Mesoamerican literature facts for kids

The traditions of native Mesoamerican literature go way back! They started with the very first types of writing found in the Mesoamerican region. This was around the middle of the first thousand years BCE. Many pre-Columbian cultures in Mesoamerica knew how to read and write. They created many different Mesoamerican writing systems. These writing systems developed on their own, separate from others in the world. This makes them one of the few times writing started from scratch in human history.

Sadly, the Spanish conquerors burned most of the Mesoamerican texts they found. The conquerors also brought their own books from Europe. These new books influenced the native literature.

The writings and texts made by native Mesoamericans are the oldest known from the Americas. This is for two main reasons. First, native Mesoamericans were the first to have a lot of contact with Europeans. This meant many examples of their literature were saved and understood. Second, Mesoamericans had a long history of writing. This helped them quickly learn the Latin alphabet from the Spanish. They then created many new works in this alphabet after the Spanish conquest of Mexico. This article shares what we know about native Mesoamerican writings. It groups them by what they are about and how they were used.

Contents

Ancient Mesoamerican Writings

When we talk about literature, we mean anything that comes from knowing how to read and write. Its main job is to serve a community that uses writing. Here are some types and uses of native Mesoamerican writings we know about.

We can see three main topics in Mesoamerican writings:

- Religion, Time, and Stars: Mesoamerican groups loved to record and track time. They did this by watching the sky and holding religious events for different phases. So, a lot of the Mesoamerican literature we have today is about this. Especially older writings like the Mayan and Aztec codices share calendar and star information. They also describe the rituals linked to time passing.

- History, Power, and Family Lines: Another big part of ancient literature is carved into huge structures. These include stone slabs called stelae, altars, and temples. This writing usually records power and family history. It remembers victories, when rulers took power, and when monuments were dedicated. It also notes marriages between royal families.

- Myths and Stories: We mostly have these from after the Spanish conquest. But they often come from old spoken stories or pictures. The mythical and story-based literature of Mesoamerica is very rich. We can only guess how much has been lost.

- Everyday Writings: Some texts are like everyday notes. These include descriptions of objects and their owners, or carvings on walls. But these are only a very small part of the known writings.

Pictures vs. Words in Writing

Some experts talk about two kinds of writing. One kind uses pictures or symbols that don't need a specific language. Think of road signs; anyone can understand them. This is called 'semasiographical' writing. The other kind is 'glottographic' writing. This uses sounds and words of a language. It lets you read a text exactly the same way every time.

In Mesoamerica, these two types were not separate. Writing, drawing, and making pictures were seen as very similar. In both Mayan and Aztec languages, there was one word for both writing and drawing. Pictures were sometimes read like words. And texts meant to be read sometimes looked very much like pictures.

This makes it hard for today's experts to tell if a carving is spoken language or a drawing. The Maya are the only Mesoamerican people known to have a fully phonetic script. But even their writing often blurs the lines between images and text.

Carvings on Monuments

Carvings on huge monuments were often historical records for city-states. Famous examples include:

- The Hieroglyphic Stair of Copan. It tells the history of Copan with 7,000 symbols on its 62 steps.

- The carvings at Naj Tunich record noble visitors to a sacred cave.

- The tomb carvings of Pacal, the famous ruler of Palenque.

- Many stelae (tall carved stones) from Yaxchilan, Quiriguá, Copán, Tikal, and Palenque.

These historical carvings also helped rulers show their power. They were like propaganda. Most often, these carved texts describe:

- Rulership: When rulers took power or died, and their claims to noble family lines.

- Warfare: Victories and conquests.

- Alliances: Marriages between royal families.

- Dedications: When monuments and buildings were officially opened.

David Stuart, an expert on ancient writings, noted differences in content. For example, carvings at Yaxchilan focused on war, dance, and rituals. They also showed rulers clearly. But Copan's texts focused less on stories. Their stelae mainly named the ruler as the monument's "owner." They rarely recorded rituals or historical events.

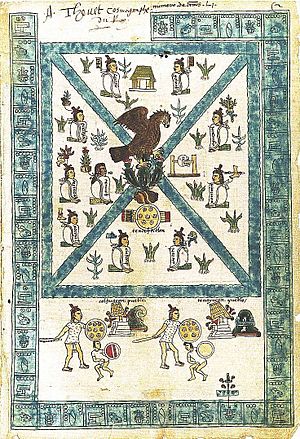

Ancient Books (Codices)

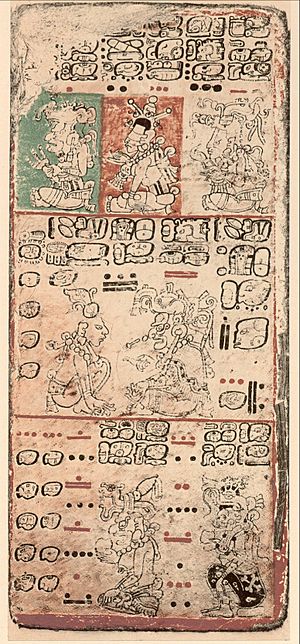

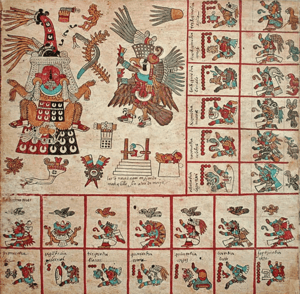

Most codices we have today are from the time after the Spanish conquest. Only a few survived from the time before the Spanish. This is because the conquerors burned many original texts. Some ancient codices, made from amate paper with a white coating, still exist.

- Stories of History

- Mixtec Codices:

* Codex Bodley * Codex Colombino-Becker * Codex Nuttall (tells about the life of ruler Eight Deer Jaguar Claw) * Codex Selden * Codex Vindobonensis

- Aztec Codices

- Texts about Stars, Calendars, and Rituals

- From Central Mexico:

* Codex Borbonicus * Codex Magliabechiano * Codex Cospi * Codex Vaticanus B * Codex Fejérváry-Mayer * Codex Laud

* Paris Codex * Madrid Codex * Dresden Codex * Grolier Codex

Other Ancient Writings

Some everyday items like pottery, bone, and jade ornaments have carvings. For example, drinking cups might say, "The Cacao drinking cup of X."

Writings After the Conquest (in Latin Script)

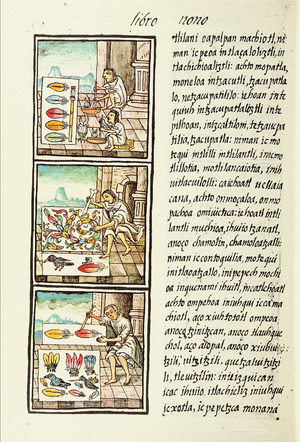

Most Mesoamerican literature we know today was written after the Spanish conquest. Both Europeans and Mayans started writing down local spoken stories. They used the Latin alphabet to write in native languages. This happened soon after the conquest. Many Europeans were priests who wanted to convert natives to Christianity. They translated Catholic books and learned native languages well. They often wrote grammars and dictionaries for these languages. These early language books helped people read and write native languages back then. They also help us understand them today.

The most famous early grammars and dictionaries are for the Aztec language, Nahuatl. Alonso de Molina and Andrés de Olmos wrote important works. But Mayan and other Mesoamerican languages also have early grammars.

Using the Latin alphabet allowed for many new texts. Native writers used these new ways to record their own history and traditions. Monks kept teaching native people to read and write. But this tradition only lasted a few centuries. By the mid-1700s, royal orders made Spanish the only language of the Spanish empire. Most native languages then lost their writing traditions.

However, spoken stories kept being passed down. Experts started collecting them in the early 1900s. Today, it's a big job to bring native language writing back to indigenous peoples. But in the first centuries after the conquest, many texts were created in native Mesoamerican languages.

Important Codices

- Codex Mendoza

- Florentine Codex: This is a huge, twelve-volume work. It was put together by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. It was sent to Europe in 1576. Different books cover Aztec religion, fortune-telling, rulers, merchants, common people, and nature. Volume 12 tells the story of the conquest from the Aztec viewpoint. It's called the "Florentine Codex" because it was found in Florence, Italy.

Historical Stories

Many post-conquest texts are historical accounts. Some are like annals, telling year-by-year events of a people or city-state. These often came from pictures or stories from old community members. Others are personal stories of a people or state. They almost always mix myths and real history. There was no clear difference between the two in Mesoamerica. Sometimes, like in the Mayan Chilam Balam books, historical accounts also included prophecies.

Annals (Year-by-Year Records)

- Annals of the Cakchiquel

- Chilam Balam books from Chumayel, Maní, Tizimin, Kaua, Ixil, and Tusik

- Annals of Tlatelolco, Annals of Tlaxcala, Annals of Cuauhtitlan

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis

- Annals of the Puebla-Tlaxcala Valley

- Many local histories of single native states, in the form of Annals or picture Codices.

Historias (Longer Stories)

- Cronica Mexicayotl by Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc

- Codex Chimalpahin by Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñon Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin

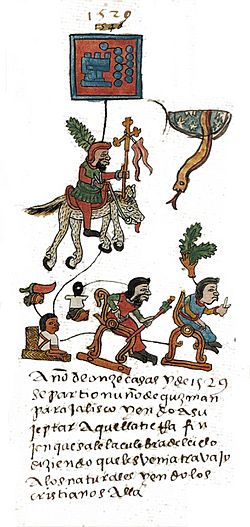

- The Lienzo de Tlaxcala, a picture history of the conquest by Diego Muñoz Camargo

- The Lienzo de Quauhquechollan, another picture history of the conquest

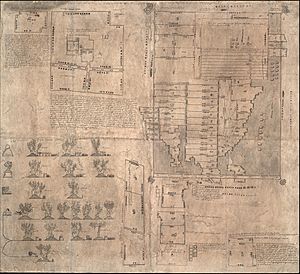

Official Documents

After the conquest, native Mesoamericans had to learn a new government system. To get good positions or prove land ownership, they had to make requests to the new authorities. This led to many official documents in native languages. These documents were often written in the native language first, then translated into Spanish. Historians use these native-language documents a lot.

These official documents include many:

- Testaments: These are legal wills of individuals. They give information about people, families, and how they lived. Many collections of wills have been published.

- Cabildo records: These are records from native town councils. A good example is from Tlaxcala.

- Titulos: These were claims to land and power. They showed a noble family history from before the Spanish arrived.

- Censuses and tribute records: These counted people house by house. They give important details about families, where people lived, and their duties to pay tribute. Important examples are from Cuernavaca, Huexotzinco, and Texcoco.

- Petitions: These were requests, for example, to lower tribute payments. Or they were complaints about unfair lords. A long example is Codex Osuna. It mixes pictures and Nahuatl text to show complaints against colonial officials.

- Land claim documents: These describe land ownership. They were often used in legal cases. The Oztoticpac Lands Map of Texcoco is an example.

Relaciones Geográficas (Geographical Reports)

In the late 1500s, the Spanish crown wanted detailed information. They asked for reports about native settlements in the Spanish Empire. Local Spanish officials gathered information from native towns. They used local leaders as their sources. Some reports were short, like the one from Culhuacan. But some major native groups, like Tlaxcala, gave long descriptions. They told about their history before the Spanish and their role in the Spanish conquest of central Mexico. Most of these reports included a native map of the settlement. The Relaciones geográficas were made because officials followed royal orders. But the information came from native people.

Mythological Stories

The most studied Mesoamerican native literature tells mythological and legendary stories. These books often have a very poetic style. They are appealing because of their beautiful language and "mystical" content. They also help us see connections between cultures. While many include real historical events, mythological texts often focus on claiming a mythical source of power. They trace a people's family line back to some ancient, powerful origin.

- Popol Vuh (the legendary history of the Quiché people)

- Codex Chimalpopoca (the main source for the Aztec creation myth of the Five Suns)

- Codex Aubin (tells about the mythical journeys of the Mexica people)

- Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca (the Aztec myth of the legendary Toltec and Chichimec peoples)

Poetry

Some famous collections of Aztec poetry have been saved. Even though they were written in the late 1500s, they are thought to be quite similar to ancient poetry. Many poems are said to be by Aztec rulers like Nezahualcoyotl. But since the poems were written down much later, experts debate who the real authors were. Many mythical and historical texts also have poetic qualities.

Aztec Poetry

- Cantares Mexicanos

- Romances de los Señores de Nueva España

Mayan Poetry

Theatre

- Rabinal Achí

- Nahuatl Theatre

Ethnographic Accounts (Studies of Cultures)

- Florentine Codex (Bernardino de Sahagún's huge work about Aztec culture, in 12 volumes)

- Coloquios y doctrina Christiana (also called the Bancroft dialogues, describes the first talks between Aztecs and Christian monks)

Mixed Collections

Not all native writings fit neatly into one group. A great example is the Yucatec Mayan Books of Chilam Balam. We mentioned them for their historical content. But they also have writings on medicine, astrology, and more. They are clearly Mayan literature, but they mix many different ideas.

Spoken Stories of the Mesoamericans

- Ethnography of Speaking

- Tradition and changes to them

Folktales

- Fernando Peñalosa

Jokes and Riddles

- Tlacuache stories (Gonzalez Casanova)

Songs

- Henrietta Yurchenco

Nahuatl Songs

- Jaraneros indigenas de Vera Cruz

- Xochipitzahuac

Ritual Speech

- Mayan modern prayers

- Huehuetlahtolli

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |