The Codex Ixtlilxochitl facts for kids

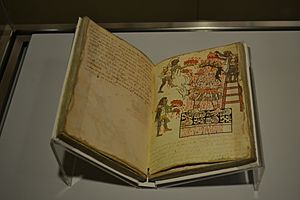

The Codex Ixtlilxochitl is an ancient Aztec book filled with pictures. It was made between 1580 and 1584, after the Spanish arrived in Mexico. This special book records old ceremonies and holidays that took place at the Great Teocalli (a ceremonial temple) in the Aztec city of Texcoco. Texcoco was near what is now Mexico City.

The codex also shows pictures of important rulers and gods connected to Texcoco. It's a great example of how Aztec and Spanish cultures mixed during the 1600s. People from both cultures tried to find a balance between old traditions and new ideas. Unlike earlier Spanish efforts to destroy native culture, this codex helped Europeans understand Aztec ways. It shows how Europeans became interested in these cultures, which helped save valuable information about them.

Contents

How the Codex Looks

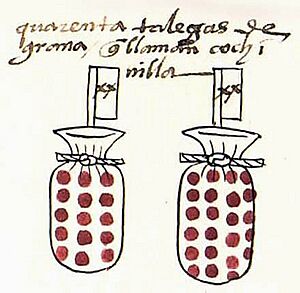

The Codex Ixtlilxochitl was made using traditional Aztec methods and some new Spanish techniques. Pages 94 to 104 use colors from nature, just like older Aztec books. For example, red came from cochineal insects. Yellow came from tecoçahuitl stones and flowers. Black was made from tree sap and charcoal. Green came from trees, and blue from herbs. Other soft colors came from crushed minerals.

On pages 105 to 112, you can see Spanish influence. The pictures of rulers and gods look more realistic. The colors are brighter, and some details have real gold leaf. Also, these pages are made from European paper, not the traditional bark of wild fig trees. The last pages, 113 to 122, have no pictures. They are only written with European ink.

In total, the codex has 27 pages of European paper and 29 illustrations. The book itself is about 21 by 31 centimeters (about 8 by 12 inches) in size.

The Codex's Story

We don't know who drew the pictures in the codex. But we think they were Aztec artists working for Spanish priests. The priests wanted to identify Aztec rituals they considered against their Catholic beliefs. The Codex Ixtlilxochitl is actually three different documents put together.

A nobleman and historian named Fernando de Alva Cortez Ixtlilxochitl (who lived from about 1578 to 1650) assembled the codex. He was important because he was a direct descendant of Aztec rulers Ixtlilxochitl I and Ixtlilxochitl II. These men were tlatoani (rulers) of the altepetl (city-state) of Texcoco.

Fernando de Alva Cortez Ixtlilxochitl was a government archivist. He was very skilled at understanding and writing down Aztec culture and language. The viceroy of New Spain, Luis de Velasco, asked him to translate between Spanish and Nahuatl speakers. He also asked him to write down the history of the Aztec people. The Codex Ixtlilxochitl was part of this work. It mainly talks about Aztec gods, rulers, religious rituals, and their calendar dates.

The Codex Ixtlilxochitl belongs to a group of three codices called the Magliabechiano Group. These books are all about Aztec religion and rituals. The other two are the Codex Magliabechiano and the Codex Tudela.

Many other well-known Aztec codices made after the Spanish conquest focus on life in Tenochtitlan. This was the biggest city in the Aztec empire and is now Mexico City. But the Codex Ixtlilxochitl mostly shows life in Texcoco. This gives us a wider view of daily life in other Aztec regions.

The Spanish often commissioned these codices to help convert native people to Catholicism and end the Aztec religion. However, the Codex Ixtlilxochitl shows the complex relationship between the Spanish and the Aztecs. This relationship led to enough native practices being saved for historians to learn a lot about Aztec culture.

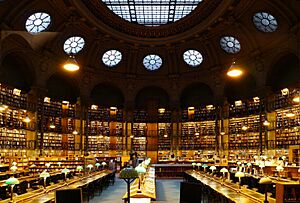

After the codex arrived in Europe, it was used for Spanish surveys. It then passed through many hands of Mexican and European historians and collectors. Eventually, it was owned by a Mexican-French collector named E. Eugene Goupil. After Goupil died in 1895, his family donated the codex to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. It is still there today. The pages of the codex have stamps from the Bibliothèque Nationale and Goupil's personal library. They also have page numbers added by earlier owners.

Parts of the Codex

Section 1: Calendar and Holidays

The first part of the codex, pages 94 to 104, is a copy of an older document. This older document recorded important gods and holidays at Texcoco's Great Teocalli (ceremonial temple). The original document, called the Magliabechiano Prototype, was made between 1529 and 1553 but was later lost. This section of the Codex Ixtlilxochitl helps preserve parts of it. Because it contains parts of this lost prototype, the codex is linked to the Magliabechiano Group.

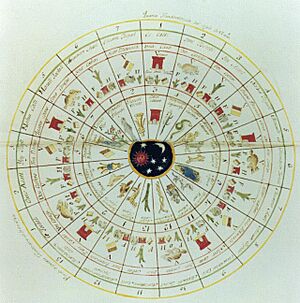

This section shows the Xiuhpohualli solar calendar. This calendar has 365 days, divided into 18 months of 20 days each. These months were called veintenas in Spanish or mētztli in Nahuatl. Each month had its own special feast. At the end of the 18 months, there was a 5-day period called the nemontemi. These were considered "unlucky" days when people avoided many daily activities to prevent bad luck.

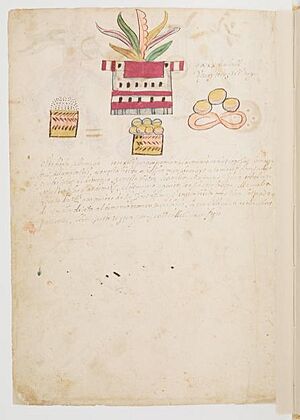

Each page in this section shows a month with a picture. These pictures range from human figures for the month Atlcahualo to clothing for Tozoztontli, and also animals, buildings, and food. Below each picture, Spanish historians wrote comments around the year 1600. This section also describes two funeral rituals.

Section 2: Rulers and Gods

This section, pages 105 to 112, has illustrations for a 1577 report by Juan Bautista Pomar. This report was a census (a count of people and information) for the Spanish king, Philip II of Spain. The king sent questionnaires to his colonies to learn more about native culture, religion, and daily life. This helped the Spanish set up better government systems. The information for the Codex Ixtlilxochitl was completed in 1582. It includes six detailed illustrations with Spanish notes.

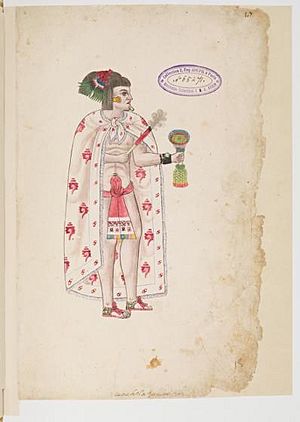

In this section, you can clearly see how European art influenced the Aztec pictures of gods and rulers. The figures have correct body shapes and realistic expressions. The artists used shading to make them look lifelike. The first illustration shows the Aztec emperor, or tlatoani, Ixtlilxochitl Ome Tochtli. He is better known as Ixtlilxochitl I. He ruled Texcoco from 1409 to 1418, before the Spanish arrived in 1519. The picture shows him standing tall in royal clothes. He wears a fancy woven cloak and holds an arrow in his left hand and a ceremonial scepter in his right. Ixtlilxochitl I is known for losing Texcoco in a battle to Tenochtitlan. His son, the famous "poet-king" Nezahualcoyotl, later won it back.

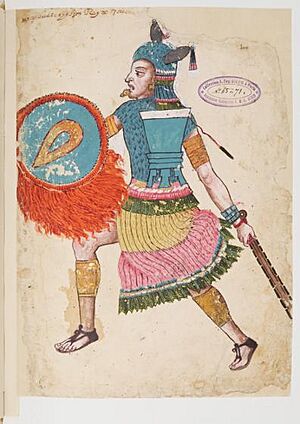

Nezahualcoyotl himself is shown next in this section. He is dressed for battle, which fits Texcoco's history. The artist shows him with a fierce look. Gold leaf was carefully added to his leg and arm bands to make him look very regal. He holds an obsidian-edged sword, called a macuahuitl, and carries a feathered shield and armor. You can imagine Nezahualcoyotl going into battle to avenge his father, win back his throne, and rebuild Texcoco.

The third image is another picture of Ixtlilxochitl I. This illustration is simpler in size, color, and detail. But the king's cloak with a snail shell pattern and his ceremonial incense burner still show the richness of Aztec royal clothing.

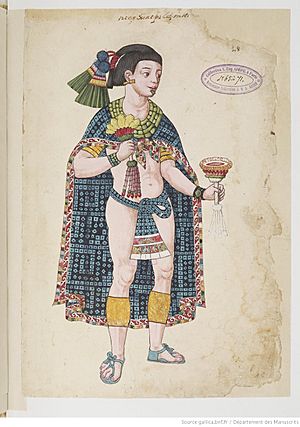

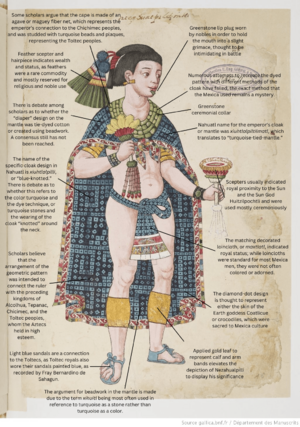

The fourth picture shows the tlatoani Nezahualpilli, who was Nezahualcoyotl's son. This is probably the most famous page in the Codex Ixtlilxochitl. It shows Nezahualpilli's very detailed xiuhtlalpiltilmatl, or "turquoise-tied-mantle." There is some debate about what material this cloak was made from. He also has gold-leaf arm and leg bands, and a maxtlatl (loincloth) with the same pattern as his mantle. He holds feathered incense burners. The image shows Nezahualpilli as a fair and peaceful ruler, which was his reputation. Aztec legends say he could predict the future and foresaw the arrival of the Spanish and the fall of the Aztec Empire under Montezuma II.

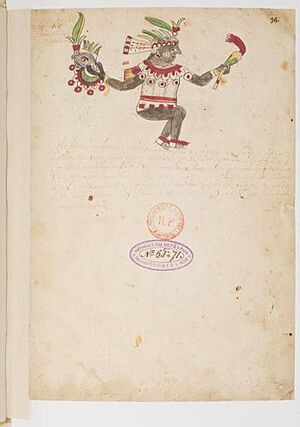

The fifth image is not of an emperor. Instead, it's a detailed picture of the rain god Tlaloc. Tlaloc was very important in Aztec religion because he controlled farming and crops. This picture shows him wearing his usual fanged mask. He holds a lightning bolt in his right hand and a feathered shield in his left.

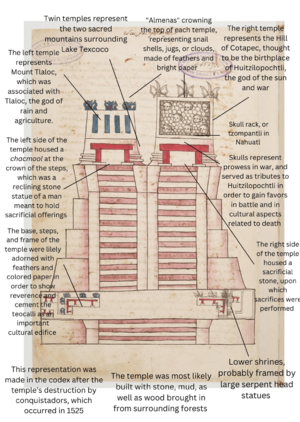

Finally, the sixth image shows Texcoco's great teocalli. This was a pyramid with two temples where many religious ceremonies and cultural events happened. This picture of the teocalli is often confused with Tenochtitlan's Templo Mayor. This is because the artist's lines and colors are very clear. But it is indeed Texcoco's temple. Most Aztec cities had a large central temple for ceremonies. The similarity between Texcoco's and Tenochtitlan's teocallis can sometimes confuse historians.

Section 3: Written Notes

Pages 113 to 122 are notes and written explanations. They are about the Aztec ceremonial calendar that is shown with pictures in the first section. We believe Fernando de Alva Cortez Ixtlilxochitl himself wrote these notes. He likely did this to help Europeans understand Aztec rituals and their calendar dates. The text is simple, written entirely in Spanish. It repeats much of the Spanish notes found in the first section but in a more complete way. It also shares similarities with other written accounts of Aztec calendars by European historians.

Nezahualpilli's Special Cloak

The detailed picture of tlatoani Nezahualpilli's fancy cloak on page 108 gets a lot of attention and discussion. The cloak's "diaper" design, called xiuhtlalpilli, or “blue-knotted” in Nahuatl, has long been a mystery. Historians wonder how it was made and what material was used.

There are two main ideas. One idea, from historian Patricia Anawalt, suggests the design was made on cotton using a tie-dye or batik-like method. However, no one has been able to recreate this successfully. The other idea, from Carmen Aguilera, suggests that the design was made by adding turquoise tiles and beads onto a net base made of plant fiber. This would fit with the very ornate clothes worn by Aztec nobles. Historians have not yet agreed on which idea is more likely. Even the Nahuatl name of the mantle adds to the debate. Anawalt thinks "knotted" refers to the knots made during the dyeing process. Aguilera suggests it refers to how the tiles were attached to the fiber net.

The diamond-dot pattern itself might represent the skin of the earth goddess Coatlicue. Or it could represent the skin of crocodiles, which were sacred to the Aztecs. The way the pattern is arranged refers to patterns from older civilizations like the Alcolhua, Tepanac, Chicimec, and Toltec cultures. These cultures came before the Aztecs and were highly respected.

An Aztec tlatoani was expected to be a direct descendant of the Toltec royal family to become ruler. By wearing a cloak with patterns from these older societies, the emperor showed his connection to the past. This connection gave him a divine right to rule. Also, the simple clothing worn by Ixtlilxochitl I, Nezahualcoyotl, and Nezahualpilli in the codex might refer to the simple style of Toltec culture. It was not until the rule of tlatoani Itzcoatl that the Aztecs had more trade. This allowed them to wear more elaborate clothing. By wearing only the traditional mantle and loincloth for royal ceremonies, they honored the clothing style of their ancestors.

See also

In Spanish: Códice Ixtlilxóchitl para niños

In Spanish: Códice Ixtlilxóchitl para niños

- Texcoco altepetl - the city-state that the Codex Ixtlilxochitl is about

- Fernando de Alva Cortez Ixtlilxochitl - believed to have assembled the codex; a nobleman and historian with Aztec heritage

- Codex Magliabechiano and Codex Tudela - the other two books in the Magliabechiano Group

- Xiuhpohualli - the calendar shown in Section 1 of the Codex Ixtlilxochitl

- Ixtlilxochitl I - a tlatoani of Texcoco, shown on pages 105 and 107

- Nezahualcoyotl - a tlatoani of Texcoco, shown on page 106

- Nezahualpilli - a tlatoani of Texcoco, shown on page 108

- Tlaloc - the rain god, shown on page 110

- Teocalli - the central religious temple, shown on page 112

- Toltec - an ancient Mesoamerican culture that greatly influenced the Aztecs

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |