Chacmool facts for kids

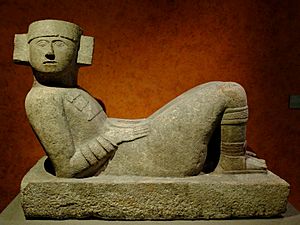

A chacmool (sometimes spelled chac-mool) is a special type of stone statue from ancient Mesoamerica. These statues show a person lying down, looking sideways, and resting on their elbows. They hold a bowl or a flat disk on their stomach. People think these figures might have been brave warriors. They carried offerings to the gods. The bowl on their chest was used for special offerings. These could include drinks like pulque, foods like tamales and tortillas, tobacco, turkeys, feathers, and incense. For the Aztecs, the bowl was called a cuauhxicalli. It was a stone bowl used for important rituals. Chacmools were often found near special stones or thrones.

Aztec chacmools often showed water. They were linked to Tlaloc, the god of rain. These statues were seen as a connection between the human world and the world of the gods. They first appeared around the 800s AD. This was in the Valley of Mexico and the northern Yucatán Peninsula.

Contents

What a Chacmool Looks Like

The chacmool is a unique type of ancient Mesoamerican statue. It shows a figure lying down, with its head turned to the side. The figure rests on its elbows. It holds a bowl or a disk on its chest. Chacmools can look very different from each other. Some have heads facing right, others left. Some even look straight up. A few have heads that can move.

The figure might be lying on its back or side. Its stomach can be lower than its chest and knees, or at the same level. Some chacmools were placed on rectangular bases. Some figures wear fancy clothes. Others are almost naked.

Chacmools from Chichen Itza and Tula show young men who look like warriors. But chacmools from Michoacán show older men with wrinkled faces. One chacmool from Guácimo, Costa Rica, looks like a mix of a human and a jaguar. It holds a bowl that was likely used to grind food.

Artists used many materials to make chacmools. These included limestone, hard metamorphic rocks, and igneous rocks. They also used ceramic and cement.

How Chacmools Were Found and Named

We don't know the original name for these statues. The word chacmool comes from “Chaacmol.” This name was given by Augustus Le Plongeon in 1875. He and his wife, Alice Dixon Le Plongeon, found a statue at Chichén Itzá. Le Plongeon thought “Chaacmol” meant “paw swift like thunder” in Yucatecan Mayan. He believed the statue was of an old ruler of Chichen Itza.

Le Plongeon's friend, Stephen Salisbury, published the discovery. He changed the spelling to "Chac-Mool." Le Plongeon wanted to show the statue in Philadelphia in 1876. But Mexico's president said no. In 1877, the statue was taken to Mérida. Later, it went to Mexico City. It is now at the National Museum of Anthropology. A museum worker named Jesús Sanchez noticed that this statue looked like two others from central Mexico. This showed that chacmools were found in many places.

Finding chacmools in both central Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula was important. It helped people think there was a large Toltec empire. But the chacmool statues might have first appeared in the Maya region. Even though the name chacmool wasn't the original, it helps us talk about these similar statues. In Michoacán, they are called Uaxanoti, which means "The Seated One" in the Purépecha language.

Where Chacmools Are Found

Chacmool statues have been found all over Mesoamerica. This includes Michoacán in Mexico and as far south as El Salvador. The oldest ones are from around 800–900 AD. You can find them in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan. They are also in the central Mexican city of Tula. And in the Maya city of Chichen Itza in the Yucatán Peninsula.

Fourteen chacmools are known from Chichen Itza. Twelve are from Tula. The chacmool from the palace at Tula is from around 900–1200 AD. Other chacmools have been found in Acolman, Cempoala, Michoacán, Querétaro, and Tlaxcala.

At Chichen Itza, five chacmools were found in their original places. These were in the Castillo, the Chacmool Temple, the North Colonnade, the Temple of the Little Tables, and the Temple of the Warriors. The others were found buried nearby. The five found in their original spots were all near entrances. They were close to a special seat or throne. Chacmools in Tula were also linked to thrones. They were either in front of a throne or at the entrance to a room with one.

Two chacmools were found near the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan. This was the Aztec capital. The first was found in 1943. The second was found in the sacred area. This one is special because it is the only fully colorful chacmool ever found. It had an open mouth and teeth. It stood in front of the temple of Tlaloc, the Aztec rain god. Its sculpted bowl likely received special offerings. This colorful statue is much older than the first one found.

Chacmools have been reported as far south as the Maya city of Quiriguá. This is near the border of Guatemala and Honduras. The Quiriguá chacmool is likely from a later time. It looks more like those from Tula than Chichen Itza. Two chacmools were found at Tazumal, a Maya site in western El Salvador. One was also found at Las Mercedes in Guácimo, Costa Rica.

When and Where Chacmools Started

The oldest chacmool found is from around 800–900 AD. This type of statue was not known in big ancient cities like Teotihuacán and Tikal. After they first appeared, they quickly spread across Mesoamerica. They reached as far south as Costa Rica. Most people think they started in central Mexico. But there are no older examples before the Toltecs. And they don't appear in central Mexican ancient books.

The way chacmools are placed and what they are near is similar to older Maya art. Some art experts believe chacmools grew out of Maya art from earlier times. No central Mexican chacmool has been found that is clearly older than those from Chichen Itza. However, Tula and Chichen Itza might have developed them at the same time. They could have quickly shared the idea of the chacmool.

Chichen Itza has a wider variety of chacmool shapes. This also suggests they might have developed there first. No two chacmools from Chichen Itza look exactly alike. At Tula, the chacmools look very similar to each other. One expert thinks the chacmool developed from Maya pictures. Then, it became a 3D statue at Chichen Itza. This might have been helped by ideas from central Mexican statues. A chacmool from Costa Rica was dated to about 1000 AD.

Aztec Chacmools and Their Colors

During an excavation in the 1930s, a very colorful chacmool was found. It was at the Templo Mayor, on the side dedicated to Tlāloc, the rain god. This statue was in the same spot as a special stone on the other side of the temple. This suggests the chacmool acted as a messenger. It was a link between the temple priests and the god Tlaloc.

The colors on this chacmool were very important. They helped experts figure out what the figure meant. Even though it was linked to Tlaloc, it didn't have many of his usual symbols. Experts carefully cleaned the statue. They used special tools to see the colors better. They found similarities to other Aztec chacmools. These included a round gold chest piece, colors on the skirt, black skin, red hands and feet, and a white headdress. All these details showed it was connected to Tlaloc.

A second chacmool was found at the Templo Mayor later. It had different features. But these features matched other statues found there. These included Tlaloc ritual vessels and bench carvings. One unique feature was the eyes. Tlaloc's eyes are usually round, like goggles. But this later chacmool had rectangular eyes with almond shapes inside. All three statues also had large fangs at the corners of the god's mouth.

The jewelry on this later chacmool was also different. Instead of typical square earplugs, it had very large round ones. All three examples also wore a beaded necklace. One strand had bigger beads that looked like hanging bells. This chacmool held a cuauhxicalli vessel. This vessel also had the god's face carved on it, with the same rectangular eyes and mouth.

Chacmools in Modern Times

The Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes wrote a short story called "Chac Mool." It was in his book Los días enmascarados (The Masked Days), published in 1954. In the story, a man buys a chacmool statue. He finds that the stone slowly turns into flesh. The idol becomes fully human. It takes over his life and causes floods. The man dies by drowning. His story is found in a diary. It describes the scary things the idol did. It also tells of his plans to escape. The author said he got the idea from news reports in 1952. A Maya rain god statue was loaned to an exhibit in Europe. It rained a lot there at the same time.

The artist Henry Moore was inspired by chacmool statues. He saw one in Paris. He said that its "stillness and alertness" and "the whole presence of it" inspired his own sculptures. He especially liked how the legs came down like columns.

See also

In Spanish: Chac mool para niños