Banknote facts for kids

A banknote is a special piece of paper that a bank prints. It's a promise to pay the person holding it a certain amount of money. Think of it like an I.O.U. from a bank! Banknotes, along with coins, are the main types of cash we use today. Coins are usually for smaller amounts, while banknotes are for larger amounts.

Long ago, money's value came from the material it was made of, like silver or gold. But carrying lots of heavy metal was hard and risky. So, people started using banknotes instead. These notes were originally a promise to give someone a certain amount of precious metal if they brought the paper back to the bank. This way, people could pay for things using the paper, which represented the gold or silver safely stored in the bank.

Contents

History of Banknotes

Paper money first appeared in China during the Tang Dynasty (around the 7th century). However, the first true paper money, called "jiaozi," didn't become common until the 11th century, during the Song Dynasty. The idea of paper money then spread across the Mongol Empire. European travelers like Marco Polo learned about it in the 13th century and brought the idea back to Europe.

Over time, how people viewed banknotes changed. At first, they were just a promise to pay in precious metals. But eventually, banknotes became valuable on their own, simply because governments said they were money and people trusted them. This type of money is called fiat money.

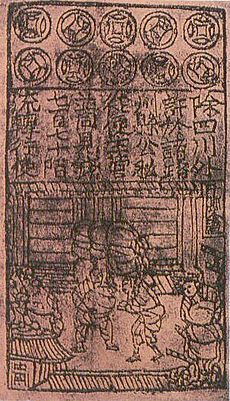

Early Chinese Paper Money

The very first banknote-like papers were used in China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD). Merchants used them as receipts for money they deposited, so they didn't have to carry heavy Chinese coins for big deals. Before these notes, Chinese coins were round with a square hole in the middle, often strung together. For rich merchants, these strings of coins became too heavy for large transactions. To solve this, they left their coins with a trusted person and got a paper receipt showing how much they had. When they returned with the paper, they got their coins back.

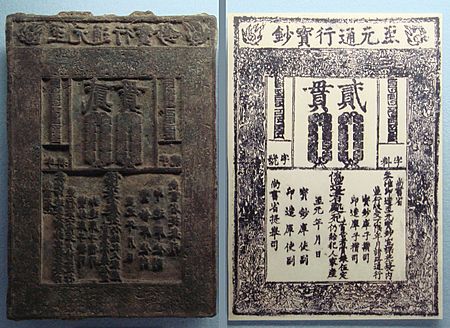

Real paper money, known as "jiaozi," grew from these receipts by the 11th century in the Song Dynasty. By 960 AD, the Song government didn't have enough copper for coins, so they started printing these notes for everyone to use. These notes were a promise from the ruler to exchange them later for something valuable, usually metal coins. The government soon saw how useful printing paper money was. By the early 12th century, they were printing huge amounts of banknotes.

The Song government even set up several factories just for printing paper money. For example, in 1175, the factory in Hangzhou employed over a thousand workers every day! At first, these banknotes were only used in certain areas and for a limited time, usually three years.

However, between 1265 and 1274, the government created a nationwide paper currency that was backed by gold or silver. To prevent people from making fake money, they printed notes with at least six different ink colors, complex designs, and even special fibers in the paper.

The founder of the Yuan dynasty, Kublai Khan, also issued paper money called Jiaochao. Travelers like Marco Polo were very impressed by this, especially because the Chinese government guaranteed the value of the paper money.

European Explorers and Merchants

In the 13th century, European travelers like Marco Polo learned about Chinese paper money. Marco Polo wrote about it in his famous book, The Travels of Marco Polo, explaining how the Great Khan's paper money was accepted everywhere, just like gold or silver coins.

In medieval Italy and Flanders, traders started using promissory notes because it was risky and difficult to carry large amounts of cash over long distances. These notes were like a written order to pay the amount to whoever held the paper. The term "bank note" comes from the Italian "nota di banco," meaning "note of the bank." These early notes gave the holder the right to collect precious metal that was deposited with a banker.

Birth of European Banknotes

The idea of using these receipts as a way to pay for things really took off in the mid-1600s in London. Goldsmiths, who were like early bankers, started giving out receipts that could be paid to anyone who held the document, not just the original person who deposited the gold. This meant the paper note itself became a form of currency, trusted because of the goldsmith's reputation. These goldsmiths also began lending out more money in notes than they actually had in gold, assuming not everyone would ask for their gold back at the same time. These receipts, which were used more and more as money, are considered the first modern banknotes.

The first attempt by a central bank to issue banknotes was in 1661 by Stockholms Banco in Sweden. These notes replaced heavy copper plates used as money. However, this bank printed too much paper money too quickly and went bankrupt just three years later. A new bank was started in 1668, but it didn't issue banknotes again until the 1800s.

Permanent Issue of Banknotes

The idea that money's value comes from a shared agreement in society, rather than just the metal it's made of, helped the permanent use of banknotes begin. An economist named Nicholas Barbon wrote that money "was an imaginary value made by a law for the convenience of exchange."

In 1690, Sir William Phips, the governor of Massachusetts Bay in America, tried issuing paper money to help pay for a war. Other American colonies soon followed, using "bills of credit" to fund military costs and for everyday trading. By the 1760s, these bills were used in most transactions in the colonies.

The first bank to permanently issue banknotes was the Bank of England, created in 1694. It started issuing notes in 1695, promising to pay the holder the note's value on demand. At first, these notes were handwritten for exact amounts. But over time, they started printing standard notes with fixed values, and by 1855, they were printing fully standardized notes that didn't need a specific name or signature.

In the United States, there were early attempts to create a central bank in 1791 and 1816. But it wasn't until 1862 that the US federal government began printing its own banknotes.

Central Bank Control of Money

Originally, a banknote was just a promise to exchange it for metal. But in 1833, a law in England made banknotes "legal tender" during peacetime. This meant they had to be accepted as payment for debts.

Until the mid-1800s, many different commercial banks could print their own banknotes. But in 1844, the Bank Charter Act 1844 gave the Bank of England almost complete control over printing new banknotes, making it the main central bank. This law also said that new banknotes had to be backed by gold or government debt. This gave the Bank of England a monopoly on printing money from 1928 onwards.

How Banknotes Are Destroyed

Banknotes are taken out of circulation when they get old and worn out from being handled every day. Banks use special machines to sort banknotes. These machines check if the notes are real and if they are still good enough to be used. If a note is too worn, dirty, damaged, or torn, it's marked as "unfit."

Unfit notes are sent back to the central bank to be destroyed safely. High-speed machines use a special shredder, like a paper shredder, to cut the banknotes into tiny pieces. This makes it impossible to put them back together like a jigsaw puzzle, especially since pieces from many different notes are mixed together.

After shredding, the tiny paper pieces are often pressed into small blocks. These blocks are then disposed of, sometimes in landfills or by burning. Before the 1990s, unfit banknotes were usually burned, which carried a higher risk of someone trying to tamper with them.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve Banks check all the cash they receive. About one-third of the notes they get are unfit, and these are destroyed. US dollar banknotes usually last more than five years on average. Banknotes that are contaminated (for example, with germs) are also removed from circulation to stop diseases from spreading.

Images for kids

-

Fifty-five dollar bill in 'Continental currency'; leaf design by Benjamin Franklin, 1779

-

Banknotes with a face value of 5000 in different currencies. (United States dollar, CFA franc, Japanese yen, Italian lira, and French franc)

-

Marco Polo described the use of early banknotes in China to Medieval Europe in his book, The Travels of Marco Polo.

-

The sealing of the Bank of England Charter (1694). The Bank began the first permanent issue of banknotes a year later.

-

The Bank of England gained a monopoly over the issue of banknotes with the Bank Charter Act of 1844.

-

When Brazil changed currencies in 1989, the 1000, 5000, and 10,000 cruzados banknotes were overstamped and issued as 1, 5, and 10 cruzados novos banknotes for several months before cruzado novo banknotes were printed and issued. Banknotes can be overstamped with new denominations, typically when a country converts to a new currency at an even, fixed exchange rate (in this case, 1000:1).

-

A former Finnish 10 mark banknote from 1980, depicting President J. K. Paasikivi.

-

Bielefeld Germany 25 Mark 1921. Silk Banknote.

-

Russian American Company-issued Alaskan parchment scrip (c. 1852)

-

Fed Shreds as souvenir from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

-

Shreds of unfit US dollar notes with a typical size of less than 1.5 mm x 16 mm

-

Shredded and briquetted US dollar notes from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (approx. 1000 pieces, 1 kg)

-

Shredded and briquetted euro banknotes from the Deutsche Bundesbank, Germany (approx. 1 kg)

See also

In Spanish: Papel moneda para niños

In Spanish: Papel moneda para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |