed, and more people started drinking it. Pulque was most popular in the late 1800s. However, in the 1900s, its popularity went down, mainly because beer became more common. Today, some people are trying to make pulque popular again, especially through tourism.

Contents

What is Pulque?

Pulque is a milky-white liquid that is a bit thick and can have a light foam on top. It is made by fermenting the sap from certain types of maguey (agave) plants. This is different from mezcal, which is made from the cooked heart of agave plants. Tequila is a type of mezcal, mostly made from the blue agave plant. About six different kinds of maguey plants are best for making pulque.

The word pulque comes from the Nahuatl language. The original name for the drink was iztāc octli, meaning "white pulque." The Spanish might have accidentally called it "pulque" from the Nahuatl phrase octli poliuhqui, which meant "spoiled pulque."

The Maguey Plant

The maguey plant is also known as the "century plant" in English. It grows naturally in Mexico, especially in the cool, dry highlands of states like Hidalgo and Tlaxcala. People have been growing maguey since at least 200 CE in places like Tula and Teotihuacan. Wild maguey plants were used even earlier.

This plant has many uses. Its thick leaves provide fibers for making rope or fabric. Its thorns can be used as needles. The thin layer covering the leaves can even be used as paper or for cooking. The Spanish gave the plant the name maguey, which they learned from the Taíno people. In Spanish, it is still commonly called maguey, while its scientific name is Agave. In Nahuatl, the plant is called metl.

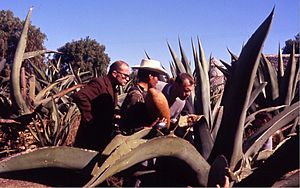

Making pulque requires the maguey plant to "die" in a way. As the plant gets older, its center swells up. It prepares to grow a tall flower stalk, which can be up to 20 feet high. But for pulque, this flower stalk is cut off. This leaves a hollow space in the center, about 12 to 18 inches wide. In this space, the maguey sap, called aguamiel (honey water), collects. A maguey plant needs about 12 years to grow enough to produce this sap for pulque.

Pulque's Ancient History

Myths and Legends

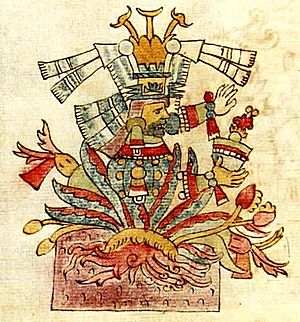

People have been drinking pulque for at least 2,000 years. Its beginnings are told in many stories and myths. Most of these stories involve Mayahuel, who is the goddess of the maguey plant. People believed that the aguamiel collecting in the plant was her blood. Other gods, like the Centzon Totochtin (400 rabbits), are also linked to pulque. They represent the different effects of the drink and are said to be Mayahuel's children. One story says Mayahuel was a human woman who found out how to collect aguamiel. Then, someone named Pantecatl discovered how to make pulque from it.

Another tale says the Tlacuache (opossum) found pulque. He used his hands to dig into the maguey and drink the naturally fermenting juice. He became the first one to get drunk. People thought Tlacuache decided where rivers would flow. The rivers he made were usually straight, except when he was drunk, then they would wander like his path from one place to another.

A different story says aguamiel was found during the Toltec Empire. A noble named Papantzin wanted the emperor to marry his daughter, Xochitl. He sent her to the capital with aguamiel as a gift. The emperor and princess got married, and their son was named Meconetzin, meaning "maguey son." In some versions of this story, Xochitl herself is given credit for discovering pulque.

Before the Spanish Arrived

The maguey plant was one of the most important and sacred plants in ancient Mexico. It played a big role in their myths, religious ceremonies, and economy. Pulque appears in many old drawings and carvings from before the Spanish arrived, starting around 200 CE. A famous painting called "The Pulque Drinkers" was found in 1968 at the pyramid of Cholula. It shows people drinking pulque. People probably discovered aguamiel and fermented pulque by watching animals like rodents. These animals would gnaw on the plant to drink the sap that seeped out. Sometimes, the sap would even ferment inside the plant itself.

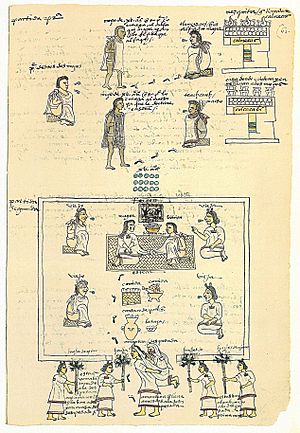

For the native people of central Mexico, drinking pulque was only allowed for certain people and at certain times. It was a ritual drink, used during festivals for goddesses like Mayahuel and gods like Mixcoatl. Priests and people who were going to be sacrificed drank it. This was to make the priests more excited and to help the victims feel less pain. Many old Aztec books, like the Borbonicus Codex, show that nobles and priests drank pulque to celebrate victories. Regular people were only allowed to drink it if they were elderly or pregnant women. Making pulque was also a ritual, and the brewers were very superstitious.

During Colonial Times

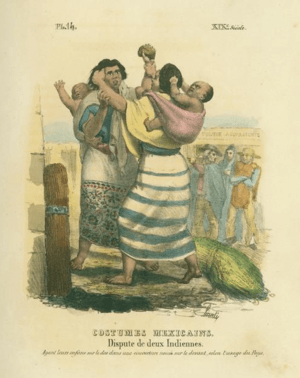

After the Spanish arrived, pulque lost its sacred meaning. Both native people and Spanish people started drinking it. At first, the Spanish did not make any laws about it. Pulque became a good source of tax money. But by 1672, too much public drinking became a problem. So, the government made rules to control how much pulque was consumed. Only 36 "pulquerias" (places that sold pulque) were allowed in Mexico City. These places had to be open, have no doors, and close at sunset. Food, music, dancing, and men and women mixing were not allowed.

Even with these rules, pulque was still very important to Mexico's economy during colonial times and after Mexico became independent. It was the fourth biggest source of tax money. In the late 1600s, the Jesuits started making pulque on a large scale to pay for their schools. This changed pulque from a homemade drink to one made in big businesses.

After Independence

Pulque production grew a lot after Mexico became independent. Rules on pulque makers ended, and Mexican pride increased. From then until the 1860s, pulque haciendas (large farms) grew in number, especially in Hidalgo and Tlaxcala. In 1866, the first railway between Veracruz and Mexico City opened. This train line went through Hidalgo and soon became known as the "Pulque Train." It brought fresh pulque to the capital every day. This easy production and shipping made Hidalgo rich. It also created a "pulque aristocracy," which included some of the most powerful families of that time. At its peak, there were about 300 pulque haciendas. Some still exist today in the plains of Apan and Zempoala, Hidalgo. Pulque was most popular in the late 1800s, enjoyed by both rich and poor people.

Photographers like C. B. Waite, Hugo Brehme, and Sergei Eisenstein took pictures of tlaquicheros (pulque collectors), pulquerías, and pulque haciendas. The tlaquichero was a very well-known image of Mexican people. Even in 1953, Hidalgo and Tlaxcala still got 30% and 50% of their money from pulque. This has changed as new roads and farming methods have made other businesses more profitable.

Why Pulque Declined

Today, pulque makes up only 10% of the alcoholic drinks consumed in Mexico. It is mostly drunk in the central highlands, especially in rural and poorer areas. It is often seen as a drink for the lower class, while European-style beer became very popular throughout the 1900s.

Pulque's complex and delicate fermentation process always made it hard to distribute widely. It does not stay fresh for long, and moving it around too much makes it spoil faster. So, since ancient times, it has mostly been drunk in central Mexico.

Pulque's decline started in the early 1900s during the Mexican Revolution, which slowed down its production. In the 1930s, the government tried to reduce alcohol consumption, which also affected pulque. But the biggest reason for pulque's decline was the rise of beer.

European beer makers in the early 1900s ran campaigns against pulque. They claimed that pulque producers used a muñeca (doll), which was a cloth bag containing animal waste, to speed up fermentation. Some pulque makers say this was a complete myth. However, historians suggest it might have happened sometimes, but rarely. Beer producers spread the idea that pulque was generally made this way, often through rumors. This was done to hurt pulque sales and promote beer, which they said was "clean and modern."

This plan worked. Pulque is now often looked down upon and drunk by fewer people. Mexican-made beer is everywhere and very popular. Pulque's popularity is low and keeps falling. Twenty years ago, about 20 trucks would bring pulque to Xochimilco (in Mexico City) every three days. Now, only one or two trucks come. Only five pulquerías remain in that area, where there used to be 18. The situation is similar in most other parts of Mexico. The remaining pulquerías are small, selling pulque made by small producers.

In Hidalgo, where most maguey is grown, maguey fields are disappearing. Barley is being planted instead. Many maguey plants now just mark property lines. Many of these plants do not last long because they are often damaged. About 10,000 plants are cut or destroyed each week. People cut off lower leaves for barbacoa (a type of cooked meat) or destroy the plants to find edible grubs or ant eggs inside them.

Recently, some travel shows have shown pulque as a popular drink again. There is a new trend among young people who want to connect with their Mexican heritage by drinking it. It has become a trendy drink for young people and those interested in their roots. Also, the old rule about women not drinking pulque has been lifted. Now, pulquerías are open to both men and women. Many pulquerías now offer flavored pulque, with some places having as many as 48 different flavors.

How Pulque is Made

The process of making pulque is long and needs careful attention. The maguey plant must grow for 12 years before its sap, or aguamiel, can be collected. But a good plant can produce sap for up to a year. This aguamiel can be drunk as is, but it only becomes alcoholic after it ferments. This liquid is collected twice a day from the plant, yielding about five or six liters daily. Today, people use a steel scoop to collect the liquid. In the past, they used a long gourd like a straw to suck out the juice. Between collections, the plant's leaves are bent over the center to keep out bugs and dirt. The center is regularly scraped to keep the plant producing sap. Most maguey plants produce aguamiel for about four to six months before they die. Some plants can give up to 600 liters of pulque.

The collected juice is put into 50-liter barrels and taken from the field to large fermentation vats. These vats, called tinas, are in a special building called a tinacal. This name comes from the Spanish word tina (vat) and the Nahuatl word calli (house). When pulque haciendas were most popular in the late 1800s, life on the hacienda revolved around these tinacals. A tinacal was usually a stone building with a wooden roof. The upper parts of the walls were open for air, and the outside walls were sometimes decorated with native designs or pictures related to pulque making. A popular design was the story of Xochitl discovering pulque. Other common pictures were the hacienda's patron saint and the Virgin of Guadalupe. Inside, the vats were made of cowhide stretched over wooden frames, lined up against the walls. In bigger tinacals, there were three or four rows of vats. Today, the tinas are made of oak, plastic, or fiberglass and can hold about 1,000 liters each.

After the juice is in the vats, a small amount of already fermented pulque (called semilla or xanaxtli) is added to start the process. Unlike beer, which uses yeast, pulque ferments because of a type of bacteria called Zymomonas mobilis. Those who manage the fermentation process keep their methods secret, passing them down from father to son. Fermentation takes about seven to 14 days. It seems to be more of an art than a science. Many things can affect the fermenting pulque, like temperature, humidity, and the quality of the aguamiel.

The process is tricky and can go wrong easily. Because of this, and perhaps its old "sacred" meaning, there are rituals and rules. People might sing religious songs or say prayers. Women, children, and strangers are not allowed inside the tinacal. Other beliefs include not eating canned fish or wearing a hat inside the tinacal. Eating canned fish is said to make the pulque taste bad, and wearing a hat is considered bad luck. To fix bad luck, the person who made the mistake must fill their hat with pulque and drink it all.

Just before the pulque is fully fermented, it is quickly shipped to market in barrels. The fermentation process continues, so pulque must be drunk within a certain time before it spoils.

Drinking Pulque

Most pulque is drunk in bars called pulquerías. In the early 1900s, there were over 1,000 of them in Mexico City alone. By then, pulquerías became accepted places, and some were very fancy. But whether for rich or poor, two things stood out: unusual or catchy names, and murals on the walls. Names included "My Office," "Memories of the Future," and "I'm Waiting for You Here at the Corner." Diego Rivera, a famous painter, once said that the murals in pulquerías were an important part of Mexican painting. A tradition in pulquerías in the early 1900s was to put sawdust on the floor. People would start drinking by spilling a little pulque on the floor as an offering to Mother Earth.

Traditional pulquerías often feel like private clubs. New visitors might be ignored or stared at. Visiting often and drinking a lot usually helps you get accepted. While some places might not allow women, it is more common for them to have a separate seating area for women. Men and women are not allowed to mix. In the rural areas of Hidalgo and Tlaxcala, where most pulque is made, the pulque is fresher and tastes better. A vendor usually hangs a white flag over the door when a new shipment has arrived.

Traditionally, pulque is served from large barrels kept on ice. It is poured into glasses using a jicara, which is half of a calabash tree gourd. The person serving the drinks is called a jicarero. In a pulquería, cruzado, meaning "bottoms up," is a common toast.

The drinking glasses have fun names that can show how much pulque a customer can drink. Large two-liter glasses are called macetas (flower pots). One-liter glasses are cañones (cannons). Half-liter glasses are chivitos (little goats). Quarter-liter glasses are catrinas (dandies), and eighth-liter glasses are tornillos (screws). These glasses are traditionally made from greenish, hand-blown glass. Pulque can be drunk plain or with added fruits or nuts. Pulque prepared this way is called curado or "cured."

One reason pulque has not been more popular is that it cannot be stored for long or shipped far. Recently, pulque makers have found a way to preserve it in cans. However, they admit this changes the flavor a bit. The hope is that this new method will help pulque regain its popularity in Mexico and even be exported, like tequila. It is already sold in the United States by a company called Boulder Imports, under the brand "Nectar del Razo." The first customers were Mexican-American men. But the company says the product is also popular as a health food, sought by athletes and bodybuilders.

Nutritional Benefits of Pulque

There is a saying about pulque: "sólo le falta un grado para ser carne" – meaning "it is only a bit shy of being meat." This refers to how nutritious the drink is thought to be. In ancient times, pregnant women and elderly people were allowed to drink it, even though it was usually only for priests and nobles. Modern studies of pulque have found that it contains carbohydrates, vitamins C, B-complex, D, and E. It also has amino acids and minerals like iron and phosphorus.

Pulque Tourism

From the time when pulque was very popular, the state of Hidalgo had about 250 pulque haciendas. Many of these have been left empty or changed for other uses, like ranching. Their tinacals have either disappeared or been turned into storage rooms or party spaces. A few still make pulque, but they use more modern and clean facilities.

In Tlaxcala, the federal Secretariat of Tourism and the state government have created a tour called the "Pulque Route." This tour visits the main haciendas that still make pulque in the state. It is a two-day trip that starts at the Church of La Barca de la Fe in Calpulalpan. It then goes to the San Bartolo Hacienda, which is the main exporter of canned pulque. This hacienda used to belong to Ignacio Torres Adalid, who was known as the "king of pulque." Today, it belongs to Ricardo del Razo. The tour also includes visits to maguey fields, like those around a town called Guillermo Ramirez.

These old haciendas were very different from each other. Some were very grand and beautiful, like the Montecillos Hacienda. It was built in the 1600s by the Jesuits in a Spanish colonial style. The San Antonio Ometusco Hacienda was built by architect Antonio Rivas Mercado. However, most haciendas were built over time, starting in the 1500s, with a mix of Mexican and European building styles. A special feature of many was their Neo-Gothic towers. The Santiago Tetlapayac Hacienda has murals about charreada (Mexican rodeo) that are thought to be by the painter Icaza. The Zotoluca Hacienda has an eight-sided shape in a Neo-Moorish style and was restored in the 1950s.

But the most important part of each pulque hacienda was the tinacal. They were designed and decorated to show their importance. Almost all have interesting architectural details, like a specially decorated main doorway, murals, or carved windows. Some are considered works of art, such as the tinacal at the Montecillos Hacienda. The one at the San Antonio Ometusco Hacienda also has an elegant roof over the shipping area with iron columns and walls decorated with murals about pulque's history.

|

See also

In Spanish: Pulque para niños

In Spanish: Pulque para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |