History of writing facts for kids

Six major historical writing systems (left to right, top to bottom: Sumerian pictographs, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Chinese syllabograms, Old Persian cuneiform, Roman alphabet, Indian Devanagari)

|

The history of writing is all about how people learned to write things down. It shows how systems of marks were created to express language. These marks were used for many different reasons in various societies, changing how people lived and worked together. Writing systems are the base of literacy, which means being able to read and write. This skill has huge impacts on society and how our minds work.

Long ago, before we had full writing systems, there was proto-writing. These were early symbols, like ideographics (pictures representing ideas) or mnemonics (symbols that help you remember things). True writing came later. This is when the exact words someone spoke could be written down so another person could read and understand them accurately. Proto-writing was different because it didn't usually include grammar words or endings, making it hard to know the exact meaning without a lot of background information.

The first uses of writing in ancient Sumeria were for keeping track of farm products and making agreements. But soon, writing was used for money, religion, government, and laws. This helped these activities grow and spread knowledge. It also helped central leaders gain more power. Writing then became the basis for places of learning, like libraries, schools, universities, and scientific research. As writing became more common, different types of writing (called genres) appeared. At first, these genres often showed their social purpose clearly, but over time, their meaning became more obvious, like with money or digital currency.

Contents

- What Makes a Writing System?

- Early History of Writing

- Where and When Writing Began

- How Writing Developed

- Materials for Writing

- How Writing Changed Society

- Images for kids

- See Also

What Makes a Writing System?

Writing systems usually meet three main rules. First, writing must have a clear purpose or meaning. It needs to communicate a message. Second, all writing systems must have a set of symbols. These symbols can be made on any writing material, whether it's physical like paper or digital like a screen. Third, the symbols in a writing system usually copy spoken words or speech. This makes communication possible.

Symbolic systems are different from writing systems. With writing, you usually need to understand the spoken language it represents to understand the text. But symbolic systems, like information signs, paintings, maps, and mathematics, often don't need you to know a spoken language beforehand.

Every human group has a language. While we don't fully know how language started, it's a basic part of being human. However, writing systems didn't develop everywhere at the same time. They appeared slowly and unevenly. Once writing systems were set up, they generally changed slower than spoken languages. They often kept old features and expressions that were no longer used in everyday talk.

The biggest benefit of writing is that it helps societies record information. It allows for more detail and consistency than spoken words ever could. Writing lets societies pass on information and share and keep knowledge for future generations.

Early History of Writing

Some early signs, found next to animal pictures, might be the first proto-writing. They appeared in Europe around 35,000 BCE during the Upper Palaeolithic period. These symbols might have been used together to share information about animals' seasonal behavior.

The start of writing is generally linked to the pottery-making period of the Neolithic Age. During this time, people used clay tokens to record specific amounts of animals or goods. These tokens were first pressed onto the outside of round clay envelopes. Then, they were stored inside. Over time, flat tablets replaced the tokens. Signs were written on these tablets with a pointed tool called a stylus.

True writing first appeared in Uruk, at the end of the 4th millennium BCE. Soon after, it showed up in other parts of the Near East.

An old Mesopotamian poem tells the first known story of how writing was invented:

Because the messenger's mouth was heavy and he couldn't repeat (the message), the Lord of Kulaba patted some clay and put words on it, like a tablet. Until then, there had been no putting words on clay.

Experts often separate the "prehistory" of writing from "history." But they don't always agree on when proto-writing became "true writing." The difference is mostly a matter of opinion. Generally, writing is a way to record information using graphemes (basic units of a writing system), which can be made of glyphs (individual marks).

When writing first appears in an area, it's usually seen in small, broken pieces for several centuries. Historians say a culture has "history" when it has clear, complete texts written in its own writing system.

Where and When Writing Began

For a long time, people thought writing was invented in only one place. This idea was called "monogenesis." Scholars believed all writing started in ancient Sumer (in Mesopotamia). From there, it spread around the world through cultural diffusion. This theory suggested that the idea of writing down language, even if not the exact system, was passed on by traders.

However, scholars later learned about the writing systems of ancient Mesoamerica. These were far from the Middle East, proving that writing had been invented more than once. Today, experts believe writing developed independently in at least four ancient civilizations:

- Mesopotamia (between 3400 and 3100 BCE)

- Egypt (around 3250 BCE)

- China (1200 BCE)

- Lowland areas of Mesoamerica (by 500 BCE)

For ancient Egypt, some scholars say that the first clear evidence of Egyptian writing looks different from Mesopotamian writing. So, it must have developed on its own. It's possible that the *idea* of writing came from Mesopotamia, but the Egyptian system itself was unique.

For China, it's believed that ancient Chinese characters were invented independently. There's no proof of contact between ancient China and the writing cultures of the Near East. Also, the Chinese way of using logograms (symbols for whole words) and phonetic sounds is very different from Mesopotamia's.

There's still debate about the Indus script from the Bronze Age Indus Valley civilisation, the Rongorongo script of Easter Island, and the Vinča symbols from around 5500 BCE. These are all undeciphered. So, we don't know if they are true writing, proto-writing, or something else entirely.

The Sumerian archaic (pre-cuneiform) writing and Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally seen as the earliest true writing systems. Both grew out of older symbol systems between 3400 and 3100 BCE. The first clear texts from these systems appeared around 2600 BCE. The Proto-Elamite script is also from this same time.

How Writing Developed

Writing usually goes through several steps from "proto-writing" to "true writing":

- Picture writing system: Simple pictures (glyphs) directly show objects and ideas.

- Mnemonic: Glyphs mainly serve as reminders.

- Pictographic: Glyphs directly show an object or idea. For example, a drawing of a sun means "sun."

- Ideographic: Symbols are abstract and represent an idea or concept. For example, a symbol might mean "love" or "justice."

- Transitional system: Symbols refer to both the object or idea they show and its name.

- Phonetic system: Symbols refer to sounds or spoken words. The symbol's shape doesn't relate to its meaning.

- Verbal: A symbol (logogram) represents a whole word.

- Syllabic: A symbol represents a syllable (a part of a word, like "ba" or "le").

- Alphabetic: A symbol represents a basic sound (like 'a' or 'b').

Some well-known early picture writing systems with ideographic or mnemonic symbols include:

- Jiahu symbols: Carved on tortoise shells in Jiahu, around 6600 BCE.

- Vinča symbols (Tărtăria tablets): Around 5300 BCE.

- Early Indus script: Around 3100 BCE.

In the Old World, true writing systems grew from neolithic writing during the Early Bronze Age (4th millennium BCE).

Proto-Writing Systems

The first writing systems of the Early Bronze Age didn't appear suddenly. They grew from older symbol systems that weren't quite proper writing but had many writing-like features. These are called "proto-writing." They used ideographic or early mnemonic symbols to share information. However, they probably didn't directly represent a natural language.

These systems started in the early Neolithic period, as early as the 7th millennium BCE. They include:

- The Jiahu symbols: Found carved in tortoise shells in China, dating from the 7th millennium BCE. Most archaeologists don't think these are directly linked to the first true writing.

- Vinča symbols: Also called the "Danube script," these symbols are found on Neolithic era objects (6th to 5th millennia BCE) from the Vinča culture in Central Europe and Southeast Europe.

- The Dispilio Tablet: From the late 6th millennium, it might also be an example of proto-writing.

- The Indus script: Used from about 3500 BCE to 1900 BCE for very short writings.

Even after the Neolithic period, some cultures used proto-writing before developing proper writing. The quipu of the Incas (15th century CE), sometimes called "talking knots," might have been one such system. Another example is the pictographs invented by Uyaquk around 1900 for the Central Alaskan Yup'ik language, before its syllabary was developed.

Bronze Age Writing Systems

Writing appeared in many different cultures during the Bronze Age. Examples include cuneiform writing in Sumer, Egyptian hieroglyphs, Cretan hieroglyphs, Chinese logographs, Indus script, and the Olmec hieroglyphs of pre-Columbian era Mesoamerica. Chinese characters likely developed on their own, separate from Middle Eastern scripts, around 1600 BCE. The Mesoamerican writing systems (like Olmec and Maya script) are also generally thought to have started independently.

The first true alphabetic writing is believed to have developed around 2000 BCE. It was created for Semitic-speaking workers in the Sinai Peninsula. They adapted Egyptian Hieratic letters to represent Semitic sounds (see history of the alphabet and Proto-Sinaitic script). The Geʽez script of Ethiopia and Eritrea grew from the Ancient South Arabian script.

Most other alphabets in the world today either came from this one invention, often through the Phoenician alphabet, or were directly inspired by it.

Cuneiform Script

The original Sumerian writing system came from a system of clay tokens used to represent goods. By the end of the 4th millennium BCE, this became a way to keep accounts. People used a round stylus to press marks into soft clay at different angles to record numbers. This slowly grew to include pictographic writing, using a sharp stylus to show what was being counted.

By 2900 BCE, writing, at first only for logograms (symbols for whole words), used a wedge-shaped stylus. This is where the name cuneiform comes from. This new method slowly replaced the round and sharp stylus writing by around 2700–2500 BCE. Around 2600 BCE, cuneiform started to represent syllables of the Sumerian language. Finally, cuneiform became a general writing system for words, syllables, and numbers. From the 26th century BCE, this script was adapted for the Akkadian language, and then for others like Hurrian and Hittite.

Egyptian Hieroglyphs

Writing was very important for keeping the Egyptian empire running. Reading and writing skills were mostly held by an educated group of scribes. Only people from certain backgrounds could train as scribes. They worked for temples, the royal family (pharaohs), and the military.

Some scholars believe Egyptian hieroglyphs appeared a little after Sumerian script. They might have been influenced by the Sumerian system. However, there is no clear proof that Egyptian hieroglyphs directly copied Mesopotamian writing. Some argue that Egyptian writing developed on its own.

Since the 1990s, glyphs found at Abydos date back to between 3400 and 3200 BCE. These discoveries might challenge the idea that Mesopotamian symbols came first. Egyptian writing seems to appear suddenly around that time, while Mesopotamia has a longer history of using signs in tokens, going back to about 8000 BCE. These glyphs from Abydos are on ivory and were likely labels for goods in a tomb.

Chinese Writing

The earliest clear evidence of Chinese writing is found on oracle bones and bronze from the late Shang dynasty. The oldest of these date to around 1200 BCE.

Recently, tortoise-shell carvings from around 6000 BCE have been found, like the Jiahu Script. However, it's debated whether these carvings are complex enough to be considered true writing. At Damaidi in the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, over 3,000 cliff carvings from around 6000–5000 BCE have been discovered. They show over 8,000 individual characters, like the sun, moon, and hunting scenes. These pictures are said to be similar to the earliest confirmed Chinese characters. If they are indeed a written language, writing in China would be 2,000 years older than Mesopotamian cuneiform. However, it's more likely that these inscriptions are a form of proto-writing, similar to the European Vinca script of the same time.

Cretan and Greek Scripts

Cretan hieroglyphs are found on objects from Crete (early to mid-2nd millennium BCE). They overlap with Linear A. Linear B, the writing system of the Mycenaean Greeks, has been figured out. However, Linear A has not yet been deciphered.

Here's how these writing systems spread over time and place:

| Writing system | Geographical area | Time span |

|---|---|---|

| Cretan Hieroglyphic | Crete (eastward from the Knossos-Phaistos axis) | c. 2100−1700 BCE |

| Linear A | Crete (except extreme southwest), Aegean Islands (Kea, Kythera, Melos, Thera), and Greek mainland (Laconia) | c. 1800−1450 BCE |

| Linear B | Crete (Knossos), and mainland (Pylos, Mycenae, Thebes, Tiryns) | c. 1450−1200 BCE |

Mesoamerican Writing

A stone slab with 3,000-year-old writing, called the Cascajal Block, was found in Mexico. It is the oldest script in the Western Hemisphere. It came before the oldest Zapotec writing, which dates to about 500 BCE.

Among several pre-Columbian scripts in Mesoamerica, the Maya script seems to have been the most developed and has been fully deciphered. The earliest clear Maya writings are from the 3rd century BCE. Writing was used continuously until shortly after the Spanish arrived in the 16th century CE. Maya writing used logograms (symbols for whole words) along with a set of syllable symbols. This is somewhat similar to modern Japanese writing.

Iron Age Writing

The Phoenician alphabet is simply the Proto-Canaanite alphabet as it continued into the Iron Age (starting around 1050 BCE). This alphabet led to the Aramaic and Greek alphabets. These, in turn, led to the writing systems used across Western Asia, Africa, and Europe. The Greek alphabet was the first to include clear symbols for vowel sounds.

The Greek and Latin alphabets in the early centuries CE led to several European scripts like the Runes, the Gothic, and Cyrillic alphabets. The Aramaic alphabet developed into the Hebrew, Arabic, and Syriac abjads. The Syriac script spread as far as Mongolian script. The South Arabian alphabet led to the Ge'ez abugida. Some scholars believe the Brahmic family of scripts in India also came from the Aramaic alphabet.

Grakliani Hill Writing

In 2015, a new script was found in Georgia, on Grakliani Hill. It was just below a temple's altar from the seventh century BCE. These writings are different from others at Grakliani, which show animals or people. The script doesn't look like any known alphabet, though its letters might be related to ancient Greek and Aramaic. It seems to be the oldest native alphabet found in the whole Caucasus region. For comparison, the earliest Armenian and Georgian script are from the fifth century CE.

In 2016, the Grakliani Hill writings were tested. It was found that they were made around 1005–950 BCE.

Writing in Ancient Greece and Rome

The history of the Greek alphabet began in at least the early 8th century BCE. The Greeks adapted the Phoenician alphabet for their own language. The letters of the Greek alphabet are very similar to those of the Phoenician alphabet, and they are arranged in the same order. The Greeks added three new letters to the end of the alphabet.

Several types of the Greek alphabet developed. One, called Western Greek, was used west of Athens and in southern Italy. The other, called Eastern Greek, was used in modern-day Turkey and by the Athenians. Eventually, the rest of the Greek-speaking world adopted the Eastern Greek version.

At first, the Greeks wrote from right to left, like the Phoenicians. But they eventually chose to write from left to right. Sometimes, they used "boustrophedon" writing. This meant they would start the next line where the previous one ended, so lines would go alternately left-to-right, then right-to-left. This was like an ox plowing a field. This style was used until the sixth century BCE.

Italic Scripts and Latin

Greek writing is the source for all modern European scripts. The most common one is the Latin script. It's named after the Latins, a group in central Italy who became powerful with the rise of Rome. The Romans learned to write around the 5th century BCE from the Etruscan civilization. The Etruscans used one of several Italic scripts that came from the western Greeks. Because the Roman state became so dominant, most other Old Italic scripts didn't survive, and the Etruscan language is mostly lost.

Writing in the Middle Ages

When the Roman power fell in Western Europe, writing mostly continued to develop in the Eastern Roman Empire and the Persian Empire. Latin, which was never a main literary language, quickly became less important, except within the Roman Catholic Church. The main literary languages were Greek and Persian. Other languages like Syriac and Coptic were also important.

The rise of Islam in the 7th century quickly made Arabic a major literary language. Arabic and Persian soon became more important for scholarship than Greek. Arabic script was adopted as the main script for Persian and Turkish. This script also greatly influenced the development of cursive scripts for Greek, Slavic languages, Latin, and others. The Arabic language also helped spread the Hindu–Arabic numeral system across Europe. By the start of the second millennium, the city of Córdoba in modern Spain was a top intellectual center. It had the world's largest library at the time. Its location, connecting the Islamic and Western Christian worlds, helped boost intellectual growth and written communication between both cultures.

Renaissance and Modern Writing

By the 14th century, a rebirth, or renaissance, began in Western Europe. This led to a temporary return of Greek's importance and a slow comeback for Latin as a key literary language. A similar, though smaller, rise happened in Eastern Europe, especially in Russia. At the same time, Arabic and Persian slowly became less important as the Islamic Golden Age ended.

The renewed focus on reading and writing in Western Europe led to many new ideas for the Latin alphabet. The alphabet became more diverse to represent the sounds of different languages.

The way we write has always changed, especially with new technologies. The pen, the printing press, the computer, and the mobile phone have all changed what we write and how we produce written words. With digital technologies like computers and phones, you can form characters by pressing a button, instead of moving your hand.

Materials for Writing

We don't know for sure what material was most commonly used for writing when early systems began. Throughout history, people have engraved on stone, metal, or other strong materials to make records last. Metals like stamped coins were used for writing, including lead, brass, and gold. People also engraved gems, like for seals or signets.

Common writing materials were the tablet and the roll. Tablets probably came from Chaldea, and rolls from Egypt. Chaldean tablets were small pieces of clay, shaped roughly like pillows. They were thickly covered with cuneiform characters. Similar uses were seen with hollow cylinders or prisms made of fine terracotta. Characters were traced on them with a small stylus, sometimes so tiny that a magnifying glass was needed.

In Egypt, the main writing material was very different. Wooden tablets are shown in ancient pictures. But the most common material, even from very old times, was papyrus. It was used as far back as 3,000 BCE. This reed, found mainly in Lower Egypt, had many economic uses for writing. The soft inner part was taken out and divided into thin pieces. These were then flattened by pressing them and glued together. Other strips were placed at right angles to them, so a roll of any length could be made. Writing seems to have become more common with the invention of papyrus in Egypt.

Because papyrus was in high demand and sent all over the world, it became very expensive. Other materials were often used instead, like leather. A few early leather scrolls have been found in tombs. Parchment, made from sheepskins after the wool was removed, was sometimes cheaper than papyrus, which had to be imported outside Egypt. With the invention of wood-pulp paper, the cost of writing material steadily dropped. Wood-pulp paper is still used today.

How Writing Changed Society

Writing and the Economy

Writing started with counting and listing farm products, and then with money transactions. Government tax records followed. Written documents became vital for people, the state, and religious groups to gather and keep track of wealth. They also helped with trade, loans, inheritance, and proving ownership. With these documents, larger amounts of wealth could be gathered, along with the power that came with it. This especially benefited royalty, the state, and religions.

Contracts and loans helped long-distance international trade grow. This supported networks for importing and exporting goods, which helped capitalism rise. Paper money (first seen in China in the 11th century CE) and other financial tools relied on writing. At first, this was in the form of letters, then it became specialized documents. These documents explained the transactions and guarantees of value from people, banks, or governments.

As economic activity grew in late Medieval and Renaissance Europe, advanced ways of accounting and calculating value appeared. These calculations were done in writing and explained in manuals. The creation of corporations then led to many documents about organization, management, sharing of shares, and record-keeping.

Writing and Religion

The creation of sacred religious texts or scriptures, often said to be from a divine source, created clear belief systems. These texts became the basis of the modern idea of religion. Copying and spreading these texts helped these religions and their beliefs spread. So, they were central to convincing new followers. These sacred books made it a duty for believers to read them, or to follow the teachings of priests who were in charge of reading, explaining, and applying these texts.

Famous examples of such scriptures are the Torah, the Bible (with its many books), the Quran, the Vedas, the Bhaghavad Gita, and the Sutras. But there are many more religious texts throughout history. These texts, because they spread widely, tended to create general guides for good behavior. These guides were for all members of the religious community, and often for all humans, like the Ten Commandments.

Writing and Law

Private legal documents for selling land appeared in Mesopotamia in the early third millennium BCE, soon after cuneiform writing began. The first written legal codes followed around 2100 BCE. The most famous is the Code of Hammurabi, carved on stone pillars in Babylon around 1750 BCE. While Ancient Egypt didn't have written laws, legal orders and private contracts appeared in the Old Kingdom around 2150 BCE. The Torah, or the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, especially Exodus and Deuteronomy, wrote down the laws of Ancient Israel. Many other law codes followed in Greece and Rome. Roman law later became a model for church law and secular law across much of Europe.

In China, the earliest signs of written laws or punishment books are inscriptions on bronze vessels from 536 BCE. The oldest full set of laws we have is from the Qin and Han Dynasties. These laws created a complete system of social control and government. They included criminal procedures and rules for both government officials and citizens. These laws needed complex reporting and documenting to help with supervision from villages up to the emperor.

In England, Common Law developed mostly through spoken traditions after the Romans left. But with the return of the church and then the Norman invasion, customary law and court decisions began to be written down. However, many parts remained oral. Documents only recorded public promises, wills, land transfers, court judgments, and ceremonies. During the late Medieval period, documents gained authority for agreements, transactions, and laws.

When the United States was founded, laws were created as written rules within codes. They were controlled by central documents, including the federal and state Constitutions. All these legislative documents were printed and shared. Also, court decisions were written down and published. These then served as examples for future judgments in states and nationwide. Courts of Appeals in the United States only look at documents from earlier proceedings and judgments. They do not take new spoken evidence.

Writing and Government

Writing has been key to expanding many government functions. These include laws, rules, taxes, and keeping records of citizens. All these depend on the growth of bureaucracy, which creates and manages rules and keeps records. These developments, which rely on writing, increase the power and reach of states.

At the same time, writing has helped citizens learn about how the government works. It has helped them organize to express their needs and concerns. It has also helped people feel connected to their regions and states. The rise of journalism is closely linked to informing citizens, creating regional and national identity, and expressing interests. These changes have greatly influenced states, making people and their views more visible, no matter the type of government.

Large bureaucracies grew in the ancient Near East and China. They relied on educated groups of scribes and bureaucrats. In the Ancient Near East, this happened through scribal schools. In China, it led to written imperial examinations based on classic texts. These exams effectively controlled education for thousands of years. Being able to read and write remained linked to rising in government. Printing, when it appeared, was tightly controlled by the government. Common language texts only appeared later and were limited until the early twentieth century.

In ancient Greece and Rome, differences between citizens and slaves, rich and poor, limited education and participation. In Medieval and early modern Europe, the church controlled education. This showed the importance of religion in controlling the state and its bureaucracies.

In Europe and the American colonies, the invention of the printing press and cheaper paper allowed ordinary citizens to get more information about the government. The Reformation, which emphasized individual reading of sacred texts, eventually spread reading skills beyond the ruling classes. This opened the door to wider knowledge and criticism of government actions. Divisions in English society during the sixteenth century and the Civil War of the seventeenth century were accompanied by many written pamphlets.

Newspapers and journalism, which started with business information, soon offered political news. They were important in forming a public sphere. Newspapers were key in sharing information, encouraging discussion, and forming political identities during the American Revolution and in the new nation. The spread of newspapers also created urban, regional, and state identities in the late nineteenth century. A focus on national news, helped by the telegraph and national newspapers, also shaped what people paid attention to throughout the twentieth century.

One of the earliest known named people in writing is Kushim, from the Uruk period.

Writing and Knowledge

Much of what we know is written down. It comes from groups and institutions working together to create, share, and evaluate texts. These groups are often called disciplines, and their products are disciplinary literatures. Writing made it easier to share, compare, and critique texts. This made knowledge more widely available across different places and times.

Sacred scriptures formed the common knowledge of religions based on texts. Knowing these scriptures became the focus of religious institutions, interpretation, and schooling. Other parts of this article discuss knowledge specific to the economy, law, and government. This section focuses on the development of non-religious knowledge and its related social groups, institutions, and educational practices.

Knowledge in Ancient Civilizations

In Mesopotamia and Egypt, scribes became important beyond their roles in economy, government, and law. They became the creators and guardians of astronomy, calendars, and literature. Schools developed in tablet houses, which also stored knowledge. In ancient India, the Brahman caste became guardians of texts that collected and organized oral knowledge. These texts then became the official basis for continued oral education. For example, Pāṇini, a linguist, analyzed and organized knowledge of Sanskrit grammar. Mathematics, astronomy, and medicine were also subjects of classic Indian learning and were written down in classic texts. Less is known about Mayan, Aztec, and other Mesoamerican learning because the conquistadors destroyed many texts. But we know that scribes were respected, elite children went to schools, and the study of astronomy, map making, history, and family trees flourished.

Knowledge in China

In China, after the Qin dynasty tried to remove all traces of the Confucian tradition, the Han dynasty made knowledge of ancient texts a requirement for government jobs. This was to bring back knowledge that was almost lost. The Imperial civil service examination system, which lasted for two thousand years, was a written exam based on knowledge of classical texts. To help students get government jobs through this exam, schools focused on these same texts. These texts covered philosophy, religion, law, astronomy, mathematics, military, and medical knowledge. Printing, when it appeared, mostly served the needs of the government and monasteries. Widespread printing in common languages only appeared around the fifteenth century CE.

Knowledge in Ancient Greece and Rome

Ancient Greece produced much written knowledge that influenced Western learning for two thousand years. Even though Plato thought writing was not as good as speaking for learning, we know his works through Socrates' written accounts of his dialogues. Scholars believe the philosophical works of Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle came about because of writing. Writing allowed people to compare ideas from different regions and develop systematic critical thinking by examining documents and writing clear accounts. Aristotle wrote books and lectures that were central to education at the Lyceum, along with the many books in its library. Other philosophers also wrote and taught in Athens, though we only have parts of their works now.

Greek writers started many other fields of knowledge. Herodotus and Thucydides, writing in the fifth century BCE in Athens, are considered the founders of history. They changed family trees and myths into systematic investigations of events. Thucydides developed a more critical, neutral history by examining documents, writing down speeches, and doing interviews. Hippocrates wrote several major medical works during the same period, organizing and advancing medical knowledge. In the second century CE, the Greek-trained doctor Galen went to Rome. He wrote many works that were dominant in European medicine through the Renaissance. Greek writers in Egypt also created collections of knowledge using the resources of the great library at Alexandria. For example, Euclid's Elements of geometry is still a standard reference today. Ptolemy's work on astronomy was dominant through the Middle Ages.

Scholars in Rome continued to write collections of knowledge, including Varro, Pliny the Elder, and Strabo. While Romans were great at building, Vitruvius documented much of their building practices, which still influence design today. Agriculture also became an important area for manuals. Many manuals on public speaking and education appeared, which influenced future generations.

Islamic Learning

With the fall of Rome, the Middle East became a center for learning. Knowledge from the West and East met in Byzantium, Damascus, and then Baghdad. In Baghdad, a research institute (or House of Wisdom) with a large library was founded. Greek works on medicine, philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy were translated into Arabic, along with Indian works on mathematics and treatments. Philosophers like Al-Kindi and Avicenna and astronomers like Al-Farqhani added new ideas to these texts. Al-Kharazami wrote the first book on algebra, using both Greek and Indian sources. The importance of the Quran to the new Islamic religion also led to the growth of Arabic Linguistics.

From Baghdad, knowledge and texts flowed back to South Asia and down through Africa. A large collection of books and an educational center grew around the Sankhore Mosque in Timbuktu, the capital of the Songhai Empire. During this time, the Abbasid Caliphate moved its center of power and learning to Córdoba, in Spain. There, they founded a major library that brought many classic texts back into Europe, along with Arabic learning.

Early Universities in Europe

The reintroduction of classic texts into Europe through the library and intellectual culture in Córdoba, including works by Plato, Aristotle, Euclid, Ptolemy, and Galen, along with Arabic texts, created a need for explanation, lectures, and scholarship. This was to make these works easier for scholars in monasteries and cities to access. During the twelfth century, universities grew from groups of scholars in Italy (Bologna), Spain (Salamanca), France (Paris), and England (Oxford). By 1500, there were at least sixty universities across Europe, with at least three-quarters of a million students. Each of the four main subjects (Liberal Arts, Theology, Law, and Medicine) focused on passing on classic texts, rather than creating new knowledge beyond lectures and comments. This type of education continued well into the seventeenth century.

Printing and the Growth of Knowledge in Europe Johannes Gutenberg’s introduction of the moveable type printing press in Europe around 1450 created new chances to produce and widely share books. This led to much new writing, especially for the development of knowledge. Producing and sharing knowledge was no longer tied to monasteries or universities with their libraries and handwritten copies. In the centuries that followed, Europe was politically and religiously divided. No single authority could censor or control book production. While universities still focused on old texts, publishing houses became new centers of knowledge. Publishing houses in different areas meant many different ideas became available as books moved across borders. Scholars began to see themselves as citizens of a "Republic of Letters."

Comparing many editions of old texts led to better textual scholarship. The ability to share and compare results from many regions and involve more people in science soon led to the development of early modern science. Medical books began to include observations from current surgeries and dissections, including printed pictures, to improve knowledge of anatomy. With many copies of old and new books appearing, debates arose over their value. Maps and discoveries from exploration and colonization were also recorded in books and government records. This was often for economic gain, but also to satisfy curiosity about the world.

Printing also made possible the invention of scientific journals. The Journal des sçavans appeared in France and The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in England, both in 1665. Over the years, these journals grew and became the basis of academic fields and their literatures. Different types of writing for reporting experiments and theories developed, leading to modern ways of publishing scientific work. The availability of scientific books and journals also helped develop modern practices of scientific reference and citation. These changes from printing contributed to the scientific revolution and the science in the Age of Enlightenment.

Modern Research University and Writing

In the eighteenth century, some Scottish and English universities began offering more practical and modern studies. They taught rhetoric and writing to help their non-elite students influence current events. However, it was only in the nineteenth century that universities in some countries started to create space for writing new knowledge. This changed them from mainly sharing old knowledge to becoming places focused on both reading and writing. The creation of research seminars and papers in history and language studies in German Universities was a key starting point for university reform. Professorships in many fields appeared over the century. The German model of a research university influenced how universities were organized in England and the United States. In elite British universities, writing instruction was supported by the tutorial system, with students writing weekly for their tutors. In the United States, regular writing courses were often required starting in the late nineteenth century.

Military Knowledge and Secret Documents

Military knowledge of strategies and tools goes back to ancient Egypt, India, China, Greece, and Rome. There were historical accounts and manuals for warfare. After printing came to the West, manuals for building forts and battle strategies were widely copied, as nations were often fighting. However, with the growth of chemistry and other sciences, knowledge of new weapons was often kept in secret documents. Other documents about policies, production, and distribution of new weapons also developed.

By World War I, both sides used new technologies based on science for military purposes, especially chemical weapons. Over 5000 scientists worked on developing weapons, while trying to limit access to information in secret documents. The push for secret knowledge, including new research, became very strong with the race to develop nuclear weapons in World War II, like in the U.S. Manhattan Project. Aviation, rockets, radar, encryption, and computing were also subjects of classified documents. This system of classifying knowledge continued after WWII ended as the Cold War began.

Literature and Writing

The history of literature began after writing developed in Sumer. At first, writing was used for accounting. The very first writings from ancient Sumer were not literature. The same is true for some early Egyptian hieroglyphics and thousands of ancient Chinese government records. Scholars disagree about when written record-keeping became more like literature. But the oldest surviving literary texts are from a thousand years after writing was invented.

The earliest known literary author by name is Enheduanna. She is credited with several Sumerian literary works, including Exaltation of Inanna, in the Sumerian language during the 24th century BCE. The next earliest named author is Ptahhotep. He wrote The Maxims of Ptahhotep, an instruction book for young men in Egyptian, composed in the 23rd century BCE. The Epic of Gilgamesh is an early famous poem. But it can also be seen as a political celebration of the historical King Gilgamesh of Sumer.

How Writing Changes Our Minds

Walter Ong, Jack Goody, and Eric Havelock were among the first to argue that reading and writing have psychological and intellectual effects. Ong said that writing changed human consciousness. Instead of just hearing spoken words, people could now critically examine and organize words that were written down. Havelock believed that Greek philosophical thought came from using written words. This allowed people to compare beliefs and critically examine ideas. Jack Goody argued that written language encouraged practices like categorizing, making lists, following formulas, and recording experiments. These practices changed how people thought and behaved.

While recognizing these possible changes, Sylvia Scribner and Michael Cole argued that these changes didn't happen to everyone or automatically with literacy. Instead, they depended on how literacy was used in local situations. They studied the Vai people of West Africa. For them, the psychological effects of literacy varied because locals learned to read and write the Vai language, English, and Arabic in three different ways: practical skills, secular education, and religious education.

European language literacy was linked to European-style schooling. It helped with things like logical reasoning. Arabic literacy was linked to religious training and helped with memorization. Literacy in written Vai, used for daily tasks, improved understanding of what an audience knows and needs.

In a different study, James Pennebaker and his team found that writing about difficult experiences can reduce anxiety, improve mental well-being, and even improve physical health.

Images for kids

-

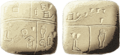

Clay bulla and tokens, 4000–3100 BCE, Susa

-

Numerical tablet, 3500-3350 BCE (Uruk V phase), Khafajah

-

Pre-cuneiform tags, with drawing of goat or sheep and number (probably "10"), Al-Hasakah, 3300–3100 BCE, Uruk culture

-

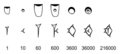

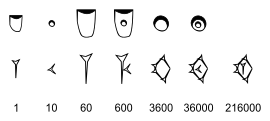

Early Proto-cuneiform (4th millennium BCE) and cuneiform signs for the sexagesimal system (60, 600, 3600, etc.).

-

Art of Lascaux, with painted animal, and four dots, a possible notation for Lunar months.

-

The Kish tablet from Sumer, with pictographic writing. This may be the earliest known writing, 3500 BCE. Ashmolean Museum

-

Sumer, an ancient civilization of southern Mesopotamia, is believed to be the place where written language was first invented around 3200 BCE

-

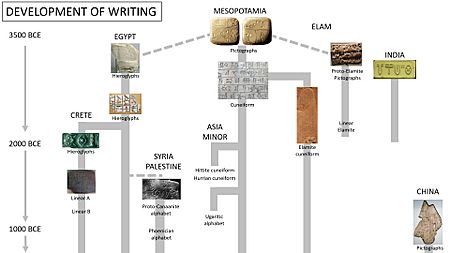

Standard reconstruction of the development of writing. There is a possibility that the Egyptian script was invented independently from the Mesopotamian script. This diagram excludes the writing systems found in Mesoamerica by 500 BCE.

-

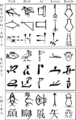

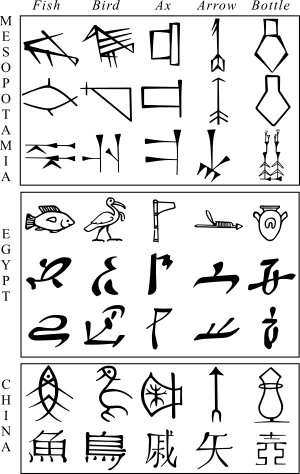

Comparative evolution from pictograms to abstract shapes, in Mesopotamian Cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters

-

Tablet with proto-cuneiform pictographic characters (end of 4th millennium BCE), Uruk III

-

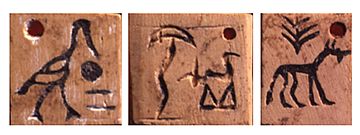

Designs on some of the labels or tokens from Abydos, carbon-dated to circa 3400–3200 BCE and among the earliest form of writing in Egypt. They are remarkably similar to contemporary clay tags from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

-

Indus script tablet recovered from Khirasara, Indus Valley Civilization

-

The sculpture depicts a scene where three soothsayers are interpreting to King Suddhodana the dream of Queen Maya, mother of Gautama Buddha. Below them is seated a scribe recording the interpretation. From Nagarjunakonda, 2nd century CE.

-

Early Greek alphabet on pottery in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

-

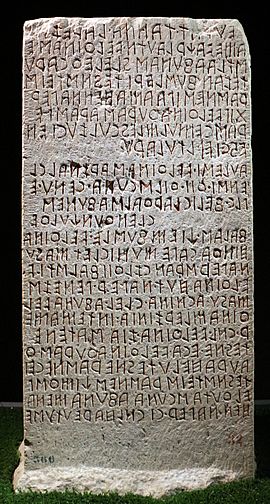

Cippus Perusinus, Etruscan writing near Perugia, Italy, the precursor of the Latin alphabet

See Also

In Spanish: Historia de la escritura para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la escritura para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |