History of printing facts for kids

The story of printing began a very long time ago, around 3000 BCE. Ancient civilizations like the proto-Elamites and Sumerians used special cylinder seals to mark important documents made of clay. Other early ways of printing included block seals, designs on coins, patterns on pottery, and printing on cloth.

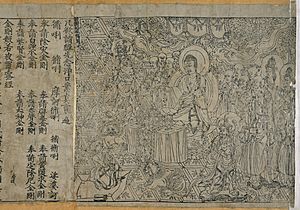

At first, printing was used to put patterns on fabrics like silk. But by the 7th century, in China during the Tang dynasty, people started using woodblock printing to print texts on paper. This helped books spread across Asia, including Korea and Japan. The oldest known printed book with a clear date is the Chinese Buddhist Diamond Sutra, printed using woodblocks on May 11, 868.

Later, in the 11th century during the Song dynasty, a Chinese craftsman named Bi Sheng invented movable type. This meant individual characters could be moved around to form new words and sentences. However, woodblock printing was still more common in China. But metal movable types were used for printing paper money in 1161. The idea of movable type also reached other places. The oldest existing book printed with metal movable type is the Jikji, made in Korea in 1377 during the Goryeo era.

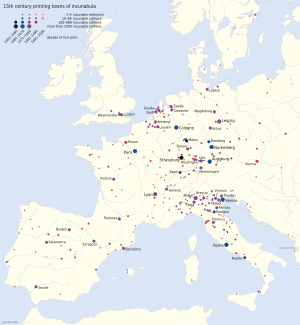

In Europe, woodblock printing was also used until the mid-1400s. Then, a German inventor named Johannes Gutenberg created the first printing press. It was based on older mechanical presses and a new way to make metal type. By the end of the 15th century, Gutenberg's invention, especially his famous Gutenberg Bible, helped create a big book publishing business across Renaissance Europe. This new way of printing allowed ideas and knowledge to be shared much faster than ever before. It led to the global spread of the printing press in the early modern period. Along with text printing, new ways to copy images cheaply, like lithography, screen printing, and photocopying, also developed.

Contents

- Stenciling: Early Art and Patterns

- Brick Stamps: Naming Ancient Buildings

- Seals: Ancient Signatures and Symbols

- Stone, Clay, and Bronze Blocks: Printing on Fabric

- Woodblock Printing: Books and Art

- Movable Type: Individual Letters for Printing

- European Movable Type: Gutenberg's Revolution (1439)

- Intaglio Printing: Ink in Grooves

- Lithography: Printing with Chemicals (1796)

- Color Printing: Adding Hues to Prints

- Offset Press: Indirect Printing (1870s)

- Screenprinting: Stencils on Screens (1907)

- Flexography: Flexible Printing Plates

- Dot Matrix Printer: Dots Make Pictures (1968)

- Thermal Printer: Heat on Special Paper

- Laser Printer: Fast and High-Quality (1969)

- Inkjet Printer: Tiny Drops of Ink

- Dye-Sublimation Printer: Heat Transfers Dye

- Digital Press: Printing from Digital Files (1993)

- Frescography: Digital Murals (1998)

- 3D Printing: Building Objects Layer by Layer

- Technological Developments in Printing

Stenciling: Early Art and Patterns

Hand stencils are made by blowing paint over a hand pressed against a wall. These have been found in Asia and Europe, dating back over 35,000 years! Stenciling has been used for a long time to paint on all sorts of materials.

Stencils might have been used to color cloth for many years. This technique became very advanced in Japan during the Edo period for making patterns on silk clothes. In Europe, from about 1450 AD, stencils were used to add color to black and white old master prints, especially woodcuts. This was common for playing cards, which continued to be colored by stencil long after other prints were left in black and white. Stencils helped mass-produce items because the designs did not have to be drawn by hand every time.

Brick Stamps: Naming Ancient Buildings

The Akkadian Empire (2334–2154 BCE) in Mesopotamia used brick stamps. They used them to mark bricks used in temples with the ruler's name. For example, a stamp from ruler Naram-Sin might say, "Naram-sin builder, the temple of Goddess Inanna". Not every brick was stamped, just enough to show who built the temple and for which god. Stamps were used because writing on each brick by hand was too slow.

Seals: Ancient Signatures and Symbols

In China, people have used seals since at least the Shang dynasty (2nd millennium BCE). In the Western Zhou period, sets of seal stamps were put into blocks of type. These were used on clay molds to make bronze objects. By the end of the 3rd century BCE, seals were also used to print on pottery. Later, in the Northern dynasties, there are records of wooden seals with up to 120 characters.

Seals also had a religious meaning. Daoists used seals to help heal people by pressing special characters onto their skin. They were also used to stamp food, creating a charm to prevent sickness. The first signs of these practices appeared in a Buddhist setting around the mid-5th century CE. Centuries later, seals were used to create hundreds of Buddha images.

In the West, people used personal or official seals to mark documents. This started in the Roman Empire and continued until the 1800s, when signatures became more common. These seals were often made from a ring with a design.

Chinese seals were usually square or rectangular with a flat base. They had characters carved backward and were used to stamp on paper. This is very similar to how block printing works. Some wooden seals were as big as printing blocks and had over a hundred characters. Western seals, however, were often round or oval, like cylinders or scarabs. They mostly had pictures or designs, and only sometimes writing. The cylindrical seals used to roll over clay could not easily become a printing surface.

Stone, Clay, and Bronze Blocks: Printing on Fabric

People used stone and bronze blocks to print on fabric. Evidence of these has been found in places like Mawangdui in China. Block-printed fabrics have also been discovered in Hubei province.

Pliny the Elder wrote about printing textiles with clay blocks in Egypt in the 1st century CE. We have examples of printed fabrics from Egypt, Rome, and other places dating back to the 4th century CE.

In the 4th century, people in East Asia started making paper rubbings from stone carvings. These carvings included beautiful writing and texts. One of the earliest examples is a stone carving from the early 6th century that was cut in a mirror image, suggesting it was meant for printing.

Woodblock Printing: Books and Art

Woodblock printing (also called xylography) was the first way to print on paper. It became very popular across East Asia for printing on textiles and later on paper, especially with the rise of Buddhism. The oldest examples of woodblock printing on cloth from China are from the Han dynasty (before 220 CE). Ukiyo-e is a famous type of Japanese woodblock art print. In Europe, most uses of this technique on paper are called woodcuts.

The Start of Woodblock Printing in Asia

Inscribed seals made of metal or stone, especially jade, likely gave people the idea for printing. In China, copies of classic texts were carved onto stone tablets and put in public places for scholars to copy. Some old records mention ink rubbings from these tablets, which might have led to early text copying and then printing. A stone carving from the early 6th century, cut in reverse, suggests it might have been a large printing block.

Mahayana Buddhism greatly influenced the rise of printing. Buddhists believed that religious texts were very important because they contained the Buddha's words. Copying these texts was a way to gain good karma. So, Buddhists quickly saw the benefits of printing to make many copies of texts. By the 7th century CE, they were using woodblocks to create special religious documents. These were printed for rituals and not for everyone to read. They were often buried in sacred ground.

The oldest example of this kind of printed material is a small scroll fragment of a Buddhist spell (dhāraṇī) found in a tomb in Xi'an, China. It was printed using woodblock during the Tang dynasty, around 650–670 CE. Another similar piece was found and dated to 690–699. Around this time, a Chinese monk printed one million copies of an image of Puxian Pusa to give to Buddhist followers.

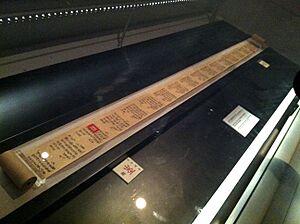

Soon after, evidence of woodblock printing appeared in Korea and Japan. The Great Dharani Sutra was found in South Korea in 1966 and is dated between 704 and 751. It is printed on a long mulberry paper scroll. In Japan, Empress Shōtoku ordered one million copies of a dhāraṇī sutra to be printed around 770 CE. Each copy was stored in a tiny wooden pagoda, and these are known as the Hyakumantō Darani.

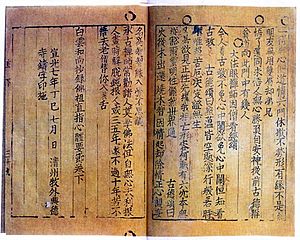

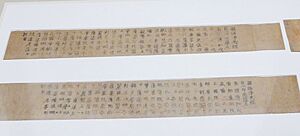

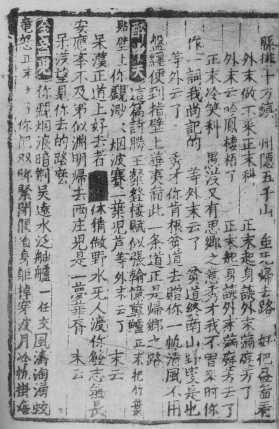

The oldest woodblock prints made for reading were parts of the Lotus Sutra found in Turpan in 1906. They are from the time of Empress Wu Zetian. The oldest text with a specific printing date was found in the Mogao Caves in 1907. This copy of the Diamond Sutra is 14 feet long and says it was made on May 11, 868. It is considered the world's oldest reliably dated woodblock scroll.

During the Song dynasty, schools and government offices used these block prints to share their official versions of classic texts. Other printed works included histories, philosophy, encyclopedias, and books on medicine and war. In 971, work began on a complete Buddhist canon in Chengdu, China. It took 10 years to finish the 130,000 blocks needed to print the text. This finished work, the Kaibao Canon, was printed in 983.

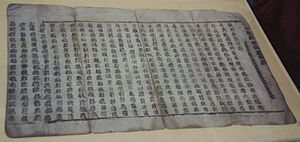

In 989, the Korean King Seongjong of Goryeo asked China for a copy of the complete Buddhist canon. In 1011, King Hyeonjong of Goryeo ordered Korea to carve its own set, known as the Goryeo Daejanggyeong. This huge project was finished in 1087. Sadly, the original woodblocks were destroyed during the Mongol invasion in 1232. King Gojong ordered a new set, which was completed in just 12 years, in 1248. The Goryeo Daejanggyeong has 81,258 printing blocks and is considered the most accurate Buddhist canon in Classical Chinese.

Woodblock Printing in Modern Asia

In Japan, from the Edo period (1600s), books and pictures were mass-produced using woodblock printing. This made them available to many ordinary people. Japan had a very high literacy rate for that time. Almost all samurai could read, and 50-60% of common people could too, thanks to many private schools.

There were over 600 rental bookstores in Edo (now Tokyo). People could borrow woodblock-printed books on many topics, like travel guides, gardening, cookbooks, and novels. Famous best-selling books were reprinted many times.

From the 17th to 19th centuries, ukiyo-e art prints became very popular. These depicted everyday life, kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, beautiful women, and landscapes. Hokusai and Hiroshige are two of the most famous ukiyo-e artists. In the 18th century, Suzuki Harunobu developed multicolor woodblock printing, called nishiki-e. Ukiyo-e art later influenced European art styles like Japonism and Impressionism.

How Woodblock Printing Changed Society

Before printing, private book collections in China grew after paper was invented. Some people owned tens of thousands of scrolls. After woodblock printing became common, official, commercial, and private publishing businesses grew rapidly. The number and size of book collections increased hugely. Private libraries with 10,000 to 20,000 scrolls became common.

Imperial libraries also grew. By the 11th century, government offices saved a lot of money by using printed versions instead of handwritten ones. In 1005, Emperor Zhenzong asked how many woodblocks were at the Directorate of Education. He was told there were over 100,000, compared to fewer than 4,000 at the start of the dynasty. This meant classics and histories were widely available.

Woodblock printing also changed how books looked. Scrolls were slowly replaced by "concertina binding," which folded like an accordion. This made it easier to find specific parts of a text. Later, "butterfly binding" was developed, where two pages were printed on one sheet, then folded inward and glued together. This created a book with alternating printed and blank pages. Eventually, sewn bindings became popular.

The cost of books dropped by about 90% by the end of the 16th century because of woodblock printing. This helped more people learn to read. In 1488, a Korean visitor to China noted that "even village children, ferrymen, and sailors" could read, especially in southern China. However, handwritten manuscripts still existed and were even preferred by some elite scholars as special items.

Woodblock Printing in India and Central Asia

In Buddhism, copying and keeping texts was seen as very important. This led to ways of making many copies of prayers and charms. Stamps were carved to print these prayers on clay tablets from at least the 7th century.

Printing also spread west from China. The Uyghurs in Central Asia used wooden movable type by the 12th-13th centuries. Over a thousand pieces of Uyghur wooden type were found in Dunhuang. Printed texts found in Turfan from around 1300 contained many languages, including Chinese, suggesting Chinese craftsmen might have helped.

It's thought that printing spread further west through the Mongol Empire. Many Uyghurs joined the Mongol army, and their culture was important in the empire. After the Mongols took over Persia, woodblock printing was used there for paper money, just like in China. Paper money was printed in Tabriz in 1294, but people refused to use it. Between 1301 and 1311, a Persian prime minister described Chinese woodblock printing in his writings.

Early Printing in Egypt

About fifty pieces of medieval Arabic block printing, called tarsh, have been found in Egypt. They were printed between 900 and 1300 in black ink on paper. These fragments are religious, used for charms and prayers. Some historians believe they are connected to Chinese printing because they were printed using a similar brush and pad method. However, others argue they were printed using metal plates and did not have a big impact like other Chinese products.

Woodblock Printing in Europe

Woodblock printing was used for fabric patterns in Europe by the mid-14th century and for images on paper by the end of the century. These block prints were made in Germany and Venice between 1400 and 1450. They were mostly religious and were printed as outlines, then colored by hand or with stencils.

There is no strong proof that Chinese printing technology directly spread to Europe. However, some people think it might have, due to communication during the Mongol Empire. They point to similarities between block prints in both areas. For example, European wood blocks were cut along the grain of the wood, like the Chinese method, instead of across it, which was common in Europe. They also used water-based ink and printed only on one side of the paper, using rubbing instead of pressure. Some early European visitors to China noted how cheap and common printing was there.

However, other scholars disagree. They point out that the Mongols' attempt to use printed paper money in Persia failed, and no books were printed in Persia before the 1800s. Also, there's no evidence of Asian movable type or printed books in Europe before 1450. They suggest that similarities might just be because different people came up with similar ideas.

Movable Type: Individual Letters for Printing

Movable type is a printing system where individual pieces of type (like small blocks with letters on them) are used. You can arrange these pieces to form words and sentences.

Ceramic Movable Type

Movable type was invented in China during the Northern Song dynasty around 1041 by a commoner named Bi Sheng. His movable type was made from fired porcelain. After his death, his family kept the ceramic type. Later, in 1193, a Chinese official mentioned movable type and gave credit to Bi Sheng.

However, ceramic type didn't work well with water-based Chinese ink. Also, the size of the type could change when baked, making them uneven. So, it didn't become very popular.

Wooden Movable Type

Bi Sheng also tried making wooden movable type. But it was often uneven after soaking in ink, so ceramic was preferred at first. However, wooden movable type reached the Tangut Western Xia by the 12th century. They printed the Auspicious Tantra of All-Reaching Union, a 449-page book, which is the oldest existing example of a text printed with wooden movable type.

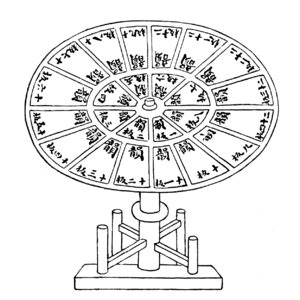

Wang Zhen, who lived in the Yuan dynasty, described wooden movable type in his book Book of Agriculture in 1313. He explained how to make individual characters from wood, cut them into squares, and make sure they were all the same height. Then, they were placed in a form, and bamboo strips and wooden plugs were used to hold them firmly in place for printing.

Wang Zhen used two large rotating tables to organize his type. One table had 24 sections for types based on rhyming patterns, and the other held miscellaneous characters. Using over 30,000 wooden movable types, Wang Zhen printed a hundred copies of his local history book, which had over 60,000 characters. Wooden movable type printing became more common during the Ming dynasty and widespread during the Qing dynasty.

Metal Movable Type

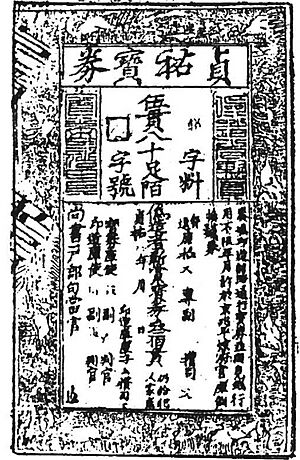

Metal movable type appeared in China during the late Song and Yuan dynasties. Bronze movable types were used to print banknotes and official documents by both the Song and Jin dynasties. For example, a paper banknote from 1215–1216 shows small characters printed with movable copper type to prevent fake money.

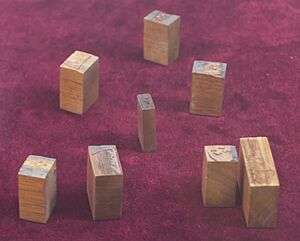

In 1234, cast metal movable type was used in Goryeo (Korea) to print a 50-volume book. No copies of this book still exist. However, the oldest existing book printed with movable metal type is the Jikji from 1377. A French scholar noted that this Korean metal movable type was "extremely similar to Gutenberg's."

Tin movable type was mentioned in a Chinese book from 1298, but it wasn't very good for printing. Bronze movable type only became widely used in China in the late 1400s.

Why Movable Type Didn't Replace Woodblocks in Asia

For the first 300 years after its invention, movable type printing was not used much. Even in Korea, where metal movable type was most common, it never fully replaced woodblock printing. Even the new Korean alphabet, Hangeul, was first printed using woodblocks.

One reason is that making over 200,000 individual pieces of type for Chinese characters was very expensive. Also, for just a few copies of a book, it was cheaper to pay someone to copy it by hand than to use woodblock printing. In Korea, the movable type system was mostly used by the royal family and a small group of elite people. They kept control over this new technology.

In China, movable type was used for less than 10% of all printed materials, while 90% still used woodblock technology. Woodblocks remained the main printing method in China until lithography was introduced in the late 1800s.

Some people used to think that woodblock printing held back printing in East Asia. But modern experts point out that early European visitors to China were amazed by how cheap and common printing was there. One British observer in the late 1800s noted that books in China were incredibly cheap, even though each page was carved by hand. This was because so many copies were sold.

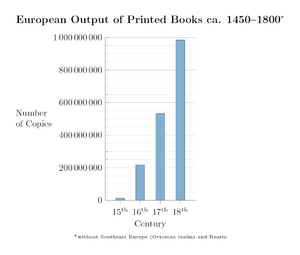

Other scholars say that while China led in book production for a long time, Europe caught up after the mechanical printing press was invented in the mid-1400s.

European Movable Type: Gutenberg's Revolution (1439)

It is generally believed that Johannes Gutenberg from Mainz, Germany, developed European movable type printing with the printing press around 1439. In just over ten years, the European age of printing began. However, the evidence shows it was a more complex process that spread across different places.

Compared to woodblock printing, setting pages with movable type was faster and the metal type pieces lasted longer. The letters were also more uniform, leading to modern typography and fonts. The high quality and relatively low price of the Gutenberg Bible (1455) showed how good movable type was. Printing presses quickly spread across Europe, leading to the Renaissance and then worldwide. Today, almost all movable type printing comes from Gutenberg's invention, which is often called one of the most important inventions of the last thousand years.

Gutenberg also created an oil-based ink that was more durable than older water-based inks. As a skilled goldsmith, he used his knowledge of metals. He was the first to make his type from an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, called type metal. This was key for making strong type that produced high-quality books. To make these lead types, Gutenberg used a special mold that allowed him to create new movable types with great precision very quickly.

The invention of the printing press changed communication and book making forever, helping knowledge spread widely. Printing quickly spread from Germany as German printers moved to other countries and foreign apprentices returned home. A printing press was built in Venice in 1469, and by 1500, the city had 417 printers. Printing presses were set up in Paris (1470), Kraków (1473), and England (1476). The first printing press in the Americas was in Mexico City in 1539, and in Southeast Asia, it was in the Philippines in 1593.

Gutenberg's press was much more efficient than copying by hand. It stayed mostly the same for over 300 years. By 1800, Lord Stanhope built a press entirely from cast iron, which reduced the effort needed by 90% and doubled the printing area. Later, in the early 1800s, German printer Friedrich Koenig designed the first non-manpowered machine, using steam. This steam press could print 250 sheets per hour.

Flat-Bed Printing Press: The Basic Machine

A printing press is a machine that uses pressure to transfer ink from a surface onto paper or cloth. Johannes Gutenberg, a goldsmith, put these systems together in Germany in the mid-15th century. Printing methods based on Gutenberg's press quickly spread across Europe and then the world. They replaced most block printing and became the basis for modern movable type printing. Today, offset printing has largely replaced the printing press for making many copies.

Gutenberg started working on his printing press around 1436. He partnered with Andreas Dritzehen and Andreas Heilmann. A lawsuit against Gutenberg in 1439 provides the first official record of his work, mentioning type, metals like lead, and his type mold.

Other people in Europe were also working on movable type at this time, like Procopius Waldvogel in France and Laurens Janszoon Coster in the Netherlands. However, they are not known to have made specific improvements to the printing press itself.

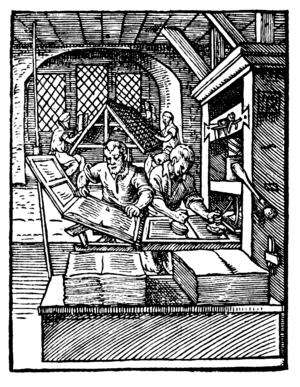

Printing Houses: How Books Were Made

Early printing houses, around Gutenberg's time, were run by "master printers." These printers owned shops, chose and edited books, decided how many copies to print, sold their works, and organized how books were distributed. Some master printing houses became important cultural centers.

- Print shop apprentices: These were young people, usually 15 to 20 years old, who worked for master printers. They didn't need to know how to read. Apprentices prepared ink, dampened paper, and helped with the press. If an apprentice wanted to become a compositor (someone who sets type), they had to learn Latin and work under a journeyman.

- Journeyman printers: After their training, journeyman printers could move between employers. This helped printing spread to new areas.

- Compositors: These were the people who set the type for printing.

- Pressmen: These people operated the printing press, which was hard physical work.

The earliest known picture of a European, Gutenberg-style print shop is from 1499. It shows a compositor setting type and a bookshop next to the printing area.

Paying for Books: New Ways to Publish

By the 16th century, jobs in printing became more specialized. The role of the Master Printer changed, giving way to the bookseller-publisher. Printing became more focused on making money.

From 1500 to 1700, publishers found new ways to fund projects:

- Subscription publishing: This started in England in the early 1600s. A publisher would create a plan for a book and ask potential buyers to sign up for a copy. If not enough people subscribed, the book wouldn't be published. Lists of subscribers were often included in the books as a way to show support.

- Installment publishing: Books were released in parts until the whole book was complete. This helped spread the cost over time and allowed publishers to get money back earlier to cover future production costs.

Publishing trade groups helped publishers work together. They also had ways to control each other, like a cartel, to deal with problems like labor unrest among workers.

Publishers usually bought the copyright for a book from the author. This required a lot of money, in addition to the cost of equipment and staff. Sometimes, an author with money would keep the copyright and just pay the printer to print the book.

Rotary Printing Press: Printing on Rolls

In a rotary printing press, the printing images are carved around a cylinder. This allows printing on long, continuous rolls of paper, cardboard, plastic, or other materials. Josiah Warren invented rotary drum printing in 1832. His design was later improved by Richard March Hoe in 1843 and William Bullock in 1863.

Intaglio Printing: Ink in Grooves

Intaglio is a family of printmaking techniques where the image is cut into a surface, usually a copper or zinc plate. The cuts are made by etching, engraving, or other methods. To print an intaglio plate, the surface is covered in thick ink. Most of the excess ink is wiped away, leaving ink only in the cut-in lines. Then, a damp piece of paper is placed on top, and the plate and paper are run through a printing press. The pressure transfers the ink from the grooves onto the paper.

Lithography: Printing with Chemicals (1796)

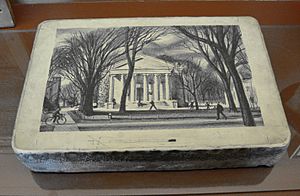

Invented by Aloys Senefelder in 1796, lithography is a printing method that uses chemical processes on a smooth surface. For example, the part of the image that will print attracts ink, while the parts that won't print attract water. When the plate is exposed to ink and water, the ink sticks to the image, and the water cleans the non-image areas. This allows for a relatively flat printing plate, which can be used for many more prints than older methods.

Today, high-volume lithography is used to make posters, maps, books, newspapers, and packaging. Most books and large amounts of text are now printed using offset lithography.

In offset lithography, which uses photography, flexible aluminum, polyester, or paper plates are used instead of stone. Modern printing plates have a rough texture and are covered with a light-sensitive material. A photographic negative of the image is placed on the plate and exposed to ultraviolet light. After developing, the image appears. This image can also be created directly by a laser.

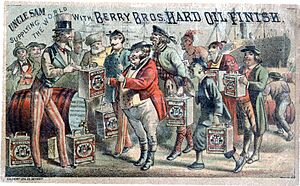

Color Printing: Adding Hues to Prints

According to Michael Sullivan, the earliest known example of color printing is a two-color front page of a Buddhist sutra scroll from 1346. Color printing continued to be used in China throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Chromolithography became the most successful way to print in color in the 19th century. Other methods used several woodblocks for different colors. Hand-coloring also remained important. Chromolithography developed from lithography and involves printing in color. The first technique used multiple lithographic stones, one for each color, which was very expensive for high-quality results. Depending on the number of colors, a chromolithograph could take months to produce by skilled workers.

Cheaper prints could be made by using fewer colors and less detail. For example, advertisements often used an initial black print, then colors were printed over it. For expensive color reproductions, a lithographer would carefully create and correct many stones, sometimes dozens of layers, to match a painting.

Aloys Senefelder, the inventor of lithography, wrote about his plans for color lithography in 1818. Godefroy Engelmann in France received a patent for chromolithography in 1837, though some sources say it was used earlier, for example, in making playing cards.

Offset Press: Indirect Printing (1870s)

Offset printing is a widely used printing technique where the inked image is first transferred from a plate to a rubber blanket, and then from the blanket to the printing surface. When combined with lithography, which uses the idea that oil and water don't mix, the offset technique uses a flat image carrier. The image area attracts ink, while the non-printing area attracts a film of water, keeping it ink-free.

Screenprinting: Stencils on Screens (1907)

Screenprinting started from simple stenciling, especially the Japanese art form called katazome. In this method, artists cut designs into banana leaves and pushed ink through the holes onto textiles. This idea was adopted in France. The modern screenprinting process began with patents by Samuel Simon in England in 1907. This idea was then used in San Francisco by John Pilsworth in 1914 to make multicolor prints.

Flexography: Flexible Printing Plates

Flexography, or "flexo," is a printing method often used for packaging like labels, bags, and boxes.

A flexo print is made by creating a mirrored, 3D raised image on a rubber or polymer material. A measured amount of ink is put onto the printing plate using a special roller. The printing surface then rotates and touches the material being printed, transferring the ink.

At first, flexo printing was basic in quality. High-quality labels were usually printed by offset printing. But now, flexo printing presses have greatly improved. The biggest improvements have been in the photopolymer printing plates themselves, including how they are made.

Dot Matrix Printer: Dots Make Pictures (1968)

A dot matrix printer is a type of computer printer that has a print head moving back and forth across the page. It prints by hitting an ink-soaked cloth ribbon against the paper, similar to a typewriter. However, unlike a typewriter, letters are formed from a pattern of dots. This allows for different fonts and graphics. Because it uses mechanical pressure, these printers can make carbon copies.

Each dot is made by a tiny metal rod, called a "wire" or "pin." This pin is pushed forward by a small electromagnet. The moving part of the printer is called the print head. Most dot matrix printers have a single vertical line of dot-making pins.

The first dot-matrix printers were invented in Japan. In 1968, the Japanese company Epson released the EP-101, the world's first dot-matrix printer. In the same year, OKI introduced the first serial impact dot matrix printer.

Thermal Printer: Heat on Special Paper

A thermal printer creates an image by heating special coated paper, called thermal paper. When the paper passes over the thermal print head, the coating turns black in the heated areas, making the image.

Laser Printer: Fast and High-Quality (1969)

The laser printer, based on a modified xerographic copier, was invented at Xerox in 1969 by researcher Gary Starkweather. He had a working networked printer system by 1971. Laser printing became a huge business for Xerox.

The first commercial laser printer was the IBM 3800 in 1976. It was used for printing large amounts of documents like invoices. While large, it was designed for industrial use, not for individual computers.

The first laser printer for personal computers was released with the Xerox Star 8010 in 1981. It was innovative but very expensive. The first laser printer for the mass market was the HP LaserJet in 1984.

The laser printer played a big role in making desktop publishing popular. This happened with the introduction of the Apple LaserWriter for the Apple Macintosh, along with Aldus PageMaker software, in 1985. With these products, people could create documents that used to require professional typesetting.

Inkjet Printer: Tiny Drops of Ink

Inkjet printers are a type of computer printer that works by spraying tiny droplets of liquid ink onto paper. There are two main types: Continuous and Drop-On-Demand.

Continuous inkjet printers have a continuous stream of ink. Electrically charged droplets are moved by an electric field to print on paper or are collected and reused.

Drop-On-Demand inkjets shoot single drops of ink with each electrical pulse. Hot-melt inks, which printed in full color, were introduced in 1984.

Dye-Sublimation Printer: Heat Transfers Dye

A dye-sublimation printer uses heat to transfer dye to a medium like a plastic card, printer paper, or poster paper. The process usually lays one color at a time using a ribbon with color panels. Most dye-sublimation printers use CMYO colors (Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Clear Overcoating). The clear overcoating protects the print from fading and makes it water-resistant. Many of these printers are used for making photographic prints.

Digital Press: Printing from Digital Files (1993)

Digital printing is the process of reproducing digital images onto a physical surface, such as paper, film, cloth, or plastic.

It is different from older printing methods in several ways:

- Every print can be different, unlike traditional methods that make many copies of the same image from one set of plates.

- The Ink or Toner sits on the surface of the material, rather than soaking in. It is then fused to the surface with heat or UV light.

- It generally creates less waste in terms of chemicals and paper used for setup.

- It is great for making quick test prints or small print runs, making it more accessible and cost-effective for designers.

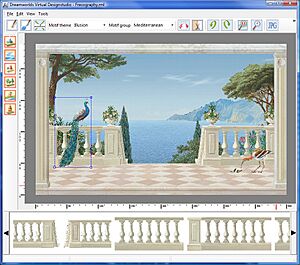

Frescography: Digital Murals (1998)

Frescography is a way to reproduce or create murals using digital printing methods. It was invented in 1998 by Rainer Maria Latzke. Frescography uses digitally cut-out designs stored in a database. Special computer programs allow you to enter the measurements of a wall or ceiling to create a mural design. Architectural parts like beams or windows can be included. Once the design is ready, the images are printed in high resolution on canvas using large printers. The canvas can then be applied to the wall like wallpaper, making it look like a mural painted on site.

3D Printing: Building Objects Layer by Layer

3D printing is a method of turning a virtual 3D model into a physical object. It's a type of rapid prototyping technology. 3D printers usually work by "printing" successive layers on top of each other to build a three-dimensional object. 3D printers are generally faster, more affordable, and easier to use than other similar technologies.

Technological Developments in Printing

Woodcut: Carving for Relief Prints

Woodcut is an artistic technique where an image is carved into a block of wood. The parts that will print are left raised, while the non-printing parts are cut away. The block is cut along the grain of the wood. In Europe, beechwood was common; in Japan, a special type of cherry wood was popular.

Woodcut first appeared in ancient China. From the 6th century, woodcut icons became popular, especially in Chinese Buddhism. Since the 10th century, woodcut pictures were used as illustrations in Chinese books, on banknotes, and as single images.

In Europe, woodcut is the oldest technique for old master prints, starting around 1400. The rise in sales of cheap woodcuts led to lower quality prints. Later, artists like Albrecht Dürer made Western woodcut art very sophisticated.

Engraving: Cutting Designs into Metal

Engraving is the practice of cutting grooves into a hard, flat surface to create a design. This can be done to decorate objects like silver or gold, or to make a printing plate, usually of copper or other metal. These plates are used to print images on paper, which are called engravings. Engraving was historically important for making art prints and illustrations for books and magazines. It has largely been replaced by photography for commercial uses and by etching for art prints.

In ancient times, engraving was seen in shallow grooves on some jewelry. In the European Middle Ages, goldsmiths used engraving to decorate metalwork. They started printing copies of their designs to keep records. From this, they began engraving copper plates to make art prints on paper in Germany in the 1430s. Many early engravers were goldsmiths.

Etching: Using Acid to Create Art

Etching is a process that uses strong acid to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface, creating a design. It is one of the most important techniques for old master prints, along with engraving, and is still widely used today.

Halftoning: Making Pictures with Dots

Halftone is a technique that makes continuous-tone images (like photographs) look like they have different shades by using equally spaced dots of varying sizes. The idea came from William Fox Talbot in the 1850s.

The first successful commercial method was patented by Frederic Ives in Philadelphia in 1881. In 1882, the German George Meisenbach patented a halftone process in England. He used single-lined screens that were turned during exposure to create cross-lined effects. He was the first to have commercial success with halftones.

Xerography: Dry Copying (1938)

Xerography (or electrophotography) is a photocopying technique developed by Chester Carlson in 1938. He received a patent for his invention in 1942. The name "xerography" comes from Greek words meaning "dry writing," because it doesn't use liquid chemicals like older copying methods.

In 1938, a Bulgarian physicist found that some materials, when placed in an electric field and exposed to light, get a permanent electric charge in the exposed areas. This charge stays in the dark and disappears in light. Chester Carlson, an inventor and patent attorney, found making copies of papers painful due to his arthritis. This led him to experiment with photoconductivity.

Carlson made the first "photocopy" in his kitchen in 1938, using a zinc plate covered with sulfur. He wrote "10-22-38 Astoria" on a microscope slide, placed it on the sulfur, and shone a bright light on it. After removing the slide, a mirror image of the words remained. Carlson tried to sell his invention, but companies didn't see a big market for it at the time.

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |