Xerox Star facts for kids

Xerox Star 8010

|

|

| Also known as | Xerox 8010 Information System |

|---|---|

| Developer | Xerox |

| Manufacturer | Xerox |

| Product family | 8000-series |

| Type | Workstation |

| Release date | 1981 |

| Introductory price | US$16,595 (equivalent to $53,000 in 2022) |

| Discontinued | 1985 |

| Operating system | Pilot |

| CPU | AMD Am2900 based |

| Memory | 384 KB, expandable to 1.5 MB |

| Storage | 10, 29, or 40 MB hard drive and 8" floppy drive |

| Display | 17 inch |

| Graphics | 1024×808 pixels @ 38.7 Hz |

| Connectivity | Ethernet |

| Predecessor | Xerox Alto |

| Successor | Xerox Daybreak (ViewPoint; Xerox 6085) |

The Xerox Star workstation, officially called the Xerox 8010 Information System, was a very important computer. It was the first computer sold to the public that had many features we use every day. These features include a screen that shows pictures (bitmap display) and a way to use the computer with pictures and buttons (graphical user interface).

It also had icons, folders, and a mouse to click on things. The Star could connect to other computers using Ethernet networking. It also had file servers, print servers, and email. Xerox Corporation released the Star on April 27, 1981. The name Star mostly referred to the software for offices. Other versions were sold for research and software development.

Contents

History of the Xerox Star

Building on the Xerox Alto

The idea for the Xerox Star came from an experimental computer called the Xerox Alto. The Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) designed the Alto. The first Alto started working in 1972. It was influenced by earlier systems like NLS and PLATO.

Only a few Altos were built at first. By 1979, about 1,000 Altos were used at Xerox. Another 500 were at universities and government offices. The Alto was never meant to be sold to the public.

In 1977, Xerox started a project to turn Alto's ideas into a product. They wanted to create a system for making documents. This system would use expensive laser printing technology. It was aimed at big companies. When the Star system came out in 1981, it was very expensive. A basic system cost about $75,000. Each extra workstation cost about $16,000.

How the Star was Developed

The Star was built at Xerox's Systems Development Department (SDD). This department was set up in 1977. Their goal was to design the "office of the future." They wanted a new system that was easy to use. It also needed to automate many office tasks.

David Liddle led the development team. The team grew to over 200 people. They spent a lot of time planning. This resulted in a very detailed plan called the Red Book. This book guided all the development work. It made sure everything in the computer looked and worked the same way.

The team used the very technologies they were building. They used file sharing, print servers, and email. They were even connected to the Internet, which was then called ARPANET. This helped them communicate between their offices.

The Star was programmed using a language called Mesa. This language was a step towards other programming languages like Modula-2. The Star team also used a special tool for writing software. It helped them keep track of changes to the code.

The software development was very intense. They made many test versions and had people try them out. The engineers had to create new ways for computers to talk to each other. This was because the old ways used in research were not good enough.

The Star also had a version for the Japanese language. This was made with Fuji Xerox. In the end, not all planned features made it into the final product. The focus was on making the computer reliable and fast for its release.

User Interface: How You Used the Star

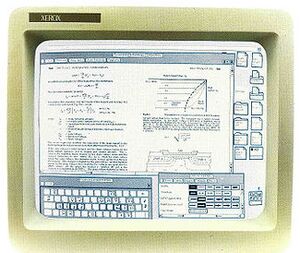

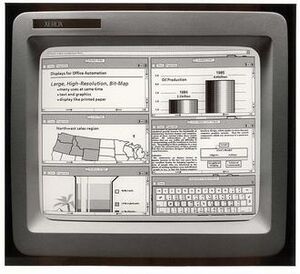

The main idea behind the Star's user interface was to make it like a real office. This made it easy for people to understand. The idea of "what you see is what you get" (WYSIWYG) was very important. Text looked on the screen exactly as it would print. It was black on a white background, just like paper.

One of the main designers, Dr. David Canfield Smith, created the idea of computer icons. He also came up with the desktop metaphor. This meant the user saw a desktop on the screen. It had documents and folders, each with different icons. Clicking an icon would open a window. Users did not start programs first. Instead, they just opened a file. The right program would then appear automatically.

The Star's user interface was based on "objects." For example, a document had page objects, paragraph objects, and character objects. Users would click on an object with the mouse. Then they would press special keys on the keyboard. These keys would do common actions like open, delete, copy, or move. There was also a "Show Properties" key. This key would show settings for the object, like font size for text. These simple rules made all the programs easy to use.

The system was designed so different parts could work together. For example, a chart made in the graphing program could be put into any document. Later, other computers like the Apple Lisa and Macintosh used similar ideas. Microsoft Windows also added this feature with Object Linking and Embedding (OLE) in 1990.

Hardware: What Was Inside the Star

The Star software was designed to run on new types of processors. These processors were called D* (pronounced D-Star) machines. They used a special kind of programming called microcode. This microcode helped the Star software run.

The first machine, called Dolphin, was too expensive. It also wasn't powerful enough for the complex software. It could take over half an hour to restart the system!

The next machine, Dorado, was much faster. It was used for research. But it was too big to be an office computer.

The actual Star workstation hardware was called Dandelion. It was based on a design by Butler Lampson. It used a special kind of processor technology called AMD Am2900 bitslice. An improved version of the Dandelion was called Dandetiger.

The basic Dandelion system had 384 KB of memory. This could be expanded to 1.5 MB. It had a hard drive (10, 29, or 40 MB) and an 8-inch floppy drive. It also came with a mouse and Ethernet connection. This machine cost about $20,000 in 1981. It was as powerful as much more expensive computers of that time. The 17-inch screen was very large for its time. It could show two full pages side by side.

Here are some of the D-Star machines that were sold:

- Dolphin: Xerox 1100 Scientific Information Processor (1979)

- Dorado: Xerox 1132 Lisp machine

- Dandelion: Star, Xerox 1108 Lisp machine (1981)

- Dandetiger: Xerox 1109 Lisp machine

- Daybreak: Xerox 6085 Star successor, Xerox 1186 Lisp machine (1985)

Legacy: The Star's Lasting Impact

Even though the Star itself didn't sell many units, it changed computers forever. Many of its new ideas became common in later computers. These include WYSIWYG editing, Ethernet networking, and network services like printing and file sharing.

The engineers who built the Apple Lisa saw the Star when it was introduced. They went back and changed their computer to use an icon-based system like the Star. Larry Tesler, who worked on Xerox's Gypsy editor, joined Apple in 1980.

Charles Simonyi left Xerox to join Microsoft in 1981. There, he helped create the first WYSIWYG version of Microsoft Word. Later, other people from PARC also joined Microsoft.

The Star, and later versions like Viewpoint, were the first commercial computers to support many different languages. This made them useful for organizations like the Voice of America.

Many products were inspired by the Star's user interface. These include the Apple Lisa, Macintosh, Microsoft Windows, Atari ST, Amiga, and NEXTSTEP. Adobe Systems' PostScript language was based on Xerox's Interpress. Ethernet was also improved and became a standard way for computers to connect.

Some people believe that Apple, Microsoft, and others copied ideas from the Xerox Star. They think Xerox didn't protect its inventions well enough. Xerox did try to get many patents for the Star's new ideas. However, there were rules at the time that limited what Xerox could patent. Also, getting patents for software, especially user interfaces, was a new legal area back then.

Xerox did go to court to protect the Star's user interface. In 1989, Xerox sued Apple. But the lawsuit was dismissed because too much time had passed. In 1994, Apple lost its own lawsuit against Microsoft. This meant Apple no longer had claims to the user interface ideas.

In 2019, a work-in-progress Star emulator called Darkstar was released. This allows people to run the Star software on modern computers.

See also

- Lisp machine

- Pilot (operating system)

| Preceded by Xerox Alto |

Xerox Star 1981-1985 |

Succeeded by Xerox Daybreak |

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |